On April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his assassination, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the lectern at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. The United States had been in active combat in Vietnam for two years and tens of thousands of people had been killed, including some 10,000 American troops. The political establishment — from left to right — backed the war, and more than 400,000 American service members were in Vietnam, their lives on the line. Many of King’s strongest allies urged him to remain silent about the war or at least to soft-pedal any criticism. They knew that if he told the whole truth about the unjust and disastrous war he would be falsely labeled a Communist, suffer retaliation and severe backlash, alienate supporters and threaten the fragile progress of the civil rights movement. King rejected all the well-meaning advice and said, “I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice.” Quoting a statement by the Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, he said, “A time comes when silence is betrayal” and added, “that time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.” It was a lonely, moral stance. And it cost him. But it set an example of what is required of us if we are to honor our deepest values in times of crisis, even when silence would better serve our personal interests or the communities and causes we hold most dear. It’s what I think about when I go over the excuses and rationalizations that have kept me largely silent on one of the great moral challenges of our time: the crisis in Israel-Palestine. I have not been alone. Until very recently, the entire Congress has remained mostly silent on the human rights nightmare that has unfolded in the occupied territories. Our elected representatives, who operate in a political environment where Israel’s political lobby holds well-documented power, have consistently minimized and deflected criticism of the State of Israel, even as it has grown more emboldened in its occupation of Palestinian territory and adopted some practices reminiscent of apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow segregation in the United States. Many civil rights activists and organizations have remained silent as well, not because they lack concern or sympathy for the Palestinian people, but because they fear loss of funding from foundations, and false charges of anti-Semitism. They worry, as I once did, that their important social justice work will be compromised or discredited by smear campaigns. Similarly, many students are fearful of expressing support for Palestinian rights because of the McCarthyite tactics of secret organizations like Canary Mission, which blacklists those who publicly dare to support boycotts against Israel, jeopardizing their employment prospects and future careers. Reading King’s speech at Riverside more than 50 years later, I am left with little doubt that his teachings and message require us to speak out passionately against the human rights crisis in Israel-Palestine, despite the risks and despite the complexity of the issues. King argued, when speaking of Vietnam, that even “when the issues at hand seem as perplexing as they often do in the case of this dreadful conflict,” we must not be mesmerized by uncertainty. “We must speak with all the humility that is appropriate to our limited vision, but we must speak.” And so, if we are to honor King’s message and not merely the man, we must condemn Israel’s actions: unrelenting violations of international law, continued occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, home demolitions and land confiscations. We must cry out at the treatment of Palestinians at checkpoints, the routine searches of their homes and restrictions on their movements, and the severely limited access to decent housing, schools, food, hospitals and water that many of them face. We must not tolerate Israel’s refusal even to discuss the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, as prescribed by United Nations resolutions, and we ought to question the U.S. government funds that have supported multiple hostilities and thousands of civilian casualties in Gaza, as well as the $38 billion the U.S. government has pledged in military support to Israel. And finally, we must, with as much courage and conviction as we can muster, speak out against the system of legal discrimination that exists inside Israel, a system complete with, according to Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, more than 50 laws that discriminate against Palestinians — such as the new nation-state law that says explicitly that only Jewish Israelis have the right of self-determination in Israel, ignoring the rights of the Arab minority that makes up 21 percent of the population. Of course, there will be those who say that we can’t know for sure what King would do or think regarding Israel-Palestine today. That is true. The evidence regarding King’s views on Israel is complicated and contradictory. Although the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee denounced Israel’s actions against Palestinians, King found himself conflicted. Like many black leaders of the time, he recognized European Jewry as a persecuted, oppressed and homeless people striving to build a nation of their own, and he wanted to show solidarity with the Jewish community, which had been a critically important ally in the civil rights movement. Ultimately, King canceled a pilgrimage to Israel in 1967 after Israel captured the West Bank. During a phone call about the visit with his advisers, he said, “I just think that if I go, the Arab world, and of course Africa and Asia for that matter, would interpret this as endorsing everything that Israel has done, and I do have questions of doubt.” He continued to support Israel’s right to exist but also said on national television that it would be necessary for Israel to return parts of its conquered territory to achieve true peace and security and to avoid exacerbating the conflict. There was no way King could publicly reconcile his commitment to nonviolence and justice for all people, everywhere, with what had transpired after the 1967 war. Today, we can only speculate about where King would stand. Yet I find myself in agreement with the historian Robin D.G. Kelley, who concluded that, if King had the opportunity to study the current situation in the same way he had studied Vietnam, “his unequivocal opposition to violence, colonialism, racism and militarism would have made him an incisive critic of Israel’s current policies.” Indeed, King’s views may have evolved alongside many other spiritually grounded thinkers, like Rabbi Brian Walt, who has spoken publicly about the reasons that he abandoned his faith in what he viewed as political Zionism. (…) During more than 20 visits to the West Bank and Gaza, he saw horrific human rights abuses, including Palestinian homes being bulldozed while people cried — children’s toys strewn over one demolished site — and saw Palestinian lands being confiscated to make way for new illegal settlements subsidized by the Israeli government. He was forced to reckon with the reality that these demolitions, settlements and acts of violent dispossession were not rogue moves, but fully supported and enabled by the Israeli military. For him, the turning point was witnessing legalized discrimination against Palestinians — including streets for Jews only — which, he said, was worse in some ways than what he had witnessed as a boy in South Africa. (…) Jewish Voice for Peace, for example, aims to educate the American public about “the forced displacement of approximately 750,000 Palestinians that began with Israel’s establishment and that continues to this day.” (…) In view of these developments, it seems the days when critiques of Zionism and the actions of the State of Israel can be written off as anti-Semitism are coming to an end. There seems to be increased understanding that criticism of the policies and practices of the Israeli government is not, in itself, anti-Semitic. (…) the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II (…) declared in a riveting speech last year that we cannot talk about justice without addressing the displacement of native peoples, the systemic racism of colonialism and the injustice of government repression. In the same breath he said: “I want to say, as clearly as I know how, that the humanity and the dignity of any person or people cannot in any way diminish the humanity and dignity of another person or another people. To hold fast to the image of God in every person is to insist that the Palestinian child is as precious as the Jewish child.” Guided by this kind of moral clarity, faith groups are taking action. In 2016, the pension board of the United Methodist Church excluded from its multibillion-dollar pension fund Israeli banks whose loans for settlement construction violate international law. Similarly, the United Church of Christ the year before passed a resolution calling for divestments and boycotts of companies that profit from Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories. Even in Congress, change is on the horizon. For the first time, two sitting members, Representatives Ilhan Omar, Democrat of Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, Democrat of Michigan, publicly support the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. In 2017, Representative Betty McCollum, Democrat of Minnesota, introduced a resolution to ensure that no U.S. military aid went to support Israel’s juvenile military detention system. Israel regularly prosecutes Palestinian children detainees in the occupied territories in military court. None of this is to say that the tide has turned entirely or that retaliation has ceased against those who express strong support for Palestinian rights. To the contrary, just as King received fierce, overwhelming criticism for his speech condemning the Vietnam War — 168 major newspapers, including The Times, denounced the address the following day — those who speak publicly in support of the liberation of the Palestinian people still risk condemnation and backlash. Bahia Amawi, an American speech pathologist of Palestinian descent, was recently terminated for refusing to sign a contract that contains an anti-boycott pledge stating that she does not, and will not, participate in boycotting the State of Israel. In November, Marc Lamont Hill was fired from CNN for giving a speech in support of Palestinian rights that was grossly misinterpreted as expressing support for violence. Canary Mission continues to pose a serious threat to student activists. And just over a week ago, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama, apparently under pressure mainly from segments of the Jewish community and others, rescinded an honor it bestowed upon the civil rights icon Angela Davis, who has been a vocal critic of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and supports B.D.S. But that attack backfired. Within 48 hours, academics and activists had mobilized in response. The mayor of Birmingham, Randall Woodfin, as well as the Birmingham School Board and the City Council, expressed outrage at the institute’s decision. The council unanimously passed a resolution in Davis’ honor, and an alternative event is being organized to celebrate her decades-long commitment to liberation for all. I cannot say for certain that King would applaud Birmingham for its zealous defense of Angela Davis’s solidarity with Palestinian people. But I do. In this new year, I aim to speak with greater courage and conviction about injustices beyond our borders, particularly those that are funded by our government, and stand in solidarity with struggles for democracy and freedom. My conscience leaves me no other choice. Michelle Alexander

