La France ne peut plus être un pays d’immigration, elle n’est pas en mesure d’accueillir de nouveaux immigrants (…) Le regroupement familial pose par son ampleur des problèmes très réels de logement, de scolarisation et d’encadrement social. (…) On ne peut tolérer que des clandestins puissent rester en France. (…) Il faut tout mettre en œuvre pour que les décisions de reconduite à la frontière soient effectives (…) La très grande majorité des dossiers déposés à l’Ofpra s’avère injustifiée (de l’ordre de 90 %), ces demandes n’étant qu’un prétexte pour bénéficier des avantages sociaux français (…) Les élus peuvent intervenir efficacement et les collectivités locales […] doivent avoir leur mot à dire quant au nombre d’immigrés qu’elles accueillent sur leur territoire », afin de « tenir compte du seuil de tolérance qui existe dans chaque immeuble (…) Les cours de “langues et cultures des pays d’origine” doivent être facultatifs et déplacés en dehors des horaires scolaires. (….) l’islam n’apparaît pas conforme à nos fondements sociaux et semble incompatible avec le droit français (…) Il y a bien incompatibilité entre l’islam et nos lois. C’est à l’islam et à lui seul de [s’adapter] afin d’être compatible avec nos règles. (…) ce n’est pas aux pouvoirs publics d’organiser l’islam. On n’intègre pas des communautés mais des individus (…) Il convient de s’opposer (…) à toute tentative communautaire qui viserait à instaurer sur le sol français des statuts personnels propres à certaines communautés. (…) Les activités cultuelles doivent être exclues de la compétence des associations relevant de la loi de 1901. (…) la mainmise de l’étranger sur certaines de ces associations est tout à fait inacceptable. (…) la création de lieux de culte doit se faire dans le respect (…) du patrimoine architectural de la France. Etats généraux RPR-UDF (1er avril 1990)

At that point, you’ve got Europe and a number of Gulf countries who despise Qaddafi, or are concerned on a humanitarian basis, who are calling for action. But what has been a habit over the last several decades in these circumstances is people pushing us to act but then showing an unwillingness to put any skin in the game. (…) Free riders (…) So what I said at that point was, we should act as part of an international coalition. But because this is not at the core of our interests, we need to get a UN mandate; we need Europeans and Gulf countries to be actively involved in the coalition; we will apply the military capabilities that are unique to us, but we expect others to carry their weight. Obama (2016)

Trump’s approval rating trajectory has diverged from past presidents. Trump’s approval rating has actually ticked up as the 2018 midterm elections approach. The Hill

Nous protégeons l’Allemagne, la France et tout le monde et nous payons beaucoup d’argent pour ça… Ça dure depuis des décennies mais je dois m’en occuper parce que c’est très injuste pour notre pays et pour nos contribuables. Nous sommes censés vous défendre contre la Russie alors pourquoi payez-vous des milliards de dollars à la Russie pour l’énergie ! En fait l’Allemagne est captive de la Russie. Donald Trump

Quand le Mexique nous envoie ces gens, ils n’envoient pas les meilleurs d’entre eux. Ils apportent des drogues. Ils apportent le crime. Ce sont des violeurs. Donald Trump

Ce que je dis – et j’ai beaucoup de respect pour les Mexicains. J’aime les Mexicains. J’ai beaucoup de Mexicains qui travaillent pour moi et ils sont géniaux. Mais nous parlons ici d’un gouvernement beaucoup plus intelligent que notre gouvernement. Beaucoup plus malin, plus rusé que notre gouvernement, et ils envoient des gens. Et ils envoient – si vous vous souvenez, il y a des années, quand Castro a ouvert ses prisons et il les a envoyés partout aux États-Unis (…) Et vous savez, ce sont les nombreux repris de justice endurcis qu’il a envoyés. Et, vous savez, c’était il y a longtemps, mais (…) à titre d’exemple, cet horrible gars qui a tué une belle femme à San Francisco. Le Mexique ne le veut pas. Alors ils l’envoient. Comment pensez-vous qu’il est arrivé ici cinq fois? Ils le chassent. Ils déversent leurs problèmes sur États-Unis et nous n’en parlons pas parce que nos politiciens sont stupides. (…) Et je vais vous dire quelque chose: la jeune femme qui a été tuée – c’était une statistique. Ce n’était même pas une histoire. Ma femme me l’a rapporté. Elle a dit, vous savez, elle a vu ce petit article sur la jeune femme de San Francisco qui a été tuée, et j’ai fait des recherches et j’ai découvert qu’elle a été tuée par cet animal … qui est venu illégalement dans le pays plusieurs fois et qui d’ailleurs a une longue liste de condamnations. Et je l’ai rendu public et maintenant c’est la plus grande histoire du monde en ce moment. … Sa vie sera très importante pour de nombreuses raisons, mais l’une d’entre elles sera de jeter de la lumière et de faire la lumière sur ce qui se passe dans ce pays. Donald Trump

Ou vous avez des frontières ou vous n’avez pas de frontières. Maintenant, cela ne signifie pas que vous ne pouvez pas permettre à quelqu’un de vraiment bien devenir citoyen. Mais je pense qu’une partie du problème de ce pays est que nous accueillons des gens qui, dans certains cas, sont bons et, dans certains cas, ne sont pas bons et, dans certains cas, sont des criminels. Je me souviens, il y a des années, que Castro envoyait le pire qu’il avait dans ce pays. Il envoyait des criminels dans ce pays, et nous l’avons fait avec d’autres pays où ils nous utilisent comme dépotoir. Et franchement, le fait que nous permettons que cela se produise est ce qui fait vraiment du mal à notre pays. Donald Trump

I was in primary school in my native Colombia when my father was murdered. I was six – just one year older than my daughter is now. My father was an officer in the Colombian army at a time when wearing a uniform made you a target for narcoterrorists, Farc fighters and guerrilla groups. What I remember clearly from those early years is the bombing and the terror. I was so afraid, especially after my dad died. At night, I would curl up in my mother’s bed while she held me close. She could not promise me that everything was going to be all right, because it wasn’t true. I don’t want my daughter to grow up like that. But when I turn on my TV, I see terrorist attacks in San Bernardino and in Orlando. There are dangerous people coming across our borders. Trump was right. Some are rapists and criminals, but some are good people, too. But how do we know who is who, when you come here illegally? I moved to the US in 2006 on a work permit. It took nearly five years and thousands of dollars to become a US citizen. I know the process is not perfect, but it’s the law. Why would I want illegals coming in when I had to go through this? It’s not fair that they’re allowed to jump the line and take advantage of so many benefits, ones that I pay for with my tax dollars. People assume that because I’m a woman, I should vote for the woman; or that because I’m Latina, I should vote for the Democrat. The Democrats have been pandering to minorities and women for the last 50 years. They treat Latinos as if we’re all one big group. I’m Colombian – I don’t like Mariachi music. Donald Trump is not just saying what he thinks people want to hear, he’s saying what they’re afraid to say. I believe that he’s the only candidate who can make America strong and safe again. Ximena Barreto (31, San Diego, California)

This week, as President Trump comes out in support of a bill that seeks to halve legal immigration to the United States, his administration is emphasizing the idea that Americans and their jobs need to be protected from all newcomers—undocumented and documented. To support that idea, his senior policy adviser Stephen Miller has turned to a moment in American history that is often referenced by those who support curbing immigration: the Mariel boatlift of 1980. But, in fact, much of the conventional wisdom about that episode is based on falsehoods rooted in Cold War rhetoric. During a press briefing on Wednesday, journalist Glenn Thrush asked Miller to provide statistics showing the correlation between the presence of low-skill immigrants and decreased wages for U.S.-born and naturalized workers. In response, Miller noted the findings of a recent study by Harvard economist George Borjas on the Mariel boatlift, which contentiously argued that the influx of over 125,000 Cubans who entered the United States from April to October of 1980 decreased wages for southern Florida’s less educated workers. Borjas’ study, which challenged an earlier influential study by Berkeley economist David Card, has received major criticisms. A lively debate persists among economists about the study’s methods, limited sample size and interpretation of the region’s racial categories—but Miller’s conjuring of Mariel is contentious on its own merits. The Mariel boatlift is an outlier in the pages of U.S. immigration history because it was, at its core, a result of Cold War posturing between the United States and Cuba. Fidel Castro found himself in a precarious situation in April 1980 when thousands of Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy seeking asylum. Castro opened up the port of Mariel and claimed he would let anyone who wanted to leave Cuba to do so. Across the Florida Straits, the United States especially prioritized receiving people who fled communist regimes as a Cold War imperative. Because the newly minted Refugee Act had just been enacted—largely to address the longstanding bias that favored people fleeing communism—the Marielitos were admitted under an ambiguous, emergency-based designation: “Cuban-Haitian entrant (status pending).” (…) In order to save face, Castro put forward the narrative that the Cubans who sought to leave the island were the dregs of society and counter-revolutionaries who needed to be purged because they could never prove productive to the nation. This sentiment, along with reports that he had opened his jails and mental institutes as part of this boatlift, fueled a mythology that the Marielitos were a criminal, violent, sexually deviant and altogether “undesirable” demographic. In reality, more than 80% of the Marielitos had no criminal past, even in a nation where “criminality” could include acts antithetical to the revolutionary government’s ideals. In addition to roughly 1,500 mentally and physically disabled people, this wave of Cubans included a significant number of sex workers and queer and transgender people—some of whom were part of the minority who had criminal-justice involvement, having been formerly incarcerated because of their gender and sexual transgression. Part of what made Castro’s propaganda scheme so successful was that his regime’s repudiation of Marielitos found an eager audience in the United States among those who found it useful to fuel the nativist furnace. U.S. legislators, policymakers and many in the general public accepted Castro’s negative depiction of the Marielitos as truth. By 1983, the film Scarface had even fictionalized a Marielito as a druglord and violent criminal. Then and now, the boatlift proved incredibly unpopular among those living in the United States and is often cited as one of the most vivid examples of the dangers of lax immigration enforcement. In fact, many of President Jimmy Carter’s opponents listed Mariel as one of his and the Democratic Party’s greatest failures, even as his Republican successor, President Ronald Reagan, also embraced the Marielitos as part of an ideological campaign against Cuba. Julio Capó, Jr.

