Ma parole n’est-elle pas comme un feu, dit l’Éternel, et comme un marteau qui brise le roc? Jérémie 23: 29

Ma parole n’est-elle pas comme un feu, dit l’Éternel, et comme un marteau qui brise le roc? Jérémie 23: 29

De même que le marteau divise la roche en une multitude d’éclats, de même un seul verset frappé fait jaillir d’innombrables étincelles. Le Talmud (Traité Sanhédrin 34a)

En ce temps-là, un jour de sabbat, Jésus vint à passer à travers les champs de blé ; ses disciples eurent faim et commencèrent à arracher des épis de maïs, les frottèrent avec leurs mains et les mangèrent. Matthieu 12:1

L’Éternel Dieu fit à Adam et à sa femme des habits de peau, et il les en revêtit. Genèse 3: 21

Toute l’armée des cieux se dissout; les cieux sont roulés comme un livre, et toute leur armée tombe, comme tombe la feuille de la vigne, comme tombe celle du figuier. Esaïe 34: 4

Le ciel se retira comme un livre qu’on roule; et toutes les montagnes et les îles furent remuées de leurs places. Apocalypse 6: 14

Qui encore, si ce n’est toi, notre Dieu, a fait pour nous un firmament d’autorité au-dessus de nous, dans ta divine Écriture? Oui, le ciel se repliera comme un livre, et maintenant, comme une peau il est tendu au-dessus de nous. Ta divine Écriture en effet possède une plus sublime autorité, maintenant qu’ont subi la mort d’ici-bas ces mortels par qui tu nous l’as dispensée. Et tu sais, toi, Seigneur, tu sais comment tu as revêtu de peau les hommes, quand le péché les rendit mortels. Aussi as-tu étendu, comme une peau, le firmament de ton livre, je veux dire tes paroles concordantes que, par le ministère des mortels, tu as établies au-dessus de nous. Augustin

Or la peau du ciel, ne l’as-tu pas donnée comme un livre? Et qui donc que toi, notre dieu, nous fit un firmament d’autorité, par-dessus nous avec ton écriture divine? Car le ciel sera replié comme un livre et voici qu’à présent il est tendu par-dessus nous à la manière d’une peau. La pelisse que tu étires en tente sur nos têtes est faite en peau de bête, la même vêture que nos parents endossèrent après qu’ils eurent péché, la pelure des exilés pour voyager dans le froid et la nuit des vies perdues, noctambules trébuchant (…). La nuit qui nous éteint, suspendue sur nos yeux, n’est pourtant pas irrévocable comme la leur, aux bêtes. La peau dont l’écran nous interdit la vision claire ouvre le dos d’un livre replié, peut-être retourné. Notre ciel, tout indéchiffrable que le rende l’ombre qu’il projette dans nos regards, ne porte pas moins, sur sa face tournée vers nous, les signes de ton écriture. La couverture du volume relié à pleine peau, on la devine frappée de lettres. C’est que le firmament que tu jettes par-dessus nous en anathème annonce aussi ta promesse Jean-François Lyotard

Abel est celui qui sacrifie des animaux et nous sommes au stade : Abel n’a pas envie de tuer son frère peut-être parce qu’il sacrifie des animaux et Caïn, c’est l’agriculteur. Et là, il n’y a pas de sacrifices d’animaux. Caïn n’a pas d’autre moyen d’expulser la violence que de tuer son frère. Il y a des textes tout à fait extraordinaires dans le Coran qui disent que l’animal envoyé par Dieu à Abraham pour épargner Isaac est le même animal qui est tué par Abel pour l’empêcher de tuer son frère. Cela est fascinant et montre que le Coran n’est pas insignifiant sur le plan biblique. C’est très métaphorique mais d’une puissance incomparable. Cela me frappe profondément. Vous avez des scènes très comparables dans l’Odyssée, ce qui est extraordinaire. Celles du Cyclope. Comment échappe-t-on au Cyclope ? En se mettant sous la bête. Et de la même manière qu’Isaac tâte la peau de son fils pour reconnaître, croit-il, Jacob alors qu’il y a une peau d’animal, le Cyclope tâte l’animal et voit qu’il n’y a pas l’homme qu’il cherche et qu’il voudrait tuer. Il apparaît donc que dans l’Odyssée l’animal sauve l’homme. D’une certaine manière, le troupeau de bêtes du Cyclope est ce qui sauve. On retrouve la même chose dans les Mille et une nuits, beaucoup plus tard, dans le monde de l’islam et cette partie de l’histoire du Cyclope disparaît, elle n’est plus nécessaire, elle ne joue plus un rôle. Mais dans l’Odyssée il y a une intuition sacrificielle tout-à-fait remarquable. (…) L’absence de lieu non sacrificiel où l’on pourrait s’installer pour rédiger une science du religieux, qui n’aurait aucun rapport avec lui, est une utopie rationaliste. Autrement dit il n’y a que le religieux chrétien qui lise vraiment de façon scientifique le religieux non chrétien. René Girard

Les Psaumes sont comme une fourrure magnifique de l’extérieur, mais qui, une fois retournée, laisse découvrir une peau sanglante. Ils sont typiques de la violence qui pèse sur l’homme et du recours que celui-ci trouve dans son Dieu. René Girard

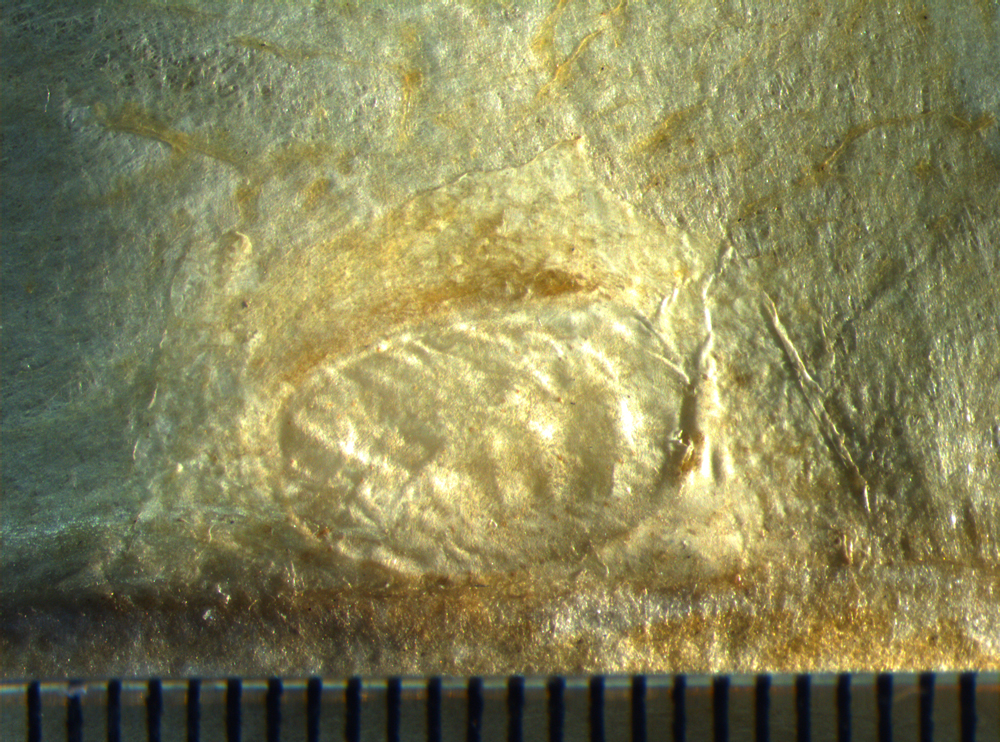

Les textes étaient (…) recopiés sur du parchemin, issus de peaux de bêtes séchées, matériel rare et coûteux à l’époque, ce qui conduisait les moines à réutiliser des pages déjà rédigées pour les réemployer. Ils lavaient alors à grande eau ces feuilles de parchemin solides et épaisses pour faire disparaître les lignes écrites. Une fois séchées, ils recopiaient un autre texte. Cela pouvait se produire plusieurs fois au cours des siècles suivants. On appelle ces parchemins réutilisés des palimpsestes. Le fragment retrouvé en syriaque se trouvait donc effacé, sous un texte liturgique géorgien visible, et sous un texte grec d’un Père de l’Église, ces théologiens du premier millénaire, deuxième utilisation elle aussi éclipsée. C’est par la photographie sous lumières ultraviolettes et multi-spectrale que ces trois textes, en trois langues, copiés successivement sur la même page, ont été rendus visibles. Ils sont ensuite devenus lisibles par un traitement numérique qui a séparé les types de phrases entremêlés, en délimitant trois versions grâce aux différences de formes de caractères des lettres. Jean-Marie Guénois

