Nul n’est prophète en son pays. Jésus

En ce moment, apparurent les doigts d’une main d’homme et ils écrivirent, en face du chandelier, sur la chaux de la muraille du palais royal (…) [Et] Daniel (…) [ayant] un esprit supérieur, de la science et de l’intelligence, la faculté d’interpréter les songes, d’expliquer les énigmes et de résoudre les questions difficiles (…) répondit en présence du roi: (…) Compté, compté, pesé et divisé. Daniel 5: 5-25

S’ils se taisent, les pierres crieront! Jésus (Luc 19 : 40)

Je te loue, Père, Seigneur du ciel et de la terre, de ce que tu as caché ces choses aux sages et aux intelligents, et de ce que tu les as révélées aux enfants. Jésus (Matthieu 11: 25)

Ne croyez pas que je sois venu apporter la paix sur la terre; je ne suis pas venu apporter la paix, mais l’épée. Car je suis venu mettre la division entre l’homme et son père, entre la fille et sa mère, entre la belle-fille et sa belle-mère; et l’homme aura pour ennemis les gens de sa maison. Jésus (Matthieu 10 : 34-36)

Vous entendrez parler de guerres et de bruits de guerres: gardez-vous d’être troublés, car il faut que ces choses arrivent. Mais ce ne sera pas encore la fin. Une nation s’élèvera contre une nation, et un royaume contre un royaume, et il y aura, en divers lieux, des famines et des tremblements de terre. Tout cela ne sera que le commencement des douleurs. Alors on vous livrera aux tourments, et l’on vous fera mourir; et vous serez haïs de toutes les nations, à cause de mon nom. Jésus (Matthieu 24: 6-9)

Nous prêchons la sagesse de Dieu, mystérieuse et cachée, que Dieu, avant les siècles, avait destinée pour notre gloire, sagesse qu’aucun des chefs de ce siècle n’a connue, car, s’ils l’eussent connue, ils n’auraient pas crucifié le Seigneur de gloire. Paul (1 Corinthiens 2, 6-8)

Il n’y a plus ni Juif ni Grec, il n’y a plus ni esclave ni libre, il n’y a plus ni homme ni femme; car tous vous êtes un en Jésus Christ. Paul (Galates 3: 28)

L’acte surréaliste le plus simple consiste, revolvers au poing, à descendre dans la rue et à tirer, au hasard, tant qu’on peut dans la foule. André Breton

Il faut avoir le courage de vouloir le mal et pour cela il faut commencer par rompre avec le comportement grossièrement humanitaire qui fait partie de l’héritage chrétien. (..) Nous sommes avec ceux qui tuent. Breton

Bien avant qu’un intellectuel nazi ait annoncé ‘quand j’entends le mot culture je sors mon revolver’, les poètes avaient proclamé leur dégoût pour cette saleté de culture et politiquement invité Barbares, Scythes, Nègres, Indiens, ô vous tous, à la piétiner. Hannah Arendt (1949)

Pourquoi l’avant-garde a-t-elle été fascinée par le meurtre et a fait des criminels ses héros , de Sade aux sœurs Papin, et de l’horreur ses délices, du supplice des Cent morceaux en Chine à l’apologie du crime rituel chez Bataille, alors que dans l’Ancien Monde, ces choses là étaient tenues en horreur? (…) Il en résulte que la fascination des surréalistes ne s’est jamais éteinte dans le petit milieu de l’ intelligentsia parisienne de mai 1968 au maoïsme des années 1970. De l’admiration de Michel Foucault pour ‘l’ermite de Neauphle-le-Château’ et pour la ‘révolution’ iranienne à… Jean Baudrillard et à son trouble devant les talibans, trois générations d’intellectuels ont été élevées au lait surréaliste. De là notre silence et notre embarras. Jean Clair

Nous avons offert des sacrifices humains à vos dieux du sport et de la télévision et ils ont répondu à nos prières. Terroriste palestinien (Jeux olympiques de Munich, 1972)

Que des cerveaux puissent réaliser quelque chose en un seul acte, dont nous en musique ne puissions même pas rêver, que des gens répètent comme des fous pendant dix années, totalement fanatiquement pour un seul concert, et puis meurent. C’est le plus grand acte artistique de tous les temps. Imaginez ce qui s’est produit là. Il y a des gens qui sont ainsi concentrés sur une exécution, et alors 5 000 personnes sont chassées dans l’Au-delà, en un seul moment. Ca, je ne pourrais le faire. A côté, nous ne sommes rien, nous les compositeurs… Imaginez ceci, que je puisse créer une oeuvre d’art maintenant et que vous tous soyez non seulement étonnés, mais que vous tombiez morts immédiatement, vous seriez morts et vous seriez nés à nouveau, parce que c’est tout simplement trop fou. Certains artistes essayent aussi de franchir les limites du possible ou de l’imaginable, pour nous réveiller, pour nous ouvrir un autre monde. Karlheinz Stockhausen (19.09. 01)

More ink equals more blood, newspaper coverage of terrorist incidents leads directly to more attacks. It’s a macabre example of win-win in what economists call a « common-interest game. Both the media and terrorists benefit from terrorist incidents. Terrorists get free publicity for themselves and their cause. The media, meanwhile, make money « as reports of terror attacks increase newspaper sales and the number of television viewers. Bruno S. Frey et Dominic Rohner

Come writers and critics who prophesize with your pen and keep your eyes wide the chance won’t come again and don’t speak too soon for the wheel’s still in spin and there’s no tellin’ who that it’s namin’. For the loser now will be later to win for the times they are a-changin’… Robert Zimmerman

And the people bowed and prayed To the neon god they made And the sign flashed out its warning In the words that it was forming and the sign said, « The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls and tenement halls » And whispered in the sounds of silence … Paul Simon

I tried very hard not to be influenced by him, and that was hard. ‘The Sound Of Silence’, which I wrote when I was 21, I never would have written it were it not for Bob Dylan. Never, he was the first guy to come along in a serious way that wasn’t a teen language song. I saw him as a major guy whose work I didn’t want to imitate in the least. Paul Simon

From the terrible opening line, in which darkness is addressed as “my old friend,” the lyrics of “The Sounds of Silence” sound like a vicious parody of a pompous and pretentious mid-’60s folk singer. But it’s no joke: While a rock band twangs aimlessly in the middle distance, Simon & Garfunkel thunder away in voices that suggest they’re scowling and wagging their fingers as they sing. The overall experience is like being lectured on the meaning of life by a jumped-up freshman. Worst Moment “Hear my words that I might teach you”: Officially the most self-important line in rock history! Blender magazine

Si l’expulsion de 1306 a pu faire l’objet d’une très discrète mention au titre de commémoration nationale en 2006, la présence juive dans la France médiévale est presque absente des synthèses historiques sur le Moyen Age. Du « Petit Lavisse » aux manuels scolaires des années 1980, le judaïsme médiéval n’appartient pas au « roman national », comme l’a montré l’historienne Suzanne Citron. (…) Les découvertes récentes signalent donc, comme par effraction, que les « archives du sol » recèlent les traces d’une histoire ignorée. La connaissance de la présence juive y gagne en profondeur : chaque site exhumé témoigne d’une terre où, au Moyen Age, les juifs ont vécu, produit, reçu, pensé, échangé mais aussi été persécutés et chassés. Laurence Sigal-Klagsbald et Paul Salmona

I think it’s just about the design. People may be aware of the English but they don’t know the deeper meaning or that it’s meant to be political. The word ‘Jesse’ is just cute. It’s nothing more serious than that. Korean trends mostly start in the country’s underground markets, where everything is on sale for about $10 and the quality isn’t so bad. Even foreign fast-fashion brands like Zara can be too expensive for Koreans, so teenage girls and 20-somethings tends to buy these cheaper underground brands. Han Yoo Ra

This truth of globalization is easier to see in these absurd examples, when something incongruous takes off, such as an old campaign T-shirt from a failed primary run. In this particular example, the “Jesse Jackson ’88” part of the T-shirt may have its origin in the annals of American history, but the shirt caught on because of its exalted position within the Korean casual fashion system. Jesse Jackson, or even America, has little to do with why Jesse Jackson ’88 campaign T-shirts are popular. Instead, it’s South Korea’s incredible cultural power that makes things cool in Asia — even American political nostalgia. Vox

Could it be that in these frighteningly uncertain times, a classic brand such as Levi’s feels reassuring? Historically, Levi’s was workwear. It stands for old-school tradition, but it also has ties with rebellion and counterculture; like Oreos and Oprah, it brings together both sides of the American political spectrum. It is cool without being pretentious, and widely available: John Lewis, Debenhams, Topman, Asos and Amazon all stock the classic Levi’s tee, as well as Levi’s shops themselves. It might also be that it serves as a substitute for the pricier/trendier Supreme box logo shirt, but at a pocket-patting £20. Advertising has probably played a part in its recent popularity, even if it feels as if this trend started on the street. In August last year, the company released Circles, an ad showing people from different cultures dancing, from Bhangra to hora, dabke to dancehall, with the tagline: “Men, women, young, old, rich, poor, straight, gay: let’s live how we dance.” With 22m views, it was one of the top 10 most-watched ads on YouTube in 2017. The Guardian

Mais pourquoi un tel succès pour un vêtement qui n’a rien de nouveau? Levi’s vend après tout des tee-shirts depuis des décennies. Une des raisons du succès pourrait être la prolifération qui s’auto-entraîne. Plus on en voit, plus on a envie d’en acheter. Un style vintage années 90, un prix relativement accessible pour un produit de marque alors qu’il faut compter minimum 80 euros pour un jean, et un mimétisme générationnel… Voilà quelques ingrédients de la recette miracle qui fait essaimer le tee-shirt Levi’s. Mais ce n’est peut-être pas le seul. Il semblerait en effet que Levi’s ait savamment orchestré ce buzz autour de la marque. Tout serait parti de trois photos postées par Kylie Jenner sur son compte Instagram en janvier 2016. La starlette américaine, d’ordinaire portée sur les tenues légères, y porte non pas un tee-shirt mais un simple jean vintage à l’étiquette rouge Levi’s bien mise en valeur. Trois simples photos, mais likées des millions des fois. « C’est ce qui a allumé le pétard, estime Laurent Thoumine, spécialiste de la mode chez Massive Details. Vu son nombre de followers (115 millions d’abonnés, l’un des plus gros comptes de la plateforme), ça a créé le buzz. » Et si Levi’s ne semble pas avoir rémunéré la starlette pour ce post, la marque a rapidement décidé de surfer sur le buzz. « Elle a commencé à demander à des influenceurs de poser avec le tee-shirt, très vite après le post de Kylie », explique Laurent Thoumine. Effectivement, si on remonte les posts Instagram qui sont légendées avec le hashtag #Levisshirt, on remarque que certains portent la mention « post sponsorisé » (« Werbung », en allemand, ci-dessous). Autrement dit, Levi’s a payé des influenceurs pour qu’ils portent son tee-shirt. Et pas n’importe lesquels: des « micro-influenceurs ». Plutôt que de miser sur des comptes au plus grand nombre d’abonnés possible, Levi’s s’est associé à des Instagrameurs qui comptent quelques centaines à quelques milliers d’abonnés. Ainsi, « la marque a capitalisé sur des personnes qui ont une réelle proximité avec leurs followers, donc une réelle influence sur eux », explique David Dubois, professeur de marketing à l’Insead. D’autant plus efficace que, avec le même budget que pour un seul post sponsorisé d’une star du réseau, « Levi’s a pu s’offrir des dizaines de milliers de posts », ajoute le spécialiste des campagnes sur les réseaux sociaux. Dans la foulée, la marque a lancé une nouvelle vidéo publicitaire à l’été 2017. Un carton: la pub qui met en scène des danseurs de tous horizons qui se déhanchent sur la chanson Makeba de la française Jain, a été vue plus de 25 millions de fois sur YouTube. Le tee-shirt Levi’s y fait une brève apparition mais le succès de la vidéo suffit à donner un lustre « cool » à la marque auprès des millenials. Et à mesure que les ventes de tee-shirts explosent, les contrefaçons ont rapidement fait leur apparition. Rien de plus facile à copier. Un tee-shirt blanc, un logo Levi’s et vous pouvez inonder le marché. « Une large proportion de ces tee-shirts sont des faux », assurent des spécialistes d’Accenture. Et leurs acheteurs, loin d’être dupes, seraient même séduits à l’idée de porter du logo faux. « Ils font écho à une sous culture du tee-shirt de marché portés sous une veste de marque lancée par des trend-setters comme les rappeurs PNL ou The Blaze », précise le consultant. Si c’est un manque à gagner pour Levi’s, la marque apprécie aussi d’avoir enfin réussi à séduire cette nouvelle génération. Au sommet à la fin des années 90 avec 7,1 milliards de dollars de ventes en 1996, la marque a été boudée par les jeunes de la génération suivante, ceux du début des années 2000. Cette « génération perdue » qui lui a préféré les jeans moins chers du japonais Uniqlo ou ceux de H&M a fait plonger Levi’s. En 2009, le chiffre d’affaires de la marque américaine avait fondu de plus de 40% par rapport au pic des années 90 à 4,1 milliards de dollars. Et si les ventes s’étaient stabilisées depuis, elles ont enfin bondi à 4,9 milliards de dollars en 2017, la plus forte croissance du groupe depuis 10 ans. Et avec des ventes attendues en hausse de 20% en 2018, vous n’êtes sans doute pas prêts d’arrêter d’en voir, des tee-shirts Levi’s. BFMtv

Dans un groupe de n individus, la tendance observée par l’individu numéro i à l’instant t dépend du poids de l’influence de chacun des autres membres du groupe sur lui (ce sont les Jij), mais également du type de hipsters présents (ils peuvent être plus ou moins modérés, ce qu’expriment les vecteurs sj) et du temps mis par le hipster i avant de réaliser que chacun des hipsters qui l’entoure est en train de commencer à lui ressembler sur tel ou tel point. La principale conclusion de l’étude est la suivante: seul le hipster qui parviendra à lire dans les pensées des autres hipsters afin d’avoir toujours un coup d’avance parviendra réellement à se démarquer. Les autres sont condamnés à rester les moutons qu’ils rêvent de ne pas être, allant tous dans la même direction à force de vouloir être uniques. Ce modèle mathématique complexe, Jonathan Touboul propose de le transposer au monde de la finance, arguant qu’un bon trader est un trader qui anticipe à la vitesse de la lumière, tandis que ses congénères plus lents prennent tous la même décision géniale au même moment, ce qui a pour effet de désamorcer les résultats de leur démarche. Pour finir, il imagine également un univers composé de hipsters et de non hipsters à parts égales: d’après son modèle, dans ce petit monde, chaque individu irait tour à tour et aléatoirement vers chaque tendance. Autrement dit, chaque sujet basculerait alternativement du mainstream au non-mainstream comme une boule de flipper, condamnant le monde des hipsters à faire bientôt tilt. Slate

Many observers have expressed concern for the excessive attention given to mass shooters of today and the deadliest of yesteryear. CNN’s Anderson Cooper has campaigned against naming names of mass shooters, and 147 criminologists, sociologists, psychologists and other human-behavior experts recently signed on to an open letter urging the media not to identify mass shooters or display their photos. While I appreciate the concern for name and visual identification of mass shooters for fear of inspiring copycats as well as to avoid insult to the memory of those they slaughtered, names and faces are not the problem. It is the excessive detail — too much information — about the killers, their writings, and their backgrounds that unnecessarily humanizes them. We come to know more about them — their interests and their disappointments — than we do about our next door neighbors. Too often the line is crossed between news reporting and celebrity watch. At the same time, we focus far too much on records. We constantly are reminded that some shooting is the largest in a particular state over a given number of years, as if that really matters. Would the massacre be any less tragic if it didn’t exceed the death toll of some prior incident? Moreover, we are treated to published lists of the largest mass shootings in modern US history. For whatever purpose we maintain records, they are there to be broken and can challenge a bitter and suicidal assailant to outgun his violent role models. Although the spirited advocacy of students around the country regarding gun control is to be applauded, we need to keep some perspective about the risk. Slogans like, “I want to go to my graduation, not to my grave,” are powerful, yet hyperbolic. James Alan Fox (Northeastern University)

En 2014 à l’aube d’une crise économique les Nouveaux Pères Fondateurs prennent le pouvoir aux États-Unis. Le Dr May Updale propose alors une idée : une Purge. Durant une période de douze heures consécutives toute activité criminelle est permise. Au cours de cette nuit chacun peut ainsi évacuer ses émotions négatives en se vengeant ou plus simplement en s’adonnant à la violence gratuite. Pour le Dr Updale c’est le moyen idéal d’évacuer la violence et la haine et donc de résoudre le problème de la criminalité durant le reste de l’année. En 2017, les Nouveaux Pères Fondateurs décident de tester l’idée. Une Purge est lancée sur l’île de Staten Island à New York sur la base du volontariat. Les habitants de l’île qui accepteront de rester chez eux durant la nuit seront payés et ceux qui sortiront commettre des meurtres toucheront un bonus. Cependant l’expérience est un échec, alors que des petits groupes tuent, la plupart des participants font la fête et commettent de simples délits. Les Nouveaux Pères Fondateurs décident alors, afin de contrer cet échec, d’envoyer un commando sur place pour tuer et permettre à l’expérience d’être un succès. Peu à peu le projet échappe au Dr Updale et les véritables intentions des Nouveaux Pères Fondateurs se révèlent. Wikipedia

La menace a été prise au sérieux. Depuis plusieurs jours, un appel à « la purge » visant les policiers circule sur les réseaux sociaux. Ce week-end, cette incitation à s’attaquer aux forces de l’ordre a gagné l’Essonne. Sur la publication bourrée de fautes d’orthographe appelant à « la purge de Corbeil-Essonnes », les auteurs demandent « de s’habiller en noir, avec un masque si possible ». La suite du message est une description précise du mode opératoire : « toutes les armes sont autorisées, brûlez tout ce que vous voyez, les forces de l’ordre devront être attaquées au mortier, feux d’artifice, pétards, pierres ». (…) Ce message, décliné dans différents lieux, « dépasse largement l’Essonne, précise le directeur départemental de la sécurité publique de l’Essonne, Jean-François Papineau. Nous recevons une grande vigilance sur l’ensemble du territoire relevant de la compétence de la Police nationale. Le Parisien

Il ne faut pas dissimuler que les institutions démocratiques développent à un très haut niveau le sentiment de l’envie dans le coeur humain. Ce n’est point tant parce qu’elle offrent à chacun les moyens de s’égaler aux autres, mais parce que ces moyens défaillent sans cesse à ceux qui les emploient. Les institutions démocratiques réveillent et flattent la passion de l’égalité sans pouvoir jamais la satisfaire entièrement. Cette égalité complète s’échappe tous les jours des mains du peuples au moment où il croit la saisir, et fuit, comme dit Pascal, d’une fuite éternelle; le peuple s’échauffe à la recherche de ce bien d’autant plus précieux qu’il est assez proche pour être connu et assez loin pour ne pas être goûté. Tout ce qui le dépasse par quelque endroit lui paraît un obstacle à ses désirs, et il n’y a pas de supériorité si légitime dont la vue ne fatigue sas yeux. Tocqueville

Il y a en effet une passion mâle et légitime pour l’égalité qui excite les hommes à vouloir être tous forts et estimés. Cette passion tend à élever les petits au rang des grands ; mais il se rencontre aussi dans le cœur humain un goût dépravé pour l’égalité, qui porte les faibles à vouloir attirer les forts à leur niveau, et qui réduit les hommes à préférer l’égalité dans la servitude à l’inégalité dans la liberté. Tocqueville

Les groupes n’aiment guère ceux qui vendent la mèche, surtout peut-être lorsque la transgression ou la trahison peut se réclamer de leurs valeurs les plus hautes. (…) L’apprenti sorcier qui prend le risque de s’intéresser à la sorcellerie indigène et à ses fétiches, au lieu d’aller chercher sous de lointains tropiques les charmes rassurants d’une magie exotique, doit s’attendre à voir se retourner contre lui la violence qu’il a déchaînée. Pierre Bourdieu

C’est une chose que Weber dit en passant dans son livre sur le judaïsme antique : on n’oublie toujours que le prophète sort du rang des prêtres ; le Grand Hérésiarque est un prophète qui va dire dans la rue ce qui se dit normalement dans l’univers des docteurs. Pierre Bourdieu

Des millions de Faisal Shahzad sont déstabilisés par un monde moderne qu’ils ne peuvent ni maîtriser ni rejeter. (…) Le jeune homme qui avait fait tous ses efforts pour acquérir la meilleure éducation que pouvait lui offrir l’Amérique avant de succomber à l’appel du jihad a fait place au plus atteint des schizophrènes. Les villes surpeuplées de l’Islam – de Karachi et Casablanca au Caire – et ces villes d’Europe et d’Amérique du Nord où la diaspora islamique est maintenant présente en force ont des multitudes incalculables d’hommes comme Faisal Shahzad. C’est une longue guerre crépusculaire, la lutte contre l’Islamisme radical. Nul vœu pieu, nulle stratégie de « gain des coeurs et des esprits », nulle grande campagne d’information n’en viendront facilement à bout. L’Amérique ne peut apaiser cette fureur accumulée. Ces hommes de nulle part – Shahzad Faisal, Malik Nidal Hasan, l’émir renégat né en Amérique Anwar Awlaki qui se terre actuellement au Yémen et ceux qui leur ressemblent – sont une race de combattants particulièrement dangereux dans ce nouveau genre de guerre. La modernité les attire et les ébranle à la fois. L’Amérique est tout en même temps l’objet de leurs rêves et le bouc émissaire sur lequel ils projettent leurs malignités les plus profondes. Fouad Ajami

La même force culturelle et spirituelle qui a joué un rôle si décisif dans la disparition du sacrifice humain est aujourd’hui en train de provoquer la disparition des rituels de sacrifice humain qui l’ont jadis remplacé. Tout cela semble être une bonne nouvelle, mais à condition que ceux qui comptaient sur ces ressources rituelles soient en mesure de les remplacer par des ressources religieuses durables d’un autre genre. Priver une société des ressources sacrificielles rudimentaires dont elle dépend sans lui proposer d’alternatives, c’est la plonger dans une crise qui la conduira presque certainement à la violence. Gil Bailie

Dans les années 80, pour se détendre et s’enthousiasmer, beaucoup d’étudiants se plongent dans l’oeuvre très accessible de René Girard. Sa théorie du mimétisme et du bouc émissaire fonctionne en tout et pour tout. Elle repose du marxisme et du structuralisme, ces occidents compliqués. Son auteur vit aux Etats-Unis, enseigne à l’université John Hopkins, puis à Stanford. Il a un goût d’ailleurs, explique le monde simplement, à partir de la violence. (…) Girard est foudroyé par sa théorie. Il applique à tout ce Meccano contorsionniste: aux écrivains (Dostoïevski, Proust, Kafka, Shakespeare), aux sociétés primitives (La violence et le sacré, 1972), à la Bible (aujourd’hui), au monde. Il en parle même à propos de l’anorexie galopante aux Etats-Unis: «La consommation est si facile que l’anticonsommation devient très forte, manière mimétique de dissimuler le mimétisme.» Le mimétisme est partout, y compris dans son contraire, telle une lèpre dont il faut se débarrasser. Son penseur fait songer à Toinette qui, dans le Malade imaginaire, ne cesse de répéter à son patient à tout propos: «Le poumon, vous dis-je! Le poumon!» Le passe-partout fait merveille. Il ouvre les portes d’un monde injuste et compliqué en le simplifiant » et donne la solution: l’Evangile! Le Christ en croix, cet ultime bouc émissaire, met à nu par son innocence et ses paraboles le mécanisme mimétique dont il faut sortir » par l’amour. (…) depuis les Etats-Unis où il vit le plus souvent, où il s’est marié et dont il a la nationalité, Girard révèle bien la vérité, en prophète, dans un style clair et martial. Il est d’ailleurs catholique depuis 1959: sa théorie naissante a fait de lui son premier disciple, puis son apôtre. A 76 ans, il a gardé la stature ferme d’un bonhomme biblique et, apparemment, ses certitudes; mais ce vieux santon de Provence, très élégant et armé de formidables sourcils, fait preuve d’une grande humilité dans son discours. (…) Après la guerre, diplômé de l’Ecole des chartes, il part, un peu par hasard, enseigner pour les Etats-Unis. Il a 25 ans et n’a presque rien lu des grands auteurs qu’il doit enseigner dans le fin fond de l’Indiana: «Je n’avais que quelques heures d’avance sur mes étudiants.» Il est viré car il ne publie pas. Il rejoint une petite université dans un Sud encore faulknerien, d’avant le mouvement des droits civiques. Ses amis américains assurent que ce passage au pays de la Bible et du fusil a marqué sa théorie de la violence. A l’époque, il est sartrien, et achète des Pléiade à 8,5 dollars pièce. Il se fait sa culture tout seul, (…) Girard, exilé, lointain, longtemps ignoré par une France structuraliste en diable, aime bien rappeler son personnage d’égaré, de prophète extérieur. (…) Pendant vingt ans, comme un demi-inconnu. En 1972, il critique la pensée de Claude Lévi-Strauss. En retour, silence presque partout. Est-il, comme dans sa théorie, une sorte de bouc émissaire tué par le non-débat? C’est ce qu’on dit alors, et c’est en partie faux. Girard, en vérité, est une sorte d’ovni. Il n’a pas fait ses classes dans le sérail. Il est tombé en France comme un virus non programmé. On ne le rejette pas, mais on ne l’assimile pas. Les grands penseurs du temps ont flairé le chrétien. Ils sont moins hostiles qu’interdits (…) Le succès populaire ne vient, comme souvent en France, qu’avec la polémique. En 1982, grâce au savoir-faire de son éditeur, Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde fait enfin scandale dans la presse. On traite Girard de mégalomane, de naïf. C’est le succès. Est-il enfin bouc émissaire bruyant? Il s’en amuse encore. Il a vieilli. Il est grand-père, aujourd’hui. Il va et vient entre ces deux pays, de colloques en maisons. Il regarde le feuilleton Seinfeld, «très mauvaise valeur, mais de grand talent», commet quelques anglicismes. L’américanisation de la France le stupéfie, lui qui se sent «si français, pour avoir vécu à l’étranger». Il écrit très lentement, se dégoûte courtoisement de ses livres, qu’il n’arrive pas toujours à finir comme il l’aurait voulu. Il regrette un peu les voyages transatlantiques en paquebot, aime relire Du côté de chez Swann, parce que «le coeur est là, à Combray, biblique». Sa phrase préférée est d’ailleurs tirée de la Bible: «Si nous avions vécu du temps de nos pères, nous ne nous serions pas joints à eux pour tuer les prophètes!» C’est une phrase qui le fait rire et trembler, tant elle montre la vanité des hommes, «toujours persuadés de faire mieux que les générations précédentes». Or, toutes les bergeries de Girard regorgent de boucs émissaires; et, s’il prêche la fin de cet enfer par l’évangile, il pense aussi que sa théorie «confine au cynisme». C’est un désespéré plein d’espoir et d’orgueil: un chrétien, en somme, à l’ancienne manière. Le premier titre auquel il avait songé, pour son nouveau livre, était: «Mes paroles ne passeront pas.» Une parole de Dieu, encore: «Le ciel et la terre passeront, mes paroles ne passeront pas.» Ni le diable ni Grasset n’en ont voulu. Vraiment trop penseur ex machina. Philippe Lançon

Je peux dire sans exagération que, pendant un demi-siècle, la seule institution française qui m’ait persuadé que je n’étais pas oublié en France, dans mon propre pays, en tant que chercheur et en tant que penseur, c’est l’Académie française. René Girard

Quand les riches s’habituent à leur richesse, la simple consommation ostentatoire perd de son attrait et les nouveaux riches se métamorphosent en anciens riches. Ils considèrent ce changement comme le summum du raffinement culturel et font de leur mieux pour le rendre aussi visible que la consommation qu’ils pratiquaient auparavant. C’est à ce moment-là qu’ils inventent la non-consommation ostentatoire, qui paraît, en surface, rompre avec l’attitude qu’elle supplante mais qui n’est, au fond, qu’une surenchère mimétique du même processus. Dans notre société la non-consommation ostentatoire est présente dans bien des domaines, dans l’habillement par exemple. Les jeans déchirés, le blouson trop large, le pantalon baggy, le refus de s’apprêter sont des formes de non-consommation ostentatoire. La lecture politiquement correcte de ce phénomène est que les jeunes gens riches se sentent coupables en raison de leur pouvoir d’achat supérieur ; ils désirent, si ce n’est être pauvres, du moins le paraitre. Cette interprétation est trop idéaliste. Le vrai but est une indifférence calculée à l’égard des vêtements, un rejet ostentatoire de l’ostentation. Le message est: « Je suis au-delà d’un certain type de consommation. Je cultive des plaisirs plus ésotériques que la foule. » S’abstenir volontairement de quelque chose, quoi que ce soit, est la démonstration ultime qu’on est supérieur à quelque chose et à ceux qui la convoitent. Plus nous sommes riches en fait, moins nous pouvons nous permettre de nous montrer grossièrement matérialistes car nous entrons dans une hiérarchie de jeux compétitifs qui deviennent toujours plus subtils à mesure que l’escalade progresse. A la fin, ce processus peut aboutir à un rejet total de la compétition, ce qui peut être, même si ce n’est pas toujours le cas, la plus intense des compétitions. (…) Ainsi, il existe des rivalités de renoncement plutôt que d’acquisition, de privation plutôt que de jouissance. (…) Dans toute société, la compétition peut assumer des formes paradoxales parce qu’elle peut contaminer les activités qui lui sont en principe les plus étrangères, en particulier le don. Dans le potlatch, comme dans notre société, la course au toujours moins peut se substituer à la course au toujours plus, et signifier en définitive la même chose. René Girard

Nous sommes encore proches de cette période des grandes expositions internationales qui regardait de façon utopique la mondialisation comme l’Exposition de Londres – la « Fameuse » dont parle Dostoievski, les expositions de Paris… Plus on s’approche de la vraie mondialisation plus on s’aperçoit que la non-différence ce n’est pas du tout la paix parmi les hommes mais ce peut être la rivalité mimétique la plus extravagante. On était encore dans cette idée selon laquelle on vivait dans le même monde: on n’est plus séparé par rien de ce qui séparait les hommes auparavant donc c’est forcément le paradis. Ce que voulait la Révolution française. Après la nuit du 4 août, plus de problème ! René Girard

L’inauguration majestueuse de l’ère « post-chrétienne » est une plaisanterie. Nous sommes dans un ultra-christianisme caricatural qui essaie d’échapper à l’orbite judéo-chrétienne en « radicalisant » le souci des victimes dans un sens antichrétien. (…) Jusqu’au nazisme, le judaïsme était la victime préférentielle de ce système de bouc émissaire. Le christianisme ne venait qu’en second lieu. Depuis l’Holocauste, en revanche, on n’ose plus s’en prendre au judaïsme, et le christianisme est promu au rang de bouc émissaire numéro un. René Girard

La soumission à l’Autre n’en est pas moins étroite lorsqu’elle prend des formes négatives. Le pantin n’est pas moins pantin lorsque les ficelles sont croisées. René Girard

L’erreur est toujours de raisonner dans les catégories de la « différence », alors que la racine de tous les conflits, c’est plutôt la « concurrence », la rivalité mimétique entre des êtres, des pays, des cultures. La concurrence, c’est-à-dire le désir d’imiter l’autre pour obtenir la même chose que lui, au besoin par la violence. Sans doute le terrorisme est-il lié à un monde « différent » du nôtre, mais ce qui suscite le terrorisme n’est pas dans cette « différence » qui l’éloigne le plus de nous et nous le rend inconcevable. Il est au contraire dans un désir exacerbé de convergence et de ressemblance. (…) Ce qui se vit aujourd’hui est une forme de rivalité mimétique à l’échelle planétaire. Lorsque j’ai lu les premiers documents de Ben Laden, constaté ses allusions aux bombes américaines tombées sur le Japon, je me suis senti d’emblée à un niveau qui est au-delà de l’islam, celui de la planète entière. Sous l’étiquette de l’islam, on trouve une volonté de rallier et de mobiliser tout un tiers-monde de frustrés et de victimes dans leurs rapports de rivalité mimétique avec l’Occident. Mais les tours détruites occupaient autant d’étrangers que d’Américains. Et par leur efficacité, par la sophistication des moyens employés, par la connaissance qu’ils avaient des Etats-Unis, par leurs conditions d’entraînement, les auteurs des attentats n’étaient-ils pas un peu américains ? On est en plein mimétisme.Ce sentiment n’est pas vrai des masses, mais des dirigeants. Sur le plan de la fortune personnelle, on sait qu’un homme comme Ben Laden n’a rien à envier à personne. Et combien de chefs de parti ou de faction sont dans cette situation intermédiaire, identique à la sienne. Regardez un Mirabeau au début de la Révolution française : il a un pied dans un camp et un pied dans l’autre, et il n’en vit que de manière plus aiguë son ressentiment. Aux Etats-Unis, des immigrés s’intègrent avec facilité, alors que d’autres, même si leur réussite est éclatante, vivent aussi dans un déchirement et un ressentiment permanents. Parce qu’ils sont ramenés à leur enfance, à des frustrations et des humiliations héritées du passé. Cette dimension est essentielle, en particulier chez des musulmans qui ont des traditions de fierté et un style de rapports individuels encore proche de la féodalité. (…) Cette concurrence mimétique, quand elle est malheureuse, ressort toujours, à un moment donné, sous une forme violente. A cet égard, c’est l’islam qui fournit aujourd’hui le ciment qu’on trouvait autrefois dans le marxisme. René Girard

By preaching against anorexia while keeping her own weight dangerously low, Isabelle Caro was telling her followers, « Take me as your guide, but don’t imitate me! » The paradox behind this type of mixed message was precisely diagnosed by Stanford’s René Girard, who names it the « mimetic double bind. » Since imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, anyone is happy to attract followers, but if they imitate too successfully, they soon become a threat to the very person they took as their model. No one likes to be beaten at their own game. Hence the contradictory message: « Do as I do… just don’t outdo me! » Imitation morphs imperceptibly into rivalry – this is Girard’s great insight, and he applies it brilliantly to competitive dieting. There’s no use searching for some mysterious, deep-seated psychological explanation, Girard writes: « The man in the street understands a truth that most specialists prefer not to confront. Our eating disorders are caused by our compulsive desire to lose weight. » We all want to lose weight because we know that’s what everyone else wants – and the more others succeed in shedding pounds, the more we feel the need to do so, too. Girard is not the first to highlight the imitative or mimetic dimension of eating disorders and their link to the fashion for being thin, but he emphasizes an aspect others miss: the built-in tendency to escalation that accompanies any fashion trend: « Everybody tries to outdo everybody else in the desired quality, here slenderness, and the weight regarded as most desirable in a young woman is bound to keep going down. » Mark Anspach

Le phénomène est déjà fabuleux en soi. Imaginez un peu : il suffit que vous me regardiez faire une série de gestes simples – remplir un verre d’eau, le porter à mes lèvres, boire -, pour que dans votre cerveau les mêmes zones s’allument, de la même façon que dans mon cerveau à moi, qui accomplis réellement l’action. C’est d’une importance fondamentale pour la psychologie. D’abord, cela rend compte du fait que vous m’avez identifié comme un être humain : si un bras de levier mécanique avait soulevé le verre, votre cerveau n’aurait pas bougé. Il a reflété ce que j’étais en train de faire uniquement parce que je suis humain. Ensuite, cela explique l’empathie. Comme vous comprenez ce que je fais, vous pouvez entrer en empathie avec moi. Vous vous dites : « S’il se sert de l’eau et qu’il boit, c’est qu’il a soif. » Vous comprenez mon intention, donc mon désir. Plus encore : que vous le vouliez ou pas, votre cerveau se met en état de vous faire faire la même chose, de vous donner la même envie. Si je baille, il est très probable que vos neurones miroir vont vous faire bailler – parce que ça n’entraîne aucune conséquence – et que vous allez rire avec moi si je ris, parce que l’empathie va vous y pousser. Cette disposition du cerveau à imiter ce qu’il voit faire explique ainsi l’apprentissage. Mais aussi… la rivalité. Car si ce qu’il voit faire consiste à s’approprier un objet, il souhaite immédiatement faire la même chose, et donc, il devient rival de celui qui s’est approprié l’objet avant lui ! (…) C’est la vérification expérimentale de la théorie du « désir mimétique » de René Girard ! Voilà une théorie basée au départ sur l’analyse de grands textes romanesques, émise par un chercheur en littérature comparée, qui trouve une confirmation neuroscientifique parfaitement objective, du vivant même de celui qui l’a conçue. Un cas unique dans l’histoire des sciences ! (…) Notre désir est toujours mimétique, c’est-à-dire inspiré par, ou copié sur, le désir de l’autre. L’autre me désigne l’objet de mon désir, il devient donc à la fois mon modèle et mon rival. De cette rivalité naît la violence, évacuée collectivement dans le sacré, par le biais de la victime émissaire. À partir de ces hypothèses, Girard et moi avons travaillé pendant des décennies à élargir le champ du désir mimétique à ses applications en psychologie et en psychiatrie. En 1981, dans Un mime nommé désir, je montrais que cette théorie permet de comprendre des phénomènes étranges tels que la possession – négative ou positive -, l’envoûtement, l’hystérie, l’hypnose… L’hypnotiseur, par exemple, en prenant possession, par la suggestion, du désir de l’autre, fait disparaître le moi, qui s’évanouit littéralement. Et surgit un nouveau moi, un nouveau désir qui est celui de l’hypnotiseur. (…) et ce qui est formidable, c’est que ce nouveau « moi » apparaît avec tous ses attributs : une nouvelle conscience, une nouvelle mémoire, un nouveau langage et des nouvelles sensations. Si l’hypnotiseur dit : « Il fait chaud » bien qu’il fasse frais, le nouveau moi prend ces sensations suggérées au pied de la lettre : il sent vraiment la chaleur et se déshabille. (…) On comprend que la théorie du désir mimétique ait suscité de nombreux détracteurs : difficile d’accepter que notre désir ne soit pas original, mais copié sur celui d’un autre. Pr Jean-Michel Oughourlian

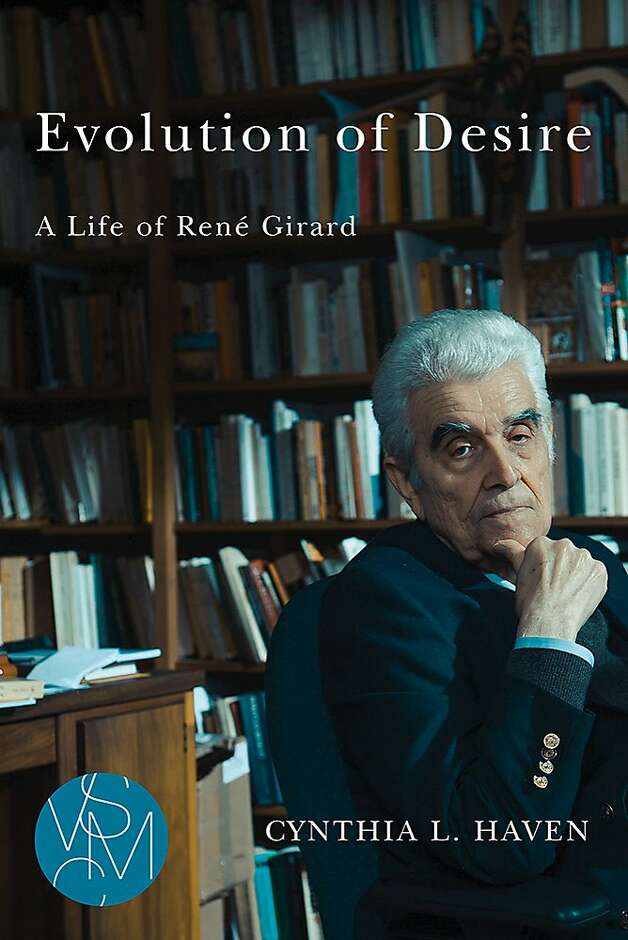

“Evolution of Desire” is the portrait of a provocative and engaging figure who was not afraid of pursuing his own line of inquiry. His legacy is not so much a grand theory as it is a flexible interpretive framework with useful social, cultural and historical applications. At a time when religious fundamentalism, violent extremism and societal division dominates the headlines, Haven’s book is a call to revisit and reclaim one of the 20th century’s most important thinkers. Rhys Trante

René Girard, who died three years ago, was a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science. His sprawling oeuvre might be called anthropological philosophy. His books make connections through theology, literary criticism, critical theory, anthropology, psychology, mythology, sociology, cultural studies, and philosophy. His core theory is that our human motivations are rooted in “mimetic desire”—a form of envy which is not simply desiring what another has, but also desiring to be like them. This competitive drive then sparks all other human conflict on both the micro- and macroscopic levels. He explained how mimetic desire leads us to blame others when our desire is frustrated, which then leads to blaming others and ultimately to the mechanism of scapegoating on the societal level, which forms the basis for ritual sacrifice. An accomplished academic, journalist, and author, Cynthia Haven was not only a colleague of Girard but also a close friend to him and his wife. Her biography is a warm, personal memoir while also providing an introduction to his thought and the historical context for the development of his ideas. (…) Brought up in a conventional French Catholic home, by the time he was at university he had adopted the fashionable atheism of the day. Witnessing the treatment of the Jews and the scapegoating of French collaborators in the aftermath of the Second World War no doubt had an impact on the development of Girard’s thought. The academic vigor and enthusiasm in postwar United States provided the perfect setting for a philosopher and historian who was constantly thinking outside the boundaries of strict academic territories. He would come to interact with the avant-garde writers and philosophers of his day—Camus, Sartre, Foucault, Derrida—and yet rise above them and their frequent rivalries and needy egos. In a world of narrowing academia, in which professors knew more and more about less and less, Girard was one who transcended the blinkered biases, the bureaucratic boundaries, and artificially defined territories. As T.S. Eliot’s entire life’s work must be understood through the lens of his 1927 conversion to Christianity, so I believe Girard is also best understood through his profound reversion to his Catholic faith. (…) Girard’s own awakening began in the winter of 1958-59 as he was working on his book about the novel. (…) His intellectual awareness was combined later with a series of profound mystical experiences as he rode on the train from Baltimore to Bryn Mawr. (…) A bit later he had a health scare which pushed the intellectual and the subjective mystical experiences into a firm commitment to religion. (…) For those who like to spot little signs of a providential plan, it might be noted that René Girard (also called Noël) who was born on Christmas Day, dated his conversion to March 25—the feast of the Annunciation—traditionally the date for the beginning of God’s redemptive work in the world, and in medieval times the date for the celebration of the New Year. Girard’s conversion and subsequent practice of his Catholic faith was an act of great courage. His huge leonine profile with his contemplative gaze grants him a kind of heroic stature that reflects the heroism of his witness. As post-modern academia drifted further and further into Marxist ideologies, fashionable atheism, and nihilistic post-structuralism, Girard was able to put forward an intellectual explication for age-old Christian themes using a fresh vocabulary and perspective. (…) What Girard did was to provide a fresh synthesis and applications of old truths within non-religious disciplines. He also re-vivified the concept of sacrifice, explaining its underlying dynamic rather than simply writing it off as a barbaric superstition. In an age where atheism is all the rage and all religions (especially Catholicism) are suspect, Girard does a great service in refreshing the language of the tribe and giving the intellectual universe a way of seeing old truths in a new way and new truths through an old lens. As a result, his work has already been hugely influential in a range of disciplines, both academic and cultural. (…) Ms. Haven is not much of a name-dropper, but when she describes, for example, The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man symposium held at John Hopkins in 1966, the pomposity of the whole affair is comedic. I sensed a touch of sarcasm as she reports the competing egos of famous French philosophers and the rivalry between intellectuals trying to see whose presentations can be the most incomprehensible, while they are also comparing notes on the luxury of their accommodations and the numbers of young women they are able to lure into philosophical discussions between the sheets. Dwight Longenecker

Girard’s mimetic theory— majestic in its simplicity, sweeping in its scope — has a way of gathering up stray anecdotes and incidents into its collective force, like a hurricane that swallows up every bit of moisture within range. Cynthia Haven’s Evolution of Desire offers the first of two long-awaited bibliographies of Girard (the other, which has the official sanction of the Girard family, is by Benoît Chantre). Rather than providing a biographer’s biography— full of footnotes, every stone overturned, weighty enough to ensure nobody else tries to write one — Haven has instead provided a portrait of sorts, bringing to life the Girard she came to know in the winter of his life. This is not to say that Evolution of Desire reads as a kind of “ last days and sayings ” of René Girard; Chantre has already provided that in Les derniers jours de René Girard (Grasset, 2016). Haven prefers the early Girard, providing remarkable insights into his childhood, and underscoring the importance of his birthplace, Avignon, for his intellectual development. Of his intellectual collaborators, Haven favors those from Girard’s first stint at Hopkins, rather than later figures. By doing so, she downplays the interactions between theological interlocutors like Raymund Schwager and James Alison, perhaps the most important current translator of mimetic theory into Christian theology. Schwager receives some attention, but Alison’s name does not grace the book. Even those familiar with the brazen and iconoclastic interdisciplinary style of Girard can forget what an autodidact he was. Girard’s training, both in France and in the United States, was in history. The École des Chartes formed students into librarians and archivists. From there Girard went to the United States, where his forgettable dissertation at the University of Indiana covered American opinions on France during the Second World War. When Girard came to literature in the 1950s and 60s, he did so as an outsider. And he continued this pattern of butting into adjacent fields, among them anthropology, ethnology, and eventually theology. Haven ’s recounting of Girard’s early years highlights the panache that would mark Girard. Whether as a prankster in school, or as the organizer of an exhibit that brought Picasso to Avignon in 1947 — this event initiated the world-renowned Avignon Festival — Girard displayed winning qualities before becoming an immortel in the Académie Française. For those who’ve tracked Girard for the past three decades, it is easy to start with Girard’s occupancy of the Hammond Chair at Stanford, beginning in 1981. Haven points out the importance of the earlier academic posts, especially his first stint at Johns Hopkins from 1957 – 68. There Girard made his reputation and also experienced a two-fold conversion, first with the help of great literature, and then through a cancer scare in 1959. During this period Girard published Deceit, Desire, and the Novel (1961) and rose to full professor, hardly an anticipated development given his failure to publish at Indiana. Girard enthusiasts know these details, mostly from his interview with James Williams at the end of The Girard Reader. Haven embellishes them through corroborating witnesses from these years. In perhaps the most enjoyable chapter, “The French Invasion,” she recalls Girard’s role in a monumental conference at Hopkins: “The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man.” This event marked the American emergence of Derrida, and decisively shifted Johns Hopkins as well as many other departments toward post-structuralism, or postmodernism. Although Girard had helped organize the conference, it led indirectly to his departure for Buffalo, as he could not bring himself to accept what he understood to be the anti-realist impulse of postmodern theory, which would become all the rage in literature departments. In his first stint at Hopkins, Girard became Girard. He trained his first graduate students there, including Andrew McKenna and Eric Gans. Girard also found important companions in Baltimore, including Richard Macksey, described as “a legendary polymath” (84), and a rising Dante scholar, John Freccero. Girard’s former chair at Hopkins, Nathan Edelman, recalls, “I thought of him as fearless. He had a tremendous self- confidence, in the best sense […] He never felt threatened by people who had different ideas […] We were enthralled by him. We desperately wanted his approval” (85). These sentiments arose well before Girard became a pied piper to Christian intellectuals. The strongest personal accusation from these years was that Girard could overgeneralize and dismiss too easily. (…) During these years Girard also met Jean-Michel Oughourlian, the first of many collaborators who would help Girard develop his distinctive interview-book. (…) Things Hidden signaled Girard’s coming out as a Christian, nearly twenty years after re-conversion in 1959. North Americans have developed a domesticated portrait of Girard: an interesting and important intellectual in the thrall of certain theologians. Yet in France, where the intellectual appetite is greater, Girard made an impact difficult to fathom. Haven notes that Things Hidden sold 35,000 copies in the first six months, which put it #2 on French non-fiction lists at the time. Eventually it sold 100,000 copies. That type of volume puts its somewhere between Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind in terms of immediate impact, and Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age or Alistair MacIntyre’s After Virtue, in terms of longevity. In France, if you had not read Things Hidden, you at least needed to fake it. Girard credited his publisher for the success, but Haven brings out Girard’s penchant for melding social critique with self-examination, which often produced the experience of realizing, while reading his books, that they were reading you. Haven describes Girard’s conversion and attends to his practice of Christianity, but does not make it the central thread of her biography. Although she relies on exchanges with friends of Girard, she pays less mind than some would to the encounter with Schwager, the Swiss Jesuit, despite the fact that their letters have recently been published and translated into English. Schwager first wrote Girard in 1974, and at that time saw what had only been a plan in Girard’s mind: the connection between the Bible and Girard’s theory of the sacred. When Schwager wrote Must There Be Scapegoats? , it actually appeared a few months prior to Things Hidden. As their letters make clear, despite a great debt to Girard, Schwager was an original thinker in his own right, and eventually helped Girard to change his mind about the relationship between sacrifice and Christianity. Haven credits Schwager with encouraging Girard’s desire to be theologically orthodox, although this had mixed results. By becoming a sort of defender of the Catholic faith, it “took him one large step farther away from fashionable intellectual circles and their feverish pursuit of novelty” (228). Haven also passes over The Scapegoat (1982), and I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (2001), which provide perhaps the richest sources for understanding Girard as a Christian thinker. This decision is somewhat remedied by Haven’s attention to Girard’s final major work, Battling to the End (2007). Haven was close to Girard at the time, and provides several first-hand anecdotes important for his readers. The pessimism and apocalyptic tone in the book really was Girard’s, and not Chantre’s. She also relays that Girard and Chantre had plans for an additional book on Paul. Although Battling to the End made a minor splash in the United States, it sold 20,000 copies in the first three months in France, was reviewed in all of the major newspapers, and was even cited by then-president Sarkozy. While Girard was in Paris, reporters waited outside his doorstep, whereas at Stanford, “Girard walked the campus virtually unnoticed and unrecognized” (254). Haven’s account focuses more on Girard than on the expansions of his influence. For many Girardians, the story of Girard’s intellectual journey should culminate in the Colloquium on Violence & Religion, founded in 1990 with Girard’s blessing, and faithfully attended by Girard until ill-health prevented him. The Colloquium continues to draw between one and two hundred attendees to its annual meeting. Although not all attendees are theologians or Christians, the attendees who work in literature tend to study figures like Tolkien, and many of the invited plenary speakers are major theologians or Christian intellectuals like Jean-Luc Marion or Charles Taylor. It will take some recalibration for these kinds of readers to understand that Girard’s interests cannot simply be distilled into a Christian apologetic, however subtly one might want to apply that term to Girard. Still, those invested in carrying on Girard’s legacy should welcome a book that traces Girard’s appeal so broadly. (…) The man claimed on more than one occasion that his theory sought to give Christianity and Christian theologians the anthropology that it deserved. Haven has provided a warm and magnanimous biography that Girard most certainly deserves. Grant Kaplan

On the occasion of the induction of the Franco-American intellectual René Girard (1923–2015) into the Académie Française in Paris in 2005, Girard articulated an abhorrence of what he called the modern descent into “the anti-Christian nihilism that has spread everywhere in our time.” One might well say that over a 60-year period, after his arrival from France as a graduate student at Indiana University in 1947, the literary critic and eventual anthropologist Girard found himself increasingly exposing, analyzing, and challenging this nihilism, and in fact progressively purging its residual effects in himself as a legatee of the histrionic, skeptical French literary-cultural tradition since the mid 18th century, deplored in the mid 19th century by Alexis de Tocqueville, one of whose chief facets Girard characterized as “decadent aestheticism.” Cynthia L. Haven’s outstanding new biographical and critical study, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, is a brilliant survey of his life and thought, but also a document of high importance for understanding what has happened to the conception and teaching of the humanities in the United States and elsewhere since the 1960s, and why Lionel Trilling was right to worry about “the uncertain future of humanistic education,” the title of a 1975 essay. (…) Girard in Mensonge romantique grants that competitive envy is the very social-psychological motor that drives “enlightened,” atheistic modern personal and social life. “At the heart of the book,” Cynthia Haven writes, “is our endless imitation of each other. Imitation is inescapable.” And she continues: “When it comes to metaphysical desire — which Girard describes as desires beyond simple needs and appetites — what we imitate is vital, and why.” We are inevitably afflicted with “mimetic desires,” first of parents and siblings, then of peers, rivals, and chosen role models, and these desires endlessly drive and agitate us, consciously and unconsciously, causing anxiety and “ontological sickness.” (…) Girard’s argument is that Rousseau’s ideal of completely autonomous personal authenticity, with its explosive social-political effects, is an initially alluring but ultimately and utterly false Narcissistic idol. Our free will is always (and always has been) constrained and conditioned, though not necessarily determined, by the very facts of human childhood, parenting, and linguistic, cognitive, conceptual, and cultural development (…) In 1958–59, before and while writing the “Romantic falsehood” volume, Girard went through internal, personal experiences corresponding to the implications of his own analysis of the “canker vice, envy,” and they amounted to an unexpected Christian conversion, about which Haven writes very well. Still nominally very much part of an atheistic, anti-foundational, French academic avant-garde in the United States, and now increasingly prominent in his position at Johns Hopkins, Girard was even one of the chief organizers of “The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man,” the enormously influential conference, in Baltimore in October 1966, that brought to America from France skeptical celebrity intellectuals including Jacques Lacan, Lucien Goldmann, Roland Barthes, and, most consequentially, the most agile of Nietzschean nihilists, Jacques Derrida, still obscure in 1966 (and always bamboozlingly obscurantist) but propelled to fame by the conference and his subsequent literary productivity and travels in America: another glamorous, revolutionary “Citizen Genet,” like the original Jacobin visitor of 1793–94. After this standing-room-only conference, Derrida and “deconstructionism,” left-wing Nietzscheanism in the high French intellectual mode, took America by storm, which is perhaps the crucial story in the subsequent unintelligibility, decline, and fall of the humanities in American universities, in terms both of enrollments and of course content. The long-term effect can be illustrated in declining enrollments: at Stanford, for example, in 2014 alone “humanities majors plummeted from 20 percent to 7 percent,” according to Ms. Haven. The Anglo-American liberal-humanistic curricular and didactic tradition of Matthew Arnold (defending “the old but true Socratic thesis of the interdependence of knowledge and virtue”), Columbia’s Arnoldian John Erskine (“The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent,” 1913), Chicago’s R. M. Hutchins and Mortimer Adler (the “Great Books”), and English figures such as Basil Willey (e.g., The English Moralists, 1964) and F. R. Leavis (e.g., The Living Principle: “English” as a Discipline of Thought, 1975) at Cambridge, and their successor there and at Boston University, Sir Christopher Ricks, was rapidly mocked, demoted, and defenestrated, with Stanford students eventually shouting, “Hey, hey, ho, ho! / Western civ has got to go!” The fundamental paradox of a relativistic but left-wing, Francophile Nietzscheanism married to a moralistic neo-Marxist analysis of cultural traditions and power structures — insane conjunction! — is now the very “gas we breathe” on university campuses throughout the West (…). Girard quietly repented his role in introducing what he later called “the French plague” to the United States, with Derrida, Foucault, and Paul DeMan exalting ludicrous irrationalism to spectacular new heights. His own efforts turned increasingly to anthropology and religious studies. Rousseau, Romantic primitivism, Nietzsche, and French aestheticism, diabolism (“flowers of evil”), and atheistic existentialism — Sade, Baudelaire, Gide, Sartre, Jean Genet, Foucault, Derrida, de Man, Bataille — had drowned the residually Christian, Platonist, Arnoldian liberal-humanistic tradition, which proved to be an unstable halfway house between religion and naturalism. Yet the repentant Girard resisted the deluge and critiqued it, initially from within (Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust), but increasingly relying on the longer and larger literary tradition, drawing particularly on Dante and Dostoyevsky as well as the Judaeo-Christian Scriptures. Like other close readers of Dostoyevsky, such as Berdyaev, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, other anti-Communist dissidents including Czesław Miłosz, Malcolm Muggeridge, and numerous Slavic scholars such as Joseph Frank, Girard came to see Dostoyevsky as the greatest social-psychological analyst of and antidote to the invidious “amour propre” and restless revolutionary resentments of modern life, themselves comprising and confirming an original sin of egotism and covetousness. Like Dostoyevsky, Girard became an increasingly orthodox Christian, seeing in the imitation of Christ the divinely appointed way out of the otherwise endless, invidious, simian hall-of-mirrors of “mimetic desires.” Girard argued that these competitive, comparative “mimetic desires” had geopolitical and not only personal and social effects, from the 18th century onward: siblings versus siblings, generations versus generations, nations versus nations (e.g., French versus Germans, 1789–1945, about which he wrote poignantly at the end of his life), cultures versus cultures (Islam versus the West today). (…) At Girard’s induction into the Académie Française in Paris in 2005, his fellow French Academician (and friend and Stanford colleague) Michel Serres also spoke and passionately deplored the violent and perverse world of contemporary audiovisual media, representing and exulting in human degradation “and multiplying it with a frenzy such that these repetitions return our culture to melancholic barbarism” and cause “huge” cultural “regression.” Rousseau’s idyllic Romantic dream has been transmogrified into Nietzsche’s exultant criminal vision of a world “beyond good and evil.” (…) Despite his enormous general audience and success in France, and the amazingly successful, disintegrative, Franco-Nietzschean “deconstructionist” invasion of American and British universities, publishing houses, and elite mentalities, he “marveled at the stability of the United States and its institutions,” Girard’s biographer tells. Let us hope Girard is right. Another Franco-American immigrant-intellectual of great integrity, intelligence, and influence, Jacques Barzun (1907–2012), wrote in his magisterial final work of cultural history, From Dawn to Decadence (2000), that modernism is “at once the mirror of disintegration and an incitement to extending it.” Cynthia Haven’s fine book on Girard is both brilliant cultural criticism and exquisite intellectual history, and an edifying biographical and ethical tale, providing a philosophical vision of a world beyond monkey-like mimicries and manias that demoralize, dispirit, and dehumanize the contemporary human person. It deserves wide notice and careful reading in a time of massive and pervasive attention-deficit disorder. M. D. Aeschliman

René Girard (1923- 2015) (…) is now the subject of a comprehensive biography by Cynthia Haven called “Evolution of Desire.” The title is apt. A key concept in Girard’s philosophy is what he called “mimetic desire.” All desire, he argued, is imitation of another person’s desire. Mimetic desire gives rise to rivalries and violence and eventually to the scapegoating of individuals and groups—a process that unites the community against an outsider and temporarily restores peace. Girard believes that the scapegoat mechanism has been intrinsic to civilization from its beginning to our own time. (…) Ms. Haven calls mimetic desire the linchpin of Girard’s work, equivalent to Freud’s fixation on sexuality and Marx’s focus on economics. In her discussion of Girard’s 1972 book “Violence and the Sacred,” she traces a trajectory from desire to conflict and ultimately to the scapegoating of entire groups. Think of the lynching of African-Americans, the systematic extinction of Jews in Nazi Germany, the murder of Christians in Muslim countries, and the current animus toward immigrants in Europe and America. Ms. Haven credits the French psychiatrist Jean-Michel Oughourlian with bringing Girard’s mimetic ideas into the social sciences. (…) When Mr. Oughourlian and Girard finally met in Paris, they experienced a mutual sympathy that led to collaboration on “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World,” first published in French in 1978. The title, taken from the Gospel of Matthew, reflected Girard’s increasing concern with Christianity, which he saw as a source for ending history’s perpetual cycles of violence. (…) Even as Girard negotiated the politics of American academe and international rivalries, he drew strength from his Catholic faith. Ms. Haven sympathetically recounts his conversion experiences in 1958 and 1959. At a time when atheism was practically de rigueur among French intellectuals, Girard came out not only as a believer but also as a spokesman for what he called the “truths of Christianity.” Among them, nonviolence headed the list, for he believed that Jesus, unlike earlier scapegoats and sacrificial victims, offered a path to lasting peace. Ms. Haven adds her own eloquent words: “The way to break the cycle of violent imitation is a process of imitatio Christi, imitating Christ’s renunciation of violence. Turn the other cheek, love one’s enemies and pray for those who persecute you, even unto death.” This message is as radical today as it was 2,000 years ago. Marilyn Yalom

Qules signes sur les murs de nos métros et de nos HLM ?

A l’heure où du plus dérisoire et du plus futile ….

Cette soudaine omniprésence savamment orchestrée de tee-shirts à la gloire de Levi’s sur nos plages et dans nos rues cet été …

Ou ce brusque hommage inconscient à la campagne de 1988 du pasteur américain Jessie Jackson dans les rues des métropoles coréennes et asiatiques …

Au plus grave et au plus inquiétant …

Cette véritable semaine en enfer de nouvelles lettres piégées aux domiciles des puissants …

Ou ces nouvelles fusillade ou tentative de fusillade dans les lieux de culte des plus faibles dans les communautés noire ou juive …

Pendant que du côté de Hollywood après nos anciennes avant-gardes et avant peut-être la réalité elle-même, on joue à « purger » par la violence son propre quartier …

Et que pour réussir son suicide, le premier dépressif venu peut entrainer avec lui une centaine d’nconnus …

Sans compter, entre une « fake news » et une commande de nouvelles appelant à l’assassinat de leur propre président, nos pompiers-pyromanes des médias …

Les signes, des murs de nos métros et HLM ou des vêtements ou comptes instagram de nos ados, sont littéralement partout …

Comme pouvait déjà nous le rappeler dès les années 60 le premier apprenti-prophète venu …

Ou aujourd’hui encore les modélisations et formules mathématiques de nos savants …

Tant de l’incroyable capacité d’imitation et de mimétisme de notre espèce humaine …

Que, montée aux extrêmes et mondialisation obligent, des conséquences potentiellement dévastatrices que celle-ci peut aussi avoir …

Comment ne pas s’étonner …

Qu’il ait fallu trois ans pour que sorte – et aux Etats-Unis seuls – la première biographie …

De ce nouveau Tocqueville qui sa vie durant en avait si magistralement démonté les mécanismes …

Et qui – péché capital des péchés capitaux – avait osé révéler les sources proprement bibliques de ses (re)découvertes ?

Mais comment surtout ne pas s’inquiéter …

Devant la colère qui gronde et qui monte des peuples irrémédiablement privés de leurs racines et de leurs identités …

De l’étrange cécité et surdité de nos dirigeants actuels …

Enfermés dans leur proprement suicidaire fuite en avant mondialisatrice ?

‘Evolution of Desire’ Review: Who Was René Girard?

A comprehensive new biography on the life of a French intellectual of international prominence who crossed the boundaries of literature, history, psychology, sociology, anthropology and religion.

René Girard (1923- 2015) was inducted into the French Academy in 2005. Many of us felt this honor was long overdue, given his international prominence as a French intellectual whose works had crossed the boundaries of literature, history, psychology, sociology, anthropology and religion. Today his theories continue to be debated among “Girardians” on both sides of the Atlantic. He is now the subject of a comprehensive biography by Cynthia Haven called “Evolution of Desire.”

The title is apt. A key concept in Girard’s philosophy is what he called “mimetic desire.” All desire, he argued, is imitation of another person’s desire. Mimetic desire gives rise to rivalries and violence and eventually to the scapegoating of individuals and groups—a process that unites the community against an outsider and temporarily restores peace. Girard believes that the scapegoat mechanism has been intrinsic to civilization from its beginning to our own time.

My personal acquaintance with René Girard began in 1957, when I entered Johns Hopkins as a graduate student in comparative literature at the same time that he arrived as a professor in the department of Romance languages. With his thick dark hair and leonine head, he was an imposing figure whose brilliance intimidated us all. Yet he proved to be generous and tolerant, even when I announced that I was to have another child—my third in five years of marriage.

Whatever his private feelings about maternal obligations—he and his wife, Martha, had children roughly the same age as ours—he always showed respect for my perseverance in the dual role of mother and scholar. Under his direction, I managed to finish my doctorate in 1963 and commenced a career as a professor of French.

Evolution of Desire

By Cynthia L. Haven

Michigan State, 317 pages, $29.95

Fast forward to 1981, when Girard came to Stanford University. I had been a member of the Stanford community for two decades, first through my husband, then on my own as a director of the Center for Research on Women. On campus, Girard quickly became a hallowed presence, a status he maintained long after his official retirement.

Among the people drawn into his life at Stanford was Ms. Haven, who formed a close friendship with Girard that eventually inspired her to write “Evolution of Desire.” Having already written books on the Nobel Prize-winning poets Czeslaw Milosz and Joseph Brodsky, Ms. Haven is no stranger to the challenges of presenting a great man’s life and ideas to the public. Her carefully researched biography is a fitting tribute to her late friend and one that will enlighten both specialists and non-specialists alike.

Ms. Haven rightly advises readers unfamiliar with Girard’s work to begin by reading his 1961 opus “Deceit, Desire, and the Novel.” This book demonstrates how the “romantic lie” underlying the belief in an autonomous self is punctured by the “fictional truth” found in such writers as Cervantes, Stendhal, Flaubert, Dostoevsky and Proust. In their novels, the protagonist comes to realize that his dominating passion is what Girard alternately calls “mimetic,” “mediated” or “metaphysical.” The fictive hero’s mimetic desire leads to social conflict and personal despair until he renounces the romantic lie and seeks some form of self-transcendence. Readers of Proust may remember Swann’s ultimate reflection: “To think that I ruined years of my life . . . for a woman who wasn’t even my type.”

Ms. Haven calls mimetic desire the linchpin of Girard’s work, equivalent to Freud’s fixation on sexuality and Marx’s focus on economics. In her discussion of Girard’s 1972 book “Violence and the Sacred,” she traces a trajectory from desire to conflict and ultimately to the scapegoating of entire groups. Think of the lynching of African-Americans, the systematic extinction of Jews in Nazi Germany, the murder of Christians in Muslim countries, and the current animus toward immigrants in Europe and America.

Ms. Haven credits the French psychiatrist Jean-Michel Oughourlian with bringing Girard’s mimetic ideas into the social sciences. She relates the amusing story of how Mr. Oughourlian crossed the Atlantic impulsively in 1973 so as to find the author of “Violence and the Sacred” in New York. He was dismayed to discover that Girard was not in New York City but in far-away Buffalo at the State University of New York, where the former Hopkins professor of French had accepted a position in the English Department. When Mr. Oughourlian and Girard finally met in Paris, they experienced a mutual sympathy that led to collaboration on “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World,” first published in French in 1978. The title, taken from the Gospel of Matthew, reflected Girard’s increasing concern with Christianity, which he saw as a source for ending history’s perpetual cycles of violence.

Ms. Haven’s ability to interweave Girard’s life with his publications keeps her narrative flowing at a lively pace. For a man who woke every day at 3:30 a.m. and wrote until his professorial duties took over, it would be enough for any biographer to focus on his intellectual life, without linking his thoughts to a person ambulating in the world. Fortunately, Ms. Haven portrays Girard as he interacted with colleagues, students, friends and family.

The list of his close associates throughout his long career at Hopkins, Buffalo and Stanford is impressive. It includes such distinguished scholars and critics as John Freccero, Richard Macksey, Eugenio Donato, Jean-Pierre Dupuy, Michel Serres, Hans Gumbrecht and Robert Harrison. A complete list would run close to 40 or 50 men.

Yes, all men. I can’t refrain from noting the exclusively male nature of Girard’s intellectual network, as well as the predominance of men in competing movements, like structuralism and deconstructionism. The chapter Ms. Haven devotes to a major conference organized by Girard and his Hopkins associates in 1966 reads like an uproarious movie script featuring the oversize egos of the all-male cast, most notably the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

Even as Girard negotiated the politics of American academe and international rivalries, he drew strength from his Catholic faith. Ms. Haven sympathetically recounts his conversion experiences in 1958 and 1959. At a time when atheism was practically de rigueur among French intellectuals, Girard came out not only as a believer but also as a spokesman for what he called the “truths of Christianity.” Among them, nonviolence headed the list, for he believed that Jesus, unlike earlier scapegoats and sacrificial victims, offered a path to lasting peace. Ms. Haven adds her own eloquent words: “The way to break the cycle of violent imitation is a process of imitatio Christi, imitating Christ’s renunciation of violence. Turn the other cheek, love one’s enemies and pray for those who persecute you, even unto death.” This message is as radical today as it was 2,000 years ago.

—Ms. Yalom is a senior scholar at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University. Her most recent book is “The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love.”

Mimicry, Mania, and Memory: René Girard Remembered

In a new biography of the anthropologist and literary critic, we glimpse the personal experiences that corresponded to his analysis of competitive envy. Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, by Cynthia L. Haven (Michigan State University Press, 346 pages, $29.95)

On the occasion of the induction of the Franco-American intellectual René Girard (1923–2015) into the Académie Française in Paris in 2005, Girard articulated an abhorrence of what he called the modern descent into “the anti-Christian nihilism that has spread everywhere in our time.” One might well say that over a 60-year period, after his arrival from France as a graduate student at Indiana University in 1947, the literary critic and eventual anthropologist Girard found himself increasingly exposing, analyzing, and challenging this nihilism, and in fact progressively purging its residual effects in himself as a legatee of the histrionic, skeptical French literary-cultural tradition since the mid 18th century, deplored in the mid 19th century by Alexis de Tocqueville, one of whose chief facets Girard characterized as “decadent aestheticism.”

Cynthia L. Haven’s outstanding new biographical and critical study, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, is a brilliant survey of his life and thought, but also a document of high importance for understanding what has happened to the conception and teaching of the humanities in the United States and elsewhere since the 1960s, and why Lionel Trilling was right to worry about “the uncertain future of humanistic education,” the title of a 1975 essay. Starting out as a literary critic writing mainly about the 19th-century novel, Girard developed into a wide-ranging cultural critic and anthropologist at Johns Hopkins (1957–68, 1976–80) and then at Stanford (1981–2015). His thinking has had a vast effect throughout the Western world on literary studies, anthropology, sociology, religious studies, theology, and even the writing of history, influencing numerous scholars in these fields, as well as novelists (Milan Kundera, J. M. Coetzee), and leading to associations and journals for the study and application of his thought. Evolution of Desire is itself a distinguished, judicious work of interdisciplinary cultural analysis and synthesis in the current of Girard.

Most of Girard’s books were published first in French in France, some of them best-sellers, leading ultimately to his election to the Académie Française. The first, Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque (1961; with a pun on “roman,” which also means the novel) was translated into English and published as Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure (1965), and it introduced the theme, which he called “mimetic desire,” that would make Girard famous and influential in the world of the humanities.