Tu ne convoiteras point la femme de ton prochain; tu ne désireras point la maison de ton prochain, ni son champ, ni son serviteur, ni sa servante, ni son boeuf, ni son âne, ni aucune chose qui appartienne à ton prochain. Deutéronome 5: 21

Tu l’aimes, parce que tu sais que je l’aime. Shakespeare (Sonnet 42)

Ô enfer, choisir l’amour par les yeux d’un autre ! Shakespeare

Il arriverait, si nous savions mieux analyser nos amours, de voir que souvent les femmes ne nous plaisent qu’à cause du contrepoids d’hommes à qui nous avons à les disputer, bien que nous souffrions jusqu’à mourir d’avoir à les leur disputer ; le contrepoids supprimé, le charme de la femme tombe. On en a un exemple douloureux et préventif dans cette prédilection des hommes pour les femmes qui, avant de les connaître, ont commis des fautes, pour ces femmes qu’ils sentent enlisées dans le danger et qu’il leur faut, pendant toute la durée de leur amour, reconquérir ; un exemple postérieur au contraire, et nullement dramatique celui-là, dans l’homme qui, sentant s’affaiblir son goût pour la femme qu’il aime, applique spontanément les règles qu’il a dégagées, et pour être sûr qu’il ne cesse pas d’aimer la femme, la met dans un milieu dangereux où il lui faut la protéger chaque jour. (Le contraire des hommes qui exigent qu’une femme renonce au théâtre, bien que, d’ailleurs, ce soit parce qu’elle avait été au théâtre qu’ils l’ont aimée. Proust

Vous nous avez fait faire tout ce chemin pour nous montrer quoi: un triangle à la française ? Eglinton (Ulysse, James Joyce)

Elle était belle comme la femme d’un autre. Paul Morand

Le système de l’amour du prochain est une chimère que nous devons au christianisme et non pas à la nature. Sade

Il me semblait même que mes yeux me sortaient de la tête comme s’ils étaient érectiles à force d’horreur. Georges Bataille

What are those voices outside love’s open door make us throw off our contentment and beg for something more? Don Henley

Si le Décalogue consacre son commandement ultime à interdire le désir des biens du prochain, c’est parce qu’il reconnait lucidement dans ce désir le responsable des violences interdites dans les quatre commandements qui le précèdent. Si on cessait de désirer les biens du prochain, on ne se rendrait jamais coupable ni de meurtre, ni d’adultère, ni de vol, ni de faux témoignage. Si le dixième commandement était respecté, il rendrait superflus les quatre commandements qui le précèdent. Au lieu de commencer par la cause et de poursuivre par les conséquences, comme ferait un exposé philosophique, le Décalogue suit l’ordre inverse. Il pare d’abord au plus pressé: pour écarter la violence, il interdit les actions violentes. Il se retourne ensuite vers la cause et découvre le désir inspiré par le prochain. René Girard

Jacopo Sansovino, avec son rare talent, ornera votre chambre d’une Vénus si vraie et si vivante qu’elle emplira de concupiscence l’âme de tout spectateur. L’Arétin (auteur de sonnets pornographiques, lettre à Federigo Gonzague de Mantoue, 1527)

Titien a presque terminé, sur commande de Monseigneur, un nu qui risquerait d’éveiller le démon même chez le cardinal San Silvestro. Le nu que Monseigneur a vu à Pesaro dans les appartements du duc d’Urbino est une religieuse à côté d’elle. L’Arétin (Lettre au cardinal Alessandro Farnese, 1544)

Je vous jure, Monseigneur, qu’il n’existe pas d’homme perspicace qui ne la prenne pour une femme en chair et en os. Il n’existe pas d’homme assez usé par les ans, ni d’homme aux sens assez endormis, pour ne pas se sentir réchauffé, attendri et ému dans tout son être. Ludovico Dolce (1564)

Les toiles de Titien et les Sonnets luxurieux de l’Arétin ont la même raison – érotique – d’être. Mais, à la différence de ces sonnets, les nus de Titien peuvent sembler répondre à l’exigence du Livre du Courtisan de Baldassar Castiglione, livre de chevet de l’empereur Charles Quint, livre qui régit les convenances de toutes les cours : « Pour donc fuir le tourment de cette passion et jouir de la beauté sans passion, il faut que le Courtisan, avec l’aide de la raison, détourne entièrement le désir du corps pour le diriger vers la beauté seule, et, autant qu’il le peut, qu’il la contemple en elle-même, simple et pure, et que dans son imagination il la rende séparée de toute matière, et ainsi fasse d’elle l’amie chérie de son âme. Pascal Bonafoux

En 1974, un accident de la circulation impliquant le président Giscard d’Estaing, qui conduisait lui-même une voiture aux côtés d’une conquête, au petit matin dans une rue de Paris avait fait les titres de la presse satirique. (…) Mitterrand, entre deux dossiers, consacrait beaucoup de temps à son harem. Chirac nommait ses favorites au gouvernement. Ses disparitions nocturnes entraînaient l’inévitable question de Bernadette : « Savez-vous où est mon mari ce soir? » C’est ainsi: en France, sexe, amour et politique sont indissociables. Sexus Politicus

Monsieur le président, mesdames les ministres, cet amendement concerne l’article 206 du code civil. J’évoquais tout à l’heure Jaurès. Je souhaite maintenant convoquer les mânes de Courteline, Feydeau, Labiche et Guitry. Pourquoi ? Parce qu’en transformant l’article 206, mes chers collègues, vous supprimez la belle-mère ! Vous supprimez un personnage essentiel de leur théâtre ! Vous portez un coup terrible au théâtre de boulevard ! La belle-mère disparaît ! Marc Le Fur (député UMP, débat parlementaire sur la suppression des mots « père » et « mère », 05.02.13)

Les sorties de l’Elysée en direction d’un souterrain où l’attendaient un scooter et un casque intégral, les séjours rue du Cirque (cela ne s’invente pas) semblent sortir d’une comédie de boulevard ou d’un vaudeville. La France est passée en quatre décennies d’un Président qui sortait de l’Elysée en petite voiture discrète pour aller voir ses maîtresses, et qui pouvait heurter le camion du laitier à l’aurore à un Président polygame entretenant sa deuxième famille aux frais du contribuable, avant que vienne le célèbre monsieur « trois minutes douche comprise ». Elle a échappé au priapique du Sofitel de New York pour avoir le premier Président non marié et acteur burlesque à ses heures, dans le rôle « je trompe ma femme, mais elle ne le sait pas, d’ailleurs ce n’est pas ma femme ». Ce Président a voulu le mariage pour les homosexuels, mais surtout pas pour lui-même. Guy Millière

L’éventail proposé dans Benefits Street est large : il y a la mère de famille polonaise qui élève seule ses deux enfants et tente de trouver un boulot, un couple de 22 et 23 ans avec deux enfants qui ne travaille pas, une famille de 14 Roumains, récemment installés, qui inspectent les poubelles pour trouver du métal afin de le revendre, le vieil alcoolique revendiqué qui explique fièrement «être la vedette du programme et avoir inventé le titre» et affirme utiliser ses allocations pour nourrir son chien et acheter ses bouteilles. Bref, on plonge droit dans le cliché complet de ce que certaines critiques – et elles sont nombreuses – ont qualifié de « pornographie de la pauvreté ». Libération

Après le mariage, le vaudeville pour tous !