Le parchemin était, bien entendu, le matériau le plus beau et le plus adapté à l’écriture ou à l’impression qui ait jamais été utilisé, sa surface étant singulièrement uniforme et offrant peu ou pas de résistance à la plume, de sorte que toutes les sortes d’écritures peuvent y être réalisées avec la même facilité. Bien que le sens exact des mots « parchemin » et « vélin » soit celui qui vient d’être expliqué, et bien que certains érudits emploient le premier pour désigner la peau de mouton et le second pour la peau de veau, dans l’usage courant mais incorrect, les deux mots sont synonymes. Le mot « parchemin » (français, parchemin ; allemand, Pergament ; italien, pergamena) – dérivé du grec Pergam né et du latin Pergamena (ou charta Pergamena), c’est-à-dire de l’étoffe préparée à Pergame, qui était une ville et un royaume importants d’Asie mineure – est strictement associé à un événement marquant de l’histoire de ce matériau d’écriture. Selon Pline l’Ancien, citant l’écrivain romain Varro, le roi Ptolémée d’Égypte – il s’agit probablement de Ptolémée V Épiphane (v. 205 – v. 185 av. J.-C.) – jaloux d’un collectionneur de livres rival, craignait que la bibliothèque d’Eumène, roi de Pergame – probablement Eumène II (v. 197 – c. 159 av. J.-C.) – en vienne à surpasser la bibliothèque d’Alexandrie, et il impose donc un embargo sur l’exportation de papyrus en provenance d’Égypte, afin de retarder les progrès littéraires de la ville rivale. Eumène, ne pouvant plus se procurer de rouleaux de papyrus, fut contraint d’inventer le parchemin. Cela impliquerait que le parchemin a été inventé vers la première décennie du deuxième siècle avant J.-C. Mais ce récit n’est pas considéré comme historique. De plus, le parchemin ne peut être considéré comme une véritable invention. Il est plutôt le résultat d’une lente évolution ou d’une amélioration d’une pratique ancienne, à savoir l’utilisation de peaux d’animaux comme matériau d’écriture. Alors que le cuir est simplement tanné, la fabrication du parchemin est beaucoup plus compliquée ; la peau (de mouton, d’agneau, de chevreau, de chèvre, d’âne, de porc ou de bovin, surtout de veau), lavée et débarrassée de ses poils ou de sa laine, est trempée dans une fosse à chaux, tendue sur un cadre et débarrassée des poils restants d’un côté et de la chair de l’autre ; il est ensuite mouillé avec un chiffon humide, recouvert de craie pilée et frotté avec de la pierre ponce ; enfin, il est mis à sécher dans le cadre. On ne sait pas exactement quand et comment s’est opéré le passage du cuir au parchemin pour l’écriture. L’utilisation de peaux d’animaux pour l’écriture était cependant familière dans l’Antiquité en Égypte, en Mésopotamie, en Palestine, en Perse, en Asie Mineure et dans d’autres pays. (…) Il est cependant très probable qu’avant l’introduction du parchemin, la peau, en raison de son coût, était beaucoup moins utilisée que le papyrus et n’a jamais été d’un usage général. En effet, elle était principalement utilisée pour les documents importants ou officiels. Les découvertes archéologiques semblent confirmer ce point de vue. Si, comme nous l’avons déjà expliqué, le papyrus était le principal support d’écriture, des supports moins coûteux, tels que les ostraca et les petites tablettes de bois, étaient utilisés par des personnes plus pauvres ou à des fins purement éphémères. (…) De nombreux faits suggèrent que les anciens Hébreux ont très tôt utilisé le cuir comme matériau d’écriture. (…) Cette tradition est sans doute à l’origine de la règle du Talmud selon laquelle toutes les copies de la Torah (ou « Loi ») doivent être écrites sur des rouleaux (ou parchemins) de peau ; grâce à cette règle, qui est toujours en vigueur, il existe plusieurs milliers de parchemins de la Loi dans les synagogues juives du monde entier. (…) Une autre preuve de l’utilisation du cuir ou du parchemin pour les rouleaux de la Loi hébraïque est fournie par la « lettre » du Pseudo-Aristeas (aujourd’hui attribuée au milieu du deuxième siècle avant J.-C.), qui fait référence à une magnifique copie de la Loi écrite sur diphthérai, c’est-à-dire sur cuir, en lettres d’or, qui aurait été envoyée au roi Ptolémée Ier (d’Égypte) en 285 avant J.-C., dans le but de réaliser la traduction septuagint de la Bible hébraïque en grec. Cependant, il est très probable que le cuir coûteux était le matériau habituel pour les documents importants ou officiels ainsi que pour les copies formelles, tandis que le papyrus (voir chapitre IV) et l’ostraca – comme le prouvent les découvertes faites à Samarie, à Lachish, à Jérusalem et en d’autres lieux -étaient employés pour des affaires plus ou moins privées et simplement éphémères. Dans la colonie juive d’Eléphantine (voir p. 148 et suivantes), on a trouvé, à côté des fameux papyrus, un fragment de cuir qui contient quelques lignes brisées d’un texte araméen : on l’attribue au cinquième siècle avant J.-C. (…) Il y avait probablement beaucoup de livres hébraïques anciens ; mais dans le sol humide de la Palestine, on ne peut s’attendre à ce qu’aucun cuir ou papyrus subsiste jusqu’à notre époque, à moins qu’il ne soit conservé dans des conditions semblables à celles dont il est question dans le livre de Jérémie : » Ainsi parle le Seigneur des armées, le Dieu d’Israël, xxxii, 14 : « Ainsi parle le Seigneur des armées, le Dieu d’Israël : Prends ces actes … et mets-les dans un vase de terre, afin qu’ils subsistent longtemps. (…) Il a déjà été indiqué que l’on ne sait pas exactement quand et comment le parchemin a été introduit. Le parchemin, il faut le souligner, est un cuir fabriqué de manière plus élaborée. On peut donc supposer que l’évolution constante du processus de fabrication du cuir s’est poursuivie pendant des siècles. C’est peut-être la raison pour laquelle, pendant quelques siècles, les Grecs n’ont pas eu de terme particulier pour désigner le « parchemin » ; ils ont continué à employer le mot diphthéra, qui signifie « cuir » (c’était aussi le mot ionien pour désigner le « livre ») ; ou ils ont utilisé le terme latin membrána (voir, par exemple, 2 Tim., iv, 13, tà biblía, málista tàs membránas, « les livres, surtout les parchemins »). Ce n’est qu’en l’an 301 – dans l’édit de Dioclétien – qu’apparaît le terme grec pergam éné. (…) En résumé, du fait qu’au début du deuxième siècle avant J.-C. le parchemin était utilisé dans un avant-poste comme Doura-Europos, on peut supposer avec certitude qu’il était utilisé dans des endroits plus centraux au moins à la fin du troisième siècle avant J.-C. L’histoire concernant l’invention du parchemin par Eumène II, telle qu’elle est racontée aux pages 170 et suivantes, peut contenir la vérité que Pergame était un emporium particulièrement important pour le commerce du parchemin et un grand centre pour sa fabrication, peut contenir la vérité que Pergame était un emporium particulièrement important pour le commerce du parchemin et un grand centre pour sa fabrication, probablement avec l’aide de quelques nouveaux appareils par lesquels le produit de Pergame, c’est-à-dire le « parchemin », est devenu célèbre. Il se peut également qu’à l’époque d’Eumène II, le parchemin ait temporairement pris le dessus en tant que matériau pour la production de livres. (…) L’introduction du parchemin a donné naissance à un matériau d’écriture fin et lisse, de couleur presque blanche, capable de recevoir une écriture sur les deux faces et d’une grande résistance. Les principales qualités du parchemin – dont la fabrication a été considérablement améliorée par la suite – et surtout du vélin, sont sa finesse semi-transparente et la beauté frappante de son poli, en particulier sur le côté chair. Le côté chair du parchemin est un peu plus foncé, mais il retient mieux l’encre. Les avantages du parchemin sur le papyrus étaient évidents : c’était un matériau beaucoup plus résistant et durable que le fragile papyrus ; les feuilles pouvaient être écrites des deux côtés ; L’encre, surtout si elle est récente, peut être facilement enlevée pour être corrigée, et la surface peut être rendue disponible pour une seconde écriture (un manuscrit d’occasion de ce type est connu sous le nom de « palimpseste »). Avec tous ces avantages et d’autres encore, le conservatisme naturel du monde antique, ainsi que les traditions du commerce du livre, en particulier parmi les non-chrétiens, n’ont été surmontés que progressivement. Cependant, même le parchemin n’était pas exempt de défauts : par exemple, dans les codex en parchemin, les bords des feuilles ont tendance à s’effriter. En outre, il était beaucoup plus lourd que le papyrus et plus difficile à manipuler. (…) Le parchemin était en concurrence avec les tablettes de cire plutôt qu’avec le papyrus et, généralement relié sous forme de codex, il était utilisé pour les livres de comptes, les testaments et les notes. Le membrana mentionné par Horace (Sat., ii, 3, 2) était utilisé pour la copie grossière de poèmes destinés à être modifiés et publiés plus tard, et le parchemin d’un diptyque taché de jaune mentionné par Juvénal (vii, 24) servait le même objectif. Le parchemin était le matériau le plus lourd et le plus vulgaire ; il était clairement considéré comme inférieur au papyrus. Les livres écrits en pugillaribus membranis ou en membranis sont des cadeaux de moindre valeur (Martial, xiv, 183-96). Bien après la période augustinienne, la charta, qui signifie « papyrus », était utilisée pour les publications littéraires en général. En effet, toutes les références de la littérature romaine jusqu’à la fin du premier siècle de l’ère chrétienne concernent clairement le papyrus, considéré par Pline « comme l’organe principal et essentiel de la civilisation et de l’histoire humaines ». Curieusement, même à la fin du IVe siècle de notre ère, et même dans le monde chrétien, « dans un pays très éloigné de l’Egypte, nous trouvons Augustin s’excusant d’utiliser du vélin pour une lettre, au lieu du papyrus ou de ses tablettes privées, qu’il a expédiées ailleurs » (Kenyon). Cependant, comme nous l’avons déjà indiqué, la croissance de la communauté chrétienne a mis le parchemin à l’honneur, et c’est dans la première moitié du quatrième siècle après J.-C. que le vélin ou le parchemin a définitivement supplanté le papyrus en tant que matériau utilisé pour les meilleurs livres. C’est à peu près à la même époque que l’empereur Constantin le Grand a proclamé le christianisme religion d’État de l’Empire romain. David Diringer