On April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his assassination, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the lectern at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. The United States had been in active combat in Vietnam for two years and tens of thousands of people had been killed, including some 10,000 American troops. The political establishment — from left to right — backed the war, and more than 400,000 American service members were in Vietnam, their lives on the line. Many of King’s strongest allies urged him to remain silent about the war or at least to soft-pedal any criticism. They knew that if he told the whole truth about the unjust and disastrous war he would be falsely labeled a Communist, suffer retaliation and severe backlash, alienate supporters and threaten the fragile progress of the civil rights movement. King rejected all the well-meaning advice and said, “I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice.” Quoting a statement by the Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, he said, “A time comes when silence is betrayal” and added, “that time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.” It was a lonely, moral stance. And it cost him. But it set an example of what is required of us if we are to honor our deepest values in times of crisis, even when silence would better serve our personal interests or the communities and causes we hold most dear. It’s what I think about when I go over the excuses and rationalizations that have kept me largely silent on one of the great moral challenges of our time: the crisis in Israel-Palestine. I have not been alone. Until very recently, the entire Congress has remained mostly silent on the human rights nightmare that has unfolded in the occupied territories. Our elected representatives, who operate in a political environment where Israel’s political lobby holds well-documented power, have consistently minimized and deflected criticism of the State of Israel, even as it has grown more emboldened in its occupation of Palestinian territory and adopted some practices reminiscent of apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow segregation in the United States. Many civil rights activists and organizations have remained silent as well, not because they lack concern or sympathy for the Palestinian people, but because they fear loss of funding from foundations, and false charges of anti-Semitism. They worry, as I once did, that their important social justice work will be compromised or discredited by smear campaigns. Similarly, many students are fearful of expressing support for Palestinian rights because of the McCarthyite tactics of secret organizations like Canary Mission, which blacklists those who publicly dare to support boycotts against Israel, jeopardizing their employment prospects and future careers. Reading King’s speech at Riverside more than 50 years later, I am left with little doubt that his teachings and message require us to speak out passionately against the human rights crisis in Israel-Palestine, despite the risks and despite the complexity of the issues. King argued, when speaking of Vietnam, that even “when the issues at hand seem as perplexing as they often do in the case of this dreadful conflict,” we must not be mesmerized by uncertainty. “We must speak with all the humility that is appropriate to our limited vision, but we must speak.” And so, if we are to honor King’s message and not merely the man, we must condemn Israel’s actions: unrelenting violations of international law, continued occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, home demolitions and land confiscations. We must cry out at the treatment of Palestinians at checkpoints, the routine searches of their homes and restrictions on their movements, and the severely limited access to decent housing, schools, food, hospitals and water that many of them face. We must not tolerate Israel’s refusal even to discuss the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, as prescribed by United Nations resolutions, and we ought to question the U.S. government funds that have supported multiple hostilities and thousands of civilian casualties in Gaza, as well as the $38 billion the U.S. government has pledged in military support to Israel. And finally, we must, with as much courage and conviction as we can muster, speak out against the system of legal discrimination that exists inside Israel, a system complete with, according to Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, more than 50 laws that discriminate against Palestinians — such as the new nation-state law that says explicitly that only Jewish Israelis have the right of self-determination in Israel, ignoring the rights of the Arab minority that makes up 21 percent of the population. Of course, there will be those who say that we can’t know for sure what King would do or think regarding Israel-Palestine today. That is true. The evidence regarding King’s views on Israel is complicated and contradictory. Although the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee denounced Israel’s actions against Palestinians, King found himself conflicted. Like many black leaders of the time, he recognized European Jewry as a persecuted, oppressed and homeless people striving to build a nation of their own, and he wanted to show solidarity with the Jewish community, which had been a critically important ally in the civil rights movement. Ultimately, King canceled a pilgrimage to Israel in 1967 after Israel captured the West Bank. During a phone call about the visit with his advisers, he said, “I just think that if I go, the Arab world, and of course Africa and Asia for that matter, would interpret this as endorsing everything that Israel has done, and I do have questions of doubt.” He continued to support Israel’s right to exist but also said on national television that it would be necessary for Israel to return parts of its conquered territory to achieve true peace and security and to avoid exacerbating the conflict. There was no way King could publicly reconcile his commitment to nonviolence and justice for all people, everywhere, with what had transpired after the 1967 war. Today, we can only speculate about where King would stand. Yet I find myself in agreement with the historian Robin D.G. Kelley, who concluded that, if King had the opportunity to study the current situation in the same way he had studied Vietnam, “his unequivocal opposition to violence, colonialism, racism and militarism would have made him an incisive critic of Israel’s current policies.” Indeed, King’s views may have evolved alongside many other spiritually grounded thinkers, like Rabbi Brian Walt, who has spoken publicly about the reasons that he abandoned his faith in what he viewed as political Zionism. (…) During more than 20 visits to the West Bank and Gaza, he saw horrific human rights abuses, including Palestinian homes being bulldozed while people cried — children’s toys strewn over one demolished site — and saw Palestinian lands being confiscated to make way for new illegal settlements subsidized by the Israeli government. He was forced to reckon with the reality that these demolitions, settlements and acts of violent dispossession were not rogue moves, but fully supported and enabled by the Israeli military. For him, the turning point was witnessing legalized discrimination against Palestinians — including streets for Jews only — which, he said, was worse in some ways than what he had witnessed as a boy in South Africa. (…) Jewish Voice for Peace, for example, aims to educate the American public about “the forced displacement of approximately 750,000 Palestinians that began with Israel’s establishment and that continues to this day.” (…) In view of these developments, it seems the days when critiques of Zionism and the actions of the State of Israel can be written off as anti-Semitism are coming to an end. There seems to be increased understanding that criticism of the policies and practices of the Israeli government is not, in itself, anti-Semitic. (…) the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II (…) declared in a riveting speech last year that we cannot talk about justice without addressing the displacement of native peoples, the systemic racism of colonialism and the injustice of government repression. In the same breath he said: “I want to say, as clearly as I know how, that the humanity and the dignity of any person or people cannot in any way diminish the humanity and dignity of another person or another people. To hold fast to the image of God in every person is to insist that the Palestinian child is as precious as the Jewish child.” Guided by this kind of moral clarity, faith groups are taking action. In 2016, the pension board of the United Methodist Church excluded from its multibillion-dollar pension fund Israeli banks whose loans for settlement construction violate international law. Similarly, the United Church of Christ the year before passed a resolution calling for divestments and boycotts of companies that profit from Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories. Even in Congress, change is on the horizon. For the first time, two sitting members, Representatives Ilhan Omar, Democrat of Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, Democrat of Michigan, publicly support the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. In 2017, Representative Betty McCollum, Democrat of Minnesota, introduced a resolution to ensure that no U.S. military aid went to support Israel’s juvenile military detention system. Israel regularly prosecutes Palestinian children detainees in the occupied territories in military court. None of this is to say that the tide has turned entirely or that retaliation has ceased against those who express strong support for Palestinian rights. To the contrary, just as King received fierce, overwhelming criticism for his speech condemning the Vietnam War — 168 major newspapers, including The Times, denounced the address the following day — those who speak publicly in support of the liberation of the Palestinian people still risk condemnation and backlash. Bahia Amawi, an American speech pathologist of Palestinian descent, was recently terminated for refusing to sign a contract that contains an anti-boycott pledge stating that she does not, and will not, participate in boycotting the State of Israel. In November, Marc Lamont Hill was fired from CNN for giving a speech in support of Palestinian rights that was grossly misinterpreted as expressing support for violence. Canary Mission continues to pose a serious threat to student activists. And just over a week ago, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama, apparently under pressure mainly from segments of the Jewish community and others, rescinded an honor it bestowed upon the civil rights icon Angela Davis, who has been a vocal critic of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and supports B.D.S. But that attack backfired. Within 48 hours, academics and activists had mobilized in response. The mayor of Birmingham, Randall Woodfin, as well as the Birmingham School Board and the City Council, expressed outrage at the institute’s decision. The council unanimously passed a resolution in Davis’ honor, and an alternative event is being organized to celebrate her decades-long commitment to liberation for all. I cannot say for certain that King would applaud Birmingham for its zealous defense of Angela Davis’s solidarity with Palestinian people. But I do. In this new year, I aim to speak with greater courage and conviction about injustices beyond our borders, particularly those that are funded by our government, and stand in solidarity with struggles for democracy and freedom. My conscience leaves me no other choice. Michelle Alexander