A l’heure où, oubliant le double accident qui entre le rejet de Sarkozy et la défection de DSK l’avait fait, l’actuel maitre de la synthèse qui nous tient actuellement lieu de président vient de rappeler au monde l’une des plus grandes contributions du pays de Sade et de Bataille à la compréhension de la nature humaine, à savoir le fameux « French triangle » de nos célébrissimes pièces de boulevard …

Et en ces temps du tout est permis où le terme de pornographie ne peut plus guère qualifier que le rappel de la pauvreté …

Pendant que, du yoga nu aux mannequins aux poils pubiens, nos cousins américains rivalisent d’ingéniosité pour contourner les nouveaux interdits du « male gaze » des féministes et du NSFW de leurs employeurs …

Comment ne pas voir derrière les efforts titienesques de nos premiers grands peintres il y a quelque 500 ans pour tenter de légitimer, entre vénus et marie-madeleines, leur célébration du corps humain et surtout féminin …

Et, du voyeurisme (autre importante contribution lexicale française au monde) au contrepoids proustien ou à la pulsion scopique freudienne ou au miroir lacanien, derrière les efforts non moins titanesques de nos romanciers et de nos cliniciens …

La vérité, longtemps oubliée depuis l’avertissement multimillénaire du dixième commandement mais retrouvée et théorisée récemment par René Girard, de la nature intrinsèquement triangulaire du désir humain …

Autrement dit, comme le rappelle si efficacement, le titre morandien d’un film (français) qui vient de sortir sur nos écrans, qu’aucune femme n’est jamais aussi belle que la femme d’un autre ?

To NSFW or not to NSFW? (now SFW)

Roger Ebert

October 31, 2010

This entry is safe for work.

I hesitated just a moment before including Miss June 1975 in my piece about Hugh Hefner. I wondered if some readers would find the nude photograph objectionable. Then I smiled at myself. Here I was, writing an article in praise of Hefner’s healthy influence on American society, and I didn’t know if I should show a Playmate of the Month. Wasn’t I being a hypocrite? I waited to see what the reaction would be.

The Sun-Times doesn’t publish nudes on its site, but my page occupies a sort of netherland: I own it in cooperation with the newspaper, but control its contents. If anyone complains, I thought, it will be the paper, and if they do I’ll take it down.

You dance with the one that brung you. But no one at the newspaper said a word, even though they certainly saw the page because the same article also appeared in the Friday paper. Hefner was in town for the weekend for a nostalgic visit to his childhood home, and a screening at the Siskel Film Center of the new documentary about his life . He’s a local boy who made good.

At first no one at all objected to the photo, even though the entry was getting thousands of hits. It went online early on Sunday afternoon. But Monday was a workday, and a reader asked if it had occurred to me to label it NSFW (« not suitable for work »). The thought may have crossed my mind, but come on, would anybody be surprised to find a nude somewhere during a 2,200-word piece on Hef? It wasn’t like I was devoting a whole page to it; I embedded it at a prudent 300 pixels. Like this:

Sorry. After learning that the mere presence of this photograph could get you fired and my blog put on a restricted list, I have removed the « prudent 300 pixels » and linked the photograph here.

Then other readers started wondering about a NSFW warning. They weren’t objecting to the photo; indeed, no one ever did, even some readers who felt Hefner had been a pernicious influence on the world. Feminist readers, some well known and respected by me, spoke of his objectification of the female body, his misuse of the Male Gaze, and so on. But no one objected to the photo itself. No, they explained that they read the column at work (« during lunch break, » of course) and were afraid a supervisor or co-worker might see a nude on their monitor. I asked one of these readers if his co-workers were adults. Snark.

As a writer, it would have offended me to preface my article with a NSFW warning. It was unsightly — a typographical offense. It would contradict the point I was making. But others wrote me about strict rules at their companies. They faced discipline or dismissal. Co-workers seeing an offensive picture on their monitor might complain of sexual harassment, and so on. But what about the context of the photo? I wondered. Context didn’t matter. A nude was a nude. The assumption was that some people might be offended by all nudes.

This was a tiny version of this photograph. When will we grow up?

I heard what they were saying. I went in and resized the photo, reducing it by 2/3, so that it was postage-stamp 100 pixel size (above) and no passer-by was likely to notice it. This created a stylistic abomination on the page, but no matter. I had acted prudently. Then I realized: I’d still left it possible for the photo to be enlarged by clicking! An unsuspecting reader might suddenly find Miss June 1975 regarding him from his entire monitor! I jumped in again and disabled that command.

This left me feeling more responsible, but less idealistic. I knew there might be people offended by the sight of a Playmate. I disagreed with them. I understood that there were places where a nude photo was inappropriate, and indeed agree that porn has no place in the workplace. But I didn’t consider the photograph pornographic. Having grown up in an America of repression and fanatic sin-mongering, I believe that Hefner’s influence was largely healthy and positive. In Europe, billboards and advertisements heedlessly show nipples. There are not « topless beaches » so much as beaches everywhere where bathers remove swimsuits to get an even tan.

At Cannes you see this on the public beach, and pedestrians nearby on the Croisette don’t even stop to notice. Ironically, the only time you see a mob of paparazzi is when some starlet (on the Carlton Hotel pier say), is making a show of removing her clothes. Then you have a sort of meta-event, where paparazzi are photographing other paparazzi photographing this event. It’s all a ritual. The clothes come off, the photographers have a scrum, everyone understands it’s over, and the paparazzi leave, sometimes while the starlet is still standing there unadorned. In Europe, people know what the human body looks like, and are rather pleased that it does.

America has a historical Puritan streak, and is currently in the midst of another upheaval of zeal from radical religionists. They know what is bad for us. They would prefer to burn us at a metaphorical stake, but make do with bizarre imprecations about the dire consequences of our sin. Let me be clear: I am not speaking of sexual behavior that is obviously evil and deserves legal attention. But definitions differ. Much of their wrath is aimed at gays. I consider homosexuality an ancient, universal and irrefutable fact of human nature. Some radicals actually blamed it for 9/11. For them the ideal society must be Saudi Arabia’s, which I consider pathologically sick.

When we were making « Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, » I got to know Cynthia Myers and Dolly Read (above), the two Playmates in the film, and have followed them through the years. They have good memories of the experience. I am in touch with Marcia McBroom, the actress who played the third of the movie’s rock band members. She is a social activist, loves the memory of her Hollywood adventure, and recently sponsored a benefit showing of BVD for her Africa-oriented charity, the For Our Children’s Sake Foundation. These women looked great in the 1970s and they look great today, and let me tell you something I am very sure of: We all want to look as great as we can.

Now back to the woman in the photograph. Her name is Azizi Johari. She went on after her centerfold to have some small success in motion pictures, most notably in John Cassavetes’ « The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. » Today she would be in her 50s and I hope is pleased that such a beautiful portrait of her was taken. A reader sent me a link to Titian’s 16th century painting « Venus of Urbino » (below), and suggested to me that this was art and Miss Johari’s photograph was not. I studied them side by side. Both women are unclothed, and regard the viewer from similar reclining postures on carefully-draped divans. I looked at them with the Male Gaze, which I gather that (as a male) is my default Gaze. I want to be as honest as I can be about how these two representations affect me.

Let us assume that the purpose of both artworks is to depict the female form attractively. Both the photographer and the painter worked from live models. Titian required great skill and technique in his artistry. So did the photographer, Ken Marcus, because neither of these portraits pretends to realism. Great attention went to the lighting, art direction and composition of the photograph, and makeup was possibly used to accent the glowing sheen of Miss Johari’s skin. I would argue that both artworks are largely the expressions of imagination.

For me, Miss Johari is more beautiful than Venus. She strikes me as more human. She looks at me. Her full lips are open as if just having said something. Her skin is lustrous and warm. Venus, on the other hand, seems to have her attention directed inward. She is self-satisfied. She seems narcissistic, passive, different. Johari is present. She seems quietly pleased to suggest, « Here I am. This is me. » Wisely she avoids the inviting smile I find so artificial in « pin up » photography. She is full of her beauty, aware of it, it is a fact we share. Venus is filled by her beauty, cooled by it, indifferent to our Gaze. If you were to ask me which is the better representation of the fullness of life, I would choose Johari.

Of course abstract artistic qualities are not the point of either work. The pictures intend to inspire a response among their viewers. For men, I assume that is erotic feeling. Women readers will inform me of the responses they feel. Homosexuals of both sexes may respond differently. They will tell me.