Il y a environ 1 300 ans, un scribe de Palestine a pris un livre des Évangiles portant une inscription en syriaque et l’a effacé. Le parchemin étant rare dans le désert au Moyen Âge, les manuscrits étaient souvent effacés et réutilisés. Un médiéviste de l’Académie autrichienne des sciences (OeAW) a maintenant réussi à rendre à nouveau lisibles les mots perdus sur ce manuscrit stratifié, appelé palimpseste : Grigory Kessel a découvert l’une des plus anciennes traductions des Évangiles, réalisée au IIIe siècle et copiée au VIe siècle, sur des pages individuelles de ce manuscrit. « La tradition du christianisme syriaque connaît plusieurs traductions de l’Ancien et du Nouveau Testament », explique le médiéviste Grigory Kessel. « Jusqu’à récemment, seuls deux manuscrits étaient connus pour contenir la traduction en vieux syriaque des évangiles. L’un d’entre eux est aujourd’hui conservé à la British Library de Londres, tandis que l’autre a été découvert sous forme de palimpseste au monastère Sainte-Catherine du Mont Sinaï. Les fragments du troisième manuscrit ont été récemment identifiés dans le cadre du « Sinai Palimpsests Project ». Le petit fragment de manuscrit, qui peut désormais être considéré comme le quatrième témoin textuel, a été identifié par Grigory Kessel à l’aide de la photographie aux ultraviolets comme la troisième couche de texte, c’est-à-dire le double palimpseste, dans le manuscrit de la Bibliothèque du Vatican. Ce fragment est à ce jour le seul vestige connu du quatrième manuscrit qui atteste de la version syriaque ancienne – et offre une porte d’entrée unique sur la toute première phase de l’histoire de la transmission textuelle des Évangiles. Par exemple, alors que l’original grec du chapitre 12 de Matthieu, verset 1, dit : « En ce temps-là, Jésus traversait les champs de blé le jour du sabbat ; ses disciples eurent faim et se mirent à cueillir les épis et à manger », la traduction syriaque dit : « […] se mirent à cueillir les épis, à les frotter dans leurs mains et à les manger ». Académie autrichienne des sciences

Un parchemin est une peau d’animal, généralement de mouton, parfois de chèvre ou de veau, qui est apprêtée spécialement pour servir de support à l’écriture. Par extension, il en est venu à désigner aussi tout document écrit sur ce type de support. (…) Succédant au papyrus, principal médium de l’écriture en Occident jusqu’au VIIe siècle, le parchemin a été abondamment utilisé durant tout le Moyen Âge pour les manuscrits et les chartes, jusqu’à ce qu’il soit à son tour détrôné par le papier. Son usage persista par la suite de façon plus restreinte, à cause de son coût très élevé. D’après Pline l’Ancien, le roi de Pergame aurait introduit son emploi au IIe siècle av. J.-C. à la suite d’une interdiction des exportations de papyrus décrétée par les Égyptiens, qui craignaient que la bibliothèque de Pergame surpassât celle d’Alexandrie. Ainsi, si des peaux préparées avaient déjà été utilisées pendant un ou deux millénaires, le « parchemin » proprement dit (mot dérivé de pergamena, « peau de Pergame ») a été perfectionné vers le IIe siècle av. J.-C. à la bibliothèque de Pergame en Asie Mineure. (…) Les peaux animales sont dégraissées et écharnées pour ne conserver que le derme. Par la suite elles sont trempées dans un bain de chaux, raclées à l’aide d’un couteau pour ôter facilement les poils et les restes de chair, et enfin amincies, polies et blanchies avec une pierre ponce et de la poudre de craie. Une fois la préparation achevée, on peut distinguer une différence de couleur et de texture entre le « côté poil » (appelé également « côté fleur ») et le côté chair. Cette préparation permet ainsi l’écriture sur les deux faces de la peau. Selon l’animal, la qualité du parchemin varie (épaisseur, souplesse, grain, texture, couleur…). Le parchemin est découpé en feuilles. « D’après les calculs effectués, à partir des dimensions du rectangle de parchemin obtenu d’une peau de mouton, les manuscrits de grands formats, d’une hauteur supérieure à 400 mm et de 200 à 250 folios, nécessitaient 100 à 125 peaux de mouton ». Copier une Bible complète nécessitait 650 peaux de moutons, d’où le prix élevé de sa copie. Les feuilles peuvent être assemblées sous différentes formes : le volumen est un ensemble de feuilles cousues bout à bout et forme un rouleau (utilisé jusqu’au IVe-Ve siècle). On le retrouve encore très souvent au XVe siècle, par exemple en Bretagne, pour servir à la longue rédaction des procès. Le codex (utilisé à partir du Ier-IIe siècle) est un ensemble de feuilles cousues en cahiers et peut être considéré comme l’ancêtre du livre moderne. Les parchemins en peau de veau mort-né, d’une structure très fine, sont appelés vélins. Ils diffèrent des parchemins par leur aspect demi-transparent. Ils sont fabriqués à partir de très jeunes veaux, les plus beaux et les plus recherchés provenant en général du fœtus. Le parchemin est un support complexe à fabriquer, onéreux (environ 10 fois plus cher que le papier), mais extrêmement durable dans le temps. Si les papiers habituels jaunissent en quelques années, on trouve aux archives nationales quantité de parchemins encore parfaitement blancs, et dont l’encre est parfaitement noire. Aussi, il offre l’avantage d’être plus résistant et permet le pliage. Il fut le seul support des copistes européens au Moyen Âge jusqu’à ce que le papier apparaisse et le supplante. À la fin du XIVe siècle, il est utilisé essentiellement pour la réalisation de documents précieux, d’imprimés de luxe ou encore pour réaliser des reliures. Support onéreux, on évitait de le gaspiller. Aussi réparait-on les peaux abîmées avec du fil et on réutilisait les vieux parchemins après que l’écriture en avait été grattée : on les appelle les palimpsestes. Wikipedia

Codex Sinaiticus was written on prepared animal skin, called parchment. Parchment is very often made from calf, goat or sheep’s skin and has been widely used as a writing support. The making process of lime soaking, de-hairing, stretching and scraping skins has remained essentially the same for over two millennia. Being animal skin, parchment has a ‘flesh’ (facing the inner body of the animal) and a ‘hair’ (from which the hair grew) side. The ‘flesh’ side tends to be lighter in colour and smoother in appearance whilst the ‘hair’ side tends to be darker, less smooth and in some cases easily identifiable by remains of the actual hair follicles. Skin characteristics such as follicle patterns, skeletal marks, scar tissue and variance of colour can tell us much about the type of animal and its condition. Other man-made characteristics like makers’ holes and repairs, striation, uniformity of thinness, and veining evidence tell us much about the quality of process and skill of workmanship All these features have been recorded on the documentation form. Follicle patterns vary according to the animal of origin and can be used to identify the type of animal. The location and amount of follicle marks can also be indicative of the size of the beast, where on the skin the parchment was cut from, and the quality of the workmanship. Follicles are often visible on the axilla area, which is the loosely structured and stretchy area of the animal skin behind the forelegs and in front of the hind legs. Such areas are also characterized by a more widely spaced hair follicle network. Axilla evidence can indicate the size of the animal which in turn informs the identification process. In prepared skins this will tend to appear at the outer edges and more rippled than the rest of the skin. Due to the way the skin is folded to form bifolia, axilla is frequently found at the edges of the leaves. Other characteristic marks, some times found along the outer edges of the folia, are caused by proximity to the animal’s skeleton and, particularly, from the highpoints of the pelvic, spine and shoulder areas. They often appear as dark patches clearly visible in transmitted light. On the documentation form the Conservators referred to these evidences as ‘skeletal marks’ and recorded the area where they were visible. Injuries sustained by animals whilst alive are often still visible on the parchment produced from their skins. They appear as a thinner tissue (scar tissue) which grows over to heal an injury. The amount of scarring evident can indicate the quality of life the beast may have had as well as informing the observer about the quality of parchment selection Parchment can sometimes still show evidence of the vein network which will appear of a light colour if the animal has been bled thoroughly or dark if this process has been poorly done. Conservators called the visible vein network ‘veining’. The occasional jagging action of the knives when thinning down the skin could also sometimes leave parallel marks on the parchment. This type of damage is called striation. The knives used by parchment makers to de-hair and scrape the stretched skin could leave marks on the parchment. Any minor damage to the skin could end up as a hole after stretching, unless these holes were repaired. The conservators recorded the location of such un-repaired parchment maker’s holes as well as of the parchment maker’s repairs. The folios are made of vellum parchment primarily from calf skins, secondarily from sheep skins … Most of the quires or signatures contain four leaves save two containing five. It is estimated that about 360 animals were slaughtered for making the folios of this codex, assuming all animals yielded a good enough skin. Codex sinaiticus project