“I think it’s a trope that has certainly been seen in Hollywood films for decades. Think about the white teacher in the inner city school. The Michelle Pfeiffer one [in Dangerous Minds]. The Principal. Music of the Heart, where Meryl Streep was a music teacher. Wildcats. I think these stories probably read well in a pitch meeting: ‘Goldie Hawn coaching an inner city football team.’“They make it look like Japan would not have made it out of the feudal period without Tom Cruise.” And the west wouldn’t have been tamed and we’d have no civilization if Kevin Costner didn’t ride into town. Laurence Lerman

Belle becomes empowered to challenge the white characters that view themselves as her savior on their veiled racism, which marks a welcome departure from one of Hollywood’s most enduring cinematic tropes: the white savior. When it comes to race-relations dramas—and slavery narratives, in particular—the white savior has become one of Hollywood’s most reliably offensive clichés. The black servants of The Help needed a perky, progressive Emma Stone to shed light on their plight; the football bruiser in The Blind Side couldn’t have done it without fiery Sandra Bullock; the black athletes in Cool Runnings and The Air Up There needed the guidance of their white coach; and in 12 Years A Slave, Solomon Northup, played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, is liberated at the eleventh hour by a Jesus-looking Brad Pitt (in a classic Deus Ex Machina). The issue, according to Lerman, is more complex given the nature of Hollywood and the various power structures at play. While there are plenty of important stories to tell featuring people of color, there are only a small number of people of color in Hollywood with the clout to get a film green-lit—especially since we’re living in an age where international box office trumps domestic. This troubling disparity often results in a white star needing to be featured in a film with a predominantly minority cast to secure the necessary financing—as was the case with Pitt’s appearance in 12 Years A Slave, a film produced by his company, Plan B. And who can forget the controversy over the outrageous Italian movie posters for 12 Years A Slave, which prominently featured the film’s white movie stars—Pitt and Michael Fassbender—in favor of the movie’s real star, Chiwetel Ejiofor. Without ruining the film for you, part of what makes Belle so refreshing is that its portrayal of black characters, namely Belle, is one of dignity. They aren’t the typical uneducated blacks you see in films that need to be shown the light by a white knight, for they’re blessed with more intellect and class than many of their white subjugators, who soon come to realize that Belle, through her grace and wisdom, is their savior. “Her family thought they were giving her great love, but until she’s able to take that freedom for herself and find self-love and feel comfortable in her own skin, that’s when she’s ready to challenge them,” says Mbatha-Raw. “It just felt like a story that needed to be told.” The Daily Beast

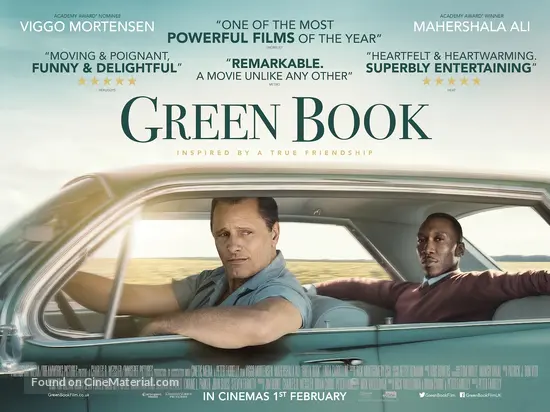

“Driving Miss Daisy” (…) “The Upside” (…) “Green Book” (…) symbolize a style of American storytelling in which the wheels of interracial friendship are greased by employment, in which prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of his white, frequently racist counterpart. All the optimism of racial progress — from desegregation to integration to equality to something like true companionship — is stipulated by terms of service. Thirty years separate “Driving Miss Daisy” from these two new films, but how much time has passed, really? The bond in all three is conditionally transactional, possible only if it’s mediated by money. “The Upside” has the rich, quadriplegic author Phillip Lacasse (Cranston) hire an ex-con named Dell Scott (Hart) to be his “life auxiliary.” “Green Book” reverses the races so that some white muscle (Mortensen) drives the black pianist Don Shirley (Ali) to gigs throughout the Deep South in the 1960s. It’s “The Upside Down.” These pay-for-playmate transactions are a modern pastime, different from an entire history of popular culture that simply required black actors to serve white stars without even the illusion of friendship. It was really only possible in a post-integration America, possible after Sidney Poitier made black stardom loosely feasible for the white studios, possible after the moral and legal adjustments won during the civil rights movements, possible after the political recriminations of the black power and blaxploitation eras let black people regularly frolic among themselves for the first time since the invention of the Hollywood movie. Possible, basically, only in the 1980s, after the movements had more or less subsided and capitalism and jokey white paternalism ran wild. On television in this era, rich white sitcom families vacuumed up little black boys, on “Diff’rent Strokes,” on “Webster.” On “Diff’rent Strokes,” the adopted boys are the orphaned Harlem sons of Phillip Drummond’s maid. Not only was money supposed to lubricate racial integration; it was perhaps supposed to mitigate a history of keeping black people apart and oppressed. (…) The sitcoms weren’t officially social experiments, but they were light advertisements for the civilizing (and alienating) benefits of white wealth on black life. (…) Any time a white person comes anywhere close to the rescue of a black person the academy is primed to say, “Good for you!,” whether it’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Mississippi Burning,” “The Blind Side,” or “The Help.” The year “Driving Miss Daisy” won those Oscars, Morgan Freeman also had a supporting role in a drama (“Glory”) that placed a white Union colonel at its center and was very much in the mix that night. (…) And Spike Lee lost the original screenplay award for “Do the Right Thing,” his masterpiece about a boiled-over pot of racial animus in Brooklyn. (…) Lee’s movie dramatized a starker truth — we couldn’t all just get along. For what it’s worth, Lee is now up for more Oscars. His film “BlacKkKlansman” has six nominations. Given the five for “Green Book,” basically so is “Driving Miss Daisy.” Which is to say that 2019 might just be 1990 all over again. (…) One headache with these movies, even one as well done as “Driving Miss Daisy,” is that they romanticize their workplaces and treat their black characters as the ideal crowbar for closed white minds and insulated lives. Who knows why, in “The Upside,” Phillip picks the uncouth, underqualified Dell to drive him around, change his catheter and share his palatial apartment. But by the time the movie’s over, they’re paragliding together to Aretha Franklin. We’re told that this is based on a true story. It’s not. It’s a remake of a far more nauseating French megahit — “Les Intouchables” — and that claimed to be based on a true story. “The Upside” seems based on one of those paternalistic ’80s movies, “Disorderlies,” the one where the Fat Boys wheel an ailing Ralph Bellamy around his mansion. (…) Most of these black-white-friendship adventures were foretold by Mark Twain. Somebody is white Huck and somebody else is his amusingly dim black sidekick, Jim. This movie is just a little more flagrant about it. There’s a way of looking at the role reversal in “Green Book” as an upgrade. Through his record company, Don hires a white nightclub bouncer named Tony Vallelonga. (Most people call him Tony Lip.) We don’t meet Don for about 15 minutes, because the movie needs us to know that Tony is a sweet, Eye-talian tough guy who also throws out perfectly good glassware because his wife let black repairmen drink from it. By this point, you might have heard about the fried chicken scene in “Green Book.” It comes early in their road trip. Tony is shocked to discover that Don has never had fried chicken. He also appears never to have seen anybody eat fried chicken, either. (“What do we do about the bones?”) So, with all the greasy alacrity and exuberant crassness that Mortensen can conjure, Tony demonstrates how to eat it while driving. As comedy, it’s masterful — there’s tension, irony and, when the car stops and reverses to retrieve some litter, a punch line that brings down the house. But the comedy works only if the black, classical-pop fusion pianist is from outer space (and not in a Sun Ra sort of way). You’re meant to laugh because how could this racist be better at being black than this black man who’s supposed to be better than him? (…) The movie’s tagline is “based on a true friendship.” But the transactional nature of it makes the friendship seem less true than sponsored. So what does the money do, exactly? The white characters — the biological ones and somebody supposedly not black enough, like fictional Don — are lonely people in these pay-a-pal movies. The money is ostensibly for legitimate assistance, but it also seems to paper over all that’s potentially fraught about race. The relationship is entirely conscripted as service and bound by capitalism and the fantastically presumptive leap is, The money doesn’t matter because I like working for you. And if you’re the racist in the relationship: I can’t be horrible because we’re friends now. That’s why the hug Sandra Bullock gives Yomi Perry, the actor playing her maid, Maria, at the end of “Crash,” remains the single most disturbing gesture of its kind. It’s not friendship. Friendship is mutual. That hug is cannibalism. Money buys Don a chauffeur and, apparently, an education in black folkways and culture. (Little Richard? He’s never heard him play.) Shirley’s real-life family has objected to the portrait. Their complaints include that he was estranged from neither black people nor blackness. Even without that thumbs-down, you can sense what a particularly perverse fantasy this is: that absolution resides in a neutered black man needing a white guy not only to protect and serve him, but to love him, too. Even if that guy and his Italian-American family and mob associates refer to Don and other black people as eggplant and coal. In the movie’s estimation, their racism is preferable to its nasty, blunter southern cousin because their racism is often spoken in Italian. And, hey, at least Tony never asks Don to eat his fancy dinner in a supply closet. Mahershala Ali is acting Shirley’s isolation and glumness, but the movie determines that dining with racists is better than dining alone. The money buys Don relative safety, friendship, transportation and a walking-talking black college. What the money can’t buy him is more of the plot in his own movie. It can’t allow him to bask in his own unique, uniquely dreamy artistry. It can’t free him from a movie that sits him where Miss Daisy sat, yet treats him worse than Hoke. He’s a literal passenger on this white man’s trip. Tony learns he really likes black people. And thanks to Tony, now so does Don. Wesley Morris (NYT)