For me? Miss June is immediately erotic. I regard first of all her face, her eyes, her full lips and then her breasts, for I am a man and that is my nature. I prefer full lips in women, and hers are wonderful. I admire full breasts. Hers are generous but manifestly natural. The female breast is one of the most pleasing forms in all of nature, no doubt because of our earliest associations. I dislike surgical enhancements. As my friend Russ Meyer complained in the early days of silicone, « It misses the whole principle of the matter. »

Miss Johari’s arms and legs are long and healthy, she is trim but not skinny, she is not necessarily posing with her left arm but perhaps adjusting a strand of hair. I find the dark hue of her skin beautiful. Photographs like this (she was the fifth African-American Playmate) helped men of all races to understand that Black is Beautiful at a time when that phrase came as news to a lot of people. In a blog about her, I find she was « the first black Playmate to have distinctly African features. » Another entry could be written about that sentence.

As for Venus of Urbino, she has no mystery at all. I look at her and feel I know everything, and she thinks she does too. She gives no hint of pleasure or camaraderie. If you tickled her with a feather, she would be annoyed. Miss Johari, I imagine, would burst into laughter and slap the feather. I can see myself having dinner with her. To have dinner with Venus would be a torment. My parting words would be, « This bill is outrageous! I wouldn’t pay it if I were you! »

Of course these are all fantasies. I know nothing about either model. That is what we do with visual representations of humans; we bring our imaginations to them. It’s the same with movies. The meaning is a collaboration between the object and the viewer. That is how we look at pictures, and how we should. If it seems impertinent of my to compare the photograph with the painting, the best I can do i quote e. e. cummings:

mr youse needn’t be so spry

concernin questions arty

each has his tastes but as for i i likes a certain party

gimme the he-man’s solid bliss for youse ideas i’ll match youse

a pretty girl who naked is is worth a million statues

Now as to the problem of the workplace. I understand there will be pictures on a computer screen that will be offensive. I get that. Why will they be offensive? Perhaps because they foreground a worker’s sexual desires, and imply similar thoughts about co-workers. Is that what’s happening with the blog entry on Hefner? Is anyone reading it for sexual gratification? I doubt it. That’s what bothers me about so many of the New Puritans. They think I have a dirty mind, but I think I have a healthy mind. It takes a dirty mind to see one, which is why so many of these types are valued as censors or online police.

The wrong photographs on a screen might also suggest a blanket rejection of the values of the company. Some corporations require an adherence to company standards that is almost military. Sex has a way of slicing through all the layers of protocol and custom and revealing us as human beings. But lip service must be paid to convention.

We now learn that the recent Wall Street debacle was fueled in part by millions spent on prostitution and drugs. We have seen one sanctimonious politician and preacher after another exposed as a secret adulterer or homosexual. I don’t have to ask, because I guess I know: If an employee in the office of one of those bankers, ministers or congressman had Azizi Johari on his screen, he would be hustled off to the HR people.

I haven’t worked in an office for awhile. Is there a danger of porn surfing in the workplace? Somehow I doubt it. There is a greater danger, perhaps, of singling out workers for punishment based on the zeal of the enforcers. And of course there is always this: Supervisors of employee web use, like all employees, must be seen performing their jobs in order to keep them.

There is also this: Perfectly reasonable people, well-adjusted in every respect, might justifiably object to an erotic photograph on the computer monitor of a coworker. A degree of aggression might be sensed. It violates the decorum of the workplace. (So does online gaming, but never mind.) You have the right to look at anything on your computer that can be legally looked at, but give me a break! I don’t want to know! I also understand that the threat of discipline or dismissal is real and frightening.

I’ve made it through two years on the blog with only this single NSFW incident. In the future I will avoid NSFW content in general, and label it when appropriate. What a long way around I’ve taken to say I apologize.

Voir aussi:

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

04 January 2003

Very little is recorded of the life of the great Renaissance artist Titian. What we do know of his personality and his turbulent sexuality is laid bare in his painting

He could not help looking. It was an accident – well, all right, an accident combined with curiosity. But what was a man to do? Actaeon, the story goes, was out hunting with his friends in the woods when he got lost. That was his only mistake, really – that and looking at a naked goddess. « There is nothing sinful in losing one’s way, » points out the ancient Roman poet Ovid, who tells the story of Actaeon in his fabulist poem Metamorphoses, written 2,000 years ago.

The grandson of Cadmus had hunted all morning with his friends, and their nets and swords were dripping with blood, when Actaeon suggested they call it a day and enjoy the noon heat. He himself wandered off from the sweaty mob into a thickly overgrown valley, and found a cave. It was a beautiful and refreshing place, entered via a graceful arch, and inside there was cold, clear water, flowing from a spring into a deep pool where Diana, goddess of the hunt, liked to come to cool off when she was tired from shooting her bow and hurling her javelin. Here she was, accompanied by her nymphs, who took her weapons and her clothes so that, naked, unencumbered, she could bathe. And that was when Actaeon blundered in.

Did his eyes fix on her breasts, her thighs? Or did he try not to look? Diana didn’t care if he was guilty or innocent. She was a modest goddess. She hadn’t got her bow, so instead she threw water – magic water – in the young fool’s face, yelling at him, « Now go and tell everyone you saw Diana naked – if you can! » Actaeon was growing antlers, his face was turning furry. Diana turned him into a stag – a dumb male animal, his phallic antlers useless when what he needed, and no longer had, was a voice to tell his hunting dogs it was him, their master, Actaeon, that they were hunting down.

In Titian’s painting The Death Of Actaeon, the dogs have just caught up with their hapless master. They are good, zealous dogs, doing what they were trained to do. In a line of energy, they fly at him – the three pack leaders are already on him. In Titian’s version, some details of Ovid’s story are changed in a way that brilliantly simplifies and intensifies the action, and heightens its emotion. Titian’s Actaeon has the body of a burly man; only his head has changed into that of a very stupid-looking stag, like a dead, stuffed trophy fixed on to his shoulders. The strangest thing about Actaeon’s head is that you can barely see his eye on the profile facing us; Titian – who painted the reflective depths of eyes as well as anyone in history – has chosen here to blind Actaeon in a painterly equivalent to Ovid’s robbing him of speech.

Titian’s painting has humour – it’s a blackly comic tale of voyeurism punished, and Titian relishes Diana’s mighty presence in a way that’s joyous and celebratory – but it is also heartfelt, sombre, magnificently piteous. The tragedy is in the trees. They are yellow and brown and seared and autumnal; these are not the fresh, green trees of youth, but the tired woods of age, decay; it is as if Actaeon’s youth has sped into senescence as the life not lived flashes in front of him. And yet those trees are lovely; the matted texture of them is so deliberately thick and rough that you can feel it on your skin, on your face. You can feel the stormy air, too, the chill breeze before the storm that those roiling clouds and that terrific sky – eerily turning from grey to yellow – promise.

It was said that Tiziano Vecellio was 104 years old when he died in 1576. This was probably an exaggeration, but an understandable one – 500 years ago, living beyond your 30s was an achievement. The one rival to Titian’s crown as the supreme genius of Renaissance Venice – the romantic, turbulent Giorgione – died of plague as a young man in 1510, after less than a decade’s work. Titian outlived him, and the average life span, by 10, 20, 30 . . . eventually, in that world, you lost count. He was probably born in the 1480s, making him between 86 and 96 when he died. Which means that Titian was at least in his 60s when he wrote to Philip II of Spain in June 1559, telling him he had « two poesie already under way: one of Europa on the Bull, the other of Actaeon torn apart by his own hounds ».