The oldest known complete Bible is the Codex Sinaiticus, which was produced in 350AD or thereabouts. It’s a copy in one volume of most of the then known books of the Bible. Its 1478 pages required 370 animal skins – sheep and cows – to make. Study the pages closely and you can still see veins, follicles, scars (In 700 AD when the burghers of Jarrow ordered three copies of the complete Bible made, they petitioned the crown for the additional land required to raise the 2000 animals that would be needed for the pages: in those days ordering a book had remarkable economic and environmental consequences). The scribes who transcribed it sometimes forgot bits, or repeated themselves, or changed the meaning by annotating in the margins, their judgments and idiosyncracies subtly altering the meaning of the sacred texts. It took a few more centuries and the printing press to introduce standardised editions that allowed the Church and other bodies to decree a literary or religious canon of unchallenged texts. David Parker, professor of theology at Birmingham, and a scholar of early religious texts, has helped bring the Codex to a global audience by putting it online and allowing anyone to do what previously only scholars could, namely study the different bits – held in London, St Petersburg and St Catherine’s monastery in Sinai – and draw their own conclusions. But at his session he went further by suggesting that in a digital age when we can each download the Bible to our tablet or smartphone, annotate it, share it, edit it, and alter its phrases, we are subverting the very idea of a set text, of a religious canon. (…) Which, if you think about it, poses some fundamental questions for the Church. If he is right, and we are entering an age in which we will each be able to edit out own Bible, or Torah, or even Koran, what does that mean for the authority of established religions. Who decides the canon? Benedict Brogan

The last fragments, from the lecture “The Skin of the Skies,” comment a passage from Confessions XIII xv in which Augustine envisions the firmament as covered by a tent, made by the skin that Adam and Eve had to wear after the Fall (Augustine’s interpretation of Isaiah xxxiv, 3-4). Though this eternal night is the punishment of Yahweh, the skin of the Heaven at the same time bears the Holy Scripture as inscription: the signs of bestiality have been transformed into the Holy Scripture. Hanne Roer

We can get so much onto an iPhone or tablet that the idea of a canon of texts is out of date. How in the digital age are we going to change our attitude to sacred scripture ? The history of Christianity has been ruled by the idea of set texts. In the world we are entering into the idea of the Bible will be fundamentally different. Do we really need authorised texts? What happens if we accept they don’t exist? What my grandchildren will be able to do with it is beyond my imagination. I’m pretty sure they won’t have the same view of sacred texts that I inherited. David Parker

Comme beaucoup de chercheurs, je suis à la veille de faire le grand saut dans le cyberespace, et j’ai peur. Que vais-je y trouver? Que vais-je y perdre? Vais-je m’y perdre moi-même? Robert Darnton (directeur des bibliothèques de Harvard)

Alors que revient dans l’actualité …

Grâce aux nouvelles techniques de la photographie multi-spectrale sous lumières ultraviolettes …

Et aux fameux palimpsestes, ces parchemins qui, issus de peaux de bêtes et donc très rares et très chers, étaient souvent effacés et réutilisés …

La redécouverte d’une toute petite variante du fameux texte de Matthieu du Seigneur du sabbat …

Retour sur ces précieux parchemins auxquels nous devons la transmission jusqu’à nous de la plupart de nos textes les plus anciens de la Bible …

Et qui pour la plus ancienne Bible complète connue pouvait nécessiter jusquà 370 peaux d’animaux, moutons ou vaches …

Dont on peut encore voir les veines, les follicules et les cicatrices …

Rappelant comme l’avait remarqué Saint Augustin …

Entre la peau dont le Créateur avait revêtu nos premiers parents après le premier péché …

Et le firmament, dont on nous dit qu’il a été étendu au-dessus de nous comme un livre …

Le sanglant coût, les signes de notre bestialité transformés en Ecriture sainte, de notre salut …

Mais aussi avec le remplacement par le papier dix fois moins cher mais si peu durable …

Ou, plus fragile encore, l’écriture électronique de nos ordinateurs et tablettes …

La question même de la survie de tout notre patrimoine ?

Benedict Brogan’s Hay Week

A personal view from Hay Festival 2013, the greatest literary festival in the world

Benedict Brogan

Daily Telegraph

31 May 2013

(…)

The oldest known complete Bible is the Codex Sinaiticus, which was produced in 350AD or thereabouts. It’s a copy in one volume of most of the then known books of the Bible. Its 1478 pages required 370 animal skins – sheep and cows – to make. Study the pages closely and you can still see veins, follicles, scars (In 700AD when the burghers of Jarrow ordered three copies of the complete Bible made, they petitioned the crown for the additional land required to raise the 2000 animals that would be needed for the pages: in those days ordering a book had remarkable economic and environmental consequences). The scribes who transcribed it sometimes forgot bits, or repeated themselves, or changed the meaning by annotating in the margins, their judgments and idiosyncracies subtly altering the meaning of the sacred texts. It took a few more centuries and the printing press to introduce standardised editions that allowed the Church and other bodies to decree a literary or religious canon of unchallenged texts.

David Parker, professor of theology at Birmingham, and a scholar of early religious texts, has helped bring the Codex to a global audience by putting it online and allowing anyone to do what previously only scholars could, namely study the different bits – held in London, St Petersburg and St Catherine’s monastery in Sinai – and draw their own conclusions. But at his session he went further by suggesting that in a digital age when we can each download the Bible to our tablet or smartphone, annotate it, share it, edit it, and alter its phrases, we are subverting the very idea of a set text, of a religious canon. « We can get so much onto an iPhone or tablet that the idea of a canon of texts is out of date, » he said. « How in the digital age are we going to change our attitude to sacred scripture? » he asked. « The history of Christianity has been ruled by the idea of set texts. In the world we are entering into the idea of the Bible will be fundamentally different. » Which, if you think about it, poses some fundamental questions for the Church. If he is right, and we are entering an age in which we will each be able to edit out own Bible, or Torah, or even Koran, what does that mean for the authority of established religions. Who decides the canon? « Do we really need authorised texts? What happens if we accept they don’t exist? » he asked. « What my grandchildren will be able to do with it is beyond my imagination. I’m pretty sure they won’t have the same view of sacred texts that I inherited. »

(…)

La vraie fausse découverte d’un « nouveau » texte de l’Évangile

Jean-Marie Guénois

Le Figaro

14/04/2023

DÉCRYPTAGE – Certains médias français annoncent la découverte d’un « nouveau » passage de l’Évangile dans la Bibliothèque du Vatican. À tort.

La bibliothèque du Vatican n’a pas encore livré tous ses secrets comme Le Figaro a pu l’expliquer récemment. Certains médias français viennent pourtant d’annoncer qu’un passage « inconnu » de l’Évangile aurait été découvert, au Vatican, par un chercheur russe associé à l’Académie autrichienne, Grigory Kessel. Ce qui est faux.

Le passage en question est en effet connu. C’est sa traduction en syriaque ancien – une langue sémitique, issue des langues araméennes – qui l’était moins. Elle est tirée d’un texte originel et classique, rédigé en grec, relatant le verset 1 du chapitre XII de l’Évangile de Saint Matthieu.

Traduction vers le syriaque ancien

Le texte grec – connu – dit : «En ce temps-là, un jour de sabbat, Jésus vint à passer à travers les champs de blé ; ses disciples eurent faim et ils se mirent à arracher des épis et à les manger». Le fragment retrouvé, écrit : «commencèrent à arracher des épis de maïs, ils se frottèrent avec ses [?] mains et mangèrent». Pas de nouveauté donc, sinon ce détail qui ne change rien au sens de l’histoire : les disciples «se frottèrent les mains».

Par ailleurs, cette soi-disant «découverte» d’un nouveau fragment, daté du VI° siècle, confirme une nouvelle fois l’existence certaine d’une traduction de cet Évangile de Matthieu, à partir de sa version grecque, vers le syriaque ancien. Deux autres fragments en syriaque avaient déjà été découverts avant 2016 et un troisième le fut cette année-là. Ils sont conservés à la British Library à Londres, à la bibliothèque du monastère Sainte-Catherine au Mont Sinaï en Égypte et au Vatican.

