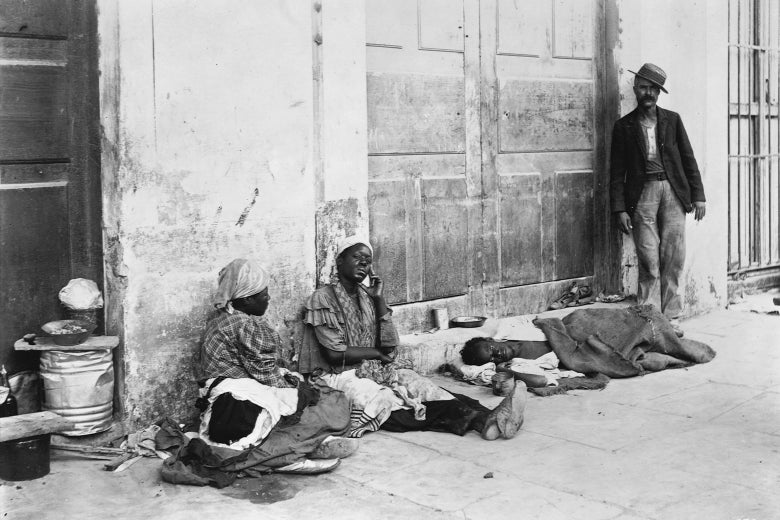

Two children detained by the Border Patrol in a holding cell in Nogales, Ariz. This image has been widely shared on social media in recent days, offered as an example of the Trump administration’s cruel policies toward immigrants, but in fact the picture was taken in 2014.

Devrai-je sacrifier mon enfant premier-né pour payer pour mon crime, le fils, chair de ma chair, pour expier ma faute? On te l’a enseigné, ô homme, ce qui est bien et ce que l’Eternel attend de toi: c’est que tu te conduises avec droiture, que tu prennes plaisir à témoigner de la bonté et qu’avec vigilance tu vives pour ton Dieu. Michée 6: 7-8

Laissez les petits enfants, et ne les empêchez pas de venir à moi; car le royaume des cieux est pour ceux qui leur ressemblent. Jésus (Matthieu 19: 14)

Quiconque reçoit en mon nom un petit enfant comme celui-ci, me reçoit moi-même. Mais, si quelqu’un scandalisait un de ces petits qui croient en moi, il vaudrait mieux pour lui qu’on suspendît à son cou une meule de moulin, et qu’on le jetât au fond de la mer. Jésus (Matthieu 18: 5-6)

Une civilisation est testée sur la manière dont elle traite ses membres les plus faibles. Pearl Buck

Le monde moderne n’est pas mauvais : à certains égards, il est bien trop bon. Il est rempli de vertus féroces et gâchées. Lorsqu’un dispositif religieux est brisé (comme le fut le christianisme pendant la Réforme), ce ne sont pas seulement les vices qui sont libérés. Les vices sont en effet libérés, et ils errent de par le monde en faisant des ravages ; mais les vertus le sont aussi, et elles errent plus férocement encore en faisant des ravages plus terribles. Le monde moderne est saturé des vieilles vertus chrétiennes virant à la folie. G.K. Chesterton

Je crois que le moment décisif en Occident est l’invention de l’hôpital. Les primitifs s’occupent de leurs propres morts. Ce qu’il y a de caractéristique dans l’hôpital c’est bien le fait de s’occuper de tout le monde. C’est l’hôtel-Dieu donc c’est la charité. Et c’est visiblement une invention du Moyen-Age. René Girard

Notre monde est de plus en plus imprégné par cette vérité évangélique de l’innocence des victimes. L’attention qu’on porte aux victimes a commencé au Moyen Age, avec l’invention de l’hôpital. L’Hôtel-Dieu, comme on disait, accueillait toutes les victimes, indépendamment de leur origine. Les sociétés primitives n’étaient pas inhumaines, mais elles n’avaient d’attention que pour leurs membres. Le monde moderne a inventé la « victime inconnue », comme on dirait aujourd’hui le « soldat inconnu ». Le christianisme peut maintenant continuer à s’étendre même sans la loi, car ses grandes percées intellectuelles et morales, notre souci des victimes et notre attention à ne pas nous fabriquer de boucs émissaires, ont fait de nous des chrétiens qui s’ignorent. René Girard

L’inauguration majestueuse de l’ère « post-chrétienne » est une plaisanterie. Nous sommes dans un ultra-christianisme caricatural qui essaie d’échapper à l’orbite judéo-chrétienne en « radicalisant » le souci des victimes dans un sens antichrétien. René Girard

J’espère offrir mon fils unique en martyr, comme son père. Dalal Mouazzi (jeune veuve d’un commandant du Hezbollah mort en 2006 pendant la guerre du Liban, à propos de son gamin de 10 ans)

Nous n’aurons la paix avec les Arabes que lorsqu’ils aimeront leurs enfants plus qu’ils ne nous détestent. Golda Meir

Les Israéliens ne savent pas que le peuple palestinien a progressé dans ses recherches sur la mort. Il a développé une industrie de la mort qu’affectionnent toutes nos femmes, tous nos enfants, tous nos vieillards et tous nos combattants. Ainsi, nous avons formé un bouclier humain grâce aux femmes et aux enfants pour dire à l’ennemi sioniste que nous tenons à la mort autant qu’il tient à la vie. Fathi Hammad (responsable du Hamas, mars 2008)

L’image correspondait à la réalité de la situation, non seulement à Gaza, mais en Cisjordanie. Charles Enderlin (Le Figaro, 27/01/05)

Oh, ils font toujours ça. C’est une question de culture. Représentants de France 2 (cités par Enderlin)

La mort de Mohammed annule, efface celle de l’enfant juif, les mains en l’air devant les SS, dans le Ghetto de Varsovie. Catherine Nay (Europe 1)

Il y a lieu de décider que Patrick Karsenty a exercé de bonne foi son droit à la libre critique (…) En répondant à Denis Jeambar et à Daniel Leconte dans le Figaro du 23 janvier 2005 que « l’image correspondait à la réalité de la situation, non seulement à Gaza, mais en Cisjordanie », alors que la diffusion d’un reportage s’entend comme le témoignage de ce que le journaliste a vu et entendu, Charles Enderlin a reconnu que le film qui a fait le tour du monde en entrainant des violences sans précédent dans toute la région ne correspondait peut-être pas au commentaire qu’il avait donné. Laurence Trébucq (Présidente de la Cour d’appel de Paris, 21.05.08)

Voilà sept ans qu’une campagne obstinée et haineuse s’efforce de salir la dignité professionnelle de notre confrère Charles Enderlin, correspondant de France 2 à Jerusalem. Voilà sept ans que les mêmes individus tentent de présenter comme une « supercherie » et une « série de scènes jouées » , son reportage montrant la mort de Mohammed al-Doura, 12 ans, tué par des tirs venus de la position israélienne, le 30 septembre 2000, dans la bande de Gaza, lors d’un affrontement entre l’armée israélienne et des éléments armés palestiniens. Appel du Nouvel observateur (27 mai 2008)

This is not staging, it’s playing for the camera. When they threw stones and Molotov cocktails, it was in part for the camera. That doesn’t mean it’s not true. They wanted to be filmed throwing stones and being hit by rubber bullets. All of us — the ARD too — did reports on kids confronting the Israeli army, in order to be filmed in Ramallah, in Gaza. That’s not staging, that’s reality. Charles Enderlin

Dans le numéro 1931 du Nouvel Observateur, daté du 8 novembre 2001, Sara Daniel a publié un reportage sur le « crime d’honneur » en Jordanie. Dans son texte, elle révélait qu’à Gaza et dans les territoires occupés, les crimes dits d’honneur qui consistent pour des pères ou des frères à abattre les femmes jugées légères représentaient une part importante des homicides. Le texte publié, en raison d’un défaut de guillemets et de la suppression de deux phrases dans la transmission, laissait penser que son auteur faisait sienne l’accusation selon laquelle il arrivait à des soldats israéliens de commettre un viol en sachant, de plus, que les femmes violées allaient être tuées. Il n’en était évidemment rien et Sara Daniel, actuellement en reportage en Afghanistan, fait savoir qu’elle déplore très vivement cette erreur qui a gravement dénaturé sa pensée. Une mise au point de Sara Daniel (Le Nouvel Observateur, le 15 novembre 2001)

Les Israéliens ne savent pas que le peuple palestinien a progressé dans ses recherches sur la mort. Il a développé une industrie de la mort qu’affectionnent toutes nos femmes, tous nos enfants, tous nos vieillards et tous nos combattants. Ainsi, nous avons formé un bouclier humain grâce aux femmes et aux enfants pour dire à l’ennemi sioniste que nous tenons à la mort autant qu’il tient à la vie. Fathi Hammad (responsable du Hamas, mars 2008)

Les pays européens qui ont transformé la Méditerranée en un cimetière de migrants partagent la responsabilité de chaque réfugié mort. Erdogan