Actaeon never got to Spain; it never joined the collection commissioned by Philip II from Titian, illustrating myths from Ovid. Instead, it seems to have stayed in his studio, possibly until his death. It is a chromatically muted painting – very different from the erotic, visual banquets of Titian’s other poesie; some say that it is unfinished, that it would have eventually looked much brighter. But I think the lack of finish is telling. The Death Of Actaeon seems to me a fearsomely personal work. It is one of those paintings in which Titian speaks about himself: he is Actaeon. An Actaeon grown old, a frenzied animal at the mad mercy of his eye, his roving, incredible eye.

About his greatness there has never been any doubt – not since he painted his astonishing altarpiece of the Assumption in the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice as an up-and-coming contender in 1516-18. The Frari is a gothic church, high and bare, its glory a tall, semicircular network of arched windows that turns its south-west wall into a broken dazzle of sunlight. Insanely, the ambitious Titian accepted a commission to make an altar painting to stand in front of this wall of light – a painting that was doomed to be cast into a deep shadow, to seem a mere eccentric, dull daub against the sun that shone above and around it.

Titian’s painting meets the sun on equal terms. It is so bright, the gold heaven towards which the Virgin Mary is raised on a cloud borne by putti is so luminous, that instead of being overpowered by the sunlight streaming above, it seems that the sun is paying its compliments to Titian. Look more closely, and it turns out that Titian has tricked the eye by mimicking the contrast of light and shade that threatens to dull his painting. Down at the bottom of the seven metre tall panel, at our level, the disciples – as we do – look up at the ascending Virgin; they are in shade in a dowdy space. At the very centre of the earthbound crowd is a black hole. Up above, the heavenly gold light Mary enters is a shining circle, its circumference clearly defined by angels’ faces, and it gets whiter towards the centre: it is a depiction of the sun. Seeing how this light outshines the cooler colours below, we somehow accept that this painted sun is as powerful as the real one. Titian is a magician, and this is his most jaw-dropping sleight of hand.

No one has ever questioned that this is one of the world’s indispensable works of art; and no one has ever questioned Titian’s stature. He is the painter’s painter, and he is also the prince’s painter (not to mention, as he was nicknamed, the Prince of Painters); he is the expert’s painter and the people’s painter; he has never gone out of fashion, not in his lifetime, not ever. His art is endlessly fresh and generative. Even when they parodied him – Manet’s Olympia is a travesty of Titian’s Venus Of Urbino – artists learned from him, studied him, were inspired by him.

The three most influential post-Renaissance painters, Velázquez, Rubens and Rembrandt, were devoted to Titian – Rembrandt modelled one of his own self-portraits on Titian’s Portrait Of A Man (with a blue sleeve) in the National Gallery; Velázquez learned his luxurious style from Titians in the Spanish royal collection; Rubens copied many of his paintings. More than anyone else, Titian shaped our idea of painting – what it is, what it is capable of.

When he was young, oil painting was a new idea, and it was used with a raw excitement, as if every painting were a scientific discovery – the first time a landscape was depicted in convincing perspective, the first accurate painting of a reflection. When Titian died, oil painting had grown up – it had at its command an incredible array of techniques, an empire of the visual. It was Titian who created this empire. It was Titian who demonstrated the full range of powers specific to painting on canvas – to be at once a convincing imitation of appearances and also something else, something abstract. At the same time he displayed painting’s sensuality: when the American artist Willem de Kooning said oil paint was invented to depict flesh, it must have been Titian (and his disciple, Rubens) he was thinking of. Today, it is possible to argue that Titian was the most influential painter in history. And because his painterliness has an abstract quality, he has continued to influence modern artists. In the 19th century, Delacroix took Titian’s colour into realms of romantic madness – his Death Of Sardanapalus is a psychotic riff on Titian – and Degas took up his cult of the flesh. Even today, the best living painters, Gerhard Richter (who has done versions of Titians) and Lucian Freud, echo different aspects of Titian.

Titian is part of a triumvirate, with Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti, who invented the very idea of the modern artist. Da Vinci and Michelangelo, in their refusal to complete commissions and, in Michelangelo’s case, his stroppiness, established the image of the self-pleasing, wilful genius; Titian, partly because of his long career, but mostly through his dominance of a Europe-wide art market in which kings and princes collected his work for decades, established the authority of painting. He once dropped his brush in the presence of Emperor Charles V, and it was the Emperor who insisted on picking it up in deference to Titian.

And yet, he wears a mask. He lived for perhaps 90 years, in the most sophisticated city in the world, and he was famous from his 20s onwards. He was by all accounts an articulate, courtly, sociable man, a close friend of the writers Ariosto and Aretino, bright enough to be sent on diplomatic missions on behalf of the Venetian Republic, refined enough to become the companion of kings. And yet behind the screen of constant, smooth success, his life is practically unknown. His work, because of that, retains an enigmatic distance. The Frari altarpiece is Venice’s answer to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel; and yet it’s nothing like as touristed because Titian doesn’t have the charisma of Michelangelo, his Florentine contemporary. Titian’s personality doesn’t burst out of the past like Michelangelo’s.

Titian never said anything quotable, but Michelangelo said something quotably mean about Titian. In the 1540s, Titian worked for a while in Rome. There, Michelangelo visited his studio. Titian had just finished his painting of Danaë – illustrating another tale from ancient mythology, in which the god Jupiter takes the form of a shower of gold to make love to Danaë. He did several versions of the painting – but the one Michelangelo saw is the best (part of the Capodimonte Museum exhibit in Naples, it is coming to the National Gallery’s Titian exhibition). It is the erotic pendant to Titian’s Frari altarpiece; just as he creates his own blazing sun in the Frari, here he makes flesh and gold merge in an uncanny, inexplicable bit of magic – a painting that is at once sensual and mystical, or rather, that is mystical about the senses.

As in the Frari, it is the play of light and darkness that weaves a spell. On her bed, the naked Danaë is warmed by subtly golden light. Titian captures the richness rather than the vulgarity of gold: that is also true of the almost bronze cloud, flecked with coins, that looms above Danaë in a dark, dense interior. The void of darkness at the centre makes the scene incomplete, luring the viewer to complete it; the imagination does this by abstracting and fusing the colours of skin and gold, that hang in memory as a dream, a vision of desire beyond verbal expression.

After seeing this incredible painting, Michelangelo praised the painting to Titian’s face. When he left the studio, however, he commented that it was very nice, its colouring was very nice – but it was a pity that Titian couldn’t draw.

Michelangelo’s put-down is the most celebrated expression of the fundamental difference between Florentine and Venetian art: while Tuscan Renaissance artists believed that line came first, Venetian painting defines space by colour, and it is in his colours that Titian’s personality will be found, in the texture of his paint. Titian’s paintings are not designed, then filled in; they exist in total spontaneity, in the brushing that Titian makes visible. His paintings are not smooth; he paints on rough canvas in which paint catches; and he pursues the same emotive, personal themes across his long career. Titian was a high-class kind of guy; his friend, the poet Aretino, commented on how Titian always knew how to speak to a lady, kissing hands, making courtly jests. And there’s a pleasure in civilised restraint – or, perhaps, a need for it – that distinguishes his art. This comes out most profoundly in his love of genre.

Titian, I think, enjoyed the discipline of objective rules – for example the conventions of portraiture – which he could then stretch, challenge, reinvent. His incredibly lifelike Portrait Of A Man (with a blue sleeve), painted in 1512, which may be a self-portrait, is an example of this. Titian’s joy as an artist in this painting is purely technical; he reinvents the repertoire of poses available to painters. Doing something stylish, Titian communicates something personal – the deeply felt presence of this unnamed 16th-century man.

Titian’s most accomplished genre of all is the one he himself invented or helped to invent – that of erotic mythology. There had been classical mythological paintings in Italy since the 15th century, but the kind of narrative, Ovidian art for which Titian is famous was new; it was his genre, the « poesie », as he called his paintings for Philip II. If genre is a discipline, and literary subject matter is an objective constraint, what Titian gave himself when he developed his unique kind of narrative painting was a way of both restraining and at the same time releasing – in a stylised, mediated way – his own sexuality. It is as if he was so obsessed with eroticism, so obsessed with women – like Picasso in his sometimes loving, sometimes hateful portraits – that he had to invent a new art of organised fantasy, of civilised eroticism.

