Une seule faction du monde politique américain a trouvé moyen d’excuser le genre de fanatisme religieux qui nous menace le plus directement ici et maintenant. Et cette faction, je suis désolé et furieux de le dire, est la gauche. Depuis le premier jour de l’immolation du World Trade Center jusqu’en ce moment même, une galerie de pseudo-intellectuels accepte de présenter le plus mauvais visage de l’Islam comme la voix de l’opprimé. Comment ces personnes peuvent-elles supporter de relire leur propre propagande? Les tueurs suicide palestiniens – désavoués et dénoncés par le nouveau chef de l’OLP – qualifiées de victimes du « désespoir. » Les forces d’Al-Qaida et des Taliban présentées comme des porte-paroles dévoyés de l’anti-mondialisation. Les gangsters assoiffés de sang d’Irak, qui préféreraient engloutir toute la population dans la souffrance plutôt que de les laisser voter, joliment décrits comme des « insurgés » ou même, par Michael Moore, comme l’équivalent moral de nos Pères fondateurs. Si c’est ça, le sécularisme libéral, je préfère à tous les coups un modeste et pieux Baptiste amateur de chasse au cerf du Kentucky, aussi longtemps qu’il n’essaie pas de m’imposer ses principes (ce que lui interdit d’ailleurs notre constitution). (…) George Bush est peut-être subjectivement chrétien, mais il a objectivement fait plus pour la laïcité – avec les forces armées américaines – que la totalité de la communauté agnostique américaine combinée et doublée. Christopher Hitchens

Une seule faction du monde politique américain a trouvé moyen d’excuser le genre de fanatisme religieux qui nous menace le plus directement ici et maintenant. Et cette faction, je suis désolé et furieux de le dire, est la gauche. Depuis le premier jour de l’immolation du World Trade Center jusqu’en ce moment même, une galerie de pseudo-intellectuels accepte de présenter le plus mauvais visage de l’Islam comme la voix de l’opprimé. Comment ces personnes peuvent-elles supporter de relire leur propre propagande? Les tueurs suicide palestiniens – désavoués et dénoncés par le nouveau chef de l’OLP – qualifiées de victimes du « désespoir. » Les forces d’Al-Qaida et des Taliban présentées comme des porte-paroles dévoyés de l’anti-mondialisation. Les gangsters assoiffés de sang d’Irak, qui préféreraient engloutir toute la population dans la souffrance plutôt que de les laisser voter, joliment décrits comme des « insurgés » ou même, par Michael Moore, comme l’équivalent moral de nos Pères fondateurs. Si c’est ça, le sécularisme libéral, je préfère à tous les coups un modeste et pieux Baptiste amateur de chasse au cerf du Kentucky, aussi longtemps qu’il n’essaie pas de m’imposer ses principes (ce que lui interdit d’ailleurs notre constitution). (…) George Bush est peut-être subjectivement chrétien, mais il a objectivement fait plus pour la laïcité – avec les forces armées américaines – que la totalité de la communauté agnostique américaine combinée et doublée. Christopher Hitchens

If this is religion, then by all means we should have less of it. But the only people who believe that religion is about believing blindly in a God who blesses and curses on demand and sees science and reason as spawns of Satan are unlettered fundamentalists and their atheistic doppelgangers. Hitchens describes the religious mind as « literal and limited » and the atheistic mind as « ironic and inquiring. » Readers with any sense of irony — and here I do not exclude believers — will be surprised to see how little inquiring Hitchens has done and how limited and literal is his own ill-prepared reduction of religion. (..) Christopher Hitchens is a brilliant man, and there is no living journalist I more enjoy reading. But I have never encountered a book whose author is so fundamentally unacquainted with its subject. In the end, this maddeningly dogmatic book does little more than illustrate one of Hitchens’s pet themes — the ability of dogma to put reason to sleep. Steven Prothero

Imagine a call to ban all scientific inquiry because those who engage in responsible scientific inquiry may be providing the opportunity for fanatics to harness science for their own purposes. Dawkins and his ilk think religious belief of any kind is meaningless, infantile and demeaning so nothing is lost by agitating in the most illiberal way for the suppression of all religion, and not just religious extremism that causes harm to others. (..) Hitchens (…) does see a place for conscience, « whatever it is that makes us behave well when nobody is looking ». For him, « Ordinary conscience will do, without any heavenly wrath behind it ». Frank Brennan

Merci à Christopher Hitchens de nous avoir rappelé à quel point les plus brillants esprits ne sont pas à l’abri du ridicule !

Après Dawkins, voilà donc le héraut de l’Opération Liberté pour l’Irak mais aussi de la dénonciation justifiée des dérives d’un certain catholicisme (notamment la version féminine de l’Abbé Pierre, la Mère Térésa, dans « La Position de la missionnaire ») à se fourvoyer dans le énième retour de la mode de l’anti-christianisme.

Avec, comme le rappellent deux de ses fans, le chef du département de Religion de Boston University Stephen Prothero et le Jésuite australien Frank Brennan, la même touchante obstination à répéter les erreurs séculaires de ses prédécesseurs.

D’abord, on se plombe avec des titres impossibles de subtilité: « La racine de tout mal? » pour le documentaire de Dawkins et « Comment la religion empoisonne tout » pour le sous-titre du bouquin de Hitchens.

Puis, on s’enferre avec la plus infantile possible définition de ladite religion appuyée par la liste de toutes les vilainies qu’on peut trouver à son sujet.

Avant de s’enfoncer un peu plus avec la dénonciation de textes qu’on a non seulement pas compris mais probablement pas lus.

Pour révéler enfin à la face du monde des horreurs que ladite religion a déjà critiquées d’elle-même depuis quelques siècles, voire millénaires!

Au risque quand même de jeter un petit doute sur ses précédentes dénonciations d’autres mouvements religieux réellement aberrants et dangereux comme un certain islam …

The Unbeliever

Hitchens argues that religion is man-made and murderous.

Reviewed by Stephen Prothero

The Washington post

May 6, 2007

GOD IS NOT GREAT

How Religion Poisons Everything

By Christopher Hitchens

Twelve. 307 pp. $24.99

A century and a half ago Pope Pius IX published the Syllabus of Errors, a rhetorical tour de force against the high crimes and misdemeanors of the modern world. God Is Not Great, by the British journalist and professional provocateur Christopher Hitchens, is the atheists’ equivalent: an unrelenting enumeration of religion’s sins and wickedness, written with much of the rhetorical pomp and all of the imperial condescension of a Vatican encyclical.

Hitchens, who once described Mother Teresa as « a fanatic, a fundamentalist, and a fraud, » is notorious for making mincemeat out of sacred cows, but in this book it is the sacred itself that is skewered. Religion, Hitchens writes, is « violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism and tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children. » Channeling the anti-supernatural spirits of other acolytes of the « new atheism, » Hitchens argues that religion is « man-made » and murderous, originating in fear and sustained by brute force. Like Richard Dawkins, he denounces the religious education of young people as child abuse. Like Sam Harris, he fires away at the Koran as well as the Bible. And like Daniel Dennett, he views faith as wish-fulfillment.

Historian George Marsden once described fundamentalism as evangelicalism that is mad about something. If so, these evangelistic atheists have something in common with their fundamentalist foes, and Hitchens is the maddest of the lot. Protestant theologian John Calvin was « a sadist and torturer and killer, » Hitchens writes, and the Bible « contain[s] a warrant for trafficking in humans, for ethnic cleansing, for slavery, for bride-price, and for indiscriminate massacre. »

As should be obvious to any reasonable person — unlike Hitchens I do not exclude believers from this category — horrors and good deeds are performed by believers and non-believers alike. But in Hitchens’s Manichaean world, religion does little good and secularism hardly any evil. Indeed, Hitchens arrives at the conclusion that the secular murderousness of Stalin’s purges wasn’t really secular at all, since, as he quotes George Orwell, « a totalitarian state is in effect a theocracy. » And in North Korea today, what has gone awry is not communism but Confucianism.

Hitchens is not so forgiving when it comes to religion’s transgressions. He aims his poison pen at the Dalai Lama, St. Francis and Gandhi. Among religious leaders only the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. comes off well. But in the gospel according to Hitchens whatever good King did accrues to his humanism rather than his Christianity. In fact, King was not actually a Christian at all, argues Hitchens, since he rejected the sadism that characterizes the teachings of Jesus. « No supernatural force was required to make the case against racism » in postwar America, writes Hitchens. But he’s wrong. It was the prophetic faith of black believers that gave them the strength to stand up to the indignities of fire hoses and police dogs. As for those white liberals inspired by Paine, Mencken and Hitchens’s other secular heroes, well, they stood down.

Hitchens says a lot of true things in this wrongheaded book. He is right that you can be moral without being religious. He is right to track contemporary sexism and sexual repression to ancient religious beliefs. And his attack on « intelligent design » is not only convincing but comical, coursing as it does through the crude architecture of the appendix and our inconvenient « urinogenital arrangements. »

What Hitchens gets wrong is religion itself.

Hitchens claims that some of his best friends are believers. If so, he doesn’t know much about his best friends. He writes about religious people the way northern racists used to talk about « Negroes » — with feigned knowing and a sneer. God Is Not Great assumes a childish definition of religion and then criticizes religious people for believing such foolery. But it is Hitchens who is the naïf. To read this oddly innocent book as gospel is to believe that ordinary Catholics are proud of the Inquisition, that ordinary Hindus view masturbation as an offense against Krishna, and that ordinary Jews cheer when a renegade Orthodox rebbe sucks the blood off a freshly circumcised penis. It is to believe that faith is always blind and rituals always empty — that there is no difference between taking communion and drinking the Kool-Aid (a beverage Hitchens feels compelled to mention no fewer than three times).

If this is religion, then by all means we should have less of it. But the only people who believe that religion is about believing blindly in a God who blesses and curses on demand and sees science and reason as spawns of Satan are unlettered fundamentalists and their atheistic doppelgangers. Hitchens describes the religious mind as « literal and limited » and the atheistic mind as « ironic and inquiring. » Readers with any sense of irony — and here I do not exclude believers — will be surprised to see how little inquiring Hitchens has done and how limited and literal is his own ill-prepared reduction of religion.

Christopher Hitchens is a brilliant man, and there is no living journalist I more enjoy reading. But I have never encountered a book whose author is so fundamentally unacquainted with its subject. In the end, this maddeningly dogmatic book does little more than illustrate one of Hitchens’s pet themes — the ability of dogma to put reason to sleep. ·

Stephen Prothero is the chair of Boston University’s religion department and the author of « Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know — and Doesn’t. »

Voir aussi:

The atheist manifesto

There can be no peace unless believers and atheists share an equal place in the public square of a free and democratic society, argues Frank Brennan

The Australian

June 02, 2007

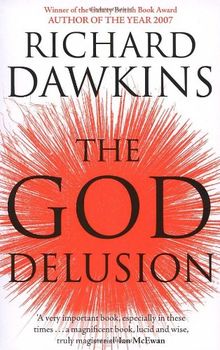

BEFORE the publication of Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion, I had presumed that in Western intellectual circles the atheists were ahead on points and that they were little troubled by the doings of those they regarded as well meaning, slightly befuddled religious people. Like them, I had strong concerns about fundamentalists who used their simplistic religious beliefs to buttress their commitment to violent or undemocratic action.

I now realise that Dawkins and his ilk are upset even by religious people such as me, perhaps especially by religious people such as me. Dawkins claims that moderation in faith fosters fanaticism: « Even mild and moderate religion helps to provide the climate of faith in which extremism naturally flourishes. »

Dawkins’s « take home message » is that we should blame « religion itself, not religious extremism, as though that were some kind of perversion of real, decent religion ».

The same argument would not be made for scientific inquiry. Imagine a call to ban all scientific inquiry because those who engage in responsible scientific inquiry may be providing the opportunity for fanatics to harness science for their own purposes. Dawkins and his ilk think religious belief of any kind is meaningless, infantile and demeaning so nothing is lost by agitating in the most illiberal way for the suppression of all religion, and not just religious extremism that causes harm to others.

The successful marketing of The God Delusion has unleashed a steady flow of anti-religious rantings from intelligent authors who have thrown respect for the other and careful argument to the wind. Instead of proposing strategies for weeding out religious fundamentalists who pose a threat to the freedom, dignity and rights of others, these authors are proposing a scorched-earth policy of killing off all religion.

Christopher Hitchens has visited most of the trouble spots of the world. He is an acute journalistic critic of warring parties in any dispute. But in God is Not Great he is not the bystander adjudicating between the fundamentalist Muslim suicide bombers and the conservative Christian backers of the Bush White House. He is a belligerent, unyielding disputant asserting that religion ought to have no place at the table of public deliberation.

While he, who is not Irish, thinks Mother Teresa had no right to express her opinion about divorce law reform in Ireland, he has no hesitation in telling Australians about what we should be doing in Iraq. Why not the same rule for political intervention by outsiders, whether or not they are religious?

In the wake of death threats for having offered shelter to his friend Salman Rushdie, he concludes with one of his many universal judgments against all religions and religious persons: « The true believer cannot rest until the whole world bows the knee. Is it not obvious to all, say the pious, that religious authority is paramount, and that those who decline to recognise it have forfeited their right to exist? » It is not obvious to me.

Hitchens has dedicated his book to British novelist Ian McEwan, « whose body of fiction shows an extraordinary ability to elucidate the numinous without conceding anything to the supernatural ». Hitchens had never been religious, but in his Marxist phase he admired Trotsky, who had a sense « of the unquenchable yearning of the poor and oppressed to rise above the strictly material world and to achieve something transcendent ».

Now he sees no need for transcendence beyond the strictly material world; he is content with an elucidation of the numinous in the written word as from the pen of McEwan.

He does concede that « religious faith is ineradicable. It will never die out, or at least not until we get over our fear of death, and of the dark, and of the unknown, and of each other. » He does see a place for conscience, « whatever it is that makes us behave well when nobody is looking ». For him, « Ordinary conscience will do, without any heavenly wrath behind it. »

Some of us do find that we can form and inform our conscience even better when we believe that a loving God is accompanying us in the lonely chambers of decision. Some of us stand tallest when we submit and surrender to death, darkness and the other with dignity, and love, with a religious sensibility.

Michel Onfray’s The Atheist Manifesto is one of those books you can judge by its back cover. It depicts the French author against a blank wall with a vacuum cleaner at his feet. His book is the result of a flurried, philosophical spring-clean of history. He has swept up a potpourri of anti-religious content through the centuries and prefaced each collection of detritus with sweeping assertions such as: « monotheism loathes intelligence »; « in science, the church has always been wrong about everything: faced with epistemological truth it automatically persecutes the discoverer »; « monotheisms have no love for intelligence, books, knowledge, science ». The Catholic Church « excels in the destruction of civilisations. It invented ethnocide »; and « monotheism is fatally fixated on death ».

The argument for the last assertion is supported by the outrageous claim that John Paul II « actively defend(ed) the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Tutsi by the Catholic Hutu of Rwanda ». There is no evidence for such a claim. Consider the former pope’s address to the African bishops a few days after the killings began: « I feel the need to launch an appeal to stop that homicide of violence. Together with you, I raise my voice to tell all of you: stop these acts of violence! Stop these tragedies! Stop these fratricidal massacres! » Onfray begins the book with the stylistic flourish of a series of « mystical postcards » and assures the reader, « In none of those places did I feel superior to those who believed in spirits, in the immortal soul, in the breath of the gods, the presence of angels, the power of prayer, the effectiveness of ritual, the validity of incantations, communion with voodoo spirits, haemoglobin-based miracles, the Virgin’s tears, the resurrection of a crucified man. Never. » By the book’s end, the reader realises that the answer was not « never » but « always ». Onfray writes with a haughty and dismissive arrogance towards any person who has a religious sentiment.

He even denies equality of treatment in the public square to any religious believer.

« Equality between the believing Jew and the philosopher who proceeds according to the hypothetico-deductive model? Equality between the believer and the thinker who deconstructs the manufacture of belief, the building of a myth, the creation of a fable? Equality between the Muslim and the scrupulous analyst? If we say yes to these questions, then let’s stop thinking. »

What are we to do, start fighting? Do we not need to accord equality to all these people in the public square of a free and democratic society, applying the same rules to each of them whether or not they are religious? And is this not the real challenge for us in this post-September 11 world?

Tamas Pataki has contributed an Australian home-grown polemic, Against Religion. He is less shrill and more measured than the French and English pamphleteers, and adds local colour with attacks on Peter Costello, whose « appearances at Hillsong received an unusual degree of attention from the Australian media ». The « mendacious John Howard » joins company with « the apocalyptic Tony Blair ».

He argues that religion captures the mind when reinforced and held in place by unconscious needs and fantasies. According to Pataki, religious people are narcissistic individuals who want to be loved and to feel special. They find it difficult to accept that « there is nothing higher than earthly human love because the love of ordinary men and women is so fragile and incestuously tainted for them. So they must seek something ‘higher’, something transcendent. »

All three authors find it inconceivable that a religious person can accord reason and science their due place, can live a balanced life without being sexually repressed and can welcome the insights of Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud and Bertrand Russell. Hitchens asserts, « Thanks to the telescope and microscope, (religion) no longer offers an explanation of anything important. It can now only impede or retard. » Regardless of the knowledge provided us by the telescope and microscope, every person, generation and culture has to make existential sense of the abyss that will always lie beyond the reach of the telescope and the microscope.

The thinking, self-critical religious person parts company with these three authors at the edge of what can be known about the self and about the world. For these authors, there is nothing beyond that edge because it is not knowable. US liberal Ronald Dworkin has recently set down the only realistic choice for the modern nation-state: « A religious nation that tolerates non-belief? Or a secular nation that tolerates religion? »

In our globalised world, there will always be a Mother Teresa or a Hitchens wanting to make their contribution to public debate about law and policy even in those countries where they do not enjoy citizenship. We need rules of engagement that apply equally to people of religious faith and those with none. We need to distinguish the role of the individual citizen and the role of the person in a position of public trust. That public trust must be discharged faithfully whether or not the office holder is a religious person.

Religious beliefs and philosophical standpoints may well help to inform the discharge of that public trust. It is too simplistic to assert that engagement in the public square or in a position of public trust ought to be open only to those who have no religious beliefs or who leave their religious commitments at home.

Public intellectuals such as these three authors may relish the public expression of scorn and disdain for all religions. But they do nothing to assist the needed public discernment of the limits on personal opinions and preferences in the public square, and in law and public policy. Sadly, these three intelligent, gifted and illiberal authors have demonstrated that it is not only Islamic fundamentalists who fail to understand the rules for civil discourse and engagement in the post-September 11 public square.

Frank Brennan is a Jesuit priest. His latest book is Acting on Conscience. He appeared at the Sydney Writers Festival with Tamas Pataki and Michel Onfray yesterday.