Mr. Kurdi brought his family to Turkey three years ago after fleeing fighting first in Damascus, where he worked as a barber, then in Aleppo, then Kobani. His Facebook page shows pictures of the family in Istanbul crossing the Bosporus and feeding pigeons next to the famous Yeni Cami, or new mosque. From his hospital bed on Wednesday, Mr. Kurdi told a Syrian radio station that he had worked on construction sites for 50 Turkish lira (roughly $17) a day, but it wasn’t enough to live on. He said they depended on his sister, Tima Kurdi, who lived in Canada, for help paying the rent. Ms. Kurdi, speaking Thursday in a Vancouver suburb, said that their father, still in Syria, had suggested Abdullah go to Europe to get his damaged teeth fixed and find a way to help his family leave Turkey. She said she began wiring her brother money three weeks ago, in €1,000 ($1,100) amounts, to help pay for the trip. Shortly after, she said her brother called her and said he wanted to bring his whole family to Europe, as his wife wasn’t able to support their two boys alone in Istanbul. “If we go, we go all of us,” Ms. Kurdi recounted him telling her. She said she spoke to his wife last week, who told her she was scared of the water and couldn’t swim. “I said to her, ‘I cannot push you to go. If you don’t want to go, don’t go,’” she said. “But I guess they all decided they wanted to do it all together.” At the morgue, Mr. Kurdi described what happened after they set off from the deserted beach, under cover of darkness. “We went into the sea for four minutes and then the captain saw that the waves are so high, so he steered the boat and we were hit immediately. He panicked and dived into the sea and fled. I took over and started steering, the waves were so high the boat flipped. I took my wife in my arms and I realized they were all dead.” Mr. Kurdi gave different accounts of what happened next. In one interview, he said he swam ashore and walked to the hospital. In another, he said he was rescued by the coast guard. In Canada, Ms. Kurdi said her brother had sent her a text message around 3 a.m. Turkish time Wednesday confirming they had set off. (…) “He said, ‘I did everything in my power to save them, but I couldn’t,’” she said. “My brother said to me, ‘My kids have to be the wake-up call for the whole world.’” WSJ

Personne ne dit que ce n’est pas raisonnable de partir de Turquie avec deux enfants en bas âge sur une mer agitée dans un frêle esquife. Arno Klarsfeld

La justice israélienne a dit disposer d’une déposition selon laquelle la famille d’un bébé palestinien mort dans des circonstances contestées dans la bande de Gaza avait été payée par le Hamas pour accuser Israël, ce que les parents ont nié. Vif émoi après la mort de l’enfant. Leïla al-Ghandour, âgée de huit mois, est morte mi-mai alors que l’enclave palestinienne était depuis des semaines le théâtre d’une mobilisation massive et d’affrontements entre Palestiniens et soldats israéliens le long de la frontière avec Gaza. Son décès a suscité un vif émoi. Sa famille accuse l’armée israélienne d’avoir provoqué sa mort en employant des lacrymogènes contre les protestataires, parmi lesquels se trouvait la fillette. La fillette souffrait-elle d’un problème cardiaque ? L’armée israélienne, se fondant sur les informations d’un médecin palestinien resté anonyme mais qui selon elle connaissait l’enfant et sa famille, dit que l’enfant souffrait d’un problème cardiaque. Le ministère israélien de la Justice a rendu public jeudi l’acte d’inculpation d’un Gazaoui de 20 ans, présenté comme le cousin de la fillette. Selon le ministère, il a déclaré au cours de ses interrogatoires par les forces israéliennes que les parents de Leila avaient touché 8.000 shekels (1.800 euros) de la part de Yahya Sinouar, le chef du Hamas dans la bande de Gaza, pour dire que leur fille était morte des inhalations de gaz. Une « fabrication » du Hamas dénoncée par Israël. Les parents ont nié ces déclarations, réaffirmé que leur fille était bien morte des inhalations, et ont contesté qu’elle était malade. Selon la famille, Leïla al-Ghandour avait été emmenée près de la frontière par un oncle âgé de 11 ans et avait été prise dans les tirs de lacrymogènes. Europe 1

Donald Trump aurait (…) menti en affirmant que la criminalité augmentait en Allemagne, en raison de l’entrée dans le pays de 1,1 million de clandestins en 2015. (…) Les articles se sont immédiatement multipliés pour dénoncer « le mensonge » du président américain. Pourquoi ? Parce que les autorités allemandes se sont félicitées d’une baisse des agressions violentes en 2017. C’est vrai, elles ont chuté de 5,1% par rapport à 2016. Est-il possible, cependant, de feindre à ce point l’incompréhension ? Car les détracteurs zélés du président omettent de préciser que la criminalité a bien augmenté en Allemagne à la suite de cette vague migratoire exceptionnelle : 10% de crimes violents en plus, sur les années 2015 et 2016. L’étude réalisée par le gouvernement allemand et publiée en janvier dernier concluait même que 90% de cette augmentation était due aux jeunes hommes clandestins fraîchement accueillis, âgés de 14 à 30 ans. L’augmentation de la criminalité fut donc indiscutablement liée à l’accueil de 1,1 millions de clandestins pendant l’année 2015. C’est évidement ce qu’entend démontrer Donald Trump. Et ce n’est pas tout. Les chiffres du ministère allemand de l’Intérieur pour 2016 révèlent également une implication des étrangers et des clandestins supérieure à celle des Allemands dans le domaine de la criminalité. Et en hausse. La proportion d’étrangers parmi les personnes suspectées d’actes criminels était de 28,7% en 2014, elle est passée à 40,4% en 2016, avant de chuter à 35% en 2017 (ce qui reste plus important qu’en 2014). En 2016, les étrangers étaient 3,5 fois plus impliqués dans des crimes que les Allemands, les clandestins 7 fois plus. Des chiffres encore plus élevés dans le domaine des crimes violents (5 fois plus élevés chez les étrangers, 15 fois chez les clandestins) ou dans celui des viols en réunion (10 fois plus chez les étrangers, 42 fois chez les clandestins !). Factuellement, la criminalité n’augmente pas aujourd’hui en Allemagne. Mais l’exceptionnelle vague migratoire voulue par Angela Merkel en 2015 a bien eu pour conséquence l’augmentation de la criminalité en Allemagne. Les Allemands, eux, semblent l’avoir très bien compris. Valeurs actuelles

Je vous demande de ne rien céder, dans ces temps troublés que nous vivons, de votre amour pour l’Europe. Je vous le dis avec beaucoup de gravité. Beaucoup la détestent, mais ils la détestent depuis longtemps et vous les voyez monter, comme une lèpre, un peu partout en Europe, dans des pays où nous pensions que c’était impossible de la voir réapparaître. Et des amis voisins, ils disent le pire et nous nous y habituons. Emmanuel Macron

Il y a des choses insoutenables. Mais pourquoi on en est arrivé là ? Parce que justement il y a des gens comme Emmanuel Macron qui venaient donner des leçons de morale aux autres. Il y a une inquiétude identitaire » en Europe, « c’est une réalité politique. Tous les donneurs de leçon ont tué l’Europe, il y a une angoisse chez les Européens d’être dilués, pas une angoisse raciste, mais une angoisse de ne plus pouvoir être eux, chez eux. Jean-Sébastien Ferjou

Our message absolutely is don’t send your children unaccompanied, on trains or through a bunch of smugglers. We don’t even know how many of these kids don’t make it, and may have been waylaid into sex trafficking or killed because they fell off a train. Do not send your children to the borders. If they do make it, they’ll get sent back. More importantly, they may not make it. Obama (2014)

I also think that we have to understand the difficulty that President Obama finds himself in because there are laws that impose certain obligations on him. And it was my understanding that the numbers have been moderating in part as the Department of Homeland Security and other law enforcement officials understood that separating children from families — I mean, the horror of a father or a mother going to work and being picked up and immediately whisked away and children coming home from school to an empty house and nobody can say where their mother or father is, that is just not who we are as Americans. And so, I do think that while we continue to make the case which you know is very controversial in some corridors, that we have to reform our immigration system and we needed to do it yesterday. That’s why I approved of the bill that was passed in the Senate. We need to show humanity with respect to people to people who are working, contributing right now. And deporting them, leaving their children alone or deporting an adolescent, doing anything that is so contrary to our core values, just makes no sense. So I would be very open to trying to figure out ways to change the law, even if we don’t get to comprehensive immigration reform to provide more leeway and more discretion for the executive branch. (…) the numbers are increasing dramatically. And the main reason I believe why that’s happening is that the violence in certain of those Central American countries is increasing dramatically. And there is not sufficient law enforcement or will on the part of the governments of those countries to try to deal with this exponential increase in violence, drug trafficking, the drug cartels, and many children are fleeing from that violence. (…) first of all, we have to provide the best emergency care we can provide. We have children 5 and 6 years old who have come up from Central America. We need to do more to provide border security in southern Mexico. (…) they should be sent back as soon as it can be determined who responsible adults in their families are, because there are concerns whether all of them should be sent back. But I think all of them who can be should be reunited with their families. (…) But we have so to send a clear message, just because your child gets across the border, that doesn’t mean the child gets to stay. So, we don’t want to send a message that is contrary to our laws or will encourage more children to make that dangerous journey. Hillary Clinton (2014)