Because the fantasies that Titian painted, from early on, are not just the lovingly painted, perhaps slightly complacent images of bountiful, sexually generous women, such as his Venus Of Urbino in the Uffizi – a painting that strikes you as pure body, openly desired by the artist. Or his dreamlike Le Concert Champêtre in the Louvre, once attributed to Giorgione, in which the same woman – depicted twice, including from behind, as if Titian wanted to record her entire physical presence – is the unashamedly naked attendant, the sexy yet docile companion, of two fully dressed men (this is a another picture Manet parodied – Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe).

Titian loved women – this has to be the least debatable statement in the history of art. This wasn’t just sex. He painted women as heroic and strong social actors – his portrait known as La Schiavona in the National Gallery stands above a marble relief of her own face, making her resemble a proud Roman matron, and she’s a big, forceful character. And the most brilliant of all Titian’s portraits, the most lovingly alive, is his dignified picture of a two-year-old girl, Clarissa Strozzi.

Titian’s emotional life pervades his paintings. Far from coming easily, the civilised tone of his art seems hard-won – violence, rage, terror are frothing in his brushwork. His overriding eroticism is not something worked up for patrons – although there was obviously a market for paintings like « the nude lady », as the man who commissioned it called the Venus Of Urbino – but something in him which painting allows him to project, simultaneously to enjoy and control.

Through his career, he is drawn to fierce and violent images. In his very first major public commission, a series of frescoes in Padua, he includes a scene of shocking brutality: the story of a jealous husband who murdered his wife. She begs for mercy while he prepares to stab her a second time. Later, Titian did several paintings of The Rape Of Lucretia, including a late, expressionistic work comparable to The Death Of Actaeon.

None of this is to say that Titian’s paintings are misogynist, hateful or hypocritical – on the contrary. There is a stale view of paintings such as the Venus Of Urbino, which arises from their popularity in the 19th century, as mildly saucy soft porn. In reality, and this is the source of his power, Titian’s sexuality is complicated, emotional, tortured and alive; his paintings embody the desires and terrors of a man who was capable of acute jealousy, anger, and a kind of religious worship of women.

Titian’s paintings of women are personal in another way. The same models recur in many of his pictures. One group of paintings seems to depict a woman who – a flower she holds suggests – may have been called Violante. It used to be said she was his lover and the pictorial evidence makes that romantic Victorian idea very plausible. The woman who posed as Flora, Titian’s most iconic beauty, is also in his painting Sacred And Profane Love. Flora is interpreted in all kinds of ways – as the goddess Flora, as a Venetian courtesan, as an image of correct sexual behaviour in a Venetian marriage – but the intimacy and warmth and passion of this painting (which is coming to the National Gallery from the Uffizi in Florence) might actually be Titian’s, and her, secret. Many of his most erotic paintings may be games in which Titian paints monuments to his lovers under the guise of heady mythological and pastoral art. It has even been suggested that Flora is Titian’s mistress Cecilia, whom he finally married in 1525 to legitimise their children.

Titian, so quiet about himself and so organised in his professional career, is in reality a powder keg of emotion, artfully channelled but never suppressed; his art is profoundly confessional. The Death Of Actaeon is a confession. And at the end of his life, Titian movingly drops all his elaborate strategies, takes off his Venetian mask and addresses us – and his God – directly in one of the most unguarded paintings anywhere. Only a master of irony could make such a total confession; only a master of colour could make a painting that is so denuded of it: Titian’s Pietà in the Accademia in Venice was painted as an ex-voto offering, a prayer, when Titian was very old and when Venice, the city he adored, was being devastated by plague. Titian’s Pietà pleads (the text is on a painted tablet) for mercy for Titian himself and for his son, Orazio. Titian puts himself in the painting, an almost naked, bearded old man, pathetically and hopelessly touching the hand of the dead Christ. Light has almost gone from the world – apart from a dull glow on the mosaic above Christ’s dimly shining corpse, the painting sinks into reveries of shadow, of death. If you look, you will eventually see what you fear, and in this last painting Titian sees death, his own death. Titian’s offering failed; neither he nor Orazio outlived the plague epidemic.

What is striking is that Titian, in his 80s, or 90s, or – who knows? – at the age of 104, so obviously wanted more life, more colour, more flesh. And looking at his paintings, so do we

· Titian is at the National Gallery, London WC2 (020-7747 5898), from February 19-May 18, 2003.

Voir également:

Italy’s Most Mysterious Paintings: Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love

Walks of Italy

November 29, 2012

Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love… a beautiful, and mysterious, painting in Italy!

Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love is the gem of Rome’s Borghese gallery… and one of the most famous paintings of Renaissance Italy. It’s so beloved, in fact, that in 1899, the Rothschild family offered to pay the Borghese Gallery 4 million lira for the piece—even though the gallery’s entire collection, and the grounds, were valued at only 3.6 million lira!

Perhaps the painting is so famous simply because of its beauty and because it’s a masterpiece by the Renaissance great Titian.

Or perhaps people have fallen in love with it because of its hidden secrets and symbolism—much of which art historians still don’t completely understand!

There’s a lot of mysterious stuff going on here.

At first glance, the painting might just look like another portrait of two lovely ladies, with a pastoral background behind them.

Look again.

First of all, there are the women themselves. One is clothed, bejeweled, and—seemingly—made up with cosmetics. She’s wearing gloves, and holding a plant of some kind. The other is (almost) stark naked, holding just a torch.

The church and pasture in Sacred and Profane Love

Then look at what they’re sitting on. That’s no carved-marble bench… that’s a sarcophagus. In other words, a coffin, of the type the ancient Romans used.

And it’s a strange sarcophagus, because it appears to be filled with water, which a cherubic baby is swirling.

Look even closer, and you can see a spout in the sarcophagus’ front, which the water is pouring out of and, seemingly, watering a growing plant below.

In the background, meanwhile, you have some other strange things going on: On our left, a horse and rider race up a mountaintop to a looming fortress, while two hares appear to be playing (or chasing each other); on our right, shepherds herd sheep in a pasture in front of a picturesque church, while a dog chases a hare.

Nothing that’s here is here by mistake. So what does it all mean?

We’re not sure. We have to rely on our knowledge of the painting’s symbols and hidden meanings to find out. And that’s because…

We don’t even know the real title of one of the most famous paintings in Europe

Although the piece is called Sacred and Profane Love, that’s not its original name. In fact, we don’t know what its original name was.

Here’s what we do know: Titian painted the piece in 1513-1514, at the age of just 25. And it was commissioned to celebrate the marriage of Niccoló Aurelio, a secretary to the Council of Venice, to Laura Bagarotto. No name is listed in the records for the painting, but in 1693, almost 200 years after it was painted, it showed up in the Borghese Gallery’s inventory under the name Amor Divino e Amor Profano (“divine love and profane love”).

…or what it’s supposed to show.

Sacred—or profane?

For a long time, art historians thought that the painting was supposed to show two different kinds of love: the sacred, and the profane.

It’s definitely safe to say the painting is about love. Symbols of love are scattered throughout, from the roses on the sarcophagus to the myrtle the woman on our left clasps (more on that later!). And, of course, the painting was a marriage gift, which would make this focus highly appropriate.

But does it show sacred and profane love? Well, if so, that might explain the background. The fortress, symbol of war and humanity, could symbolize the profane (or worldly); the church would, obviously, symbolize the sacred.

And it could explain the two women. Perhaps one is meant to be a Venus showing what worldly love looks like; the other, a Venus showing us sacred love.

But the interesting question is:

If this is true, then which of the two women represents sacred love, and which is the profane?

Is nudity actually a sign of the sacred? (Maybe!)

At first glance, you might think the woman on our left represents sacred love. After all, she’s clothed! The other, naked one would, of course, represent worldly, amorous love.