For an economist, there’s a straightforward way to study how low-skill immigration affects native workers: Find a large, sudden wave of low-skill immigrants arriving in one city only. Watch what happens to wages and employment for native workers in that city, and compare that to other cities where the immigrants didn’t go. An ideal “natural experiment” like this actually happened in Miami in 1980. Over just a few months, 125,000 mostly low-skill immigrants arrived from Mariel Bay, Cuba. This vast seaborne exodus — Fidel Castro briefly lifted Cuba’s ban on emigration -— is known as the Mariel boatlift. Over the next few months, the workforce of Miami rose by 8 percent. By comparison, normal immigration to the US increases the nationwide workforce by about 0.3 percent per year. So if immigrants compete with native workers, Miami in the 1980s is exactly where you should see natives’ wages drop. Berkeley’s Card examined the effects of the Cuban immigrants on the labor market in a massively influential study in 1990. In fact, that paper became one of the most cited in immigration economics. The design of the study was elegant and transparent. But even more than that, what made the study memorable was what Card found. In a word: nothing. The Card study found no difference in wage or employment trends between Miami — which had just been flooded with new low-skill workers — and other cities. This was true for workers even at the bottom of the skills ladder. Card concluded that “the Mariel immigration had essentially no effect on the wages or employment outcomes of non-Cuban workers in the Miami labor market. » (…) Economists ever since have tried to explain this remarkable result. Was it that the US workers who might have suffered a wage drop had simply moved away? Had low-skill Cubans made native Miamians more productive by specializing in different tasks, thus stimulating the local economy? Was it that the Cubans’ own demand for goods and services had generated as many jobs in Miami as they filled? Or perhaps was it that Miami employers shifted to production technologies that used more low-skill labor, absorbing the new labor supply? Regardless, there was no dip in wages to explain. The real-life economy was evidently more complex than an “Econ 101” model would predict. Such a model would require wages to fall when the supply of labor, through immigration, goes up. This is where two new studies came in, decades after Card’s — in 2015. One, by Borjas, claims that Card’s analysis had obscured a large fall in the wages of native workers by using too broad a definition of “low-skill worker.” Card’s study had looked at the wages of US workers whose education extended only to high school or less. That was a natural choice, since about half of the newly-arrived Cubans had a high school degree, and half didn’t. Borjas, instead, focuses on workers who did not finish high school — and claimed that the Boatlift caused the wages of those workers, those truly at the bottom of the ladder, to collapse. The other new study (ungated here), by economists Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov, of the UC Davis and UC Berkeley, reconfirms Card’s original result: It cannot detect an effect of the boatlift on Miami wages, even among workers who did not finish high school. (The wages of Miami workers with high school degrees (and no more than that) jump up right after the Mariel boatlift, relative to prior trends. The wages of those with less than a high school education appear to dip slightly, for a couple of years, although this is barely distinguishable amid the statistical noise. And these same inflation-adjusted wages were also falling in many other cities that didn’t receive a wave of immigrants, so it’s not possible to say with statistical confidence whether that brief dip on the right is real. It might have been — but economists can’t be sure. The rise on the left, in contrast, is certainly statistically significant, even relative to corresponding wage trends in other cities. Here is how the Borjas study reaches exactly the opposite conclusion. The Borjas study slices up the data much more finely than even Peri and Yasenov do. It’s not every worker with less than high school that he looks at. Borjas starts with the full sample of workers of high school or less — then removes women, and Hispanics, and workers who aren’t prime age (that is, he tosses out those who are 19 to 24, and 60 to 65). And then he removes workers who have a high school degree. In all, that means throwing out the data for 91 percent of low-skill workers in Miami in the years where Borjas finds the largest wage effect. It leaves a tiny sample, just 17 workers per year. When you do that, the average wages for the remaining workers look like this: (…) For these observations picked out of the broader dataset, average wages collapse by at least 40 percent after the boatlift. Wages fall way below their previous trend, as well as way below similar trends in other cities, and the fall is highly statistically significant. There are two ways to interpret these findings. The first way would be to conclude that the wage trend seen in the subgroup that Borjas focuses on — non-Hispanic prime-age men with less than a high school degree — is the “real” effect of the boatlift. The second way would be to conclude, as Peri and Yasenov do, that slicing up small data samples like this generates a great deal of statistical noise. If you do enough slicing along those lines, you can find groups for which wages rose after the Boatlift, and others for which it fell. In any dataset with a lot of noise, the results for very small groups will vary widely. Researchers can and do disagree about which conclusion to draw. But there are many reasons to favor the view that there is no compelling basis to revise Card’s original finding. There is not sufficient evidence to show that Cuban immigrants reduced any low-skill workers’ wages in Miami, even small minorities of them, and there isn’t much more that can be learned about the Mariel boatlift with the data we have. (…) Around 1980, the same time as the Boatlift, two things happened that would bring a lot more low-wage black men into the survey samples. First, there was a simultaneous arrival of large numbers of very low-income immigrants from Haiti without high school degrees: that is, non-Hispanic black men who earn much less than US black workers but cannot be distinguished from US black workers in the survey data. Nearly all hadn’t finished high school. That meant not just that Miami suddenly had far more black men with less than high school after 1980, but also that those black men had much lower earnings. Second, the Census Bureau, which ran the CPS surveys, improved its survey methods around 1980 to cover more low-skill black men due to political pressure after research revealed that many low-income black men simply weren’t being counted. (…) In sum, the evidence from the Mariel boatlift continues to support the conclusion of David Card’s seminal research: There is no clear evidence that wages fell (or that unemployment rose) among the least-skilled workers in Miami, even after a sudden refugee wave sharply raised the size of that workforce. This does not by any means imply that large waves of low-skill immigration could not displace any native workers, especially in the short term, in other times and places. But politicians’ pronouncements that immigrants necessarily do harm native workers must grapple with the evidence from real-world experiences to the contrary. Michael Clemens (Center for Global Development, Washington, DC)

His name was Luis Felipe. Born in Cuba in 1962, he came to the United States on a fishing boat and ended up in prison for shooting his girlfriend. He founded the New York chapter of the Latin Kings in 1986. Soon he was ordering murders from his prison cell. Esquire