Le fragment de ce manuscrit de la bibliothèque apostolique du Vatican atteste l’existence de traductions de l’Évangile vers le syriaque, plus anciennes qu’on ne le pensait. Elles remonteraient au III° siècle. Soit bien avant les manuscrits grecs qui ont pu traverser les âges et qui sont pourtant la matrice de ces traductions. Quant à la date de rédaction du fragment découvert, il serait du VI° siècle.

Mais contrairement aux affirmations de l’Académie de Vienne qui a lancé cette nouvelle le 6 avril par communiqué comme une «découverte», il apparaît que, non seulement, la bibliothèque du Vatican connaissait ce fragment – redécouvert il y a une dizaine d’années et déjà signalé comme une trace de l’évangile de Matthieu par Bernard Outtier dans les années 70 – et sur lequel elle avait déjà publié trois articles, dans sa revue, The Vatican Library Review, – et une notice scientifique le décrivant – mais que c’est elle qui avait commandé l’étude scientifique de ce fragment et réalisé le traitement par images multi-spectrales. La paternité de cette «découverte» revient donc au Vatican.

Palimpsestes

En effet, comment cette «découverte» a-t-elle été réalisée ? Par un travail de haute technologie sur des documents antiques. Les textes étaient en effet recopiés sur du parchemin, issus de peaux de bêtes séchées, matériel rare et coûteux à l’époque, ce qui conduisait les moines à réutiliser des pages déjà rédigées pour les réemployer.

Ils lavaient alors à grande eau ces feuilles de parchemin solides et épaisses pour faire disparaître les lignes écrites. Une fois séchées, ils recopiaient un autre texte. Cela pouvait se produire plusieurs fois au cours des siècles suivants. On appelle ces parchemins réutilisés des palimpsestes. Le fragment retrouvé en syriaque se trouvait donc effacé, sous un texte liturgique géorgien visible, et sous un texte grec d’un Père de l’Église, ces théologiens du premier millénaire, deuxième utilisation elle aussi éclipsée.

C’est par la photographie sous lumières ultraviolettes et multi-spectrale que ces trois textes, en trois langues, copiés successivement sur la même page, ont été rendus visibles. Ils sont ensuite devenus lisibles par un traitement numérique qui a séparé les types de phrases entremêlés, en délimitant trois versions grâce aux différences de formes de caractères des lettres.

La bibliothèque apostolique vaticane possède un laboratoire de premier plan en ce domaine. D’autres textes que l’on croyait perdus ont déjà été retrouvés avec la même technique au Vatican qui détient l’une des plus grandes collections de manuscrits du monde. Cette «découverte» annoncée comme telle par l’Académie autrichienne concerne donc un fragment qui avait déjà été repéré et étudié par la bibliothèque vaticane. Il ne met pas à jour un texte inconnu de l’Évangile puisque ce passage très classique est une traduction de texte rédigé en grec.

Voir également:

Reading the Negative: Kenneth Burke and Jean-Francois Lyotard on Augustine’s Confessions

Hanne Roer, University of Copenhagen

Abstract

This article offers a contrastive reading of Burke’s chapter on Augustine’s Confessions in The Rhetoric of Religion (1961) with Lyotard’s posthumous La Confession d’Augustin (1998). Burke’s chapter on Augustine throws new light on his logology, in particular its gendered character. Central to the interpretations of Burke and Lyotard is the notion of negativity that Burke explores in order to understand the human subject as a social actor, whereas Lyotard unfolds the radical non-identity of the writing subject.

Introduction

In this article I compare Kenneth Burke’s reading of Augustine’s Confessions in The Rhetoric of Religion (1961) to Jean-Francois Lyotard’s posthumous La Confession d’Augustin (1998, English 2000). The publication has attracted many readers because it offers new perspectives on Lyotard’s preoccupation with the philosophy and phenomenology of time. Understanding time is no simple matter as Augustine famously put it in the Confessions (book 11, 4):

- What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks me, I do not know. Yet I say with confidence that I know that if nothing passed away, there would be no past time; and if nothing were still coming, there would be no future time; and if there were nothing at all, there would be no present time. But, then, how is it that there are the two times, past and future, when even the past is now no longer and the future is now not yet?

This paradoxical circularity of time, the absence of presence, is central to Lyotard and also to Burke’s reading of the Confessions. It is inextricably connected to the notion of negativity, and I hope that my juxtaposition of Burke and Lyotard’s readings may clarify what the negative means to these two philosophers. My point is that although Burke’s reflections in The Rhetoric of Religion in many ways are related to and anticipating poststructuralism, his logology still presupposes some traditional assumptions, such as a gendered notion of the subject, that come to light in the comparison to Lyotard. Last but not least, Burke’s cluster reading of Augustine deserves more scholarly attention, often disappearing between the other parts of the work.

In the first part of The Rhetoric of Religion, “On Words and The Word, Burke defines his new metalinguistic project, logology, leading to the outlining of six analogies between language and theology. The second part, ”Chapter 2: Verbal Action in St. Augustine’s Confessions,” deals with Augustine’s Confessions, of which the last book (XIII) deals with beginnings and the interpretation of Genesis. Burke in the third part of The Rhetoric of Religion similarly proceeds to a reading of Genesis. It probably is unfair to concentrate on just one part of the work, since there might be a greater plan involved. According to Robert McMahon, Burke imitates the structure of Augustine’s Confessions, its upward movement towards the divine, ending with an exegesis of Genesis. Burke too goes from his reading of the Confessions to an interpretation of Genesis, but the last part of the book, “Prologue in Heavens” lends a comic frame to his ‘Augustinian’ enterprise (McMahon 1989). Rhetoricians, however, have focused mainly on the first part, the third chapter on Genesis and “Prologue in Heaven” (e.g. Barbara Biesecker 1994, Robert Wess 1996).

Scholars in the field of Augustinian studies have paid even less attention than rhetoricians to Burke’s reading. Thus Annemare Kotzé in her book Augustine’s Confessions: Communicative Purpose and Audience (2004) laments the lack of coherent, literary analyses of Augustine’s Confessions, one of the most read but least understood of all ancient texts (Kotzé 1). Today most scholars have given up the idea that the Confessions consists of a first autobiographical part, followed by a second philosophical part, arbitrarily put together by an Augustine who did not really know what he was doing! Kotzé does not mention Burke at all, as is often the case in scholarly works on Augustine.

Burke on Augustine’s Confessions

In the chapter on Augustine, Burke defines theology as ‘language about language’ (logology), words turning the non-existing into existence. The Confessions demonstrate this movement from word to Word, hence Augustine’s importance to Burke’s logological project: the study of the nature of language through the language of theology. Burke’s reading of the Confessions is essentially a commentary, following the dialectical moves of crucial pairs of oppositions (such as conversion/perversion) and comparing them to later authors such as Joyce, Shakespeare and Keats. It is not a literary analysis, in Kotzé’s sense, because Burke does not discuss the character of the authorial voice nor questions that the first half (books 1-9) of the Confessions is an autobiography (a modern idea, according to Kotzé).Burke is closer to literary analysis when it comes to the structure of the work. He focuses on the interplay between narrative and purely logical forms, as he calls it. His subtle reading points to the paradoxical circularity of Augustine’s work, working on many levels. The transcendent state of mind pondered upon books 10-13 is the result of the conversion, but it is also the condition allowing Augustine to write his story ten years after the event. The first and the second parts are stories about two different kinds of conversion. Book 8, the conversion scene in the garden, is the centre of the whole book and it has a counterpart in book 13, “the book of the Trinity,” where Monica’s maternal love is transformed into that of the Holy Spirit. This is, in Burke’s words, a dramatic tale, professed by a paradigmatic individual and addressed to God (and thus, one may add, not really an autobiography in the modern sense).

Another indication of the highly structured character of the Confessions is that the personal narrative in books 1-9 does not follow a chronological pattern but presents the events according to their “symbolic value,” in Burke’s words. This is the tension usually described by plot/story in narratology. For example, Burke notes, we are told that Monica dies before Adeodatus, but the scene describing Augustine’s last conversation with her and her death the following day comes after the information that Adeodatus has died.

Burke also demonstrates that the Confessions is tightly woven together by clusters of words forming their own associative networks. Burke’s cluster criticism is a kind of close reading, following the dialectical interplay between opposites. For example, in the Confessions, Burke observes, the word “open” (aperire) is central and knits the work together in a circle without beginning or end. Thus the work begins with the ”I” opening itself to God in a passionate invocation, the word “open” is also central to the moment of conversion in book 8 and, finally, it ends with these words: “It shall be opened.” Throughout the work “open” is used about important events, especially when the true meanings of the Scriptures open themselves to Augustine.

Verbum is another central term, not surprisingly, in the Confessions where Augustine transforms the rhetorical word into a theological Word. Burke claims that Augustine plays on the familiarity between the word verbum and a word meaning to strike (a verberando) when saying that God struck him with his Word (percussisti, p. 50). Verbum has several meanings in the Confessions: the spoken word, the word conceived in silence, the Word of God in the sense of doctrine and as Wisdom (second person of the Trinity). Burke also notes that Augustine links language with will (voluntas, velle), which is grounded in his conception of the Trinity. Burke thus recognises his own ideas about motivations in language in Augustine.