Some aspects of each woman’s costume do back up that theory, because there are so many hidden symbols here! For example, the clothed woman’s belt was generally considered a symbol of marital ties; and the myrtle in her hand symbolized the lasting happiness of marriage. On the other hand, the nude woman’s flame symbolized earthly lust.

But look again, and you see just as much symbolism pointing us in the opposite direction. For one thing, the clothed woman is seated, and therefore below—and closer to the earth than—her nude counterpart. She’s wearing gloves for falconry, or hunting, and holding a case of jewels, both signs of worldly pursuits. And she’s dressed very sumptuously (and not all that modestly!), with rich fabrics and even a touch of cosmetics.

But heavenly beauty doesn’t need any worldly adornment. The nude woman, therefore, might be sacred.

The key could be Cupid, mixing the waters in the sarcophagus…

Water swirls in the sarcophagus… and waters a growing plant?

Of course, that’s no baby between the two depictions of love (in this interpretation, two versions of Venus, goddess of love, herself): It’s Cupid. By mixing the waters in the well/sarcophagus, he might be suggesting that the ideal love is, in fact, a mix of these two kinds.

But this painting might not even be about sacred and profane love.

In the 20th century, art historian Walter Friedländer argued that the painting wasn’t about these two types of love at all. He thought it showed Polia and Venere, two characters in Francesco Colonna’s popular 1499 romance Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (don’t worry, there won’t be a test on that name!).

Another interpretation that’s much more simple… and makes a lot of sense? The painting could show the bride, Laura Bagarotto, herself, dressed in virginal white on the left. And the nude woman on the right? She might be Venus, initiating Laura into what love is like—complete with showing her the passion that’s necessary to make a marriage work (the torch).

But no one is sure what this painting really means. There’s a lot going on here, that’s for sure. And it’s kept art historians interested—and arguing!—for centuries.

Voir encore:

Titien ou l’art plus fort que la nature : être Apelle

Pascal Bonafoux

Ecrivain et critique d’art. Professeur d’histoire de l’art à l’université.

Clio

Le 5 janvier 1857 dans son Journal, Delacroix note : « Si l’on vivait cent vingt ans, on préférerait Titien à tout. » Cézanne affirme quant à lui : « La peinture, ce qui s’appelle la peinture, ne naît qu’avec les Vénitiens. » Cézanne songe à Titien comme il songe à Tintoret et à Véronèse. Peu lui importe que Titien ait près de trente ans, trente ans peut-être, lorsque naît Tintoret, qu’il ait dix ans de plus lorsque naît Véronèse en 1528. Ces regards de peintres sont essentiels. Parce qu’ils savent ce que « regarder », ce que « voir » veut dire. Parce qu’ils savent ce que « peindre » veut dire. Or la peinture est la seule vérité de Titien. Pour le reste…

Plus jeune en sa jeunesse, plus âgé en son vieil âge

Le 1er août 1571, Titien écrit à Philippe II pour réclamer des sommes qui lui sont dues. Il se dit dans cette lettre « serviteur du roi, maintenant‚ âgé de quatre-vingt-quinze ans ». Un émissaire espagnol, un certain Garcia Hernandez, dans un rapport daté du 15 octobre 1564, assure que Titien a près de quatre-vingt-dix ans. Raffaello Borghini écrit, quelques années après la mort du peintre, qu’il mourut en 1576 « à l’âge de quatre-vingt-dix-huit ou quatre-vingt-dix-neuf ans ». Ce qui confirme à peu près la même date… Titien serait né en 1477…

Dans le registre de la paroisse de San Canciano où meurt Titien le 27 août 1576, on inscrit son âge : cent trois ans. Titien serait né en 1473… Dans une lettre du 6 décembre 1567, Thomas de Cornoça, consul d’Espagne à Venise, affirme alors au roi que Titien a « quatre-vingt-cinq ans ». Titien serait né en 1482… Lorsqu’il lui rend visite en 1566, Vasari note que Titien a alors « environ soixante-seize ans ». Titien serait né en 1490… Dans le Dialogo della Pittura qu’il publie à Venise en 1557, Lodovico Dolce, qui est de ses amis, assure que lorsqu’il entreprit de peindre les fresques du Fondaco dei Tedeschi auprès de Giorgione en 1508, il « n’avait pas encore vingt ans ». Titien serait donc né en 1488…

1477, 1473, 1482, 1488, 1490 ?… Jeune, longtemps Titien a sans doute laissé entendre qu’il était plus jeune encore. Pour que l’on ne doute pas de sa précocité. Âgé, Titien n’a vu aucun inconvénient à ce qu’on le crut plus vieux qu’il n’était. Pour que l’on rende hommage aux prodiges dont il ne cessait pas d’être capable en dépit de son âge.

Prouver qu’il est Titien

Regarder la peinture de Titien, c’est devoir songer à une lettre de Pietro Aretino – l’Arétin – qui regarde la nuit tomber sur Venise. « Vers certains côtés apparaissait un vert-bleu, vers d’autres un bleu-vert, des tons vraiment composés par un caprice de la nature, maîtresse des maîtres. À l’aide des clairs et des obscurs, elle donnait de la profondeur ou du relief à ce qu’elle voulait faire avancer ou reculer; et moi qui connais votre pinceau comme son inspirateur, je m’exclamai trois ou quatre fois : Ô Titien, où êtes-vous donc ? » Posée en mai 1544, la question reste sans réponse… Ou, plus exactement, les seules réponses qui vaillent sont celles de la légende, de la fable et du mythe. Parce que, grevées de soupçons, elles s’accordent aux silences qui bruissent de sens qui sont ceux de ses toiles.

Les lettres de Titien, celle adressée en 1513 au Conseil des Dix de la Sérénissime République de Venise, celle écrite en 1530 à Frédéric de Gonzague, duc de Mantoue, celle qu’il fait écrire en 1544 par Giovanni della Casa au cardinal Alessandro Farnese, celle encore qu’il adresse en 1545 à Sa Très Sainte Majesté Césarienne, Charles Quint, l’assurance qu’il donne en 1562 à Philippe II : « J’emploierai tout le temps de vie qui me reste pour faire le plus souvent possible à Votre Majesté Catholique la révérence de quelque nouvelle peinture, travaillant pour que mon pinceau lui apporte cette satisfaction que je désire et que mérite la grandeur d’un si haut roi », toutes ces lettres sont celles d’un peintre qui semble n’avoir d’autre ambition que de servir. Maldonne. Titien n’est, n’a jamais été fidèle qu’à Titien. Titien ne sert, n’a servi, que Titien.

Et tous les moyens lui auront été bons. Récit de Vasari : « À ses débuts, quand il commença à peindre dans la manière de Giorgione, à dix-huit ans à peine, fit le portrait d’un gentilhomme de la famille Barbarigo, son ami… on le jugea si bien peint et avec tant d’habileté que, si Titien n’y avait mis son nom dans une ombre, on l’aurait pris pour une œuvre de Giorgione. » Titien ne laisse pas longtemps son nom dans l’ombre… Il n’a voulu qu’on le confonde avec Giorgione, emporté par la peste en 1510, que parce que cette confusion le sert lorsqu’il n’a pas vingt ans encore. Lorsque les « faux » Giorgione qu’il a peints lui ont acquis la renommée qu’il estime devoir lui revenir, il n’a plus d’autre ambition que de prouver qu’il est Titien. Donc incomparable.

Le 5 octobre 1545, Titien lui-même écrit à Charles Quint : « Très Sainte Majesté Césarienne, j’ai remis au Seigneur Don Diego de Mendoza les deux portraits de la Sérénissime Impératrice, pour lesquels j’ai été aussi vigilant que possible. J’aurai voulu les apporter moi-même, mais la longueur du voyage et mon âge ne me le permettent pas. Je prie Votre Majesté de me faire dire les erreurs et les manquements, en me les renvoyant afin que je les corrige ; et que Votre Majesté ne permette pas qu’un autre y touche. » Nouvelle lettre impatiente, le 7 décembre 1545 : « Très Sainte Majesté Césarienne, j’ai envoyé il y a quelques mois à Votre Majesté par les mains du Seigneur Don Diego votre ambassadeur le portrait de la sainte mémoire de l’Impératrice votre épouse, fait de ma main, avec cet autre qui me fut donné par elle comme modèle. J’attends avec un infini dévouement de savoir si mon œuvre Vous est parvenue et si elle Vous a plu ou non. Car si je savais qu’elle vous a plu, je sentirais dans l’âme un contentement que je ne suis pas capable d’exprimer… » On raconte que devant ce portrait peint en 1545 de sa femme Isabelle de Portugal morte le 1er mai 1539, l’empereur pleura. Titien peut ne plus douter de la puissance de sa peinture. Qu’il peigne une impératrice morte ou une déesse, son pouvoir est le même.

« L’art plus puissant que la nature »

En 1554, quelques mois avant qu’une toile dont le Livre X des Métamorphoses d’Ovide a tenu lieu de modèle, quelques mois avant que la toile, récit de l’amour que porte Venus à Adonis, jeune mortel, ne soit expédiée à Madrid, Ludovico Dolce décrit l’œuvre découverte dans l’atelier de Titien : « Je vous jure, Monseigneur, qu’il n’existe pas d’homme perspicace qui ne la prenne pour une femme en chair et en os. Il n’existe pas d’homme assez usé par les ans, ni d’homme aux sens assez endormis, pour ne pas se sentir réchauffé, attendri et ému dans tout son être. » Les toiles de Titien et les Sonnets luxurieux de l’Arétin ont la même raison – érotique – d’être. Mais, à la différence de ces sonnets, les nus de Titien peuvent sembler répondre à l’exigence du Livre du Courtisan de Baldassar Castiglione, livre de chevet de l’empereur Charles Quint, livre qui régit les convenances de toutes les cours : « Pour donc fuir le tourment de cette passion et jouir de la beauté sans passion, il faut que le Courtisan, avec l’aide de la raison, détourne entièrement le désir du corps pour le diriger vers la beauté seule, et, autant qu’il le peut, qu’il la contemple en elle-même, simple et pure, et que dans son imagination il la rende séparée de toute matière, et ainsi fasse d’elle l’amie chérie de son âme. »

Le 10 mai 1533, Charles Quint nomme Titien comte du Palazzo Laterrano, du Consiglio Aulico et du Consistoro. Il lui accorde encore le titre de comte palatin et de chevalier « dello Sperone ». Titien a libre accès à la cour. Enfin l’empereur reconnaît à ses fils, auxquels il concède le titre de « Nobles de l’Empereur », les mêmes privilèges qu’à ceux qui portent un pareil titre depuis quatre générations. La devise que se choisit Titien est NATURA POTENTIOR ARS – l’art est plus puissant que la nature. Elle s’accorde à celle de Charles Quint, « Plus oultre ». Même volonté. Même orgueil.

Apelle, mythe et modèle

Au monastère de San Yuste où il se retire après avoir, rongé par la goutte, abdiqué à Bruxelles, le 28 août 1556, comme aucun empereur ne l’a fait depuis Dioclétien quelque douze siècles plus tôt, Charles Quint emporte plusieurs tableaux de Titien. Titien n’a peut-être pas eu d’autre ambition que d’être l’Apelle de cet empereur. D’Apelle, mort vers 300 avant J.-C., il ne reste rien. Il ne reste qu’un nom que rapportent quelques fragments de textes anciens, il ne reste que quelques anecdotes… Reste un mythe. C’est à ce mythe que Titien s’identifie.

On rapporte qu’Apelle datait des œuvres à l’imparfait. Le légat du pape à Venise commande à Titien un polyptyque. Lorsqu’il l’achève en 1520, il le signe et le date TICIANUS FACIEBAT MDXXII. À l’imparfait. Comme Apelle. Description par Ovide de l’œuvre la plus célèbre d’Apelle : « L’on voit Vénus ruisselante séchant avec ses doigts sa chevelure humide, toute couverte des eaux où elle vient de naître. » En 1520 peut-être, Titien peint une pareille Vénus qui essuie ses cheveux. Comme Apelle.

Pline assure : « Il n’y a de gloire que pour les artistes qui ont peint des tableaux. Il n’y avait aucune peinture à fresque d’Apelle. » Titien ne peint que de rares fresques. Après 1523, il n’en peint plus aucune. Comme Apelle. Alexandre, rapporte encore Pline, « avait interdit par ordonnance qu’aucun autre peintre fit son portrait. »

Charles Quint ne commande plus son portrait qu’à Titien qu’il dit en 1536 être son « Premier peintre ». Titien a auprès de Charles Quint la place qui fut, auprès d’Alexandre, celle d’Apelle. Titien est Apelle. Presque. Un geste de Charles Quint est nécessaire encore. Roger de Piles rapporte en 1708 : « Titien donna tant de jalousie aux courtisans de Charles Quint, qui se plaisait dans la conversation de ce peintre, que cet empereur fut contraint de leur dire qu’il ne manquerait jamais de courtisans, mais qu’il n’aurait pas toujours un Titien. On sait encore que ce peintre ayant un jour laissé tomber un pinceau en faisant le portrait de Charles Quint, cet empereur le ramassa, et que sur le remerciement et l’excuse de Titien lui en faisait, il dit ces paroles : Titien mérite d’être servi par César. » Par ce geste qui fut celui d’Alexandre qui, raconte-t-on, se baissa pour ramasser le pinceau d’Apelle, Charles Quint fait de Titien un nouvel Apelle – comme il se sacre lui-même l’égal d’Alexandre le Grand.

Voir enfin:

How long for France’s accidental president?

Konrad Yakabuski

The Globe and Mail

Jan. 16 2014

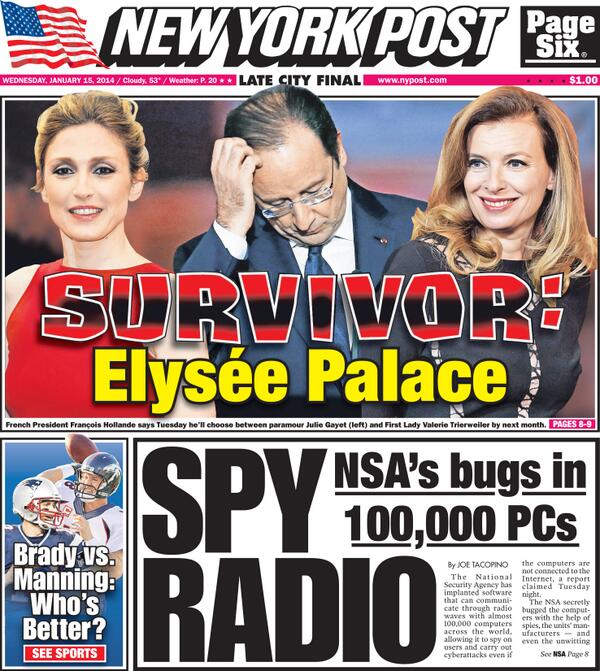

The narrow Paris laneway where French President François Hollande allegedly conducted his trysts, in a rented apartment tied to the Corsican mafia, is called Rue du Cirque – Circus Street, owing to its history as the site of a 19th-century summer carnival. And the no-drama nerd who promised to restore decorum to the presidency after the bling and histrionics of Nicolas Sarkozy has certainly ended up creating a circus worthy of his media-baiting predecessor.

In choosing not to marry his companion when he entered the Élysée Palace, Mr. Hollande was supposed to be making an honest break from the French tradition of presidents who had sexless wives for official functions but sexy mistresses for fun or love. Mr. Hollande was the modern man, finding his soulmate and satisfying protocol in his common-law relationship with journalist Valérie Trierweiler.