Over the past six years, President Obama has tried to make children the centerpiece of his efforts to put a gentler face on U.S. immigration policy. Even as his administration has deported a record number of unauthorized immigrants, surpassing two million deportations last year, it has pushed for greater leniency toward undocumented children. After trying and failing to pass the Dream Act legislation, which would offer a path to permanent residency for immigrants who arrived before the age of 16, the president announced an executive action in 2012 to block their deportation. Last November, Obama added another executive action to extend similar protections to undocumented parents. “We’re going to keep focusing enforcement resources on actual threats to our security,” he said in a speech on Nov. 20. “Felons, not families. Criminals, not children. Gang members, not a mom who’s working hard to provide for her kids.” But the president’s new policies apply only to immigrants who have been in the United States for more than five years; they do nothing to address the emerging crisis on the border today. Since the economic collapse of 2008, the number of undocumented immigrants coming from Mexico has plunged, while a surge of violence in Central America has brought a wave of migrants from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. According to recent statistics from the Department of Homeland Security, the number of refugees fleeing Central America has doubled in the past year alone — with more than 61,000 “family units” crossing the U.S. border, as well as 51,000 unaccompanied children. For the first time, more people are coming to the United States from those countries than from Mexico, and they are coming not just for opportunity but for survival. The explosion of violence in Central America is often described in the language of war, cartels, extortion and gangs, but none of these capture the chaos overwhelming the region. Four of the five highest murder rates in the world are in Central American nations. The collapse of these countries is among the greatest humanitarian disasters of our time. While criminal organizations like the 18th Street Gang and Mara Salvatrucha exist as street gangs in the United States, in large parts of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador they are so powerful and pervasive that they have supplanted the government altogether. People who run afoul of these gangs — which routinely demand money on threat of death and sometimes kidnap young boys to serve as soldiers and young girls as sexual slaves — may have no recourse to the law and no better option than to flee. The American immigration system defines a special pathway for refugees. To qualify, most applicants must present themselves to federal authorities, pass a “credible fear interview” to demonstrate a possible basis for asylum and proceed through a “merits hearing” before an immigration judge. Traditionally, those who have completed the first two stages are permitted to live with family and friends in the United States while they await their final hearing, which can be months or years later. If authorities believe an applicant may not appear for that court date, they can require a bond payment as guarantee or place the refugee in a monitoring system that may include a tracking bracelet. In the most extreme cases, a judge may deny bond and keep the refugee in a detention facility until the merits hearing. The rules are somewhat different when children are involved. Under the terms of a 1997 settlement in the case of Flores v. Meese, children who enter the country without their parents must be granted a “general policy favoring release” to the custody of relatives or a foster program. When there is cause to detain a child, he or she must be housed in the least restrictive environment possible, kept away from unrelated adults and provided access to medical care, exercise and adequate education. Whether these protections apply to children traveling with their parents has been a matter of dispute. The Flores settlement refers to “all minors who are detained” by the Immigration and Naturalization Service and its “agents, employees, contractors and/or successors in office.” When the I.N.S. dissolved into the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, its detention program shifted to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. Federal judges have ruled that ICE is required to honor the Flores protections for all children in its custody. Even so, in 2005, the administration of George W. Bush decided to deny the Flores protections to refugee children traveling with their parents. Instead of a “general policy favoring release,” the administration began to incarcerate hundreds of those families for months at a time. To house them, officials opened the T. Don Hutto Family Detention Center near Austin, Tex. Within a year, the administration faced a lawsuit over the facility’s conditions. Legal filings describe young children forced to wear prison jumpsuits, to live in dormitory housing, to use toilets exposed to public view and to sleep with the lights on, even while being denied access to appropriate schooling. In a pretrial hearing, a federal judge in Texas blasted the administration for denying these children the protections of the Flores settlement. “The court finds it inexplicable that defendants have spent untold amounts of time, effort and taxpayer dollars to establish the Hutto family-detention program, knowing all the while that Flores is still in effect,” the judge wrote. The Bush administration settled the suit with a promise to improve the conditions at Hutto but continued to deny that children in family detention were entitled to the Flores protections. In 2009, the Obama administration reversed course, abolishing family detention at Hutto and leaving only a small facility in Pennsylvania to house refugee families in exceptional circumstances. For all other refugee families, the administration returned to a policy of release to await trial. Studies have shown that nearly all detainees who are released from custody with some form of monitoring will appear for their court date. But when the number of refugees from Central America spiked last summer, the administration abruptly announced plans to resume family detention. (…) From the beginning, officials were clear that the purpose of the new facility in Artesia was not so much to review asylum petitions as to process deportation orders. “We have already added resources to expedite the removal, without a hearing before an immigration judge, of adults who come from these three countries without children,” the secretary of Homeland Security, Jeh Johnson, told a Senate committee in July. “Then there are adults who brought their children with them. Again, our message to this group is simple: We will send you back.” Elected officials in Artesia say that Johnson made a similar pledge during a visit to the detention camp in July. “He said, ‘As soon as we get them, we’ll ship them back,’ ” a city councilor from Artesia named Jose Luis Aguilar recalled. The mayor of the city, Phillip Burch, added, “His comment to us was that this would be a ‘rapid deportation process.’ Those were his exact words.” (…) “I arrived on July 5 and turned myself in at 2 a.m.,” a 28-year-old mother of two named Ana recalled. In Honduras, Ana ran a small business selling trinkets and served on the P.T.A. of her daughter’s school. “I lived well,” she said — until the gangs began to pound on her door, demanding extortion payments. Within days, they had escalated their threats, approaching Ana brazenly on the street. “One day, coming home from my daughter’s school, they walked up to me and put a gun to my head,” she said. “They told me that if I didn’t give them the money in less than 24 hours, they would kill me.” Ana had already seen friends raped and murdered by the gang, so she packed her belongings that night and began the 1,800-mile journey to the U.S. border with her 7-year-old daughter. Four weeks later, in McAllen, Tex., they surrendered as refugees. Ana and her daughter entered Artesia in mid-July. In October they were still there. Ana’s daughter was sick and losing weight rapidly under the strain of incarceration. Their lawyer, a leader in Chicago’s Mormon Church named Rebecca van Uitert, said that Ana’s daughter became so weak and emaciated that doctors threatened drastic measures. “They were like, ‘You’ve got to force her to eat, and if you don’t, we’re going to put a PICC line in her and force-feed her,’ ” van Uitert said. Ana said that when her daughter heard the doctor say this, “She started to cry and cry.” (…) Many of the volunteers in Artesia tell similar stories about the misery of life in the facility. “I thought I was pretty tough,” said Allegra Love, who spent the previous summer working on the border between Mexico and Guatemala. “I mean, I had seen kids in all manner of suffering, but this was a really different thing. It’s a jail, and the women and children are being led around by guards. There’s this look that the kids have in their eyes. This lackadaisical look. They’re just sitting there, staring off, and they’re wasting away. That was what shocked me most.” The detainees reported sleeping eight to a room, in violation of the Flores settlement, with little exercise or stimulation for the children. Many were under the age of 6 and had been raised on a diet of tortillas, rice and chicken bits. In Artesia, the institutional cafeteria foods were as unfamiliar as the penal atmosphere, and to their parents’ horror, many of the children refused to eat. “Gaunt kids, moms crying, they’re losing hair, up all night,” an attorney named Maria Andrade recalled. Another, Lisa Johnson-Firth, said: “I saw children who were malnourished and were not adapting. One 7-year-old just lay in his mother’s arms while she bottle-fed him.” Mary O’Leary, who made three trips to Artesia last fall, said: “I was trying to talk to one client about her case, and just a few feet away at another table there was this lady with a toddler between 2 and 4 years old, just lying limp. This was a sick kid, and just with this horrible racking cough.” (…) Attorneys for the Obama administration have argued in court, like the Bush administration previously, that the protections guaranteed by the Flores settlement do not apply to children in family detention. “The Flores settlement comes into play with unaccompanied minors,” a lawyer for the Department of Homeland Security named Karen Donoso Stevens insisted to a judge on Aug. 4. “That argument is moot here, because the juvenile is detained — is accompanied and detained — with his mother.” Federal judges have consistently rejected this position. Just as the judge reviewing family detention in 2007 called the denial of Flores protections “inexplicable,” the judge presiding over the Aug. 4 hearing issued a ruling in September that Homeland Security officials in Artesia must honor the Flores Settlement Agreement. “The language of the F.S.A. is unambiguous,” Judge Roxanne Hladylowycz wrote. “The F.S.A. was designed to create a nationwide policy for the detention of all minors, not only those who are unaccompanied.” Olavarria said she was not aware of that ruling and would not comment on whether the Department of Homeland Security believes that the Flores ruling applies to children in family detention today. (…) As the pro bono project in Artesia continued into fall, its attorneys continued to win in court. By mid-November, more than 400 of the detained women and children were free on bond. Then on Nov. 20, the administration suddenly announced plans to transfer the Artesia detainees to the ICE detention camp in Karnes, Tex., where they would fall under a new immigration court district with a new slate of judges. That announcement came at the very moment the president was delivering a live address on the new protections available to established immigrant families. In an email to notify Artesia volunteers about the transfer, an organizer for AILA named Stephen Manning wrote, “The disconnect from the compassionate-ish words of the president and his crushing policies toward these refugees is shocking.” Brown was listening to the speech in her car, while driving to Denver for a rare weekend at home, when her cellphone buzzed with the news that 20 of her clients would be transferred to Texas the next morning. Many of them were close to a bond release; in San Antonio, they might be detained for weeks or months longer. Brown pulled her car to the side of the highway and spent three hours arguing to delay the transfer. Over the next two weeks, officials moved forward with the plan. By mid-December, most of the Artesia detainees were in Karnes (…) One of McPhaul’s colleagues, Judge Gary Burkholder, was averaging a 91.6 percent denial rate for the asylum claims. Some Karnes detainees had been in the facility for nearly six months and could remain there another six. (…) “I agree,” Sischo said. “We should not be spending resources on detaining these families. They should be released. But people don’t understand the law. They think they should be deported because they’re ‘illegals.’ So they’re missing a very big part of the story, which is that they aren’t breaking the law. They’re trying to go through the process that’s laid out in our laws.” Wil S. Hylton (NYT magazine, 2015)