Judge Martin says the extreme conditions are necessary to protect society. »I do not do it out of my sense of cruelty, » the judge said at the sentencing, after Mr. Felipe had expressed remorse for the killings. But noting that the defendant had been convicted for ordering the murder of three Latin Kings and the attempted murder of four others, the judge said that without such restrictions, »some of the young men sitting in this court today who are supporters of Mr. Felipe might well be murdered in the future. » (…) That Mr. Felipe, a man of charisma and intelligence, is nonetheless a ruthless criminal is not in dispute. His accounts of his background vary. He has said that his mother was a prostitute and that both parents are now dead. At the age of 9, he was sent to prison for robbery. On his 19th birthday in 1980, he arrived in the United States during the Mariel boatlift. In short order, Mr. Felipe became a street thug, settling in Chicago. There he joined the Latin Kings, a Hispanic organization established in the 1940’s. He moved to the Bronx. One night in 1981, in what has been described as a drunken accident, he shot and killed his girlfriend. He fled to Chicago and was not apprehended until 1984. Sentenced to nine years for second-degree manslaughter, he ended up at Collins Correctional Facility in Helmuth, N.Y. At Collins, he found an inmate system lorded over by black gangs and white guards. In 1986, he started a fledgling New York prison chapter of the Latin Kings. In a manifesto that followers circulated, he laid out elaborate laws and rituals, emphasizing Latin pride, family values, rigorous discipline and swift punishment. He was paroled in 1989 but by 1991 had returned to prison. He was eventually sent to Attica for a three-year sentence for possession of stolen property. His word spread, not least because he wrote thousands of letters, his prose a mix of flamboyant grandiosity and street bluntness. As King Blood, Inka, First Supreme Crown, Mr. Felipe corresponded with Latin Kings in and out of prison. (At its peak, the gang was estimated to have about 2,000 members.) He soared with self-aggrandizement, styling himself as both autocratic patriarch and jailhouse Ann Landers, dispensing advice about romance, family squabbles, schoolyard disputes. But in 1993 and 1994, disciplinary troubles erupted throughout the Latin Kings, with members vying for power, filching gang money, looking sideways at the wrong women. Infuriated, King Blood wrote to his street lieutenants: B.O.S. (beat on sight) and T.O.S. (terminate on sight). »Even while he was in Attica in segregation, he was able to order the leader of the Latin Kings on Rikers Island to murder someone who ended up being badly slashed in the face, » said Alexandra A. E. Shapiro, a Federal prosecutor. One victim was choked and beheaded. A second was killed accidentally during an attempt on another man. A third was gunned down. Federal authorities, who had been monitoring Mr. Felipe’s mail, arrested 35 Latin Kings. Thirty-four pleaded guilty. Only Mr. Felipe insisted on a trial. The Latin Kings still revere him, said Antonio Fernandez, King Tone, the gang’s new leader, who is trying to reposition it as a mainstream organization. »He brought a message of hope, » he said. NYT

Luis « King Blood » Felipe, who founded the New York chapter in 1986 (…) ran the gang from prison like a demented puppet-master. He ordered the murders of three Kings and plotted to murder three others. He routinely dispatched « T.O.S. » orders–shorthand for « Terminate on Sight. » In one particularly gory execution, a rival was strangled, decapitated and set afire in a bathtub. His Kings tattoo was peeled off his arm with a knife. Convicted of racketeering in 1996, Felipe was sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement to cut him off from the Kings. LA Times

Julio Gonzalez, a jilted lover whose arson revenge at the unlicensed Happy Land nightclub in the Bronx in 1990 claimed 87 lives, making him the nation’s worst single mass murderer at the time, died on Tuesday at a hospital in Plattsburgh, N.Y., where he had been taken from prison. He was 61 (…) Mr. Gonzalez was born in Holguín, a city in Oriente Province in Cuba, on Oct. 10, 1954. He served three years in prison in the 1970s for deserting the Cuban Army. In 1980, when he was 25, he joined what became known as the Mariel boatlift, an effort organized by Cuban-Americans and agreed to by the Cuban government that brought thousands of Cuban asylum-seekers to the United States. It was later learned that many of the refugees had been released from jails and mental hospitals. Mr. Gonzalez was said to have faked a criminal record as a drug dealer to help him gain passage. (…) Mr. Gonzalez had just lost his job at a Queens lamp warehouse when he showed up at Happy Land. There he argued heatedly with his girlfriend, Lydia Feliciano, about their six-year on-again, off-again relationship and about her quitting as a coat checker at the club. Around 3 a.m., a bouncer ejected him. According to testimony, Mr. Gonzalez walked three blocks to an Amoco service station, where he found an empty one-gallon container and bought $1 worth of gasoline from an attendant he knew there. He returned to the club. (…) Mr. Gonzalez splashed the gasoline at the bottom of a rickety staircase, the club’s only means of exit, and ignited it. Then he went home and fell asleep. (…) Ms. Feliciano was among the six survivors. She recounted her argument with Mr. Gonzalez to the police, who went to his apartment, where he confessed. “I got angry, the devil got to me, and I set the fire,” he told detectives. (…) During a video conference-call interview at the time, he said he had not realized how many people were inside Happy Land that night, that he had nothing against them and that his anger had been directed at the bouncer. NYT

Cet exode des Marielitos a commencé par un coup de force. Le 5 avril 1980, 10 000 Cubains entrent dans l’ambassade du Pérou à La Havane et demandent à ce pays de leur accorder asile. Dix jours plus tard, Castro déclare que ceux qui veulent quitter Cuba peuvent le faire à condition d’abandonner leurs biens et que les Cubains de Floride viennent les chercher au port de Mariel. L’hypothèse est que Castro voit dans cette affaire une double opportunité : Il se débarrasse d’opposants -il en profite également pour vider ses prisons et ses asiles mentaux et sans doute infiltrer, parmi les réfugiés, quelques agents castristes ; Il espère que cet afflux soudain d’exilés va profondément déstabiliser le sud de la Floride et affaiblir plus encore le brave Président Jimmy Carter, préchi-prêcheur démocrate des droits de l’homme, un peu trop à gauche pour endosser l’habit de grand Satan impérialiste que taille à tous les élus de la Maison Blanche le leader cubain. De fait, du 15 avril au 31 octobre 1980, quelque 125 000 Cubains quitteront l’île. 2 746 d’entre eux ont été considérés comme des criminels selon les lois des Etats-Unis et incarcérés. Le Nouvel Obs

Avec l’autorisation du président Fidel Castro, 125 000 Cubains quittent leur île par le port de Mariel pour trouver refuge aux États-Unis. Cet exode massif posera plusieurs problèmes aux Américains qui y mettront un terme après deux mois. Le 3 avril 1980, six Cubains entrent de force à l’ambassade du Pérou à La Havane pour s’y réfugier. Les autorités cubaines demandent leur retour sans succès. Voulant donner une leçon au Pérou, le président Castro fait retirer les gardes protégeant l’ambassade. Celle-ci est submergée par plus de 10 000 personnes qui sont vite aux prises avec des problèmes de salubrité et le manque de nourriture. Pendant que d’autres ambassades sont envahies (Costa Rica, Espagne), la communauté cubano-américaine entreprend une campagne de support. Voulant récupérer le mouvement, Castro annonce le 23 avril une politique de porte ouverte pour ceux qui veulent quitter Cuba. Il invite les Cubains habitant aux États-Unis à venir chercher leurs proches au port de Mariel. Cet exode, qui se fait avec 17 000 navires de toutes sortes, implique environ 125 000 personnes, en grande partie des gens de la classe ouvrière, des Noirs et des jeunes. Son envergure reflète un profond mécontentement face à l’économie cubaine et la baisse de la ferveur révolutionnaire. D’abord favorables à cet exode, les États-Unis sont vite débordés. Le 14 mai, le président Jimmy Carter fait établir un cordon de sécurité pour arrêter les navires. Placés dans des camps militaires et des prisons fédérales, les réfugiés sont interrogés à leur arrivée. Parmi eux, on retrouve des criminels et des malades mentaux qui ont quitté avec le soutien des autorités cubaines, ce qui a un effet négatif sur la population. Carter cherche à remplacer l’exode maritime par un pont aérien avec un quota de 3000 personnes par année. Mais aucun accord n’est conclu avec Cuba. Submergées par un exode en provenance de Haïti, les autorités américaines mettront fin à l’exode cubain le 20 juin 1980. Perspective monde

As BuzzFeed investigative reporter Ken Bensinger chronicles in his new book, Red Card: How the U.S. Blew the Whistle on the World’s Biggest Sports Scandal, the investigation’s origins began before FIFA handed the 2018 World Cup to Russia and the 2022 event to Qatar. The case had actually begun as an FBI probe into an illegal gambling ring the bureau believed was run by people with ties to Russian organized crime outfits. The ring operated out of Trump Tower in New York City. Eventually, the investigation spread to soccer, thanks in part to an Internal Revenue Service agent named Steve Berryman, a central figure in Bensinger’s book who pieced together the financial transactions that formed the backbone of the corruption allegations. But first, it was tips from British journalist Andrew Jennings and Christopher Steele ― the former British spy who is now known to American political observers as the man behind the infamous so-called “pee tape” dossier chronicling now-President Donald Trump’s ties to Russia ― that pointed the Americans’ attention toward the Russian World Cup, and the decades of bribery and corruption that had transformed FIFA from a modest organization with a shoestring budget into a multibillion-dollar enterprise in charge of the world’s most popular sport. Later, the feds arrested and flipped Chuck Blazer, a corrupt American soccer official and member of FIFA’s vaunted Executive Committee. It was Blazer who helped them crack the case wide open, as HuffPost’s Mary Papenfuss and co-author Teri Thompson chronicled in their book American Huckster, based on the 2014 story they broke of Blazer’s role in the scandal. Russia’s efforts to secure hosting rights to the 2018 World Cup never became a central part of the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice’s case. Thanks to Blazer, it instead focused primarily on CONCACAF, which governs soccer in the Caribbean and North and Central America, and other officials from South America. But as Bensinger explained in an interview with HuffPost this week, the FIFA case gave American law enforcement officials an early glimpse into the “Machiavellian Russia” of Vladimir Putin “that will do anything to get what it wants and doesn’t care how it does it.” And it was Steele’s role in the earliest aspects of the FIFA case, coincidentally, that fostered the relationship that led him to hand his Trump dossier to the FBI ― the dossier that has now helped form “a big piece of the investigative blueprint,” as Bensinger said, that former FBI director Robert Mueller is using in his probe of Russian meddling in the election that made Trump president. HuffPost