Ms. Trierweiler (pronounced Tree-air-vay-lair) became France’s first unmarried first lady, with her own Elysée office, staff, state schedule and web page. Allegations that Mr. Hollande has been having an affair with a younger actress have thrown Ms. Trierweiler’s official status up in the air and left the Socialist Mr. Hollande’s carefully constructed 2014 agenda in tatters. His own ministers see him as a millstone and his ability to govern his fractured nation is in doubt.

To be clear, the French don’t give a flying steak-frites about whom their presidents sleep with. But they do prize elegance. Mr. Sarkozy was an affront to both, with his messy marital breakup, his remarriage to a tipsy model, his new-money friends and his flashy presence. If Mr. Sarkozy’s private life was an open book, it was a cheesy Harlequin the French had no desire to read.

François Mitterrand had elegance. Three decades ago, he could maintain a second family without the media making a fuss or questioning the first-lady status of wife Danielle. Both wife and mistress attended his 1996 burial, which, while noted, was hardly big news.

Mr. Hollande’s mistake was to believe his after-hours dalliances would be treated with similar discretion by the mainstream media. The presidency is no longer held in much reverence by the French. Today, not even Mr. Mitterrand could get away with living a double life, especially if seen to be interfering with his job or contradicting the image he was seeking to project.

But what the French find most galling about Mr. Hollande’s alleged affair, which he has not denied, is his sloppiness. The photos of the helmet-wearing President sneaking out on the back of a scooter, with minimal security detail following him, raise serious questions about whether those protecting this G-7 head of state are plain incompetent or just out to undermine their boss.

Didn’t the Groupe de securité de la présidence de la République, France’s secret service, know of paparazzi snapping photos from a building adjacent to where Mr. Hollande allegedly met actress Julie Gayet? Didn’t it know that the apartment was rented by a Gayet acquaintance whose two previous partners (one of whom was murdered just this year) had possible ties to the Corsican mafia?

This is not just tabloid fodder. Even Le Monde is playing the conspiracy card, asking whether Mr. Sarkozy’s aim of recapturing power had something to do with a gossip magazine’s publication of the compromising photos just four days before Mr. Hollande was set to give a critical speech. “At the Elysée, those loyal to [Mr. Sarkozy] are still in place, particularly in the GSPR,” Le Monde wrote in Monday’s edition.

Mr. Hollande’s Tuesday speech came after a disastrous year economically in France. In pledging tax and spending cuts, Mr. Hollande aimed to make headlines with new pro-business policies and a goal to spread French influence globally. But those ambitions now look laughable, as steamier headlines crowd out Mr. Hollande’s desired narrative.

All this makes the otherwise jovial Mr. Hollande a tragicomic figure. He became president by accident; voters did not so much choose him as reject Mr. Sarkozy. But he has been true to his nickname (Flanby, after a jiggly French custard dessert). In office, he’s had the consistency of Jell-O, with ambiguous policies that please no one in his factionalized party or the broader electorate.

All he had going for him was the appearance of normalcy at home. Now, that’s gone. How long before he is, too?

[…] vérité, longtemps oubliée depuis l’avertissement multimillénaire du dixième commandement mais […]

J’aimeJ’aime

[…] vérité, longtemps oubliée depuis l’avertissement multimillénaire du dixième commandement mais […]

J’aimeJ’aime

[…] vérité, longtemps oubliée depuis l’avertissement multimillénaire du dixième commandement mais […]

J’aimeJ’aime

[…] vérité, longtemps oubliée depuis l’avertissement multimillénaire du dixième commandement mais […]

J’aimeJ’aime

Voir aussi:

Second advert ban in a week for American Apparel after it is censured for sexualising underage girls

Daily Mail

‘Made in Bangladesh’: American Apparel releases controversial new ad starring topless former-Muslim model

Daily Mail

American Apparel

J’aimeJ’aime

INTERNET KILLED THE PLAYBOY STAR

Les mannequins, les célébrités et, oui, les playmates, ne seront pas nues, pour la première fois. La question que tout le monde va probablement nous poser, c’est: pourquoi? (…) Parce que les temps changent.

Hugh Hefner

Hugh Hefner a lancé Playboy pour défendre le libre choix et la liberté sexuelle, explique encore le magazine. Cette bataille a été menée et gagnée. Vous n’êtes qu’à un clic de tous les actes sexuels imaginables, gratuitement. (Publier des photos de nu dans un magazine) est dépassé, désormais. . Il y aura toujours des clichés de femmes dans Playboy, parfois avec des poses «provocantes», mais plus tout à fait nues. (…) Des dizaines de millions d’utilisateurs visitent notre site sans nudité et notre application mobile chaque mois parce qu’il y a, oui, des photos de belles femmes, mais aussi des articles et des vidéos» liées au contenu éditorial du site. Oui, nous prenons un risque en renonçant au nu, mais nous sommes une société qui a le risque dans son ADN.

Scott Flanders (directeur général de Playboy Entreprises)

Le magazine continuera notamment à présenter sa «playmate» du mois, mais elle sera désormais adaptée à un public de 13 ans et plus, a expliqué le responsable du contenu, Cory Jones, dans le quotidien. Depuis son apogée, il y a 40 ans, la diffusion du magazine est passée de 5,6 à 1 million, selon les chiffres de l’Alliance for Audited Media (AAM).

Le groupe Playboy Enterprises est bénéficiaire, selon son directeur général, mais l’édition américaine du magazine papier perd environ trois millions de dollars par an. Elle demeure néanmoins un acteur significatif du marché, à la différence de ses deux rivaux historiques, Penthouse et Hustler, qui ne dépassent pas les 100’000 exemplaires, après avoir fait le choix d’une ligne beaucoup plus explicite et sexuée.

En renonçant au nu intégral, Playboy va dans le sens de l’histoire, déjà suivi par ses nouveaux concurrents papier. Le numéro spécial Swimsuit Issue de l’hebdomadaire Sports Illustrated, qui présente une fois par an des mannequins ou des célébrités en maillots, est souvent présenté comme l’un des magazines les plus rentables au monde. Les Britanniques FHM ou Maxim se sont, plus récemment, positionnés avec succès sur le marché des photos de charme en tenue légère mais pas dénudées.

La révolution avait déjà eu lieu sur le site et l’application mobile de Playboy, débarrassés de toute nudité depuis l’an dernier. Un pari payant puisque le nombre de visites a été multiplié par quatre, passant de 4 à 16 millions d’utilisateurs uniques.

Plus encore que ses concurrents, Playboy fait le pari de la sophistication et du contenu, en capitalisant sur son histoire. Tout au long de son existence, le magazine a largement ouvert ses pages à des écrivains de premier plan comme Vladimir Nabokov, Haruki Murakami ou Margaret Atwood.

Il a aussi publié des entretiens très riches avec des personnalités politiques ou artistiques majeures. Martin Luther King, Malcom X, ou le musicien de jazz Miles Davis y ont dénoncé par exemple les maux dont souffrait l’Amérique des années 60, en proie à la ségrégation et au racisme.

http://www.tdg.ch/culture/Pourquoi-Playboy-renonce-aux-femmes-nues/story/29527562

J’aimeJ’aime

« certaines [jeunes filles] font de la téléréalité pour se vendre plus cher parce qu’elles sont déjà prostituées de base. Les prix augmentent, tu es sollicitée par plus de monde, tu as plus de popularité donc on t’appelle ». Mais les clients y gagnent aussi dans cette affaire car la télé-réalité leur permet de faire leur choix : « Il y a quelqu’un qui va voir une fille à la télé, il va la trouver sexy, il va avoir envie de se la faire et du coup il va demander à la voir », conclut la jeune femme…

http://www.voici.fr/tele-realite/le-temoignage-glacant-dune-candidate-de-telerealite-sur-la-prostitution-dans-le-milieu-639793

J’aimeJ’aime