Another cluster of words and verbal cognates that form their own web of musical and semantic associations throughout the Confessions are the words with the root vert, such as: “adverse, diverse, reverse, perverse, eversion, avert, revert, advert, animadvert, universe, etc.” (Burke’s translations p. 63). These words abound in book 8 where God finally brings about the conversion of Augustine (conversisti enim ad te). The most important dialectical pair is conversion/perversion, which runs through all of the books. Book 8 is the dialectical antithesis of book 2: the two scenes – the perverse stealing of the pears and the conversion in the garden – are juxtaposed.

Burke also notices that the word for weight, pondus, is used in a negative sense in the beginning of the Confessions (the material weight of the body is what leads him away from God), but its sense is being converted until designating an upward drift in the last part of the book. This conversion of a single word is another evidence of Augustine thinking of language-as-action.

Burke concludes that the Confessions offer a double plot about two conversions – one formed by the narrator’s personal history, the other his intellectual transformation. In the last four books Augustine turns from the narrative of memories to the principles of Memory, a logological equivalent of the turn from “time” to “eternity,” Burke says (p. 123 ff). Memory (memoria) for Augustine is a category that subsumes mind (opposite modern uses of the word memory), thus his reflections on time and memory are also reflections on epistemology.

The Confessions are full of triadic patterns alluding to the Trinity, for example in Book XIII, xi where Augustine says that knowing, being and willing are inseparable. His road to conversion was triadic and involving the sacrifice of his material lusts, paralleling the sacrifice of Christ the Mediator: “And the Word took over his victimage, by becoming Mediator in the cathartic sense. In the role of willing sacrifice (a sacrifice done through love) the Second Person thus became infused with the motive of the Third Person (the term analogous to will or appetition, with corresponding problems). Similarly, just as Holy Spirit is pre-eminently identified with the idea of a “Gift,” so the sacrificial Son becomes a Gift sent by God. By this strategic arrangement, the world is “Christianized” at three strategic spots: The emergence of “time” out of “eternity” is through the Word as creative; present communication between “time” and “eternity” is maintained by the Word as Mediatory (in the Logos’ role as “Godman”); and the return from “time” back to “eternity” is through the Mediatory Godman in the role of sacrificial victim the fruits of Whose sacrifice the believer shares by believing in the teachings of the Word, as spread by the words of Scriptures and Churchmen” (pp. 167-8).

As a conclusion to his long analysis, Burke suggests that the clusters of terms (especially the vert-family) may be summed up in a single image (159), a god-term, that somehow is “another variant of the subtle and elusive relation between logical and temporal terminologies” (160). Burke also notices that Augustine in his search for spiritual perfection is on the way to delineate a new ecclesiastical hierarchy ready to replace the hierarchies of the Roman Empire.

The Frame: Logology and the Six Analogies Between Language and Theology

An explanation of the lack of interest among scholars in Burke’s reading of Augustine might be that in some ways it simply illustrates what he says about logology in the first part of The Rhetoric of Religion. The reading on Genesis in part Three, however, goes a step further ahead from the analogy between the philosophy of language and theology to the hierarchical aspects of language, the way language is constitutive of social order (Biesecker pp. 66-73). In this context I shall look closer at the first chapter, in order to understand Augustine’s role in the logological enterprise.

Augustine analysed the relation between the secular word and the Word of God, thus approaching the divine mystery through language, but Burke goes the opposite way. His logology is the study of theology as “pure” language, words without denotation, in order to understand how human beings signify through language. Logology is the successor to the dramatism of A Grammar of Motives (1945) and A Rhetoric of Motives (1950). Burke apparently grew more and more dissatisfied with the ‘positive dialectics’ inherent in dramatism and its reading strategy, the pentad, preventing him from writing the promised “A Symbolic of Motives.”1 Burke initially thought of dramatism as an ontology, a philosophy of human relations. These relations, similar to those between the persons in a drama, were thought of as determining human actions. Analysing these situations and the relations between the elements of the human drama would reveal the character of human motives.

However, having discovered the importance of the idea of negativity in philosophy and aesthetics, Burke became unsatisfied with dramatism conceived as ontology because this ignored the absence of meaning involved in language use. He studied the range of the meaning of negativity in philosophy and theology in three long articles from 1952-3 (reprinted in LSA, to which I refer). I shall look briefly at them because they are the forerunners of the logological project of The Rhetoric of Religion. In the first of these articles, Burke examines the notion of negativity in theology (Augustine, Bossuet), philosophy (Nietzsche, Bergson, Kant, Heidegger) and literature (Coleridge), leading to his own “logological” definitions, analyzing the role of the negative in symbolic action. He credits Bergson for the discovery of negativity as the basis of language but criticizes him for reducing it to the idea of Nothingness. The negative is primarily admonitory, the Decalogue being the perfect example of “Thou-shalt-nots” (LSA 422).

Burke produces a host of examples of the inherent negativity of our notions such as “freedom” (from what) and “victim” (seemingly the negation of guilt). There are formalist (negative propositions), scientist and anthropological ways of analysing the negative but the dramatistic focuses on the “”essential” instances of an admonitory or pedagogical negative.”

In the second article, Burke turns to Kant’s The Critique of Practical Reasoning. Burke sees Kant’s categorical imperative as a negative similar to the Decalogue. He also discusses the way the negative may be signified in literature, painting and music. An analysis of a sermon by Bossuet focuses on the interaction of positive images and negative ideas, linking it to Augustine’s “grand style” in De doctrina christiana. Behind moral advocacy and positive styles lies a negative without which great art has no meaning (453).

In the third article, Burke outlines a series of different kinds of negativity: the hortatory, the attitudinal, the propositional negative, the zero-negative (including ‘infinity’), the privative negative (blindness), the minus-negative (from debt and moral guilt) (459). From the original hortatory No language develops propositional negatives.

Now let us return to The Rhetoric of Religion in which Burke arranges these definitions into a new system, the logology replacing dramatism. The distinction between motion (natural) and act (determined by will) was a principal idea to dramatism and also to logology though Burke now discusses whether there are overlaps. He still claims that nothing in nature is negative, but exists positively, and hence language is what allows human beings to think in terms of negativity. Burke translates Augustine’s notion of eternity as God-given in contrast to sequential, human time into a distinction between logical and temporal patterns. This paradox between logical and narrative patterns is a leading principle of the logological project that seeks to explain the relation between the individual and social order, between free will and structural constraints.

Though the opposition between motion and act runs through all of Burke’s texts he now questions the clear boundary between them. In a similar way he questions his own analogy between words and the Word, hence his logology implies a deconstructive turn:

“So, if we could “analogize” by the logological transforming of terms from their “supernatural” reference into their possible use in a realm so wholly “natural” as that of language considered as a purely empirical phenomenon, such “analogizing” in this sense would really be a kind of “de-analogizing.” Or it would be, except that a new dimension really has been added” (8).

Burke thus nuances his former definition of language as referencing to everyday life and the natural world. As Biesecker puts it, there is an exchange between the natural and the supernatural taking place in language itself (56). Language is not just a system of symbols denoting objects or concepts because linguistic symbols create meaning by internal differences or similarities. Rhymes such as “tree, be, see, knee” form “associations wholly different from entities with which a tree is physically connected” (RR 9). What Burke observes here is what Saussure referred to as the arbitrariness of language or perhaps, more precisely, Roman Jakobson’s distinctive features. But is Burke’s logology based on theory of the sign? Again, we do not hear much about that, but there is a telling footnote in which Burke defines the symbol as a sign:

-

- A distinction between the thing tree (nonsymbolic) and the word for tree (a symbol) makes the cut at a different place. By the “symbolic” we have in mind that kind of distinction first of all. As regards “symbolic” in the other sense (the sense in which an object possesses motivational ingredients not intrinsic to it in its sheer materiality), even the things of nature can become “symbolic” (p. 9).

2Words are symbols that stand for things, a classical definition of the sign going back to Aristotle (who uses the term “symbolon” in De interpretatione) and Augustine (De doctrina christiana II). We may also note that Burke mostly talks about words, which at a first glance places him in this classical rhetorical tradition, in contrast to modern semiotics according to which the word is not the fundamental sign-unit. Burke is not primarily interested in linguistics but in the philosophy of language, i.e. theories concerning the relation between language and reality, meaning and language use. He warns against an empirical, “naturalistic” view of language that conceals the motivated character of language (p. 10). This shows his affinity to, on the one hand, the American pragmatic tradition of language philosophy (such as C. S. Peirce), and on the other, to reference and descriptivist theories of meaning. The latter is evident in his interest in naming, leading to his theory of title, entitlements and god-terms, terms that subsume classes of words.

Burke summarises these dialectics of theology in the six analogies between language and theology: The ‘words-Word’ analogy; the ‘Matter-Spirit’ analogy; the ‘Negative’ analogy; the ‘Titular’ analogy; the ‘Time-Eternity’ analogy; and the ‘Formal’ analogy. I shall shortly characterize these analogies in which the negative is the linking term, as Biesecker has argued (56-65).