It was the kind of story destined to take a dark turn through the conservative news media and grab President Trump’s attention: A vast horde of migrants was making its way through Mexico toward the United States, and no one was stopping them. “Mysterious group deploys ‘caravan’ of illegal aliens headed for U.S. border,” warned Frontpage Mag, a site run by David Horowitz, a conservative commentator. The Gateway Pundit, a website that was most recently in the news for spreading conspiracies about the school shooting in Parkland, Fla., suggested the real reason the migrants were trying to enter the United States was to collect social welfare benefits. And as the president often does when immigration is at issue, he saw a reason for Americans to be afraid. “Getting more dangerous. ‘Caravans’ coming,” a Twitter post from Mr. Trump read. The story of “the caravan” followed an arc similar to many events — whether real, embellished or entirely imagined — involving refugees and migrants that have roused intense suspicion and outrage on the right. The coverage tends to play on the fears that hiding among mass groups of immigrants are many criminals, vectors of disease and agents of terror. And often the president, who announced his candidacy by blaming Mexico for sending rapists and drug dealers into the United States, acts as an accelerant to the hysteria. The sensationalization of this story and others like it seems to serve a common purpose for Mr. Trump and other immigration hard-liners: to highlight the twin dangers of freely roving migrants — especially those from Muslim countries — and lax immigration laws that grant them easy entry into Western nations. The narrative on the right this week, for example, mostly omitted that many people in the caravan planned to resettle in Mexico, not the United States. And it ignored how many of those who did intend to come here would probably go through the legal process of requesting asylum at a border checkpoint — something miles of new wall and battalions of additional border patrol would not have stopped. (…) The story of the caravan has been similarly exaggerated. And the emotional outpouring from the right has been raw — that was the case on Fox this week when the TV host Tucker Carlson shouted “You hate America!” at an immigrants rights activist after he defended the people marching through Mexico. The facts of the caravan are not as straightforward as Mr. Trump or many conservative pundits have portrayed them. The story initially gained widespread attention after BuzzFeed News reported last week that more than 1,000 Central American migrants, mostly from Honduras, were making their way north toward the United States border. Yet the BuzzFeed article and other coverage pointed out that many in the group were planning to stay in Mexico. That did not stop Mr. Trump from expressing dismay on Tuesday with a situation “where you have thousands of people that decide to just walk into our country, and we don’t have any laws that can protect it.” The use of disinformation in immigration debates is hardly unique to the United States. Misleading crime statistics, speculation about sinister plots to undermine national sovereignty and Russian propaganda have all played a role in stirring up anti-immigrant sentiment in places like Britain, Germany and Hungary. Some of the more fantastical theories have involved a socialist conspiracy to import left-leaning voters and a scheme by the Hungarian-born Jewish philanthropist George Soros to create a borderless Europe. NYT

With the help of a humanitarian group called “Pueblo Sin Fronteras” (people without borders), the 1,000 plus migrants will reach the U.S. border with a list of demands to several governments in Central America, the United States, and Mexico. Here’s what they demanded of Mexico and the United States in a Facebook post: -That they respect our rights as refugees and our right to dignified work to be able to support our families -That they open the borders to us because we are as much citizens as the people of the countries where we are and/or travel -That deportations, which destroy families, come to an end -No more abuses against us as migrants -Dignity and justice -That the US government not end TPS for those who need it -That the US government stop massive funding for the Mexican government to detain Central American migrants and refugees and to deport them -That these governments respect our rights under international law, including the right to free expression -That the conventions on refugee rights not be empty rhetoric. The Blaze

La photographie du 12 juin de la petite Hondurienne de 2 ans est devenue le symbole le plus visible du débat sur l’immigration actuellement en cours aux Etats-Unis et il y a une raison pour cela. Dans le cadre de la politique appliquée par l’administration, avant son revirement de cette semaine, ceux qui traversaient la frontière illégalement étaient l’objet de poursuites criminelles, qui entraînaient à leur tour la séparation des enfants et des parents. Notre couverture et notre reportage saisissent les enjeux de ce moment. Edward Felsenthal (rédacteur en chef de Time)

La version originale de cet article a fait une fausse affirmation quant au sort de la petite fille après la photographie. Elle n’a pas été emmenée en larmes par les patrouilles frontalières ; sa mère l’a récupérée et les deux ont été interpellées ensemble. Time

Cette enfant n’a pas été séparée de ses parents. Sa photo reste un symbole. L’Obs

De nombreuses photos et vidéos circulent sur internet depuis que Donald Trump a mis en place sa politique de tolérance zéro face à l’immigration illégale, ce qui a mené plus de 2.300 enfants à être séparés de leurs parents à la frontière entre Etats-Unis et Mexique. Mais beaucoup d’entre elles ne correspondent pas à la réalité. Vendredi, après la publication d’un décret du président américain marquant son revirement vis-à-vis de cette politique, le doute demeurait sur le temps que mettront ces mineurs à retrouver leurs familles. (…) Au moins trois images, largement partagées sur les réseaux sociaux ces derniers jours, illustrent des situations qui ne sont pas celles vécues par les 2.342 enfants détenus en raison de leur statut migratoire irrégulier. La première montre une fillette hondurienne, Yanela Varela, en larmes. Elle est vite devenue sur Twitter ou Facebook un symbole de la douleur provoquée par la séparation des familles. (…) La photo a été prise le 12 juin dans la ville de McAllen, au Texas, par John Moore, un photographe qui a obtenu le prix Pulitzer et travaille pour l’agence Getty Images. Time Magazine en a fait sa Une, mettant face à face, dans un photomontage sur fond rouge, la petite fille apeurée et un Donald Trump faisant presque trois fois sa taille et la toisant avec cette simple légende: « Bienvenue en Amérique ». Un article en ligne publié par Time et portant sur cette photo affirmait initialement que la petite fille avait été séparée de sa mère. Mais l’article a ensuite été corrigé, la nouvelle version déclarant: « La petite fille n’a pas été emmenée en larmes par des agents de la police frontalière des Etats-Unis, sa mère est venue la chercher et elles ont été emmenées ensemble ». Time a néanmoins utilisé la photo de la fillette pour sa spectaculaire couverture. Mais au Honduras, la responsable de la Direction de protection des migrants au ministère des Affaires étrangères, Lisa Medrano, a donné à l’AFP une toute autre version: « La fillette, qui va avoir deux ans, n’a pas été séparée » de ses parents. Le père de l’enfant, Denis Varela, a confirmé au Washington Post que sa femme Sandra Sanchez, 32 ans, n’avait pas été séparée de Yanela et que les deux étaient actuellement retenues dans un centre pour migrants de McAllen (Texas). Attaqué pour sa couverture, qui a été largement jugée trompeuse, y compris par la Maison Blanche, Time a déclaré qu’il maintenait sa décision de la publier. (…) Un autre cliché montre une vingtaine d’enfants derrière une grille, certains d’entre eux tentant d’y grimper. Il circule depuis des jours comme une supposée photo de centres de détention pour mineurs à la frontière mexicaine. Mais son auteur, Abed Al Ashlamoun, photographe de l’agence EPA, a pris cette image en août 2010 et elle représente des enfants palestiniens attendant la distribution de nourriture pendant le ramadan à Hébron, en Cisjordanie. Enfin, une troisième image est celle d’un enfant en train de pleurer dans ce qui semble être une cage, et qui remporte un grand succès sur Twitter, où elle a été partagée au moins 25.000 fois sur le compte @joseiswriting. Encore une fois, il s’agit d’un trompe-l’oeil: il s’agit d’un extrait d’une photo qui mettait en scène des arrestations d’enfants lors d’une manifestation contre la politique migratoire américaine et publiée le 11 juin dernier sur le compte Facebook Brown Berets de Cemanahuac. La Croix