Today, our thousands of travelers, if they be thoughtful enough to arm themselves with a Green Book, may free themselves of a lot of worry and inconvenience as they plan a trip. Victor Hugo Green

Victor Hugo Green remains a mysterious figure about whom we know very little. He rarely spoke directly to Green Book readers, instead publishing testimonial letters in what the historian Cotten Seiler describes as an act of promotional “ventriloquism.” The debut edition did not exhort black travelers to boycotts or include demands for equal rights. Instead, Green represented the guide as a benign compilation of “facts and information connected with motoring, which the Negro Motorist can use and depend upon.” The coolly reasoned language put white readers at ease and allowed the Green Book to attract generous corporate and government sponsorship. Green nevertheless practiced the African-American art of coded communication, addressing black readers in messages that went over white peoples’ heads. Consider the passage: “Today, our thousands of travelers, if they be thoughtful enough to arm themselves with a Green Book, may free themselves of a lot of worry and inconvenience as they plan a trip.” White readers viewed this as a common-sense statement about vacation planning. For African-Americans who read in black newspapers about the fates that befell people like Ms. Derricotte, the notion of “arming” oneself with the guide referred to taking precautions against racism on the road. The Green Book was subversive in another way as well. It promoted an image of African-Americans that white Americans rarely saw — and that Hollywood deliberately avoided in films for fear of offending racist Southerners. The guide’s signature image, shown on the cover of the 1948 edition — and used as stationery logo for Victor Green, Inc. — consisted of a smiling, well-dressed couple striding toward their car carrying expensive suitcases. Green believed exposing white Americans to the black elite might persuade white business owners that black consumer spending was significant enough to make racial discrimination imprudent. Like the black elite itself, he subscribed to the view that affluent travelers of color could change white minds about racism simply by venturing to places where black people had been unseen. As it turned out, black travelers had a democratizing effect on the country. Like many African-American institutions that thrived during the age of extreme segregation, the Green Book faded in influence as racial barriers began to fall. It ceased publication not long after the Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed racial discrimination in public accommodations. Nevertheless, the guide’s three decades of listings offer an important vantage point on black business ownership and travel mobility in the age of Jim Crow. In other words, the Green Book has a lot more to say about the time when it was the Negro traveler’s bible. Grant Staples

Green Book, Sur les routes du Sud, c’est l’histoire (vraie) de la relation entre le pianiste de jazz afro-américain Don Shirley et le videur italo-américain Tony Lip – de son vrai nom Frank Anthony Vallelonga. Les deux hommes se retrouvent ensemble sur les routes de l’Amérique profonde : celle, ségrégationniste, du sud du pays, dans les années 60, à l’occasion d’une tournée de concerts. Le sophistiqué Don Shirley a besoin d’un chauffeur garde du corps alors que le bourru Tony Lip a besoin d’argent. Les deux hommes, respectivement incarnés par Mahershala Ali et Viggo Mortensen, tous deux impériaux, vont apprendre à s’apprivoiser malgré leurs préjugés respectifs (l’un, tendance raciste, sur les Noirs ; l’autre, tendance snob, sur les prolos.) (…) Le Negro Motorist Green Book était un guide indispensable quand on était un voyageur noir dans l’Amérique ségrégationniste. L’ouvrage, du nom de son auteur, le postier noir Victor H. Green, est publié tous les ans entre 1936 et 1966, et recense les motels, hôtels, bars, restaurants et stations-service où la clientèle de couleur est admise. Dans le film, Tony est contraint d’en faire usage pour trouver des endroits acceptant Don Shirley. (…) Green Book, qui vient de remporter trois Golden Globes (meilleur film, meilleur scénario et meilleur acteur dans un second rôle pour Mahershala Ali), se rendra aux Oscars, le 24 février prochain, fort de cinq nominations. Si la concurrence risque d’être rude face à Roma pour le meilleur film, ou à Christian Bale pour la statuette du meilleur acteur (il est époustouflant dans le rôle de Dick Cheney dans le film Vice, d’Adam McKay, en salle le 13 février), le film peut permettre à Mahershala Ali de rafler son deuxième oscar du meilleur second rôle, deux ans après celui qu’il a déjà obtenu pour Moonlight, de Barry Jenkins. (…) La famille de Don Shirley reproche aux scénariste d’avoir enjolivé, voire inventé la réalité, parlant d’une « symphonie de mensonges » : selon elle, les deux hommes ne sont pas devenus aussi amis que le film le laisse entendre, et Don Shirley n’était pas brouillé avec son frère. Les auteurs se défendent en affirmant avoir travaillé l’histoire avec Don Shirley lui-même. Certains critiques américains reprochent aussi au film de ne pas être « suffisamment noir » et de positionner le film depuis un point de vue blanc, comme Hollywood a tendance à le faire, sur le mode du white savior (« sauveur blanc »). Autre polémique, celle causée par diverses frasques de l’équipe : l’exhumation d’un tweet de Nick Vallelonga dans lequel il affirmait avoir vu des musulmans célébrer la chute des Twin Towers le 11 septembre 2001, confirmant ainsi des propos de Donald Trump, alors candidat à la présidence des Etats-Unis ; l’usage du « N word » (nigger) par Viggo Mortensen lors d’une interview, ou les excuse de Peter Farrelly qui a, dans le passé, montré son pénis « dans une tentative d’être drôle », notamment devant l’actrice Cameron Diaz. Autant de taches dans la cour aux Oscars… Télérama

Attention: une subversion peut en cacher une autre !

Au lendemain d’un Martin Luther King Day …

Où plus de 50 ans après sa mort l’on utilise son anniversaire pour appeler au boycott d’un Etat dont il avait défendu l’existence …

Et où sous prétexte de droits d’auteur et de protection de la vie privée, ses quatre enfants continuent à bloquer non seulement la libre circulation de ses discours historiques …

Mais, contraignant l’unique long-métrage Selma à la paraphrase et à la dissimulation des différends familiaux du Dr. King, la production de tout film sur l’ensemble de sa vie …

Et à la veille d’un triomphe annoncé (trois Golden Globes, cinq nominations aux Oscars, dont un 2e pour l’acteur principal) d’un film célébrant la mémoire d’un véritable génie de la musique noir …

Qui à l’instar du fameux petit Michelin noir de l’époque (le Green book du titre et du nom de son auteur, un certain Victor Hugo Green) et de sa petite élite noire d’utilsateurs …

Avait tant fait, via un courageux périple de 18 mois à travers un sud alors livré aux affres de la discrimination, pour en subvertir les bases …

Devinez qui, sous prétexte d’une amitié jugée exagérément présentée avec son chauffeur-garde du corps blanc et d’un climat historique jugé pas assez noir, est en train de torpiller la possibilité de pas moins de cinq oscars …

Pour une communauté afro-américaine qui par ailleurs ne manque pas de rappeler sa sous-représentation dans le cinéma américain ?

“Green Book” à livre ouvert : tout ce qu’il faut savoir sur ce favori des Oscars

Caroline Besse

Télérama

25/01/2019

Après avoir remporté trois Golden Globes, le film de Peter Farrelly est nominé cinq fois aux Oscars. Si vous avez aimé le duo formé par Viggo Mortensen et Mahershala Ali, voici l’occasion d’approfondir le sujet…

De quoi parle le film ?

Green Book, Sur les routes du Sud, c’est l’histoire (vraie) de la relation entre le pianiste de jazz afro-américain Don Shirley et le videur italo-américain Tony Lip – de son vrai nom Frank Anthony Vallelonga. Les deux hommes se retrouvent ensemble sur les routes de l’Amérique profonde : celle, ségrégationniste, du sud du pays, dans les années 60, à l’occasion d’une tournée de concerts.

Le sophistiqué Don Shirley a besoin d’un chauffeur garde du corps alors que le bourru Tony Lip a besoin d’argent. Les deux hommes, respectivement incarnés par Mahershala Ali et Viggo Mortensen, tous deux impériaux, vont apprendre à s’apprivoiser malgré leurs préjugés respectifs (l’un, tendance raciste, sur les Noirs ; l’autre, tendance snob, sur les prolos.)

Qui le réalise ?

Le réalisateur, Peter Farrelly, commet ici son premier film sans son frère Bobby. Après la série, dans les années 90, de comédies foutraques tendance scato et aujourd’hui cultes, Dumb et Dumber, Fous d’Irène ou Mary à tout prix, le cadet de la fratrie se lance dans la réalisation en solitaire de cette « dramédie » tendance buddy movie, en adaptant un scénario coécrit par Nick Vallelonga, le fils de Tony.

Qui est le vrai Tony Lip ?

C’est le genre d’homme qui a connu mille vies grâce à un bagout et à une tchatche hors du commun, qui lui ont d’ailleurs valu le surnom de « Lip » (« la lèvre » – de là où naît son talent de persuasion.) Son travail de videur dans le célèbre club new-yorkais The Copacabana, dans les années 60, lui a permis de rencontrer tout un tas de célébrités, dont Frank Sinatra ou Francis Ford Coppola. Ce dernier lui offre un rôle dans Le Parrain, en tant qu’invité du mariage. On le voit aussi dans Donnie Brasco, mais surtout dans la série Les Soprano, dans le rôle du mafieux à lunettes Carmine Lupertazzi. Il est mort en janvier 2013, trois mois avant Don Shirley.

Qu’est-ce qu’un « Green Book » ?

Le Negro Motorist Green Book était un guide indispensable quand on était un voyageur noir dans l’Amérique ségrégationniste. L’ouvrage, du nom de son auteur, le postier noir Victor H. Green, est publié tous les ans entre 1936 et 1966, et recense les motels, hôtels, bars, restaurants et stations-service où la clientèle de couleur est admise. Dans le film, Tony est contraint d’en faire usage pour trouver des endroits acceptant Don Shirley.

Quelles sont les chances du film aux Oscars ?

Green Book, qui vient de remporter trois Golden Globes (meilleur film, meilleur scénario et meilleur acteur dans un second rôle pour Mahershala Ali), se rendra aux Oscars, le 24 février prochain, fort de cinq nominations. Si la concurrence risque d’être rude face à Roma pour le meilleur film, ou à Christian Bale pour la statuette du meilleur acteur (il est époustouflant dans le rôle de Dick Cheney dans le film Vice, d’Adam McKay, en salle le 13 février), le film peut permettre à Mahershala Ali de rafler son deuxième oscar du meilleur second rôle, deux ans après celui qu’il a déjà obtenu pour Moonlight, de Barry Jenkins.

Quelle(s) polémiqu(e)s entourent le film ?

La famille de Don Shirley reproche aux scénariste d’avoir enjolivé, voire inventé la réalité, parlant d’une « symphonie de mensonges » : selon elle, les deux hommes ne sont pas devenus aussi amis que le film le laisse entendre, et Don Shirley n’était pas brouillé avec son frère. Les auteurs se défendent en affirmant avoir travaillé l’histoire avec Don Shirley lui-même.

Certains critiques américains reprochent aussi au film de ne pas être « suffisamment noir » et de positionner le film depuis un point de vue blanc, comme Hollywood a tendance à le faire, sur le mode du white savior (« sauveur blanc »).

Autre polémique, celle causée par diverses frasques de l’équipe : l’exhumation d’un tweet de Nick Vallelonga dans lequel il affirmait avoir vu des musulmans célébrer la chute des Twin Towers le 11 septembre 2001, confirmant ainsi des propos de Donald Trump, alors candidat à la présidence des Etats-Unis ; l’usage du « N word » (nigger) par Viggo Mortensen lors d’une interview, ou les excuse de Peter Farrelly qui a, dans le passé, montré son pénis « dans une tentative d’être drôle », notamment devant l’actrice Cameron Diaz. Autant de taches dans la cour aux Oscars…

Voir aussi:

The Green Book’s Black History

Lessons from the Jim Crow-era travel guide for African-American elites.

Brent Staples

NYT

Jan. 25, 2019

[The New York Times and Oculus are presenting a virtual-reality film, “Traveling While Black,” related to this Opinion essay. To view it, you can watch on the Oculus platform or download the NYT VR app on your mobile device.]

Imagine trudging into a hotel with your family at midnight — after a long, grueling drive — and being turned away by a clerk who “loses” your reservation when he sees your black face.

This was a common hazard for members of the African-American elite in 1932, the year Dr. B. Price Hurst of Washington, D.C., was shut out of New York City’s Prince George Hotel despite having confirmed his reservation by telegraph.

Hurst would have planned his trip differently had he been headed to the South, where “whites only” signs were ubiquitous and well-to-do black travelers lodged in homes owned by others in the black elite. Hurst was a member of Washington’s “Colored Four Hundred” — as the capital’s black upper crust once was known — and was familiar with having to plan his life around hotels, restaurants and theaters in the city, and throughout the Jim Crow South, that screened out people of color.

Hurst expected better of New York City. He did not let the matter rest after the Prince George turned his travel-weary family into the streets. He wrote an anguished letter to Walter White, then executive secretary of the N.A.A.C.P., explaining how he had been rejected by four hotels before shifting his search to the black district of Harlem. He then sued the Prince George for violating New York State’s civil rights laws, winning a settlement that put the city’s hotels on notice that discrimination could carry a financial cost.

African-Americans who embraced automobile travel to escape filthy, “colored-only” train cars learned quickly that the geography of Jim Crow was far more extensive than they had imagined. The motels and rest stops that deprived them of places to sleep were just the beginning.

While driving, these families were often forced to relieve themselves in roadside ditches because the filling stations that sold them gas barred them from using “whites only” bathrooms.

White motorists who drove clunkers deliberately damaged expensive cars driven by black people — to put Negroes “in their places.”

“Sundown Towns” across the country banned African-Americans from the streets after dark, a constant reminder that the reach of white supremacy was vast indeed.

As still happens today, police officers who pulled over motorists of color for “driving while black” raised the threat that black passengers would be arrested, battered or even killed during the encounter.

The Negro Traveler’s Bible

The Hurst case was a cause célèbre in 1936 when a Harlem resident and postal worker named Victor Hugo Green began soliciting material for a national travel guide that would steer black motorists around the humiliations of the not-so-open road and point them to businesses that were more than happy to accept colored dollars. As the historian Gretchen Sullivan Sorin writes in her revelatory study of “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” the guide became “the bible of every Negro highway traveler in the 1950s and early 1960s.”

Green, who died in 1960, is experiencing a renaissance thanks to heightened interest from filmmakers: The 2018 feature film “Green Book” won three Golden Globes earlier this month, and the documentary “Driving While Black” is scheduled for broadcast by PBS next year.

Then there is The New York Times opinion section’s Op-Doc film “Traveling While Black,” which debuts this Friday at the Sundance Film Festival. The brief film offers a revealing view of the Green Book era as told through Ben’s Chili Bowl, a black-owned restaurant in Washington, and reminds us that the humiliations heaped upon African-Americans during that time period extended well beyond the one Hurst suffered in New York City.

Sandra Butler-Truesdale, born in the capital in the 1930s, references an often-forgotten trauma — and one of the conceptual underpinnings of the Jim Crow era — when she recalls that Negroes who shopped in major stores were not allowed to try on clothing before they bought it. Store owners at the time offered a variety of racist rationales, including that Negroes were insufficiently clean. At bottom, the practice reflected the irrational belief that anything coming in contact with African-American skin — including clothing, silverware or bed linens — was contaminated by blackness, rendering it unfit for use by whites.

This had deadly implications in places where emergency medical services were assigned on the basis of race. Of all the afflictions devised in the Jim Crow era, medical racism was the most lethal. African-American accident victims could easily be left to die because no “black” ambulance was available. Black patients taken to segregated hospitals, where they sometimes languished in basements or even boiler rooms, suffered inferior treatment.

In a particularly telling case in 1931, the light-skinned father of Mr. White, the N.A.A.C.P. leader, was struck by a car and mistakenly admitted to the beautifully equipped “white” wing of Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. When relatives who were recognizably black came looking for him, hospital employees dragged the victim from the examination table to the decrepit Negro ward across the street, where he later died.

That same year, Juliette Derricotte, the celebrated African-American educator and dean of women at Fisk University, succumbed to injuries suffered in a car accident near Dalton, Ga., after a white hospital refused her treatment.

Advertising to the Black Elite

Victor Hugo Green remains a mysterious figure about whom we know very little. He rarely spoke directly to Green Book readers, instead publishing testimonial letters in what the historian Cotten Seiler describes as an act of promotional “ventriloquism.” The debut edition did not exhort black travelers to boycotts or include demands for equal rights. Instead, Green represented the guide as a benign compilation of “facts and information connected with motoring, which the Negro Motorist can use and depend upon.”

The coolly reasoned language put white readers at ease and allowed the Green Book to attract generous corporate and government sponsorship. Green nevertheless practiced the African-American art of coded communication, addressing black readers in messages that went over white peoples’ heads. Consider the passage: “Today, our thousands of travelers, if they be thoughtful enough to arm themselves with a Green Book, may free themselves of a lot of worry and inconvenience as they plan a trip.”

White readers viewed this as a common-sense statement about vacation planning. For African-Americans who read in black newspapers about the fates that befell people like Ms. Derricotte, the notion of “arming” oneself with the guide referred to taking precautions against racism on the road.

The Green Book was subversive in another way as well. It promoted an image of African-Americans that white Americans rarely saw — and that Hollywood deliberately avoided in films for fear of offending racist Southerners. The guide’s signature image, shown on the cover of the 1948 edition — and used as stationery logo for Victor Green, Inc. — consisted of a smiling, well-dressed couple striding toward their car carrying expensive suitcases.

Green believed exposing white Americans to the black elite might persuade white business owners that black consumer spending was significant enough to make racial discrimination imprudent. Like the black elite itself, he subscribed to the view that affluent travelers of color could change white minds about racism simply by venturing to places where black people had been unseen. As it turned out, black travelers had a democratizing effect on the country.

Like many African-American institutions that thrived during the age of extreme segregation, the Green Book faded in influence as racial barriers began to fall. It ceased publication not long after the Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed racial discrimination in public accommodations. Nevertheless, the guide’s three decades of listings offer an important vantage point on black business ownership and travel mobility in the age of Jim Crow.

In other words, the Green Book has a lot more to say about the time when it was the Negro traveler’s bible.

Voir enfin:

In many Oscar bait movies, interracial friendships come with a paycheck, and follow the white character’s journey to enlightenment.

CreditCreditPhoto illustration by Delphine Diallo for The New York Times; Universal Pictures, STX Films, Warner Bros. DreamWorks Pictures (Film stills)

Wesley Morris

NYT

“Driving Miss Daisy” is the sort of movie you know before you see it. The whole thing is right there in the poster. White Jessica Tandy is giving black Morgan Freeman a stern look, and he looks amused by her sternness. They’re framed in a rearview mirror, which occupies only about 20 percent of the space. You can make out his chauffeur’s cap and that she’s in the back seat. The rest is three actors’ names, a tag line, a title, tiny credits, and white space.

That rearview-mirror image isn’t a still from the movie but a warmly painted rendering of one, this vague nuzzling of Norman Rockwell Americana. And its warmth evokes a very particular past. If you’ve ever seen the packaging for Cream of Wheat or a certain brand of rice, if you’ve even seen some Shirley Temple movies, you knew how Miss Daisy would be driven: gladly.

As movie posters go, it’s ingeniously concise. But whoever designed it knew the concision was possible because we’d know the shorthand of an eternal racial dynamic. I got off the subway last month and saw a billboard of black Kevin Hart riding on the back of white Bryan Cranston’s motorized wheelchair. They’re both ecstatic. And maybe they’re obligated to be. Their movie is called “The Upside.” A few months before that, I was out getting a coffee when I saw a long, sexy billboard of white Viggo Mortensen driving black Mahershala Ali in a minty blue car for a movie called “Green Book.”

Not knowing what these movies were “about” didn’t mean it wasn’t clear what they were about. They symbolize a style of American storytelling in which the wheels of interracial friendship are greased by employment, in which prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of his white, frequently racist counterpart. All the optimism of racial progress — from desegregation to integration to equality to something like true companionship — is stipulated by terms of service. Thirty years separate “Driving Miss Daisy” from these two new films, but how much time has passed, really? The bond in all three is conditionally transactional, possible only if it’s mediated by money. “The Upside” has the rich, quadriplegic author Phillip Lacasse (Cranston) hire an ex-con named Dell Scott (Hart) to be his “life auxiliary.” “Green Book” reverses the races so that some white muscle (Mortensen) drives the black pianist Don Shirley (Ali) to gigs throughout the Deep South in the 1960s. It’s “The Upside Down.”

These pay-for-playmate transactions are a modern pastime, different from an entire history of popular culture that simply required black actors to serve white stars without even the illusion of friendship. It was really only possible in a post-integration America, possible after Sidney Poitier made black stardom loosely feasible for the white studios, possible after the moral and legal adjustments won during the civil rights movements, possible after the political recriminations of the black power and blaxploitation eras let black people regularly frolic among themselves for the first time since the invention of the Hollywood movie. Possible, basically, only in the 1980s, after the movements had more or less subsided and capitalism and jokey white paternalism ran wild.

On television in this era, rich white sitcom families vacuumed up little black boys, on “Diff’rent Strokes,” on “Webster.” On “Diff’rent Strokes,” the adopted boys are the orphaned Harlem sons of Phillip Drummond’s maid. Not only was money supposed to lubricate racial integration; it was perhaps supposed to mitigate a history of keeping black people apart and oppressed.

The sitcoms weren’t officially social experiments, but they were light advertisements for the civilizing (and alienating) benefits of white wealth on black life. The plot of “Trading Places,” from 1983, actually was an experiment, a pungent, complicated one, in which conniving white moneybags install a broke and hustling Eddie Murphy in disgraced Dan Aykroyd’s banking job. The scheme creates an accidental friendship between the duped pair and they both wind up rich.

But that Daddy Warbucks paternalism was how, in 1982, the owner of the country’s most ferocious comedic imagination — Richard Pryor — went from desperate janitor to live-in amusement for the bratty son of a rotten businessman (Jackie Gleason). You have to respect the bluntness of that one. The movie was called “The Toy,” and it’s simultaneously dumb, wild and appalling. I was younger than its little white protagonist (he’s “Master” Eric Bates) when I saw it, but I can still remember the look of embarrassed panic on Pryor’s face while he’s trapped in something called the Wonder Wheel. It’s a look that never quite goes away as he’s made to dress in drag, navigate the Ku Klux Klan and make Gleason feel good about his racism and terrible parenting.

These were relationships that continued the rules of the past, one in which Poitier was frequently hired to turn bigots into buddies. The rules didn’t need to be disguised by yesterday. These arrangements could flourish in the present. So maybe that was the alarming appeal of “Driving Miss Daisy.” It went there. It went back there. And people went for it. The movie came out at the end of 1989, won four Oscars (best picture, actress, adapted screenplay, makeup), got besotted reviews and made a pile of money. Why wasn’t a mystery.

Any time a white person comes anywhere close to the rescue of a black person the academy is primed to say, “Good for you!,” whether it’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Mississippi Burning,” “The Blind Side,” or “The Help.” The year “Driving Miss Daisy” won those Oscars, Morgan Freeman also had a supporting role in a drama (“Glory”) that placed a white Union colonel at its center and was very much in the mix that night. (Denzel Washington won his first Oscar for playing a slave-turned-Union soldier in that movie.) And Spike Lee lost the original screenplay award for “Do the Right Thing,” his masterpiece about a boiled-over pot of racial animus in Brooklyn. I was 14 then, and the political incongruity that night was impossible not to feel. “Driving Miss Daisy” and “Glory” were set in the past and the people who loved them seemed stuck there. The giddy reception for “Miss Daisy” seemed earnest. But Lee’s movie dramatized a starker truth — we couldn’t all just get along.

For what it’s worth, Lee is now up for more Oscars. His film “BlacKkKlansman” has six nominations. Given the five for “Green Book,” basically so is “Driving Miss Daisy.” Which is to say that 2019 might just be 1990 all over again. And yet viewed separately from the cold shower of “Do the Right Thing,” “Driving Miss Daisy” does operate with more finesse, elegance and awareness than my teenage self wanted to see. It’s still not the best movie of 1989. But it does know the southern caste system and the premium that system placed on propriety.

The movie turns the 25-year relationship between Daisy, an elderly Jewish white widow from Atlanta, and Hoke, her elderly, widowed black driver, into both this delicate, modest, tasteful thing — a love letter, a corsage — and something amusingly perverse. Proud old prejudiced Daisy says she doesn’t want to be driven anywhere. But doesn’t she? Hoke treats her pride like a costume. He stalks her with her own new car until she succumbs and lets him drive her to the market. What passes between them feels weirdly kinky: southern-etiquette S&M.

Bruce Beresford directed the movie and Alfred Uhry based it on his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, which he said was inspired by his grandmother and her chauffeur, and it does powder over the era’s upheavals, uprisings and blowups. But it doesn’t sugarcoat the history fueling the regional and national climes, either. Daisy’s fortune comes from cotton, and Hoke, with ruthless affability, keeps reminding her that she’s rich. When she says things are a-changing, he tells her not that much.

Platonic love blossoms, obviously. But the movie’s one emotional gaffe would seem to come near the end when Daisy grabs Hoke’s hand and tells him so. “You’re my best friend,” she creaks. But her admission arises not from one of their little S&M drives but after a bout of dementia. And in a wide shot, he stands above her, a little stooped, halfway in, halfway out, moved yet confused. And in his posture resides an entire history of national racial awkwardness: He has to mind his composure even as she’s losing her mind.

One headache with these movies, even one as well done as “Driving Miss Daisy,” is that they romanticize their workplaces and treat their black characters as the ideal crowbar for closed white minds and insulated lives.

Who knows why, in “The Upside,” Phillip picks the uncouth, underqualified Dell to drive him around, change his catheter and share his palatial apartment. But by the time the movie’s over, they’re paragliding together to Aretha Franklin. We’re told that this is based on a true story. It’s not. It’s a remake of a far more nauseating French megahit — “Les Intouchables” — and that claimed to be based on a true story. “The Upside” seems based on one of those paternalistic ’80s movies, “Disorderlies,” the one where the Fat Boys wheel an ailing Ralph Bellamy around his mansion.

Phillip’s largess and tolerance take Dell from opera-phobic to opera-curious to opera queen, leading to Dell’s being able to afford to transport his ex and their son out of the projects, and permitting Dell to take his boss’s luxury cars for a spin whether or not he’s riding shotgun. And Dell provides entertainment (and drugs) that ease Phillip’s sense of isolation and self-consciousness. But this is also a movie that needs Dell to steal one of Phillip’s antique first-editions as a surprise gift to his estranged son, and not a copy of some Judith Krantz or Sidney Sheldon novel, either. He swipes “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (and to reach it, his hand has to skip past a few Horatio Alger books, too). Most of these black-white-friendship adventures were foretold by Mark Twain. Somebody is white Huck and somebody else is his amusingly dim black sidekick, Jim. This movie is just a little more flagrant about it.

There’s a way of looking at the role reversal in “Green Book” as an upgrade. Through his record company, Don hires a white nightclub bouncer named Tony Vallelonga. (Most people call him Tony Lip.) We don’t meet Don for about 15 minutes, because the movie needs us to know that Tony is a sweet, Eye-talian tough guy who also throws out perfectly good glassware because his wife let black repairmen drink from it.

By this point, you might have heard about the fried chicken scene in “Green Book.” It comes early in their road trip. Tony is shocked to discover that Don has never had fried chicken. He also appears never to have seen anybody eat fried chicken, either. (“What do we do about the bones?”) So, with all the greasy alacrity and exuberant crassness that Mortensen can conjure, Tony demonstrates how to eat it while driving. As comedy, it’s masterful — there’s tension, irony and, when the car stops and reverses to retrieve some litter, a punch line that brings down the house. But the comedy works only if the black, classical-pop fusion pianist is from outer space (and not in a Sun Ra sort of way). You’re meant to laugh because how could this racist be better at being black than this black man who’s supposed to be better than him?

The movie Peter Farrelly directed and wrote, with Brian Currie and Tony’s son Nick, is suspiciously like “Driving Miss Daisy,” but same-sex, with Don as Daisy and Tony as Hoke. Indeed, “Miss Daisy” features a fried chicken scene, too, a delicate one, in which Hoke tells her the flame is too high on the skillet and she waves him off. Once he’s left the kitchen, she furtively, begrudgingly adjusts the burner. It’s like Farrelly watched that scene and thought it needed a stick of cartoon dynamite.

Before they head out, a white character from Don’s record company gives Tony a listing of black-friendly places to house Don: The Green Book. The idea for “The Negro Motorist Green Book” belongs to Victor Hugo Green, a postal worker, who introduced it in 1936. It guided black road trippers to stress-free gas, food and lodging in the segregated South. The story of its invention, distribution and updating is an amusing, invigorating, poignant and suspenseful story of an astonishing social network, and warrants a movie in itself. In the meantime, what does Tony need a Green Book for? He is the Green Book.

The movie’s tagline is “based on a true friendship.” But the transactional nature of it makes the friendship seem less true than sponsored. So what does the money do, exactly? The white characters — the biological ones and somebody supposedly not black enough, like fictional Don — are lonely people in these pay-a-pal movies. The money is ostensibly for legitimate assistance, but it also seems to paper over all that’s potentially fraught about race. The relationship is entirely conscripted as service and bound by capitalism and the fantastically presumptive leap is, The money doesn’t matter because I like working for you. And if you’re the racist in the relationship: I can’t be horrible because we’re friends now. That’s why the hug Sandra Bullock gives Yomi Perry, the actor playing her maid, Maria, at the end of “Crash,” remains the single most disturbing gesture of its kind. It’s not friendship. Friendship is mutual. That hug is cannibalism.

Money buys Don a chauffeur and, apparently, an education in black folkways and culture. (Little Richard? He’s never heard him play.) Shirley’s real-life family has objected to the portrait. Their complaints include that he was estranged from neither black people nor blackness. Even without that thumbs-down, you can sense what a particularly perverse fantasy this is: that absolution resides in a neutered black man needing a white guy not only to protect and serve him, but to love him, too. Even if that guy and his Italian-American family and mob associates refer to Don and other black people as eggplant and coal. In the movie’s estimation, their racism is preferable to its nasty, blunter southern cousin because their racism is often spoken in Italian. And, hey, at least Tony never asks Don to eat his fancy dinner in a supply closet.