1) The likeness between words about words and words about The Word: “our master analogy, the architectonic element from which all the other analogies could be deduced. In sum: What we say about words, in the empirical realm, will bear a notable likeness to what is said about God, in theology” (RR 13). Burke then defines four realms of reference for language: a) natural phenomena b) the socio-political sphere c) words and d) the supernatural, the ineffable. In a footnote he explains that language is empirically confined to referring to the first three realms, hence theology may show us how language can be stretched into almost transcending its nature as a symbol-system (p. 15). Hence the logologist should forget about the referential function and look at the linguistic operations that allow this exchange between words and the Word (cf. Biesecker 57).

2) Words are to non-verbal nature as Spirit is to Matter. By the second analogy, Burke emphasizes that the meaning of words are not material, though words have material aspects. As Burke puts it, there is a qualitative difference between the symbol and the symbolized. Biesecker (58) interprets the first two analogies this way: “If the purpose of the first two analogies is, at least in part, to calculate the force of linguistic or symbolic acts, to determine the kind of work they do by contemplating how they operate, the purpose of the third analogy is to try to account for such force by specifying its starting point.”

3) The third analogy concerns this starting point, the negative. Burke dismisses any naïve verbal realism (RR 17) and explains “the paradox of the negative: […] Quite as the word “tree” is verbal and the thing tree is non-verbal, so all words for the non-verbal must, be the very nature of the case, discuss the realm of the non-verbal in terms of what it is not. Hence, to use words properly, we must spontaneously have a feeling for the principle of the negative” (18).

Burke’s exposition of the ‘Negative’ analogy summarizes his reflections from the three articles mentioned above. Interestingly he interprets Bergson’s interest in propositional negatives as a symptom of “scientism” and prefers talking “dramatistically” about “the hortatory negative, “the idea of no” rather than the idea of the negative (20). Burke emphasizes that symbol-systems inevitably “transcend” nature being essentially different from the realm they symbolize. Analogies and metaphors only make sense because we understand what they do not mean. As Biesecker points out (58), the paradox of the negative governs all symbol systems and secures the ‘words-Word’ analogy that is the basis of logological operations. It is also the principle of the negative that produces the last three analogies.

4) The fourth analogy involves a movement upwards, the “via negativa” towards ever higher orders of generalizations. Whereas the third analogy concerned the correspondence between negativity in language and its place in negative theology, the fourth concerns the nature of language as a process of entitlement, leading in the secular realm towards an over-all title of title, this secular summarizing term that Burke calls a “god-term” (RR 25). Paradoxically this god-term is also a kind of emptying, and this doubled significance, in Biesecker’s words (60), is also central to the next analogy.

5) The fifth analogy: Time is to “eternity” as the particulars in the unfolding of a sentence’s unitary meaning. Burke is inspired by the passage in the Confessiones 4, 10, where Augustine ponders on signs: a sign does not mean anything before it has disappeared, giving room for a new sign. Burke finds an analogy between this linguistic phenomenon (the parts of the sentence signify retrospectively in the sequence of a sentence) and the theological distinction between time and eternity (27). For Augustine as well as Burke, meaning exceeds the temporal or diachronic series of signs through which it is communicated.

According to Biesecker, Burke’s Time-Eternity analogy reproduces the Appearance/Thing polarity so essential to Romantic idealism (62). Burke’s quote from Alice in Wonderland concerning the Cheshire cat’s smile tells us that the phenomenon is nothing in it self but “points to something [“smiliness”] in which meaning and being coincide.” Biesecker concludes: “… the movement of the argument implies the persistence rather than the undoing of a metaphysics of presence and the reaffirmation rather than the denigration of ontology, for what is being proposed here is that truth is accessible.” She does not agree with those have interpreted this passage as anticipating poststructuralism or Foucault. This priority of the essential receives support from the sixth analogy (Biesecker 63).

6) The sixth analogy concerns the relation between the thing and its name that really is a triadic relationship similar to “the design of the Trinity.” There is something between the thing and its name, a kind of knowledge (RR 29). Burke continues: “Quite as the first person of the Trinity is said to “generate the second, so the thing can be said to “generate” the word that names it, to call the word into being (in response to the thing’s primary reality, which calls for a name).” Burke next claims that there is a “There is a state of conformity, or communion, between the symbolized and the symbol” (30), an almost mystical realism that is not further explained, but supports Biesecker’s claim that this is a metaphysics of presence.

As a conclusion to his exposition of the six analogies, Burke says that they may help as conceptual instruments for shifting between “philosophical” and “narrative,” between temporal and logical sequences, hence enabling us to discuss “principles” or “beginnings” as variations of these styles (33). The new interpretative strategy, cluster criticism, is grounded in Burke’s preference for logical priority. Since temporal succession is secondary to logical structures, the task is now to discover “a detemporalized cycle of terms, a terminological necessity” (Melia quoted in Biesecker 66).

Lyotard on the Confession of Augustine

Burke characterizes his logology as a fragmentary, uncertain way of thinking, in opposition to a positivist thinking (RR 34). This certainly also holds for Lyotard’s way of reading, focusing on fissures and breaks in the text. Whereas Burke prioritizes the ‘logical’ patterns that so to say engender the narration, Lyotard, however, seeks to do away with this metaphysics of presence. The little book compiled after his death by his wife is a collection of fragments and thoughts, intended for a work on Augustine – as it is, it is “a book broken off” (Lyotard vii). The French text La confession d’Augustin consists of 20 fragments with these titles: Blason, Homme intérieur, Témoin, Coupure, Résistance, Distentio, Le sexuel, Consuetudo, Oubli, Temporiser, Immémorable, Diffèrend, Firmament, Auteur, Anges, Signes, Animus, Félure, Trance, Laudes (Blazon, The Inner Human, Witness, Cut, Resistance, Distentio, The Sexual, Consuetudo, Oblivion, Temporize, Immemorable, Differend, Firmament, Author, Angels, Signs, Animus, Fissure, Trance, Laudes). The Confession of Augustine unites two texts, the first 12 fragments are based on a lecture given October 1997, the last eight on a lecture given May 1997 and published under the title “The Skin of the Skies.” This is marked by a white page in the French text, but not in the English translation. The book also offers a last part, cahier/Notebook, containing collections of fragments and handwritten notes

Though Lyotard did not intend a publication as fragmented as it turned it out to be, the book is an example of Lyotard’s way of commenting sublime art. He interweaves quotations from the Confessions – particularly from the last four books on time and memory, also at centre of Lyotard’s own philosophy – with his own thoughts, creating a new persona, Augustine-Lyotard. In what follows I mostly quote the English text, but it should be remembered that there are differences, such as the choice of an old English translation of Augustine’s text. In this way the translation slightly differentiates between Augustine’s text and Lyotard’s commentary. Maria Muresan in her penetrating article, “Belated strokes: Lyotard’s writing of The Confession of Augustine,” points to the fact that Augustine also blends quotations from the Psalms without reference into his own text, a cut-up technique that Lyotard repeats in his reading (“the writing takes the form of a marginal gloss, which is a citation of the original text without quotations marks,” p. 155; Lyotard 85). These cuts are the effects of the stroke, the way the “I” in Confessions was struck by the divine word (percussisti, percuti, ursi), also noted by Burke. This original event is an absent cause, one that cannot be represented in language, but its effect is felt as a series of belated strokes, après-coups, a concept central to Lyotard, translating Freud’s Nachträglichkeit. These textual cuts perform a continued conversion, a process rather than a finite event (Muresan 152, 162).

Lyotard does not, as Burke, accept the narrative of Confessions locating the moment of confession to the scene in the garden (Tolle, lege) in book 8, but insists that Augustine’s work is an attempt at witnessing, not representing, a moment of conversion. Hence his book is called the “Confession d’Augustin,” in the singular instead of Augustine’s plural (ibid. 155). The words of Lyotard-Augustine intertwine in a co-penetration, a dramatic enactment of this conversion-experience, in which the “I” and “You” blend, the personae of Augustine’s work that imitate the ecstatic mode of the Psalms, the individual addressing his God, or rather his unknown, absent cause. Like Burke, Lyotard deconstructs the Christian theology, inverting the paradigm: “Lyotard discovered in the poetic parts of the Confessions the possibility of an inversed paradigm, namely verbalisation: instead of the Word made flesh, he found the possibility of the flesh made word […] what Lyotard reads in the Christian mystery is not primarily incarnation, the Word (the law, the concept) made flesh, but the opposite movement of the convulsion of flesh that liberates words, making itself word” (159).

Lyotard thus reverses the pattern between literature and theology, but his commentary is very different from Burke’s. He pays no attention to the narrative patterns but cuts out the lyrical, ecstatic passages (see his comment, Lyotard 67). He opens with this passage from Confessions 10, 27 that Burke also noted:

- Thou calledst and criest aloud to me; thou even breakedst open my deafness: thou shinest thine beams upon me, and hath put my blindness to flight: thou didst most fragrantly blow upon me, and I drew in my breath and I pant after thee; I tasted thee, and now do hunger and thirst after thee; thou didst touch me, and I even burn again to enjoy thy peace.

Lyotard’s commentary:

-

- Infatuated with earthly delights, wallowing in the poverty of satisfaction, the I was sitting idle, smug, like a becalmed boat in a null agitation. Then – but when? – you sweep down upon him and force entrance through his five estuaries. A destructive wind, a typhoon, you draw the closed lips of the flat sea toward you, you open them and turn them unfurling, inside out. Thus the lover excites the five mouths of the woman, swells her vowels, those of ear, of eye, of nose and tongue, and skin that stridulates. At present he is consumed by your fire, impatient for the return to peace that your fivefold ferocity brings him.Thine eye seekest us out, he protests, it piercest the lattice of our flesh, thou strokedst us with thy voice, we hasten on thy scent like lost saluki hounds. Thou art victorious; open-mouthed he gapes at your beatitude, you took him as a woman, cut him through, opened him, turned him inside out. Placing your outside within, you converted the most intimate part of him into his outside. And with this exteriority to himself, yours, an incision henceforth from within, you make your saints of saints,

penetrale meum

-

- , he confesses, thy shine in me. The flesh, forced five times, violated in its five senses, does not cry out, but chants, brings to each assault rhythm and rhyme, in a recitative, a

Sprechgesang

- . Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, invented the practice, from what Augustine says, for the Psalms to be read in this way, a modulation of respectful voices, in the same pitch of voice, to whose accents the community of Hebrews swayed (2-3).

Lyotard picks such passages from Confessions where the “I” tells us about being penetrated with God, feeling the terror accompanying the destruction of the subject, and the repercussions hereof in memory (most of the quotes are from Book X). Lyotard is exclusively interested in the intense aspects of Augustine’s religious experience that he finds expressed in the passages in which Augustine invokes his God or himself.

In the passage above and elsewhere in the text, Lyotard spells out the erotic connotations of Augustine’s words that occur particularly in his quotations from the Psalms. The first fragment has the title “Blazon,” a late medieval genre praising the parts of the female body, that Lyotard considers an inheritor to an ancient near-eastern tradition of love poetry. In Muresan’s words: “this erotic tradition was an intensive writing on the female body, whose beauty was located in a part of this body (sourcil, têtin, larme, bouche, oreille etc). […] In order to make visible this world of desire, the technique of the cut-out receives its full effect here: only parts of a body can make the writer write, and the reader love” (158). Whereas Burke tries to follow Augustine’s wish of controlling desire on the terms of the narrative, Lyotard goes the opposite way. When Burke notices that Augustine transfers his love for his mother to Continentia and the Holy Spirit, it is a subtle interpretation, relevant to the academic altercations about Augustine’s views on women and sex. Lyotard, on the other hand, does not take Augustine’s words for granted, but insists that the conversion-strokes are of an erotic character. Augustine does not transfer his desire into Continentia, rather he is transformed into a woman, a container of the divine (“the five holes”). Lyotard has not ‘given up’ Freud though he does not consider the Freudian unconscious a privileged source of the negative.3 Rather it is the belatedness (Nachträglichkeit) of the subjective experience that causes negativity, removing the origin into the unknown. The desire for God is related to the erotic urge: “ Two attractions, two twin appetites, almost equal in force, what does it take for one to prevail upon the other? A nuance, an accent, a child humming an old tune?” (Lyotard 22).

Lyotard reads Augustine’s conversion-stroke as a “Sprechgesang,” focusing on his rhythm, style and figures. The Confessions abound in figures combining metaphor and metonymy, such as “de manu linguae mea,” from the hand of my tongue. Read allegorically these figures express the sublimation of the physical into the spiritual, but they still convey a figural sensuality, alluding to the link between writing, beauty and desire. It is this ambiguity that Lyotard unfolds: “Receive here the sacrifice of my confessions, de manu linguae mea, from the hand of my tongue which thou hast formed and stirred up to confess unto thy name” (Confessions V I, cut into Lyotard’s fragment “Oblivion,” 26).

The belated stroke, the conversion-experience, is linked to beauty, being the aftermath of an a-temporal creative principle (Muresan 152). Augustine calls this process of creation pulchritudo (Divine beauty), in contrast to beautiful forms, species. Lyotard opens his commentary with the famous words from Confessions X 27: Sero te amavi, pulchritudo. Freud placed the artistic drive in the sexual desire, an expression of libidinal urges, and Lyotard agrees: “the feeling of Beauty and religion are both immanent movements of desire […] the illusory part of any transcendence” (Muresan 157).

Muresan’ emphasizes that Lyotard’s main interest in the Confessions are Augustine’s species and pulchritudo, both a-temporal principles creating time (163; see also Caputo 503-4). It is also an important observation that this pulchritudo is not identical to the Kantian sublime: “The sublime is a feeling opposing the senses’ interest (Kant), while Beauty-Pulchritudo is carried at the heart of this interest, which it actually endorses from the place of a surplus-value and a hyper-interest” (163). Beauty is a belated stroke, and writing is an act of recollecting the act, from memory. Beauty is the origin, a creating instant, a principium in which “God enjoyed this perfect coincidence of creation and the Word” (166).

Here as elsewhere, Lyotard comments on Augustine’s pair of opposites, distentio/intentio, the erring of the subject in earthly matters versus the urge for finding God, the conflict that the Confessions on the level of the narrative seems to dissolve. But the lyrical parts, according to Lyotard, reveals the act of writing is distensio, which is the constant companion of intentio. The confessive writing reveals a split subject, a subject penetrated by the other, and a product of time: “Dissidio, dissensio, dissipatio, distensio, despite wanting to say everything, the I infatuated with putting its life back together remains sundered, separated from itself. Subject of the confessive work, the first person author forgets that he is the work of writing. He is the work of time: he is waiting for himself to arrive, he believes he is enacting himself, he is catching himself up; he is, however, duped by the repeated deception that the sexual hatches, in the very gesture of writing, postponing the instant of presence for all times” (Lyotard 36).

The last fragments, from the lecture “The Skin of the Skies,” comment a passage from Confessions XIII xv in which Augustine envisions the firmament as covered by a tent, made by the skin that Adam and Eve had to wear after the Fall (Augustine’s interpretation of Isaiah xxxiv, 3-4). Though this eternal night is the punishment of Yahweh, the skin of the Heaven at the same time bears the Holy Scripture as inscription: the signs of bestiality have been transformed into the Holy Scripture.

Lyotard writes:

- Firmament. Is it not true that you dispensed the skin of the skies like a book? And who except you, O our God, made that firmament of the authority of the divine Scripture to be over us? For the sky shall be folded up like a book, and is even now stretched over us like a skin. […] The mantle of fur that you stretch out like a canopy over our heads is made from animal skin, the same clothing that our parents put on after they had sinned, the coverings of the exiled, with which to travel in the cold and the night of lost lives, sleepwalkers stumbling to their death (37).

This is the writing of God, the writing of the creator: “ Auctoritas is the faculty of growing, of founding, of instituting, of vouchsaving” (39). We are waiting for the divine to break through, knowing that without the protecting skin of the heaven it would crush us (40). We are reading the signs, the traces of the divine, but the confessive writing stems from a fissure, a stroke undermining the belief in the universal referents of sign systems. The writing intellect, the animus, tries in vain to understand itself.

This is far from the rhetoric of the law court, Lyotard notices: arguments, reasons, causes, the philosophical and rhetorical modes only presume to find light in the obscurity of signs (46). Still, the animus finds an escape in time and in memory making it possible to write its own story, not as a presentation of a reality but as a witness of this confession-experience. Surprisingly, perhaps, Lyotard’s La confession d’Augustin ends on a note of hope:

- What I am not yet, I am. Its short glow makes us dead to the night of our days. So hope threads a ray of fire in the black web of immanence. What is missing, the absolute, cuts its presence into the shallow furrow of its absence. The fissure that zigzags across the confession spreads with all speed over life, over lives. The end of the night forever begins” (57).

Burke’s and Lyotard’s Inverted Paradigms

Burke, too, comments briefly on this passage (158-9) in which he sees an exemplary mode of logological thinking, showing analogies between the secular and sacred realms: “In particular, logology would lay much store by Augustine’s chapter xv, in the “firmament of authority,” since it forms a perfect terministic bridge linking ideas of sky, Scriptures and ecclesiastical leadership” (159). In fact, Burke does not say much about this passage, contrary to Lyotard’s lengthy reflections on the writing of the creator, the mystical letters left for humans to decipher. Burke, on the other hand, twice emphasizes that this “the-world-is-a-book”-allegory legitimizes the church offering the authoritative exegesis of the obscure signs (158,159), something that Lyotard only briefly hints at. This, I believe, shows a major difference between these two readings of the Confessions. Burke is more interested in the social-hierarchical implications of the negativity of language than Lyotard (in this text, at least). They are both radical in their insistence upon the emptiness of origins, but whereas Lyotard deconstructs the notions of subject, form, narration, Burke is focused on the sociological implications, the links between subject and society, and his reading is also an ideological critique. Biesecker in her book takes up this suggestion and develops a critical logology combining Burke and Habermas’ philosophy of communication, a surprising combination at first sight, but the comparison of Burke with Lyotard’s reading also brings out this “sociological” aspect of logology.