Au moins 150 migrants centraméricains sont arrivés à Tijuana au Mexique, à la frontière avec les États-Unis. Ils sont décidés à demander l’asile à Washington. Plusieurs centaines de migrants originaires d’Amérique centrale se sont rassemblés dimanche 30 avril à la frontière mexico-américaine au terme d’un mois de traversée du Mexique. Nombre d’entre eux ont décidé de se présenter aux autorités américaines pour déposer des demandes d’asile et devraient être placés en centres de rétention. « Nous espérons que le gouvernement des États-Unis nous ouvrira les portes », a déclaré Reyna Isabel Rodríguez, 52 ans, venu du Salvador avec ses deux petits-enfants. L’ONG Peuple Sans Frontières organise ce type de caravane depuis 2010 pour dénoncer le sort de celles et ceux qui traversent le Mexique en proie à de nombreux dangers, entre des cartels de la drogue qui les kidnappent ou les tuent, et des autorités qui les rançonnent. « Nous voulons dire au président des États-Unis que nous ne sommes pas des criminels, nous ne sommes pas des terroristes, qu’il nous donne la chance de vivre sans peur. Je sais que Dieu va toucher son cœur », a déclaré l’une des organisatrices de la caravane, Irineo Mujica. L’ONG, composée de volontaires, permet notamment aux migrants de rester groupés – lors d’un périple qui se fait à pied, en bus ou en train – afin de se prémunir de tous les dangers qui jalonnent leur chemin. En espagnol, ces caravanes sont d’ailleurs appelées « Via Crucis Migrantes » ou le « Chemin de croix des migrants », en référence aux processions catholiques, particulièrement appréciées en Amérique du Sud, qui mettent en scène la Passion du Christ, ou les derniers événements qui ont précédé et accompagné la mort de Jésus de Nazareth. Cette année, le groupe est parti le 25 mars de Tapachula, à la frontière du Guatemala, avec un groupe de près de 1 200 personnes, à 80 % originaires du Honduras, les autres venant du Guatemala, du Salvador et du Nicaragua, selon Rodrigo Abeja. Dans le groupe, près de 300 enfants âgés de 1 mois à 11 ans, une vingtaine de jeunes homosexuels et environ 400 femmes. Certains se sont ensuite dispersés, préférant rester au Mexique, d’autres choisissant de voyager par leurs propres moyens. En avril, les images de la caravane de migrants se dirigeant vers les États-Unis avaient suscité la colère de Donald Trump et une forte tension entre Washington et Mexico. Le président américain, dont l’un des principaux thèmes de campagne était la construction d’un mur à la frontière avec le Mexique pour lutter contre l’immigration clandestine, avait ordonné le déploiement sur la frontière de troupes de la Garde nationale. Il avait aussi soumis la conclusion d’un nouvel accord de libre-échange en Amérique du Nord à un renforcement des contrôles migratoires par le Mexique, une condition rejetée par le président mexicain Enrique Pena Nieto. France 24

Il faut noter que les migrants qui veulent demander l’asile se rendent facilement aux agents de patrouille aux frontières. Ce ne sont pas des migrants sans papiers classiques, ils viennent avec autant de documents que possible pour obtenir l’asile politique. Dans ce groupe se trouvaient une vingtaine de femmes et d’enfants. La plupart venaient du Honduras. (…) J’avais remarqué une mère qui tenait un enfant. Elle m’a dit que sa fille et elle voyageaient depuis un mois, au départ du Honduras. Elle m’a dit que sa fille avait 2 ans, et j’ai pu voir dans ses yeux qu’elle était sur ses gardes, exténuée et qu’elle avait probablement vécu un voyage très difficile. C’est l’une des dernières familles à avoir été embarquée dans le véhicule. Un des officiers a demandé à la mère de déposer son enfant à terre pendant qu’elle était fouillée. Juste à ce moment-là, la petite fille a commencé à pleurer, très fort. J’ai trois enfants moi-même, dont un tout petit, et c’était très difficile à voir, mais j’avais une fenêtre de tir très réduite pour photographier la scène. Dès que la fouille s’est terminée, elle a pu reprendre son enfant dans ses bras et ses pleurs se sont éteints. Moi, j’ai dû m’arrêter, reprendre mes esprits et respirer profondément. J’avais déjà photographié des scènes comme ça à de nombreuses reprises. Mais celle-ci était unique, d’une part à cause des pleurs de cette enfant, mais aussi parce que cette fois, je savais qu’à la prochaine étape de leur voyage, dans ce centre de rétention, elles allaient être séparées. Je doute que ces familles aient eu la moindre idée de ce qui allait leur arriver. Tous voyageaient depuis des semaines, ils ne regardaient pas la télévision et n’avaient aucun moyen d’être au courant de la nouvelle mesure de tolérance zéro et de séparation des familles mise en place par Trump. (…) Cela fait dix ans que je photographie l’immigration à la frontière américaine, toujours avec l’objectif d’humaniser des histoires complexes. Souvent, on parle de l’immigration avec des statistiques, arides et froides. Et je crois que la seule manière que les personnes dans ce pays trouvent des solutions humaines est qu’elles voient les gens comme des êtres humains. Je n’avais jamais imaginé que j’allais un jour mettre un visage sur une politique de séparation des familles, mais c’est le cas aujourd’hui. John Moore

Pourquoi aurait-elle fait subir ça à notre petite fille ? (….) Je pense que c’était irresponsable de sa part de partir avec le bébé dans les bras parce qu’on ne sait pas ce qui aurait pu arriver. Denis Hernandez

Interrogé par le Daily Mail, Denis Varela a indiqué que sa femme voulait expérimenter le rêve américain et trouver un travail au pays de l’Oncle Sam, mais qu’il était opposé à l’idée qu’elle parte avec sa fille : « Elle est partie sans prévenir. Je n’ai pas pu dire « Au revoir » à ma fille et maintenant la seule chose que je peux faire, c’est attendre. » Le couple a aussi trois autres enfants, un fils de 14 ans, et deux filles de 11 et 6 ans. « Les enfants comprennent ce qu’il se passe. Ils sont un peu inquiets mais j’essaye de ne pas trop aborder le sujet. Ils savent que leur mère et leur sœur sont en sécurité. » Il a ajouté qu’il espère que « les droits de sa femme et de sa fille sont respectés, parce qu’elles sont des reines […] Nous avons tous des droits. » Ouest France

Protecting children at the border is complicated because there have, indeed, been instances of fraud. Tens of thousands of migrants arrive there every year, and those with children in tow are often released into the United States more quickly than adults who come alone, because of restrictions on the amount of time that minors can be held in custody. Some migrants have admitted they brought their children not only to remove them from danger in such places as Central America and Africa, but because they believed it would cause the authorities to release them from custody sooner. Others have admitted to posing falsely with children who are not their own, and Border Patrol officials say that such instances of fraud are increasing. (…) [Jessica M. Vaughan, the director of policy studies for the Center for Immigration Studies] said that some migrants were using children as “human shields” in order to get out of immigration custody faster. “It makes no sense at all for the government to just accept these attempts at fraud,” Ms. Vaughan said. “If it appears that the child is being used in this way, it is in the best interest of the child to be kept separately from the parent, for the parent to be prosecuted, because it’s a crime and it’s one that has to be deterred and prosecuted.” NYT

Over the weekend, you may have seen a horrifying story: Almost 1,500 migrant children were missing, and feared to be in the hands of human traffickers. The Trump administration lost track of the children, the story went, after separating them from their parents at the border. The news spread across liberal social media — with the hashtag #Wherearethechildren trending on Twitter — as people demanded immediate action. But it wasn’t true, or at least not the way that many thought. The narrative had combined parts of two real events and wound up with a horror story that was at least partly a myth. The fact that so many Americans readily believed this myth offers a lesson in how partisan polarization colors people’s views on a gut emotional level without many even realizing it. As other articles have explained, the missing children and the Trump administration’s separation of families who are apprehended at the border are two different matters. (…) These “missing” children had actually come to the United States without their parents, been picked up by the Border Patrol and then released to the custody of a parent or guardian. Many probably are not really missing. The figure represents the number of children whose households didn’t answer the phone when the Department of Health and Human Services called to check on them. The unanswered phone calls may warrant further welfare checks, but are not themselves a sign that something nefarious has happened. The Obama administration also detained immigrant families and children, as did other recent administrations. This past weekend, some social media users circulated a photo they said showed children detained as a result of President Trump’s policies, but the image was actually from 2014. (…) Long-running social science surveys have found that since the 1980s, Republicans’ opinions of Democrats and Democrats’ opinions of Republicans have been increasingly negative. At the same time, as Lilliana Mason, a political scientist at the University of Maryland, writes in a new book, partisan identity has become an umbrella for other important identities, including those involving race, religion, geography and even educational background. It has become a tribal identity itself, not merely a matter of policy preferences. So it’s not that liberals didn’t care about immigrant children until Mr. Trump became president, or that they’re only pretending to care now so as to score political points. Rather, with the Trump administration’s making opposition to immigrants a signature issue, the topic has become salient to partisan conflict in a way it wasn’t before. Mr. Trump’s treatment of immigrant families and children, when refracted through the lens of partisan bias, affirms liberals’ perception of being engaged in a broader moral struggle with the right, making it feel like an urgent threat. Mr. Obama’s detaining of immigrant children, by contrast, felt like a matter of abstract moral concern. Identity polarization means “you want to show that you’re a good member of your tribe,” Sean Westwood, a political scientist at Dartmouth College who studies partisan polarization, said in an interview early last year. “You want to show others that Republicans are bad or Democrats are bad, and your tribe is good.” Sharing stories on social media “provides a unique opportunity to publicly declare to the world what your beliefs are and how willing you are to denigrate the opposition and reinforce your own political candidates,” he said. Accurate news can serve that purpose. But fake news has an advantage. It can perfectly capture one side’s villainous archetypes of the other, without regard for pesky facts that might not fit the story line. The narrative that President Trump’s team lost hundreds of children after tearing them away from their parents combines some of the main liberal critiques of the administration: that it is racist, that it is authoritarian and that it is incompetent. The administration’s very real policy of separating families already plays to the first two archetypes. By adding in the missing children, the story manages to incorporate an incompetence angle as well. NYT