There are sort of these weird connections to everything going on in the political sphere in our country, which I think is interesting because when I was reporting the book out, it was mostly before the election. It was a time when Christopher Steele’s name didn’t mean anything. But what I figured out over time is that this had nothing to do with sour grapes, and the FBI agents who opened the case didn’t really care about losing the World Cup. The theory was that the U.S. investigation was started because the U.S. lost to Qatar, and Bill Clinton or Eric Holder or Barack Obama or somebody ordered up an investigation. What happened was that the investigation began in July or August 2010, four or five months before the vote happened. It starts because this FBI agent, who’s a long-term Genovese crime squad guy, gets a new squad ― the Eurasian Organized Crime Squad ― which is primarily focused on Russian stuff. It’s a squad that’s squeezed of resources and not doing much because under Robert Mueller, who was the FBI director at the time, the FBI was not interested in traditional crime-fighting. They were interested in what Mueller called transnational crime. So this agent looked for cases that he thought would score points with Mueller. And one of the cases they’re doing involves the Trump Tower. It’s this illegal poker game and sports book that’s partially run out of the Trump Tower. The main guy was a Russian mobster, and the FBI agent had gone to London ― that’s how he met Steele ― to learn about this guy. Steele told him what he knew, and they parted amicably, and the parting shot was, “Listen, if you have any other interesting leads in the future, let me know.” Steele had already been hired by the English bid for the 2018 World Cup at that point. What Chris Steele starts seeing on behalf of the English bid is the Russians doing, as it’s described in the book, sort of strange and questionable stuff. It looks funny, and it’s setting off alarm bells for Steele. So he calls the FBI agent back, and says, “You should look into what’s happening with the World Cup bid. » (…) It’s tempting to look at this as a reflection of the general U.S. writ large obsession with Russia, which certainly exists, but it’s also a different era. This was 2009, 2010. This was during the Russian reset. It was Obama’s first two years in office. He’s hugging Putin and talking about how they’re going to make things work. Russia is playing nice-nice. (…)That’s what I find interesting about this case is that, what we see in Russia’s attempt to win the World Cup by any means is the first sort of sign of the Russia we now understand exists, which is kind of a Machiavellian Russia that will do anything to get what it wants and doesn’t care how it does it. It was like a dress rehearsal for that. (…) It’s one of these things that looks like an accident, but so much of world history depends on these accidents. Chris Steele, when he was still at MI-6, investigated the death of Alexander Litvinenko, who was the Russian spy poisoned with polonium. It was Steele who ran that investigation and determined that Putin probably ordered it. And then Steele gets hired because of his expertise in Russia by the English bid, and he becomes the canary in the coal mine saying, “Uh oh, guys, it’s not going to be that easy, and things are looking pretty grim for you.” (…) I don’t know if that would have affected whether or not Chris Steele later gets hired by Fusion GPS to put together the Trump dossier. But it’s certain that the relationship he built because of the FIFA case meant that the FBI took it more seriously. (…) I think [FIFA vice president Jérôme Valcke] and others were recognizing this increasingly brazen attitude of the criminality within FIFA. They had gone from an organization where people were getting bribes and doing dirty stuff, but doing it very carefully behind closed doors. And it was transitioning to one where the impunity was so rampant that people thought they could do anything. And I think in his mind, awarding the World Cup to Russia under very suspicious circumstances and also awarding it to Qatar, which by any definition has no right to host this tournament, it felt to him and others like a step too far. I don’t think he had any advance knowledge that the U.S. was poking around on it, but he recognized that it was getting out of hand. People were handing out cash bribes in practically broad daylight, and as corrupt as these people were, they didn’t tend to do that. (…) The FIFA culture we know today didn’t start yesterday. It started in 1974 when this guy gets elected, and within a couple years, the corruption starts. And it starts with one bribe to Havelange, or one idea that he should be bribed. And it starts a whole culture, and the people all sort of learn from that same model. The dominoes fell over time. It’s not a new model, and things were getting more and more out of hand over time. FIFA had been able to successfully bat these challenges down over the years. There’s an attempted revolt in FIFA in 2001 or 2002 that Blatter completely shut down. The general secretary of FIFA was accusing Blatter and other people of either being involved in corruption or permitting corruption, and there’s a moment where it seems like the Executive Committee was going to turn against Blatter and vote him out and change everything. But they all blinked, and Blatter dispensed his own justice by getting rid of his No. 2 and putting in people who were going to be loyal to him. The effect of those things was more brazen behavior. (…) It was an open secret. I think it’s because soccer’s just too big and important in all these other countries. I think other countries have just never been able to figure out how to deal with it. The best you’d get was a few members of Parliament in England holding outraged press conferences or a few hearings, but nothing ever came of it. It’s just too much of a political hot potato because soccer elsewhere is so much more important than it is the U.S. People are terrified of offending the FIFA gods There’s a story about how Andrew Jennings, this British journalist, wanted to broadcast a documentary detailing FIFA corruption just a week or so before the 2010 vote, and when the British bid and the British government got a hold of it, they tried really hard to stifle the press. They begged the BBC not to air the documentary until after the vote, because they were terrified of FIFA. That’s reflective of the kind of attitudes that all these countries have. (…) it reminds me of questions about Chuck Blazer. Is he all bad, or all good? He’s a little bit of both. The U.S. women’s national team probably wouldn’t exist without him. The Women’s World Cup probably wouldn’t either. Major League Soccer got its first revenue-positive TV deal because of Chuck Blazer. (…) At the same time, he was a corrupt crook that stole a lot of money that could’ve gone to the game. And so, is he good or bad? Probably more bad than good, but he’s not all bad. That applies to the Gold Cup. The Gold Cup is a totally artificial thing that was made up ultimately as a money-making scheme for Blazer, but in the end, it’s probably benefited soccer in this country. So it’s clearly not all bad. (…) The money stolen from the sport isn’t just the bribes. Let’s say I’m a sports marketing firm, and I bribe you a million dollars to sign over a rights contract to me. The first piece of it is that million dollars that could have gone to the sport. But it’s also the opportunity cost: What would the value of those rights have been if it was taken to the free market instead of a bribe? All that money is taken away from the sport. And the second thing was traveling to South America and seeing the conditions of soccer for fans, for kids and for women. That was really eye-opening. There are stadiums in Argentina and Brazil that are absolutely decrepit. And people would explain, the money that was supposed to come to these clubs never comes. You have kids still playing with the proverbial ball made of rags and duct tape, and little girls who can’t play because there are no facilities or leagues for women at all. When you see that, and then you see dudes making millions in bribes and also marketing guys making far more from paying the bribes, I started to get indignant about it. FIFA always ties itself to children and the good of the game. But it’s absurd when you see how they operate. The money doesn’t go to kids. It goes to making soccer officials rich. (…) When massive amounts of money mixes with a massively popular cultural phenomenon, is it ever going to be clean? I wish it would be different, but it seems kind of hopeless. How do you regulate soccer, and who can oversee this to make sure that people behave in an ethical, clean and fair way that benefits everyone else? It’s not an accident that every single international sports organization is based in Switzerland. The answer is because the Swiss, not only do they offer them a huge tax break, they also basically say, “You can do whatever you want and we’re not going to bother you.” That’s exactly what these groups want. Well, how do you regulate that? I don’t think the U.S. went in saying, “We’re going to regulate soccer.” I think they thought if we can give soccer a huge kick in the ass, if we can create so much public and political pressure on them that sponsors will run away, they’ll feel they have no option but to react and clean up their act. It’s sort of, kick ’em where it hurts. (…) But also, the annoying but true reality of FIFA is that when the World Cup is happening, all the soccer fans around the world forget all their anger and just want to watch the tournament. For three and a half years, everyone bitches about what a mess FIFA is, and then during the World Cup everyone just wants to watch soccer. There could be some reinvigoration in the next few months when the next stupid scandal appears. And I do think Qatar could reinvigorate more of that. There’s a tiny piece of me that thinks we could still see Qatar stripped of the World Cup. That would certainly spur a lot of conversation about this. Ken Bensinger

The United States has the world’s largest trade deficit. It’s been that way since 1975. The deficit in goods and services was $566 billion in 2017. Imports were $2.895 trillion and exports were only $2.329 trillion. The U.S. trade deficit in goods, without services, was $810 billion. The United States exported $1.551 trillion in goods. The biggest categories were commercial aircraft, automobiles, and food. It imported $2.361 trillion. The largest categories were automobiles, petroleum, and cell phones. (…) The Largest U.S. Deficit Is With China More than 65 percent of the U.S. trade deficit in goods was with China. The $375 billion deficit with China was created by $506 billion in imports. The main U.S. imports from China are consumer electronics, clothing, and machinery. Many of these imports are actually made by American companies. They ship raw materials to be assembled in China for a lower cost. They are counted as imports even though they create income and profit for these U.S. companies. Nevertheless, this practice does outsource manufacturing jobs. America only exported $130 billion in goods to China. The top three exports were agricultural products, aircraft, and electrical machinery. The second largest trade deficit is $69 billion with Japan. The world’s fifth largest economy needs the agricultural products, industrial supplies, aircraft, and pharmaceutical products that the United States makes. Exports totaled $68 billion in 2017.Imports were higher, at $137 billion. Much of this was automobiles, with industrial supplies and equipment making up another large portion. Trade has improved since the 2011 earthquake, which slowed the economy and made auto parts difficult to manufacture for several months. The U.S. trade deficit with Germany is $65 billion. The United States exports $53 billion, a large portion of which is automobiles, aircraft, and pharmaceuticals. It imports $118 billion in similar goods: automotive vehicles and parts, industrial machinery, and medicine. (…) The trade deficit with Canada is $18 billion. That’s only 3 percent of the total Canadian trade of $582 billion. The United States exports $282 billion to Canada, more than it does to any other country. It imports $300 billion. The largest export by far is automobiles and parts. Other large categories include petroleum products and industrial machinery and equipment. The largest import is crude oil and gas from Canada’s abundant shale oil fields. The trade deficit with Mexico is $71 billion. Exports are $243 billion, mostly auto parts and petroleum products. Imports are $314 billion, with cars, trucks, and auto parts being the largest components. The Balance

On connaît les photos de ces hommes et de ces femmes débarquant sur des plages européennes, engoncés dans leurs gilets de sauvetage orange, tentant à tout prix de maintenir la tête de leur enfant hors de l’eau. Impossible également d’oublier l’image du corps du petit Aylan Kurdi, devenu en 2016 le symbole planétaire du drame des migrants. Ce que l’on sait moins c’est que le « business » des passeurs rapporte beaucoup d’argent. Selon la première étude du genre de l’Office des Nations unies contre la drogue et le crime (l’UNODC), le trafic de migrants a rapporté entre 5,5 et 7 milliards de dollars (entre 4,7 et 6 milliards d’euros) en 2016. C’est l’équivalent de ce que l’Union européenne a dépensé la même année dans l’aide humanitaire, selon le rapport. (…) En 2016, au moins 2,5 millions de migrants sont passés entre les mains de passeurs, estime l’UNODC qui rappelle la difficulté d’évaluer une activité criminelle. De quoi faire fructifier les affaires de ces contrebandiers. Cette somme vient directement des poches des migrants qui paient des criminels pour voyager illégalement. Le tarif varie en fonction de la distance à parcourir, du nombre de frontières, les moyens de transport utilisés, la production de faux papiers… La richesse supposée du client est un facteur qui fait varier les prix. Evidemment, payer plus cher ne rend pas le voyage plus sûr ou plus confortable, souligne l’UNODC. Selon les estimations de cette agence des Nations unies, ce sont les passages vers l’Amérique du Nord qui rapportent le plus. En 2016, jusqu’à 820 000 personnes ont traversé la frontière illégalement, versant entre 3,1 et 3,6 milliards d’euros aux trafiquants. Suivent les trois routes de la Méditerranée vers l’Union européenne. Environ 375 000 personnes ont ainsi entrepris ce voyage en 2016, rapportant entre 274 et 300 millions d’euros aux passeurs. Pour atteindre l’Europe de l’Ouest, un Afghan peut ainsi dépenser entre 8000 € et 12 000 €. Sans surprise, les rédacteurs du rapport repèrent que l’Europe est une des destinations principales des migrants. (…) Les migrants qui arrivent en Italie sont originaires à 89 % d’Afrique, de l’Ouest principalement. 94 % de ceux qui atteignent l’Espagne sont également originaires d’Afrique, de l’Ouest et du Nord. En revanche, la Grèce accueille à 85 % des Afghans, Syriens et des personnes originaires des pays du Moyen-Orient. (…) des milliers de citoyens de pays d’Amérique centrale et de Mexicains traversent chaque année la frontière qui sépare les Etats-Unis du Mexique. Les autorités peinent cependant à quantifier les flux. Ce que l’on sait c’est qu’en 2016, 2 404 personnes ont été condamnées pour avoir fait passer des migrants aux Etats-Unis. 65 d’entre eux ont été condamnés pour avoir fait passer au moins 100 personnes.Toujours en 2016, le Mexique, qui fait office de « pays-étape » pour les voyageurs, a noté que les Guatémaltèques, les Honduriens et les Salvadoriens formaient les plus grosses communautés sur son territoire. En 2016, les migrants caribéens arrivaient principalement d’Haïti, note encore l’UNODC. (…) Sur les 8189 décès de migrants recensés par l’OIM en 2016, 3832 sont morts noyés (46 %) en traversant la Méditerranée. Les passages méditerranéens sont les plus mortels. L’un d’entre eux force notamment les migrants à parcourir 300 kilomètres en haute mer sur des embarcations précaires. C’est aussi la cruauté des passeurs qui est en cause. L’UNODC décrit le sort de certaines personnes poussées à l’eau par les trafiquants qui espèrent ainsi échapper aux gardes-côtes. Le cas de centaines de personnes enfermées dans des remorques sans ventilation, ni eau ou nourriture pendant des jours est également relevé. Meurtre, extorsion, torture, demande de rançon, traite d’être humain, violences sexuelles sont également le lot des migrants, d’où qu’ils viennent. En 2017, 382 migrants sont décédés de la main des hommes, soit 6 % des décès. (…) Le passeur est le plus souvent un homme mais des femmes (des compagnes, des sœurs, des filles ou des mères) sont parfois impliquées dans le trafic, définissent les rédacteurs de l’étude. Certains parviennent à gagner modestement leur vie, d’autres, membres d’organisations et de mafias font d’importants profits. Tous n’exercent pas cette activité criminelle à plein temps. Souvent le passeur est de la même origine que ses victimes. Il parle la même langue et partage avec elles les mêmes repères culturels, ce qui lui permet de gagner leur confiance. Le recrutement des futurs « clients » s’opère souvent dans les camps de réfugiés ou dans les quartiers pauvres. Facebook, Viber, Skype ou WhatsApp sont devenus des indispensables du contrebandier qui veut faire passer des migrants. Arrivé à destination, le voyageur publie un compte rendu sur son passeur. Il décrit s’il a triché, échoué ou s’il traitait mal les migrants. Un peu comme une note de consommateur, rapporte l’UNODC. Mieux encore, les réseaux sociaux sont utilisés par les passeurs pour leur publicité. Sur Facebook, les trafiquants présentent leurs offres, agrémentent leur publication d’une photo, détaillent les prix et les modalités de paiement. L’agence note que, sur Facebook, des passeurs se font passer pour des ONG ou des agences de voyages européennes qui organisent des passages en toute sécurité. D’autres, qui visent particulièrement les Afghans, se posent en juristes spécialistes des demandes d’asile… Le Parisien

Mr. Trump’s anger at America’s allies embodies, however unpleasantly, a not unreasonable point of view, and one that the rest of the world ignores at its peril: The global world order is unbalanced and inequitable. And unless something is done to correct it soon, it will collapse, with or without the president’s tweets. While the West happily built the liberal order over the past 70 years, with Europe at its center, the Americans had the continent’s back. In turn, as it unravels, America feels this loss of balance the hardest — it has always spent the most money and manpower to keep the system working. The Europeans have basically been free riders on the voyage, spending almost nothing on defense, and instead building vast social welfare systems at home and robust, well-protected export industries abroad. Rather than lash back at Mr. Trump, they would do better to ask how we got to this place, and how to get out. The European Union, as an institution, is one of the prime drivers of this inequity. At the Group of 7, for example, the constituent countries are described as all equals. But in reality, the union puts a thumb on the scales in its members’ favor: It is a highly integrated, well-protected free-trade area that gives a huge leg up to, say, German car manufacturers while essentially punishing American companies who want to trade in the region. The eurozone offers a similar unfair advantage. If it were not for the euro, Germany would long ago have had to appreciate its currency in line with its enormous export surplus. (…) how can the very same politicians and journalists who defended the euro bailout payments during the financial crisis, arguing that Germany profited disproportionately from the common currency, now go berserk when Mr. Trump makes exactly this point? German manufacturers also have the advantage of operating in a common market with huge wage gaps. Bulgaria, one of the poorest member states, has a per capita gross domestic product roughly equal to that of Gabon, while even in Slovakia, Poland and Hungary — three relative success stories among the recent entrants to the union — that same measure is still roughly a third of what it is in Germany. Under the European Union, German manufacturers can assemble their cars in low-wage countries and export them without worrying about tariffs or other trade barriers. If your plant sits in Detroit, you might find the president’s anger over this fact persuasive. Mr. Trump is not the first president to complain about the unfair burden sharing within NATO. He’s merely the first president not just to talk tough, but to get tough. (…) All those German politicians who oppose raising military spending from a meager 1.3 percent of gross domestic product should try to explain to American students why their European peers enjoy free universities and health care, while they leave it up to others to cover for the West’s military infrastructure (…) When the door was opened, in 2001, many in the West believed that a growing Chinese middle class, enriched by and engaged with the world economy, would eventually claim voice and suffrage, thereby democratizing China. The opposite has happened. China, which has grown wealthy in part by stealing intellectual property from the West, is turning into an online-era dictatorship, while still denying reciprocity in investment and trade relations. (…) China’s unchecked abuse of the global free-trade regime makes a mockery of the very idea that the world can operate according to a rules-based order. Again, while many in the West have talked the talk about taking on China, only Mr. Trump has actually done something about it. Jochen Bittner (Die Zeit)

Is the Trump administration out to wreck the liberal world order? No, insisted Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in an interview at his office in Foggy Bottom last week: The administration’s aim is to align that world order with 21st-century realities. Many of the economic and diplomatic structures Mr. Trump stands accused of undermining, Mr. Pompeo argues, were developed in the aftermath of World War II. Back then, he tells me, they “made sense for America.” But in the post-Cold War era, amid a resurgence of geopolitical competition, “I think President Trump has properly identified a need for a reset.” Mr. Trump is suspicious of global institutions and alliances, many of which he believes are no longer paying dividends for the U.S. “When I watch President Trump give guidance to our team,” Mr. Pompeo says, “his question is always, ‘How does that structure impact America?’ ” The president isn’t interested in how a given rule “may have impacted America in the ’60s or the ’80s, or even the early 2000s,” but rather how it will enhance American power “in 2018 and beyond.” Mr. Trump’s critics have charged that his “America First” strategy reflects a retreat from global leadership. “I see it fundamentally differently,” Mr. Pompeo says. He believes Mr. Trump “recognizes the importance of American leadership” but also of “American sovereignty.” That means Mr. Trump is “prepared to be disruptive” when the U.S. finds itself constrained by “arrangements that put America, and American workers, at a disadvantage.” Mr. Pompeo sees his task as trying to reform rules “that no longer are fair and equitable” while maintaining “the important historical relationships with Europe and the countries in Asia that are truly our partners.” The U.S. relationship with Germany has come under particular strain. Mr. Pompeo cites two reasons. “It is important that they demonstrate a commitment to securing their own people,” he says, in reference to Germany’s low defense spending. “When they do so, we’re prepared to do the right thing and support them.” And then there’s trade. The Germans, he says, need to “create tariff systems and nontariff-barrier systems that are equitable, reciprocal.” But Mr. Pompeo does not see the U.S.-German rift as a permanent reorientation of U.S. foreign policy. Once the defense and trade issues are addressed, “I’m very confident that the relationship will go from these irritants we see today to being as strong as it ever was.” (…) In addition to renegotiating relationships with existing allies, the Trump administration is facing newly assertive great-power adversaries. “For a decade plus,” Mr. Pompeo says, U.S. foreign policy was “very focused on counterrorism and much less on big power struggles.” Today, while counterterrorism remains a priority, geopolitics is increasingly defined by conflicts with powerful states like China and Russia. Mr. Pompeo says the U.S. must be assertive but flexible in dealing with both Beijing and Moscow. He wants the U.S. relationship with China to be defined by rule-writing and rule-enforcing, not anarchic struggle. China, he says, hasn’t honored “the normal set of trade understandings . . . where these nation states would trade with each other on fair and reciprocal terms; they just simply haven’t done it. They’ve engaged in intellectual property theft, predatory economic practices.” Avoiding a more serious confrontation with China down the line will require both countries to appreciate one another’s long-term interests. The U.S. can’t simply focus on “a tariff issue today, or a particular island China has decided to militarize” tomorrow. Rather, the objective must be to create a rules-based structure to avoid a situation in which “zero-sum is the endgame for the two countries.” Mr. Pompeo also sees room for limited cooperation with Russia even as the U.S. confronts its revisionism. “There are many things about which we disagree. Our value sets are incredibly different, but there are also pockets where we find overlap,” he says. “That’s the challenge for a secretary of state—to identify those places where you can work together, while protecting America against the worst pieces of those governments’ activities.” (…) And the president’s agenda, as Mr. Pompeo communicates it, is one of extraordinary ambition: to rewrite the rules of world order in America’s favor while working out stable relationships with geopolitical rivals. Those goals may prove elusive. Inertia is a powerful force in international relations, and institutions and pre-existing agreements are often hard to reform. Among other obstacles, the Trump agenda creates the risk of a global coalition forming against American demands. American efforts to negotiate more favorable trading arrangements could lead China, Europe and Japan to work jointly against the U.S. That danger is exacerbated by Mr. Trump’s penchant for dramatic gestures and his volatile personal style. Yet the U.S. remains, by far, the world’s most powerful nation, and many countries will be looking for ways to accommodate the administration at least partially. Mr. Trump is right that the international rules and institutions developed during the Cold War era must be retooled to withstand new political, economic and military pressures. Mr. Pompeo believes that Mr. Trump’s instincts, preferences, and beliefs constitute a coherent worldview. (…) The world will soon see whether the president’s tweets of iron can be smoothly sheathed in a diplomatic glove. Walter Russell Mead

Illegal and illiberal immigration exists and will continue to expand because too many special interests are invested in it. It is one of those rare anomalies — the farm bill is another — that crosses political party lines and instead unites disparate elites through their diverse but shared self-interests: live-and-let-live profits for some and raw political power for others. For corporate employers, millions of poor foreign nationals ensure cheap labor, with the state picking up the eventual social costs. For Democratic politicos, illegal immigration translates into continued expansion of favorable political demography in the American Southwest. For ethnic activists, huge annual influxes of unassimilated minorities subvert the odious melting pot and mean continuance of their own self-appointed guardianship of salad-bowl multiculturalism. Meanwhile, the upper middle classes in coastal cocoons enjoy the aristocratic privileges of having plenty of cheap household help, while having enough wealth not to worry about the social costs of illegal immigration in terms of higher taxes or the problems in public education, law enforcement, and entitlements. No wonder our elites wink and nod at the supposed realities in the current immigration bill, while selling fantasies to the majority of skeptical Americans. Victor Davis Hanson

Much has been written — some of it either inaccurate or designed to obfuscate the issue ahead of the midterms for political purposes — about the border fiasco and the unfortunate separation of children from parents. (…) The media outrage usually does not include examination of why the Trump administration is enforcing existing laws that it inherited from the Bush and Obama administrations that at any time could have been changed by both Democratic and Republican majorities in Congress; of the use of often dubious asylum claims as a way of obtaining entry otherwise denied to those without legal authorization — a gambit that injures or at least hampers thousands with legitimate claims of political persecution; of the seeming unconcern for the safety of children by some would-be asylum seekers who illegally cross the border, rather than first applying legally at a U.S. consulate abroad; of the fact that many children are deliberately sent ahead, unescorted on such dangerous treks to help facilitate their own parents’ later entrance; of the cynicism of the cartels that urge and facilitate such mass rushes to the border to overwhelm general enforcement; and of the selective outrage of the media in 2018 in a fashion not known under similar policies and detentions of the past. In 2014, during a similar rush, both Barack Obama (“Do not send your children to the borders. If they do make it, they’ll get sent back.”) and Hillary Clinton (“We have to send a clear message, just because your child gets across the border, that doesn’t mean the child gets to stay. So, we don’t want to send a message that is contrary to our laws or will encourage more children to make that dangerous journey.”) warned — again to current media silence — would-be asylum seekers not to use children as levers to enter the U.S. (…) Mexico is the recipient of about $30 billion in annual remittances (aside from perhaps more than $20 billion annually sent to Central America) from mostly illegal aliens within the U.S. It is the beneficiary of an annual $71 billion trade surplus with the U.S. And it is mostly culpable for once again using illegal immigration and the lives of its own citizens — and allowing Central Americans unfettered transit through its country — as cynical tools of domestic and foreign policy. Illegal immigration, increasingly of mostly indigenous peoples, ensures an often racist Mexico City a steady stream of remittances (now its greatest source of foreign exchange), without much worry about how its indigent abroad can scrimp to send such massive sums back to Mexico. Facilitating illegal immigration also establishes and fosters a favorable expatriate demographic inside the U.S. that helps to recalibrate U.S. policy favorably toward Mexico. And Mexico City also uses immigration as a policy irritant to the U.S. that can be magnified or lessened, depending on Mexico’s own particular foreign-policy goals and moods at any given time.

All of the above call into question whether Mexico is a NAFTA ally, a neutral, or a belligerent, a status that may become perhaps clearer during its upcoming presidential elections. So far, it assumes that the optics of this human tragedy facilitate its own political agendas, but it may be just as likely that its cynicism could fuel renewed calls for a wall and reexamination of the entire Mexican–U.S. relationship and, indeed, NAFTA. Victor Davis Hanson

This year there have been none of the usual Iranian provocations — frequent during the Obama administration — of harassing American ships in the Persian Gulf. Apparently, the Iranians now realize that anything they do to an American ship will be replied to with overwhelming force. Ditto North Korea. After lots of threats from Kim Jong-un about using his new ballistic missiles against the United States, Trump warned that he would use America’s far greater arsenal to eliminate North Korea’s arsenal for good. Trump is said to be undermining NATO by questioning its usefulness some 69 years after its founding. Yet this is not 1948, and Germany is no longer down. The United States is always in. And Russia is hardly out but is instead cutting energy deals with the Europeans. More significantly, most NATO countries have failed to keep their promises to spend 2 percent of their GDP on defense. Yet the vast majority of the 29 alliance members are far closer than the U.S. to the dangers of Middle East terrorism and supposed Russian bullying. Why does Germany by design run up a $65 billion annual trade surplus with the United States? Why does such a wealthy country spend only 1.2 percent of its GDP on defense? And if Germany has entered into energy agreements with a supposedly dangerous Vladimir Putin, why does it still need to have its security subsidized by the American military? Trump approaches NAFTA in the same reductionist way. The 24-year-old treaty was supposed to stabilize, if not equalize, all trade, immigration, and commerce between the three supposed North American allies. It never quite happened that way. Unequal tariffs remained. Both Canada and Mexico have substantial trade surpluses with the U.S. In Mexico’s case, it enjoys a $71 billion surplus, the largest of U.S. trading partners with the exception of China. Canada never honored its NATO security commitment. It spends only 1 percent of its GDP on defense, rightly assuming that the U.S. will continue to underwrite its security. During the lifetime of NAFTA, Mexico has encouraged millions of its citizens to enter the U.S. illegally. Mexico’s selfish immigration policy is designed to avoid internal reform, to earn some $30 billion in annual expatriate remittances, and to influence U.S. politics. Yet after more than two decades of NAFTA, Mexico is more unstable than ever. Cartels run entire states. Murders are at a record high. Entire towns in southern Mexico have been denuded of their young males, who crossed the U.S. border illegally. The U.S. runs a huge trade deficit with China. The red ink is predicated on Chinese dumping, patent and copyright infringement, and outright cheating. Beijing illegally occupies neutral islands in the South China Sea, militarizes them, and bullies its neighbors. All of the above has become the “normal” globalized world. But in 2016, red-state America rebelled at the asymmetry. The other half of the country demonized the red-staters as protectionists, nativists, isolationists, populists, and nationalists. However, if China, Europe, and other U.S. trading partners had simply followed global trading rules, there would have been no Trump pushback — and probably no Trump presidency at all. Had NATO members and NAFTA partners just kept their commitments, and had Mexico not encouraged millions of its citizens to crash the U.S. border, there would now be little tension between allies. Instead, what had become abnormal was branded the new normal of the post-war world. Again, a rich and powerful U.S. was supposed to subsidize world trade, take in more immigrants than all the nations of the world combined, protect the West, and ensure safe global communications, travel, and commerce. After 70 years, the effort had hollowed out the interior of America, creating two separate nations of coastal winners and heartland losers. Trump’s entire foreign policy can be summed up as a demand for symmetry from all partners and allies, and tit-for-tat replies to would-be enemies. Did Trump have to be so loud and often crude in his effort to bully America back to reciprocity? Who knows? But it seems impossible to imagine that globalist John McCain, internationalist Barack Obama, or gentlemanly Mitt Romney would ever have called Europe, NATO, Mexico, and Canada to account, or warned Iran or North Korea that tit would be met by tat. Victor Davis Hanson

Attention: un dépotoir peut en cacher un autre !

Au lendemain du Sommet de l’Otan et de la visite au Royaume-Uni …

D’un président américain contre lequel se sont à nouveau déchainés nos médias et nos belles âmes …

Et en cette finale de la Coupe du monde en un pays qui, entre dopage et corruption, empoisonne les citoyens de ses partenaires …

A l’heure où des mensonges nucléaires et de l’aventurisme militaire des Iraniens …

Aux méga-excédents commerciaux et filouteries sur la propriété intellectuelle des Chinois …

Comme aux super surplus du commerce extérieur, la radinerie défensive et la mise sous tutelle énergétique russe des Allemands …

Et sans parler, entre deux attentats terroristes ou émeutes urbaines, du « business » juteux (quelque 7 milliards annuels quand même !) des passeurs de prétendus « réfugiés » …

Sur fond de trahison continue de nos clercs sur l’immigration incontrôlée …

L’actualité comme les sondages confirment désormais presque quotidiennement les fortes intuitions de l’éléphant dans le magasin de porcelaine …

Comment qualifier un pays qui …

Derrière les « fake news » et images victimaires dont nous bassinent jour après jour nos médias …

Et entre le contrôle d’états entiers par les cartels de la drogue, les taux d’homicides records et les villes entières vidées de leurs forces vives par l’émigration sauvage …

Se permet non seulement, comme le rappelle l’historien militaire américain Victor Davis Hanson, d’intervenir dans la politique américaine …

Mais encourage, à la Castro et repris de justice compris, ses citoyens par millions à pénétrer illégalement aux États-Unis …

Alors qu’il bénéficie par ailleurs, avec plus de 70 milliards de dollars et sans compter les quelque 30 milliards de ses expatriés, du plus important excédent commercial avec les Etats-Unis après la Chine ?

Reciprocity Is the Method to Trump’s Madness

Victor Davis Hanson

National Review

July 12, 2018

The president sends a signal: Treat us the way we treat you, and keep your commitments.Critics of Donald Trump claim that there’s no rhyme or reason to his foreign policy. But if there is a consistency, it might be called reciprocity.

Trump tries to force other countries to treat the U.S. as the U.S. treats them. In “don’t tread on me” style, he also warns enemies that any aggressive act will be replied to in kind.

The underlying principle of Trump commercial reciprocity is that the United States is no longer powerful or wealthy enough to alone underwrite the security of the West. It can no longer assume sole enforcement of the rules and protocols of the post-war global order.

This year there have been none of the usual Iranian provocations — frequent during the Obama administration — of harassing American ships in the Persian Gulf. Apparently, the Iranians now realize that anything they do to an American ship will be replied to with overwhelming force.

Ditto North Korea. After lots of threats from Kim Jong-un about using his new ballistic missiles against the United States, Trump warned that he would use America’s far greater arsenal to eliminate North Korea’s arsenal for good.

Trump is said to be undermining NATO by questioning its usefulness some 69 years after its founding. Yet this is not 1948, and Germany is no longer down. The United States is always in. And Russia is hardly out but is instead cutting energy deals with the Europeans.

More significantly, most NATO countries have failed to keep their promises to spend 2 percent of their GDP on defense.

Yet the vast majority of the 29 alliance members are far closer than the U.S. to the dangers of Middle East terrorism and supposed Russian bullying.

Why does Germany by design run up a $65 billion annual trade surplus with the United States? Why does such a wealthy country spend only 1.2 percent of its GDP on defense? And if Germany has entered into energy agreements with a supposedly dangerous Vladimir Putin, why does it still need to have its security subsidized by the American military?

Canada never honored its NATO security commitment. It spends only 1 percent of its GDP on defense, rightly assuming that the U.S. will continue to underwrite its security.

Trump approaches NAFTA in the same reductionist way. The 24-year-old treaty was supposed to stabilize, if not equalize, all trade, immigration, and commerce between the three supposed North American allies.

It never quite happened that way. Unequal tariffs remained. Both Canada and Mexico have substantial trade surpluses with the U.S. In Mexico’s case, it enjoys a $71 billion surplus, the largest of U.S. trading partners with the exception of China.

Canada never honored its NATO security commitment. It spends only 1 percent of its GDP on defense, rightly assuming that the U.S. will continue to underwrite its security.

During the lifetime of NAFTA, Mexico has encouraged millions of its citizens to enter the U.S. illegally. Mexico’s selfish immigration policy is designed to avoid internal reform, to earn some $30 billion in annual expatriate remittances, and to influence U.S. politics.

Yet after more than two decades of NAFTA, Mexico is more unstable than ever. Cartels run entire states. Murders are at a record high. Entire towns in southern Mexico have been denuded of their young males, who crossed the U.S. border illegally.

The U.S. runs a huge trade deficit with China. The red ink is predicated on Chinese dumping, patent and copyright infringement, and outright cheating. Beijing illegally occupies neutral islands in the South China Sea, militarizes them, and bullies its neighbors.

All of the above has become the “normal” globalized world.

If China, Europe, and other U.S. trading partners had simply followed global trading rules, there would have been no Trump pushback — and probably no Trump presidency at all.

But in 2016, red-state America rebelled at the asymmetry. The other half of the country demonized the red-staters as protectionists, nativists, isolationists, populists, and nationalists.

However, if China, Europe, and other U.S. trading partners had simply followed global trading rules, there would have been no Trump pushback — and probably no Trump presidency at all.

Had NATO members and NAFTA partners just kept their commitments, and had Mexico not encouraged millions of its citizens to crash the U.S. border, there would now be little tension between allies.

Instead, what had become abnormal was branded the new normal of the post-war world.

Again, a rich and powerful U.S. was supposed to subsidize world trade, take in more immigrants than all the nations of the world combined, protect the West, and ensure safe global communications, travel, and commerce.

After 70 years, the effort had hollowed out the interior of America, creating two separate nations of coastal winners and heartland losers.

Trump’s entire foreign policy can be summed up as a demand for symmetry from all partners and allies, and tit-for-tat replies to would-be enemies.

Did Trump have to be so loud and often crude in his effort to bully America back to reciprocity?

Who knows?

But it seems impossible to imagine that globalist John McCain, internationalist Barack Obama, or gentlemanly Mitt Romney would ever have called Europe, NATO, Mexico, and Canada to account, or warned Iran or North Korea that tit would be met by tat.

Voir aussi:

Pompeo on What Trump Wants

An interview with Trump’s top diplomat on America First and ‘the need for a reset.’

Walter Russell Mead

The Wall Street Journal

June 25, 2018

De Cuba aux Etats-Unis : il y a trente ans, les Marielitos

C’était il y a trente ans très exactement. Mai 1980. J’étais jeune journaliste, envoyé spécial de Libération à Key West, en Floride. Je restais des heures, fasciné, sur le quai du port où arrivaient, les unes après les autres en un flot continu extraordinaire, des embarcations diverses -bateaux de pêche, petits et gros, vedettes de promenade, yachts chics– chargées de réfugiés cubains.

C’était une noria incessante, menée avec beaucoup d’enthousiasme. Ces bateaux battaient tous pavillon des Etats-Unis et, pour la plupart, étaient la propriété d’exilés cubains vivant en Floride. Ils débarquaient leurs passagers sous les vives lumières des télévisions et les applaudissements d’une foule de badauds émus aux larmes et scrutant chaque visage avec intensité, dans l’espoir d’y retrouver les traits d’un parent, d’un ami ou d’un amour perdu de vue depuis plus de vingt ans.

Puis les bateaux repartaient pour un nouveau voyage à Mariel, le port cubain d’où partaient les exilés et qui leur donnera un surnom, « los Marielitos ».

La Croix Rouge et la logistique gouvernementale américaine ont fait du bon travail. Les arrivants, épuisés, l’air perdu, souvent inquiets, étaient accueillis avec égards, hydratés, nourris et enveloppés de couvertures.

Ils passaient à travers un double contrôle, médical et personnel, avant d’être rassemblés sous un immense hangar, libres de répondre, s’ils le souhaitaient, aux questions des journalistes, avant d’être transportés par avion à Miami.

Quand les Cubains étaient accueillis sous les bravos

Ceux que j’ai rencontrés, dans ces instants encore très incertains pour eux, racontaient plus ou moins la même histoire : la misère de tous les jours sous la surveillance constante des CDR, les Comités de la révolution, les commissaires politiques du quartier qui avaient (et ont toujours) le pouvoir de vous rendre la vie à peu près tolérable ou de vous la pourrir à jamais.

Oser dire qu’on aurait aimé vivre ailleurs n’arrangeait pas votre cas. Un mot du CDR et vous perdiez votre boulot. Le travail privé n’existant pas, le seul fait de survivre était l’indice d’un délit, genre travail au noir. Pour des raisons éminemment politiques, vous vous retrouviez donc en prison, délinquant de droit commun.

Bref, la routine infernale, les engrenages implacables et cruels de la criminalisation de la vie quotidienne pour quiconque ne courbait pas l’échine.

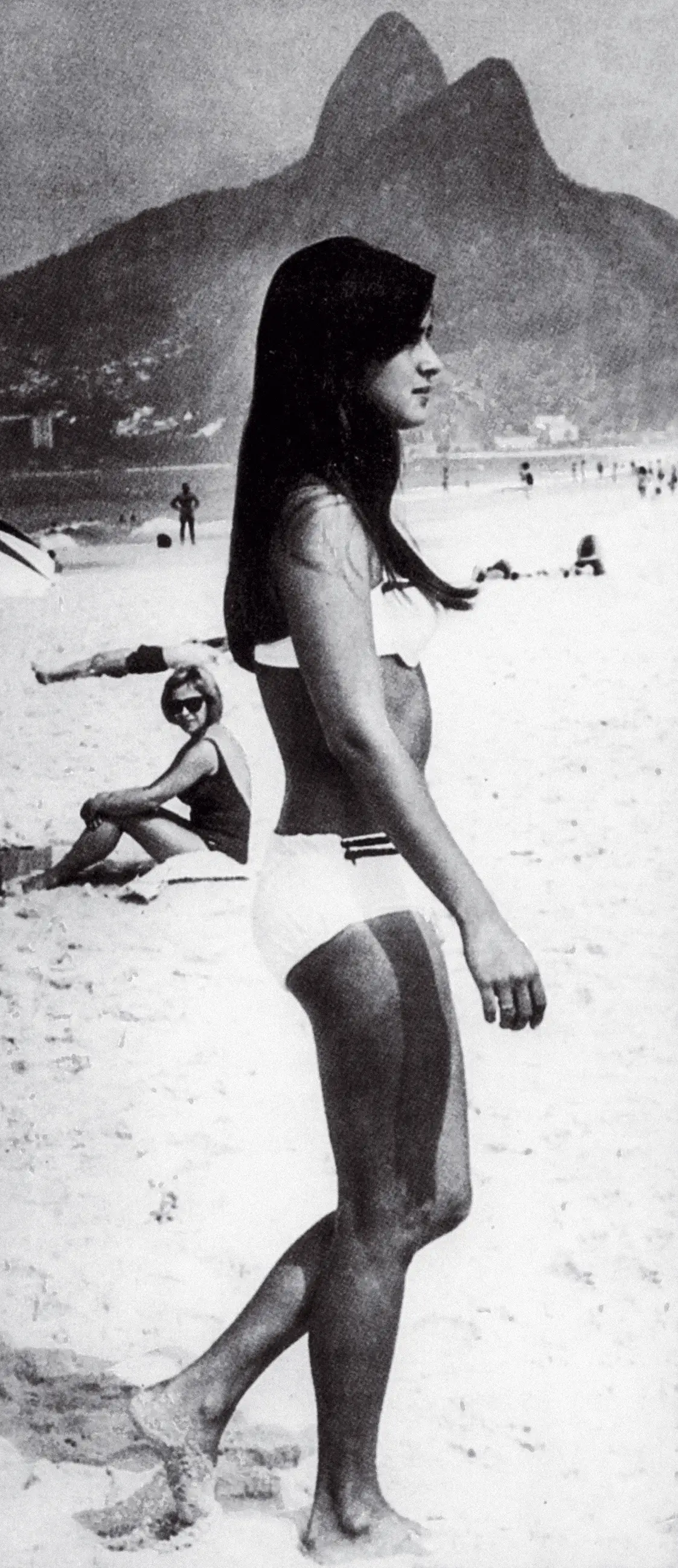

A Miami, dans un stade gigantesque, j’ai assisté quelques jours plus tard à des scènes de tragédies antiques, émouvantes à en pleurer. Les milliers de sièges du stade étaient occupés par des familles cubaines vivant aux Etats-Unis et, de jour comme de nuit, arrivaient de l’aéroport des autobus qui déposaient leurs occupants débarqués de Mariel (en ce seul mois de mai 1980, ils furent 86 000).

Ils étaient accueillis dans le stade sous les bravos. Puis, dans le silence revenu, un speaker énonçait ces noms interminables dont le castillan a le secret, ces Maria de la Luz Martinez de Sanchez, ou ces José-Maria Antonio Perez Rodriguez.

Et soudain, un cri dans un coin du stade, le faisceau lumineux des télés pointé vers un groupe de gens sautant en l’air de joie puis dévalant les escaliers du stade pour tomber dans les bras des cousins ou frères et sœurs retrouvés.

La stratégie de Fidel Castro

Cet exode des Marielitos a commencé par un coup de force. Le 5 avril 1980, 10 000 Cubains entrent dans l’ambassade du Pérou à La Havane et demandent à ce pays de leur accorder asile.

Dix jours plus tard, Castro déclare que ceux qui veulent quitter Cuba peuvent le faire à condition d’abandonner leurs biens et que les Cubains de Floride viennent les chercher au port de Mariel.

L’hypothèse est que Castro voit dans cette affaire une double opportunité :

- Il se débarrasse d’opposants -il en profite également pour vider ses prisons et ses asiles mentaux et sans doute infiltrer, parmi les réfugiés, quelques agents castristes ;