Mahershala Ali is acting Shirley’s isolation and glumness, but the movie determines that dining with racists is better than dining alone. The money buys Don relative safety, friendship, transportation and a walking-talking black college. What the money can’t buy him is more of the plot in his own movie. It can’t allow him to bask in his own unique, uniquely dreamy artistry. It can’t free him from a movie that sits him where Miss Daisy sat, yet treats him worse than Hoke. He’s a literal passenger on this white man’s trip. Tony learns he really likes black people. And thanks to Tony, now so does Don.

Lately, the black version of these interracial relationships tends to head in the opposite direction. In the black version, for one thing, they’re not about money or a job but about the actual emotional, psychological work of being black among white people. Here, the proximity to whiteness is toxic, a danger, a threat. That’s the thrust of Jeremy O. Harris’s stage drama “Slave Play,” in which the traumatic legacy of plantation life pollutes the black half of the show’s interracial relationships. That’s a particularly explicit, ingenious example. But scarcely any of the work I’ve seen in the last year by black artists — not Jackie Sibblies Drury’s equally audacious play “Fairview,” not Boots Riley’s “Sorry to Bother You,” not “Blindspotting,” which Daveed Diggs co-wrote and stars in, not Barry Jenkins’s “If Beale Street Could Talk” or Ryan Coogler’s “Black Panther” — emphasizes the smoothness and joys of interracial friendship and certainly not through employment. The health of these connections is iffy, at best.

In 1989, Lee was pretty much on his own as a voice of black racial reality. His rankled pragmatism now has company and, at the Academy Awards, it’s also got stiff competition. He helped plant the seeds for an environment in which black artists can look askance at race. But a lot of us still need the sense of fantastical racial contentment that movies like “The Upside” and “Green Book” are slinging. I’ve seen “Green Book” with paying audiences, and it cracks people up the way any of Farrelly’s comedies do. The kind of closure it offers is like a drug that Lee’s never dealt. The Charlottesville-riot footage that he includes as an epilogue in “BlacKkKlansman” might bury the loose, essentially comedic movie it’s attached to in furious lava. Lee knows the past too well to ever let the present off the hook. The volcanoes in this country have never been dormant.

The academy’s embrace of Lee at this stage of his career (this is his first best director nomination) suggests that it’s come around to what rankles him. Of course, “BlacKkKlansman” is taking on the unmistakable villainy of the KKK in the 1970s. But what put Lee on the map 30 years ago was his fearlessness about calling out the universal casual bigotry of the moment, like Daisy’s and Tony’s. It’s hot as hell in “Do the Right Thing,” and in the heat, almost everybody has a problem with who somebody is. The pizzeria owned by Sal (Danny Aiello) comes to resemble a house of hate. Eventually Sal’s delivery guy, Mookie (played by Lee), incites a melee by hurling a trash can through the store window. He’d already endured a conversation with Pino (John Turturro), Sal’s racist son, in which he tells Mookie that famous black people are “more than black.”

Closure is impossible because the blood is too bad, too historically American. Lee had conjured a social environment that’s the opposite of what “The Upside,” “Green Book,” and “Driving Miss Daisy” believe. In one of the very last scenes, after Sal’s place is destroyed, Mookie still demands to be paid. To this day, Sal’s tossing balled-up bills at Mookie, one by one, shocks me. He’s mortally offended. Mookie’s unmoved. They’re at a harsh, anti-romantic impasse. We’d all been reared on racial-reconciliation fantasies. Why can’t Mookie and Sal be friends? The answer’s too long and too raw. Sal can pay Mookie to deliver pizzas ‘til kingdom come. But he could never pay him enough to be his friend.

A New Hope

Can ‘Belle’ End Hollywood’s Obsession with the White Savior?

The black characters in films like ‘The Help’ and ’12 Years A Slave’ always seem to need a white knight. But the black protagonist in ‘Belle,’ a new film about racism and slavery in England, takes matters into her own hands.

The film Belle, which opens this weekend in limited release stateside, is inspired by a true story, deals with the horrors of the African slave trade, and its director is black and British. For these reasons, comparisons to the recent recipient of the Best Picture Oscar, 12 Years a Slave, are inevitable.

But there are some notable differences.

Among them, Belle is set in England, while 12 Years a Slave is set in America. 12 Years a Slave depicts—in unflinching detail—the brutalities of slavery, while Belle merely hints at its physical and psychological toll. But the most significant deviation is this: whereas 12 Years a Slave faced criticism for being yet another film to perpetuate the “white savior” cliché in cinema, in Belle, the beleaguered black protagonist does something novel: she saves herself.

“Belle marks the first film I’ve seen in which a black woman with agency stands at the center of the plot as a full, eloquent human being who is neither adoring foil nor moral touchstone for her better spoken white counterparts,” the novelist and TV producer Susan Fales-Hill told The Daily Beast.

Directed by the Amma Asante, the film is inspired by the 1779 painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle, a mixed race woman in a turban hauling fruit, and her white cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray. The artwork was commissioned by William Murray, acting Lord Chief Justice of England, and depicts the two nieces smiling with Murray’s hand resting on Belle’s waist—a gesture suggesting equality, not subservience. While its artist is unknown, the portrait hung in England’s Kenwood House, alongside works by Vermeer and Rembrandt, until 1922.

The painting’s mysterious subject, Belle, was the daughter of an African slave known as Maria Belle and Admiral Sir John Lindsay, an English aristocrat. She was ultimately raised by Lindsay’s uncle, William Murray, the aforementioned Lord Chief Justice and 1st Earl of Mansfield, with many of the privileges befitting a woman of her family’s high standing. Since not much is known of Belle’s life inside the Mansfield estate, Asante and screenwriter Misan Sagay took some artistic license in dramatizing the dehumanizing racial prejudice their protagonist endured that even her social standing and wealth could not erase.

For instance, while not permitted to dine with the servants of her home since they were considered beneath her, she was also not permitted to dine with her family when guests were present since she was considered beneath them. This racial balancing act makes Belle one of the most genteel yet uncomfortable depictions of racism ever to grace the screen. Here, the racism isn’t as black-and-white—those providing Belle with her luxury attire, emotional affection, and protection from the racial brutality of the outside world also see her as a lesser being.

“For me, this point of view is so refreshing,” Gugu Mbatha-Raw, who plays Belle, told The Daily Beast. “I’d never seen a period drama like this with a woman of color as the lead who wasn’t being brutalized, wasn’t being raped, was going through this personal evolution but was also in a privileged world and articulate and educated. I just hadn’t seen that on film before.”

Indeed, Belle becomes empowered to challenge the white characters that view themselves as her savior on their veiled racism, which marks a welcome departure from one of Hollywood’s most enduring cinematic tropes: the white savior.

When it comes to race-relations dramas—and slavery narratives, in particular—the white savior has become one of Hollywood’s most reliably offensive clichés. The black servants of The Help needed a perky, progressive Emma Stone to shed light on their plight; the football bruiser in The Blind Side couldn’t have done it without fiery Sandra Bullock; the black athletes in Cool Runnings and The Air Up There needed the guidance of their white coach; and in 12 Years A Slave, Solomon Northup, played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, is liberated at the eleventh hour by a Jesus-looking Brad Pitt (in a classic Deus Ex Machina).

“I think it’s a trope that has certainly been seen in Hollywood films for decades,” longtime film critic Laurence Lerman, formerly of Variety, says. “Think about the white teacher in the inner city school. The Michelle Pfeiffer one [in Dangerous Minds]. The Principal. Music of the Heart, where Meryl Streep was a music teacher. Wildcats. I think these stories probably read well in a pitch meeting: ‘Goldie Hawn coaching an inner city football team.’”

But, as he went on to explain, the execution often leaves something to be desired and doesn’t always reflect well on the communities it depicts—ones rooted in chaos that need a white savior to restore order. Lerman further noted that this cinematic trope is not limited to the depiction of inner cities or black people. Of the Last Samurai he said, “They make it look like Japan would not have made it out of the feudal period without Tom Cruise.” And the worst offender, in his opinion, is Dances with Wolves. “The west wouldn’t have been tamed and we’d have no civilization if Kevin Costner didn’t ride into town,” he says sarcastically.