Nous ne voulons pas séparer les familles, mais nous ne voulons pas que des familles viennent illégalement. Si vous faites passer un enfant, nous vous poursuivrons. Et cet enfant sera séparé de vous, comme la loi le requiert. Jeff Sessions

Le dilemme est si vous êtes mou, ce que certaines personnes aimeraient que vous soyez, si vous êtes vraiment mou, pathétiquement mou… le pays va être envahi par des millions de gens. Et si vous êtes ferme, vous n’avez pas de coeur. C’est un dilemme difficile. Peut-être que je préfère être ferme, mais c’est un dilemme difficile. Donald Trump

Time has not responded to a request for comment from The Post, but in a statement sent to media outlets, the magazine said it’s standing by its cover. Washington Post

La photographie du 12 juin de la petite Hondurienne de 2 ans est devenue le symbole le plus visible du débat sur l’immigration en cours aux États-Unis et il y a une raison pour cela. Dans le cadre de la politique appliquée par l’administration, avant son revirement de cette semaine, ceux qui traversaient la frontière illégalement étaient l’objet de poursuites criminelles, qui entraînaient à leur tour la séparation des enfants et des parents. Notre couverture et notre reportage saisissent les enjeux de ce moment. Edward Felsenthal (rédacteur en chef de Time).

The Time cover is an illustration that interprets a wider issue being reported on within the magazine. The photograph I took is a straightforward and an honest image; it shows a brief moment in time of a distressed little girl, whose mother is being searched as they are both taken into custody. I believe this image has raised awareness of the zero tolerance policy of the current administration. Having covered immigration for Getty Images for 10 years, this photograph for me is part of a much larger story. John Moore

Obviously this child never met the president, it’s not misleading at all in that sense. I think that the power of it is in the juxtaposition of the two figures, of the child who quickly came to represent all of the children that we’re talking about, and the president who was making the decisions about their fate. Nancy Gibbs (former editor of Time)

It was well within the parameters of editorial license. This is a caustic, sharp-edged cover. But it’s a caustic, sharp-edged cover about an issue that is deeply emotional that has divided America. Moore’s photos are « iconic » and will be remembered alongside historic images of Emmett Till and the photo of a naked little girl running from a Naplam attack in Vietnam. Bruce Shapiro (Columbia University)

Il existe aux Etats-Unis un grave problème d’immigration illégale. Trump a commencé à prendre des décisions pour le régler. Les entrées clandestines dans le pays par la frontière Sud ont diminué de 70 pour cent. Elles sont encore trop nombreuses. Les immigrants illégaux présents dans le pays ne sont pas tous criminels, mais ils représentent une proportion importante des criminels incarcérés et des membres de gangs violents impliqués, entre autres, dans le trafic de drogue. Jeff Sessions, ministre de la justice inefficace dans d’autres secteurs, est très efficace dans ce secteur. Les Démocrates veulent que l’immigration illégale se poursuive, et s’intensifie, car ils ont besoin d’un électorat constitué d’illégaux fraîchement légalisés pour maintenir à flot la coalition électorale sur laquelle ils s’appuient et garder des chances de victoire ultérieure (minorités ethniques, femmes célibataires, étudiants, professeurs). La diminution de l’immigration clandestine leur pose problème. Les actions de la police de l’immigration (ICE; Immigration Control Enforcement) suscitent leur hostilité, d’où l’existence de villes sanctuaires démocrates et, en Californie, d’un Etat sanctuaire(démocrate, bien sûr). Ce qui se passe depuis quelques jours à la frontière Sud du pays est un coup monté auquel participent le parti démocrate, les grands médias américains, des organisations gauchistes, et le but est de faire pression sur Trump en diabolisant son action. La plupart des photos utilisées datent des années Obama, au cours desquelles le traitement des enfants entrant clandestinement dans le pays était exactement similaire à ce qu’il est aujourd’hui, sans qu’à l’époque les Démocrates disent un seul mot. Les enfants qui pleurent sur des vidéos ont été préparés à être filmés à des fins de propagande et ont appris à dire “daddy”, “mummy”. Le but est effectivement de faire céder Trump. Quelques Républicains à veste réversible ont joint leur voix au chœur. Trump, comme il sait le faire, a agi pour désamorcer le coup monté. On lui reproche de faire ce qui se fait depuis des années (séparer les enfants de leurs parents dès lors que les parents doivent être incarcérés) ? Il vient de décider que les enfants ne seront plus séparés des parents, et qu’ils seront placés ensemble dans des lieux de rétention. Cela signifie-t-il un recul ? Non. La lutte contre l’immigration clandestine va se poursuivre selon exactement la même ligne. Les parents qui ont violé la loi seront traités comme ils l’étaient auparavant. Les enfants seront-ils dans de meilleures conditions ? Non. Ils ne seront pas dans des conditions plus mauvaises non plus. Décrire les lieux où ils étaient placés jusque là comme des camps de concentration est une honte et une insulte à ceux qui ont été placés dans de réels camps de concentration (certains Démocrates un peu plus répugnants que d’autres sont allés jusqu’à faire des comparaisons avec Auschwitz !) : les enfants sont placés dans ce qui est comparable à des auberges pour colonies de vacances. Un enfant clandestin coûte au contribuable américain à ce jour 35.000 dollars en moyenne annuelle. Désamorcer le coup monté ne réglera pas le problème d’ensemble. Des femmes viennent accoucher aux Etats-Unis pour que le bébé ait la nationalité américaine et puisse demander deux décennies plus tard un rapprochement de famille. Des gens font passer leurs enfants par des passeurs en espérant que l’enfant sera régularisé et pourra lui aussi demander un rapprochement de famille. Des parents paient leur passage aux Etats Unis en transportant de la drogue et doivent être jugés pour cela (le tarif des passeurs si on veut passer sans drogue est de 10.000 dollars par personne). S’ils sont envoyés en prison, ils n’y seront pas envoyés avec leurs enfants. Quand des trafiquants de drogue sont envoyés en prison, aux Etats-Unis ou ailleurs, ils ne vont pas en prison en famille, et si quelqu’un suggérait que leur famille devait les suivre en prison, parce que ce serait plus “humain”, les Démocrates seraient les premiers à hurler. Les Etats-Unis, comme tout pays développé, ne peuvent laisser entrer tous ceux qui veulent entrer en laissant leurs frontières ouvertes. Un pays a le droit de gérer l’immigration comme il l’entend et comme l’entend sa population, et il le doit, s’il ne veut pas être submergé par une population qui ne s’intègre pas et peut le faire glisser vers le chaos. Les pays européens sont confrontés au même problème que les Etats-Unis, d’une manière plus aiguë puisqu’en Europe s’ajoute le paramètre “islam”. La haine de la civilisation occidentale imprègne la gauche européenne, qui veut la dissolution des peuples européens. Une même haine imprègne la gauche américaine, qui veut la dissolution du peuple américain. Les grandes villes de l’Etat sanctuaire de Californie sont déjà méconnaissables, submergées par des sans abris étrangers (pas un seul pont de Los Angeles qui n’abrite désormais un petit bidonville, et un quart du centre ville est une véritable cour des miracles, à San Francisco ce n’est pas mieux). Il n’est pas du tout certain que le coup monte servira les Démocrates lors des élections de mi mandat. Nombre d’Américains ne veulent pas la dissolution du peuple américain. Guy Millière

Sur le plateau de la NBCNews, l’ancien président du Comité national du parti Républicain, Michael Steele, vient de comparer les centres dans lesquels sont accueillis les enfants de clandestins aux Etats-Unis à des camps de concentration. Il s’adresse alors aux Américains : « Demain, ce pourrait être vos enfants ». La scène résume à elle seule la folie qui s’est emparée de la sphère politico-médiatique après que Donald Trump a ordonné aux autorités gardant la frontière mexicaine d’appliquer la loi et de séparer les parents de leurs enfants entrés illégalement aux Etats-Unis. Passons sur la comparaison. Aussi indécente que manipulatrice : ces enfants ne sont pas enfermés en attendant la mort. Quant à la mise en garde, elle est grotesque. Aucun Américain ne se verra subitement séparé de ses enfants. A moins d’avoir commis un crime ou un délit puni de prison. Quand un citoyen lambda est condamné à une peine de prison, personne ne s’offusque jamais de cette séparation … Jusqu’à ce que cela touche des clandestins. Leur particularité étant de n’avoir aucun logement dans le pays dont ils viennent de violer la frontière, leurs enfants sont donc pris en charge dans des camps, en attendant que la situation des adultes soit examinée. Aux frais des Américains. (…) Reste que les parents, prévenus de la loi que nul n’est censé ignorer, sont les premiers responsables du sort qui menace leurs enfants, en choisissant de la violer. Ce sont eux qui font payer leur délit à leur propre progéniture. Les clandestins sont des adultes tout aussi responsables que n’importe quel autre adulte : leur retirer leur capacité de décision, leur liberté et donc leur responsabilité n’est pas exactement les respecter. Mais (…) remontons à 2014, époque bénie du président Barack Obama. Cette année-là, 47.017 mineurs sont appréhendés, alors qu’ils traversent la frontière… seuls. Des enfants, envoyés par leurs parents qui n’ont apparemment pas eu peur de s’en séparer pour leur faire prendre des risques inconsidérés. Comment est-ce possible ? L’administration américaine d’alors avait affirmé que les étrangers envoyaient leurs enfants seuls, persuadés qu’ils seraient ainsi mieux traités que des adultes. Le New York Times avait donné raison à l’administration : « alors que l’administration Obama a évolué vers une attitude plus agressive d’expulsion des adultes, elle a, dans les faits, expulsé beaucoup moins d’enfants que par le passé. » Les clandestins le savent, tout comme ils connaissent aujourd’hui les risques qui pèsent sur leurs propres enfants. On apprend également qu’à l’époque, les enfants mexicains sont directement reconduits de l’autre côté de la frontière et que les autres sont « pris en charge par le département de la Santé et des Services humanitaires qui les place dans des centres temporaires en attendant que leur processus d’expulsion soit lancé. » En 2013, 80 centres accueillaient 25 000 enfants non accompagnés. Et ce, dans les mêmes conditions aujourd’hui dénoncées. Si similaires d’ailleurs que certains ont voulu critiquer la politique migratoire de Donald Trump en usant de photos datant de… 2014 ! Rien n’a changé. A un détail près. Les enfants dont on parle en ce mois de juin 2018 sont parfois accompagnés d’adultes. Comme sous l’administration Obama, les enfants sont séparés de ces adultes lorsqu’il y a un doute sur le lien réel de parenté, en cas de suspicion de trafic de mineurs ou par manque de place dans les centres de rétention pour les familles. Restent les enfants effectivement accompagnés de leurs parents et malgré tout séparés de ces derniers qui partent en prison. Chaque mois, 50.000 clandestins entrent aux Etats-Unis, parmi lesquels 15% de familles. Une fois arrêtés, les clandestins sont pénalement poursuivis avant toute demande d’asile. (…) Mais il a suffi de quelques images, publiées en même temps que la sortie du très attendu rapport sur la possible partialité du FBI lors des dernières élections présidentielles américaines, pour que l’opinion politico-médiatique hurle au scandale. Jusqu’à la première dame du pays, Mélania Trump, qui a confié « détester » voir les clandestins séparés de leurs enfants. Le Président lui-même a fini par douter publiquement : «Le dilemme est si vous êtes mou, ce que certaines personnes aimeraient que vous soyez, si vous êtes vraiment mou, pathétiquement mou… le pays va être envahi par des millions de gens. Et si vous êtes ferme, vous n’avez pas de coeur. C’est un dilemme difficile. Peut-être que je préfère être ferme, mais c’est un dilemme difficile.» Donald Trump a subi l’indignation générale (à moins d’en profiter), au point de montrer au monde que même lui avait du cœur en annonçant la signature d’un décret mettant fin à cette séparation forcée. Tout le monde s’est félicité du résultat de la mobilisation : enfin, les enfants vont pouvoir rejoindre leurs parents en prison ! Quelle victoire… Charlotte d’Ornellas

Cette administration a installé des camps de concentration à la frontière sud des États-Unis pour les immigrés, où ils sont brutalisés dans des conditions inhumaines et où ils meurent. Il ne s’agit pas d’une exagération. C’est la conclusion de l’analyse d’experts. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (18.06.2019)

Ils regardent avec horreur les enfants arrachés à leur famille et jetés dans des cages. Michelle Obama (2020)

Cette administration a arraché des bébés des bras de leur mère, et il semble que ces parents aient été, dans de nombreux cas, expulsés sans leurs enfants et n’ont pas été retrouvés. C’est un scandale, un échec moral et une tache sur nos valeurs nationales. Joe Biden (2020)

Attention: une manipulation peut en cacher beaucoup d’autres !

Au lendemain de la révélation que la petite Hondurienne de deux ans dont les larmes avaient fait le tour du monde comme symbole de la séparation des familles de migrants aux Etats-Unis …

N’avait en fait jamais été séparée de sa mère, comme a bien dû le reconnaitre – problème de « mauvaise formulation », s’il vous plait ! – le célèbre « Time magazine » lui-même qui en avait fait sa couverture …

Ayant même, selon les dires du père resté seul avec leurs trois autres enfants, été emmenée à son insu par sa mère après une première tentative il y a cinq ans non de fuir la violence de son Honduras natal comme il avait été dit mais de « réaliser son rêve américain »…

Et sans compter la fausse attribution à l’Administration Trump de photos d’enfants détenus datant de 2014 et donc, comme d’ailleurs la pratique elle-même (mesure de protection des enfants – faut-il le rappeler ? – que, sauf en Corée du nord, l’on n’emprisonne normalement pas avec leur parents délinquants), de l’Administration Obama qui l’avait précédée …

Comment ne pas repenser …

Au-delà de la véritable situation de chaos, y compris par le simple effet de leur nombre dans les centres de rétention, que fuient et subissent depuis au moins dix ans nombre de demandeurs d’asile …

Des enfants boucliers humains du Hamas au petit Mohammed ou au petit Aylan ou même tout dernièrement à la petite Leila de Gaza …

A non seulement, dévoyant et détournant ce singulier souci des plus faibles qui fait la singularité de l’Occident judéo-chrétien, l’irresponsabilité voire de l‘intention clairement criminelle de tous ces parents, appuyés par militants et ONG sansfrontieristes, qui exploitent ainsi la misère de leurs enfants …

Mais aussi à la lourde responsabilité de médias qui, entre deux « mauvaises formulations » ou manipulations, leur servent de caisse de résonance ou même les encouragent …

Et qui aujourd’hui n’ont que le mot « fake news » à la bouche quand il s’agit de qualifier les dires du président Trump ou des rares médias qui le défendent encore ?

Immigration. Pendant plusieurs jours, les médias du monde entier ont fait tourner en boucle des images d’enfants clandestins séparés de leurs parents à la frontière mexicano-américaine. Au point d’empêcher toute possibilité de réflexion.

Sur le plateau de la NBCNews, l’ancien président du Comité national du parti Républicain, Michael Steele, vient de comparer les centres dans lesquels sont accueillis les enfants de clandestins aux Etats-Unis à des camps de concentration. Il s’adresse alors aux Américains : « Demain, ce pourrait être vos enfants ».

La scène résume à elle seule la folie qui s’est emparée de la sphère politico-médiatique après que Donald Trump a ordonné aux autorités gardant la frontière mexicaine d’appliquer la loi et de séparer les parents de leurs enfants entrés illégalement aux Etats-Unis. Passons sur la comparaison. Aussi indécente que manipulatrice : ces enfants ne sont pas enfermés en attendant la mort. Quant à la mise en garde, elle est grotesque. Aucun américain ne se verra subitement séparé de ses enfants. A moins d’avoir commis un crime ou un délit puni de prison.

Quand un citoyen lambda est condamné à une peine de prison, personne ne s’offusque jamais de cette séparation … Jusqu’à ce que cela touche des clandestins. Leur particularité étant de n’avoir aucun logement dans le pays dont ils viennent de violer la frontière, leurs enfants sont donc pris en charge dans des camps, en attendant que la situation des adultes soit examinée. Aux frais des Américains.

Parce qu’un rappel n’est pas inutile dans le débat : franchir illégalement la frontière d’un pays est une violation de la loi. Un délit, puni d’emprisonnement aux Etats-Unis. Avec sa raison et non ses bons sentiments irrationnels, l’homme politique interrogé aurait donc pu être plus juste : si vous commettez un crime ou un délit passible de prison, vous aussi pourriez être séparés de vos enfants.

Reste que les parents, prévenus de la loi que nul n’est censé ignorer, sont les premiers responsables du sort qui menace leurs enfants, en choisissant de la violer. Ce sont eux qui font payer leur délit à leur propre progéniture. Les clandestins sont des adultes tout aussi responsables que n’importe quel autre adulte : leur retirer leur capacité de décision, leur liberté et donc leur responsabilité n’est pas exactement les respecter.

Certains ont voulu critiquer la politique migratoire de Donald Trump en usant de photos datant de… 2014

Mais penchons-nous plus précisément sur ce qui se passe à la frontière mexico-américaine. Et plutôt que de regarder la situation actuelle, qui ne saurait être analysée de manière raisonnable maintenant que Trump préside les Etats-Unis, remontons à 2014, époque bénie du président Barack Obama. Cette année-là, 47.017 mineurs sont appréhendés, alors qu’ils traversent la frontière… seuls.

Des enfants, envoyés par leurs parents qui n’ont apparemment pas eu peur de s’en séparer pour leur faire prendre des risques inconsidérés. Comment est-ce possible ? L’administration américaine d’alors avait affirmé que les étrangers envoyaient leurs enfants seuls, persuadés qu’ils seraient ainsi mieux traités que des adultes. Le New York Times avait donné raison à l’administration : « alors que l’administration Obama a évolué vers une attitude plus agressive d’expulsion des adultes, elle a, dans les faits, expulsé beaucoup moins d’enfants que par le passé. »

Les clandestins le savent, tout comme ils connaissent aujourd’hui les risques qui pèsent sur leurs propres enfants. On apprend également qu’à l’époque, les enfants mexicains sont directement reconduits de l’autre côté de la frontière et que les autres sont « pris en charge par le département de la Santé et des Services humanitaires qui les place dans des centres temporaires en attendant que leur processus d’expulsion soit lancé. » En 2013, 80 centres accueillaient 25 000 enfants non accompagnés. Et ce, dans les mêmes conditions aujourd’hui dénoncées. Si similaires d’ailleurs que certains ont voulu critiquer la politique migratoire de Donald Trump en usant de photos datant de… 2014 !

Rien n’a changé. A un détail près. Les enfants dont on parle en ce mois de juin 2018 sont parfois accompagnés d’adultes. Comme sous l’administration Obama, les enfants sont séparés de ces adultes lorsqu’il y a un doute sur le lien réel de parenté, en cas de suspicion de trafic de mineurs ou par manque de place dans les centres de rétention pour les familles.

Restent les enfants effectivement accompagnés de leurs parents et malgré tout séparés de ces derniers qui partent en prison. Chaque mois, 50.000 clandestins entrent aux Etats-Unis, parmi lesquels 15% de familles. Une fois arrêtés, les clandestins sont pénalement poursuivis avant toute demande d’asile. Or Trump a été élu pour une tolérance zéro : la loi est donc strictement appliquée. Cette même loi américaine ne permet pas que les enfants puissent suivre leurs parents lorsque ces derniers sont poursuivis pénalement. La séparation était donc une conséquence logique, même très pénible, du choix des Américains.

«Le dilemme est si vous êtes mou, le pays va être envahi par des millions de gens. Et si vous êtes ferme, vous n’avez pas de coeur»

C’est d’ailleurs ce qu’a immédiatement répondu le ministre américain de la justice Jeff Session : « Nous ne voulons pas séparer les familles, mais nous ne voulons pas que des familles viennent illégalement. Si vous faites passer un enfant, nous vous poursuivrons. Et cet enfant sera séparé de vous, comme la loi le requiert ».

Mais il a suffi de quelques images, publiées en même temps que la sortie du très attendu rapport sur la possible partialité du FBI lors des dernières élections présidentielles américaines, pour que l’opinion politico-médiatique hurle au scandale. Jusqu’à la première dame du pays, Mélania Trump, qui a confié « détester » voir les clandestins séparés de leurs enfants.

Le Président lui-même a fini par douter publiquement : «Le dilemme est si vous êtes mou, ce que certaines personnes aimeraient que vous soyez, si vous êtes vraiment mou, pathétiquement mou… le pays va être envahi par des millions de gens. Et si vous êtes ferme, vous n’avez pas de coeur. C’est un dilemme difficile. Peut-être que je préfère être ferme, mais c’est un dilemme difficile.»

Donald Trump a subi l’indignation générale (à moins d’en profiter), au point de montrer au monde que même lui avait du cœur en annonçant la signature d’un décret mettant fin à cette séparation forcée. Tout le monde s’est félicité du résultat de la mobilisation : enfin, les enfants vont pouvoir rejoindre leurs parents en prison ! Quelle victoire… Mais Donald Trump a insisté sur sa détermination à stopper l’immigration illégale en même temps, appelant de ses vœux un vote du Congrès pour « changer les lois ». Depuis son accession à la présidence, notamment due à un discours extrêmement ferme sur l’immigration, Donald Trump est empêché par les démocrates, comme par son administration : ils bloquent son projet de mur à la frontière, l’immigration fondée sur le mérite ainsi que tous les ajustements proposés pour les forces de l’ordre.

La situation finit par le servir, et il ne pouvait l’ignorer : il vient de faire une concession, il appelle maintenant le Congrès à voter contre les « anciennes lois horribles » en adoptant la sienne. Nul ne connaît la suite. Mais pour Donald Trump, le défi est immense. S’il n’a pas été élu sur la seule promesse d’une tolérance zéro vis-à-vis de l’immigration illégale, le sujet reste l’une des préoccupations majeures de ses électeurs.

Voir aussi:

Yanela, symbole des enfants séparés dans « Time magazine »… tout n’était pas tout à fait vrai

C’est une image qui a fait le tour du monde en quelques heures. Pour illustrer sa dernière Une, consacrée à la polémique autour de la politique migratoire de Donald Trump, le célèbre « Time Magazine » a réalisé un photomontage sur fond rouge qui met en scène une fillette en pleurs, sous les yeux du président, un sourire en coin. Le titre ? « Welcome to America » (Bienvenue en Amérique).

Sur le site de l’hebdomadaire, le photographe de l’agence Getty John Moore expliquait mercredi les coulisses du cliché, pris le 11 juin dernier à la frontière entre le Texas et le Mexique. Il a été réalisé au moment où les policiers étaient en train de fouiller la mère de la petite fille, âgée de 2 ans. « Dès qu’ils ont eu terminé, elles ont été mises dans un camion (…) Tout ce que je voulais, c’est la prendre avec moi. Mais je ne pouvais pas. »

Le photographe laisse également entendre que la mère et l’enfant, originaires du Honduras, ont pu être séparées par la suite, comme l’ont été au moins 23.000 enfants sans papiers depuis avril dernier, dans le cadre de politique de tolérance zéro menée par l’administration en matière migratoire. Face au tollé international, le président américain a annoncé mettre fin à ces séparations, expliquant également avoir été influencé par son épouse Melania.

Quid de la petite fille en une de « Time » ? Depuis la parution du magazine, de nombreux internautes ont relayé un appel pour aider à la retrouver, soutenus par de nombreuses personnalités comme les écrivains Don Winslow et Stephen King. Interrogé mercredi par le site américain Buzzfeed, un porte-parole de la police des frontière affirmait toutefois que mère et fille n’avait pas été séparées, sans donner plus de précision.

C’est finalement le père de la fillette qui a donné de ses nouvelles, ce vendredi. Dans un entretien téléphonique accordé au Daily Mail depuis le Honduras, Denis Javier Valera Hernandez, 32 ans, révèle que l’enfant s’appelle Yanela et qu’elle n’aurait pas été séparée de sa mère, Sandra. « Vous imaginez ce que j’ai ressenti lorsque j’ai vu la photo de ma fille. J’en ai eu le coeur brisé. C’est difficile pour un père de voir ça. Mais je sais maintenant qu’elles sont hors de danger. Elles sont plus en sécurité que lorsqu’elles ont fait le voyage vers la frontière. »

Denis Hernandez explique que sa femme et sa fille ont quitté leur pays en bateau, le 3 juin dernier, depuis le port de Puerto Cortes, sans le prévenir, afin de rejoindre des membres de sa famille déjà installés aux Etats-Unis. Pour effectuer le voyage, la mère aurait payé 6.000 dollars à un passeur. Depuis leur arrestation, Il affirme qu’elles sont détenues ensemble dans la ville frontalière de McAllen, au Texas, dans l’attente de l’examen d’un dossier de demande d’asile que la mère a déposé. S’il est refusé, elles seront contraintes de rentrer au Honduras.

« J’attends de voir ce qui va leur arriver », réagit le père dans un autre entretien accordé à l’agence de Reuters, qui a eu confirmation des faits par Nelly Jerez, la ministre des Affaires étrangères du Honduras. Ni les autorités américaines, ni « Time Magazine », n’ont commenté ces informations pour le moment. Et certains internautes continuent de les mettre en doute, tant que Yanela et sa mère n’auront pas été filmées par les caméras de télévision…

Quoi qu’il en soit, cet imbroglio vient mettre en lumière la difficulté de réunir les familles, dans la foulée de la décision spectaculaire de la Maison Blanche. D’après Jodi Goodwin, avocate spécialisée dans l’immigration au Texas, l’organisme ayant pris en charge les enfants ne dispose pas d’un système pour se synchroniser avec les autorités migratoires qui détiennent les parents et assurer ainsi une fluidité des informations.

« Lorsque je parle avec les parents, ils ont le regard fixé dans le vide parce qu’ils ne peuvent tout simplement pas comprendre, ils ne peuvent accepter, ils ne peuvent croire qu’ils ignorent où se trouvent leurs enfants et que le gouvernement américain les leur a retirés », a-t-elle expliqué à l’AFP. Un discours partagé dans les médias par de nombreuses ONG pour qui le revirement de Donald Trump n’est qu’une étape.

Rappelons que le décret, signé par le président américain devant les caméras, stipule que des poursuites pénales continueront à être engagées contre ceux qui traversent la frontière illégalement. Mais que parents et enfants seront détenus ensemble dans l’attente de l’examen de leur dossier. La petite Yanela et sa mère bénéficieront-elles de la clémence de la Maison Blanche ?

Voir de même: