On ne peut pas dire ce mot commençant par N [nègre], je ne veux pas l’utiliser, mais il n’est pas rare que des gens se disant progressistes utilisent ce mot commençant par la lettre R, redneck, “plouc”. Résident de Louisiane

On ne peut pas dire ce mot commençant par N [nègre], je ne veux pas l’utiliser, mais il n’est pas rare que des gens se disant progressistes utilisent ce mot commençant par la lettre R, redneck, “plouc”. Résident de Louisiane

Ainsi les derniers seront les premiers et les premiers seront les derniers. Jésus (Matthieu 20: 16)

The line it is drawn, the curse it is cast. The slow one now will later be fast as the present now will later be past. The order is rapidly fadin’ and the first one now will later be last for the times they are a-changin. Bob Dylan

Un peuple connait, aime et défend toujours plus ses moeurs que ses lois. Montesquieu

Aux États-Unis, les plus opulents citoyens ont bien soin de ne point s’isoler du peuple ; au contraire, ils s’en rapprochent sans cesse, ils l’écoutent volontiers et lui parlent tous les jours. Alexis de Tocqueville

L’essentiel est d’être bon aux gens avec qui l’on vit. (…) Défiez-vous de ces cosmopolites qui vont chercher au loin dans leurs livres des devoirs qu’ils dédaignent de remplir autour d’eux. Tel philosophe aime les Tartares, pour être dispensé d’aimer ses voisins. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (L’Emile, 1762)

Bien sûr, nous sommes résolument cosmopolites. Bien sûr, tout ce qui est terroir, béret, bourrées, binious, bref franchouillard ou cocardier, nous est étranger, voire odieux. Bernard-Henri Lévy (profession de foi du premier numéro du journal Globe, 1985)

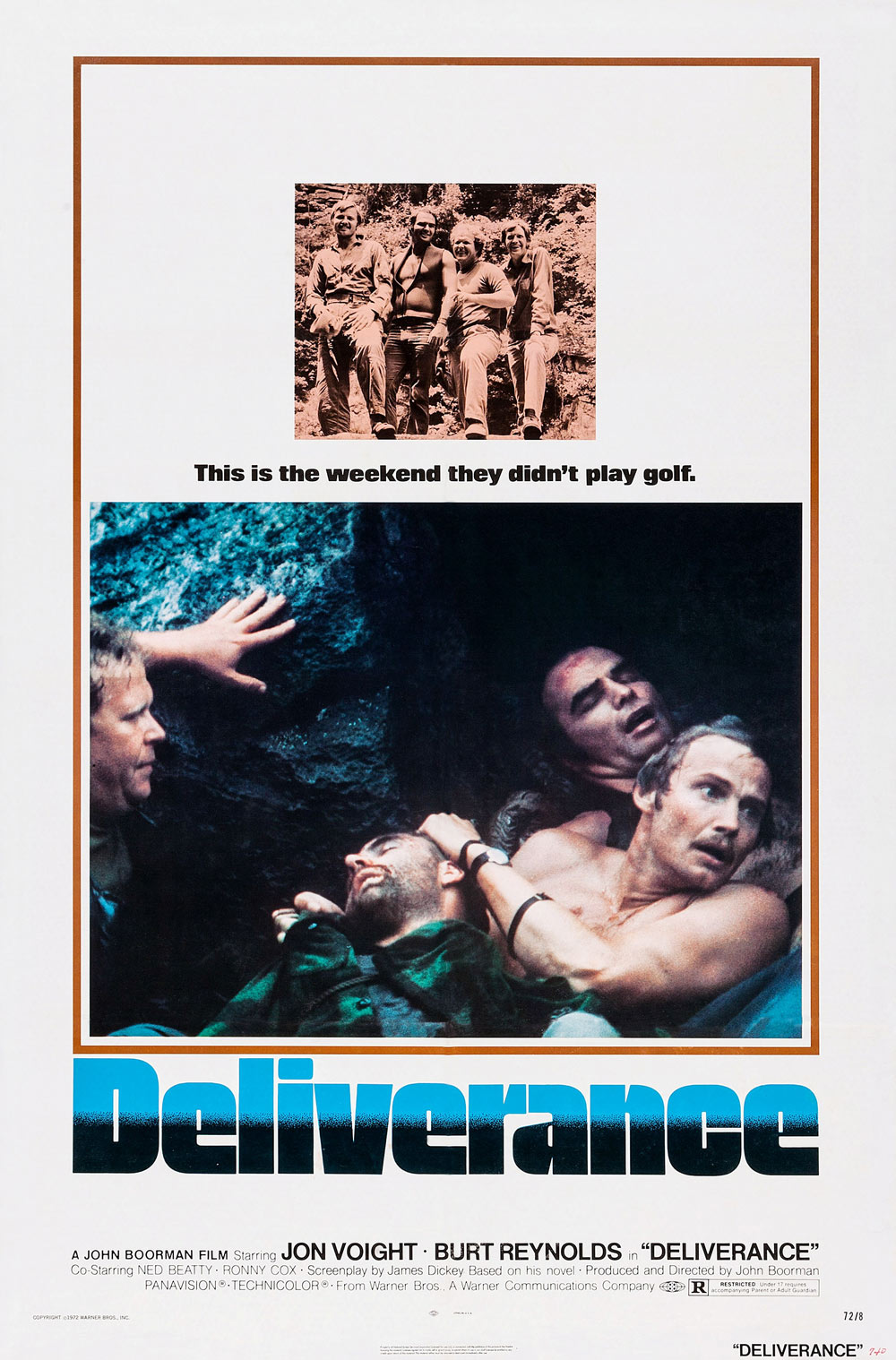

Deliverance did for them what Jaws, another well-known movie, would later do for sharks. Daniel Roper (North Georgia Journal)

Depuis que la gauche a adopté l’économie de marché, il ne lui reste qu’une chose à faire pour garder sa posture de gauche : lutter contre un fascisme qui n’existe pas. Pasolini

J’ai résumé L’Étranger, il y a longtemps, par une phrase dont je reconnais qu’elle est très paradoxale : “Dans notre société tout homme qui ne pleure pas à l’enterrement de sa mère risque d’être condamné à mort.” Je voulais dire seulement que le héros du livre est condamné parce qu’il ne joue pas le jeu. En ce sens, il est étranger à la société où il vit, où il erre, en marge, dans les faubourgs de la vie privée, solitaire, sensuelle. Et c’est pourquoi des lecteurs ont été tentés de le considérer comme une épave. On aura cependant une idée plus exacte du personnage, plus conforme en tout cas aux intentions de son auteur, si l’on se demande en quoi Meursault ne joue pas le jeu. La réponse est simple : il refuse de mentir. (…) Meursault, pour moi, n’est donc pas une épave, mais un homme pauvre et nu, amoureux du soleil qui ne laisse pas d’ombres. Loin qu’il soit privé de toute sensibilité, une passion profonde parce que tenace, l’anime : la passion de l’absolu et de la vérité. Il s’agit d’une vérité encore négative, la vérité d’être et de sentir, mais sans laquelle nulle conquête sur soi et sur le monde ne sera jamais possible. On ne se tromperait donc pas beaucoup en lisant, dans L’Étranger, l’histoire d’un homme qui, sans aucune attitude héroïque, accepte de mourir pour la vérité. Il m’est arrivé de dire aussi, et toujours paradoxalement, que j’avais essayé de figurer, dans mon personnage, le seul Christ que nous méritions. On comprendra, après mes explications, que je l’aie dit sans aucune intention de blasphème et seulement avec l’affection un peu ironique qu’un artiste a le droit d’éprouver à l’égard des personnages de sa création. Camus (préface américaine à L’Etranger)

Le thème du poète maudit né dans une société marchande (…) s’est durci dans un préjugé qui finit par vouloir qu’on ne puisse être un grand artiste que contre la société de son temps, quelle qu’elle soit. Légitime à l’origine quand il affirmait qu’un artiste véritable ne pouvait composer avec le monde de l’argent, le principe est devenu faux lorsqu’on en a tiré qu’un artiste ne pouvait s’affirmer qu’en étant contre toute chose en général. Albert Camus

Personne ne nous fera croire que l’appareil judiciaire d’un Etat moderne prend réellement pour objet l’extermination des petits bureaucrates qui s’adonnent au café au lait, aux films de Fernandel et aux passades amoureuses avec la secrétaire du patron. René Girard

Toutes les stratégies que les intellectuels et les artistes produisent contre les « bourgeois » tendent inévitablement, en dehors de toute intention expresse et en vertu même de la structure de l’espace dans lequel elles s’engendrent, à être à double effet et dirigées indistinctement contre toutes les formes de soumission aux intérêts matériels, populaires aussi bien que bourgeoises. Bourdieu

Il y a autant de racismes qu’il y a de groupes qui ont besoin de se justifier d’exister comme ils existent, ce qui constitue la fonction invariante des racismes. Il me semble très important de porter l’analyse sur les formes du racisme qui sont sans doute les plus subtiles, les plus méconnaissables, donc les plus rarement dénoncées, peut-être parce que les dénonciateurs ordinaires du racisme possèdent certaines des propriétés qui inclinent à cette forme de racisme. Je pense au racisme de l’intelligence. (…) Ce racisme est propre à une classe dominante dont la reproduction dépend, pour une part, de la transmission du capital culturel, capital hérité qui a pour propriété d’être un capital incorporé, donc apparemment naturel, inné. Le racisme de l’intelligence est ce par quoi les dominants visent à produire une « théodicée de leur propre privilège », comme dit Weber, c’est-à-dire une justification de l’ordre social qu’ils dominent. (…) Tout racisme est un essentialisme et le racisme de l’intelligence est la forme de sociodicée caractéristique d’une classe dominante dont le pouvoir repose en partie sur la possession de titres qui, comme les titres scolaires, sont censés être des garanties d’intelligence et qui ont pris la place, dans beaucoup de sociétés, et pour l’accès même aux positions de pouvoir économique, des titres anciens comme les titres de propriété et les titres de noblesse. Pierre Bourdieu

What I take to be the film’s statement (upper case). This has to do with the threat that people like the nonconforming Wyatt and Billy represent to the ordinary, self-righteous, inhibited folk that are the Real America. Wyatt and Billy, says the lawyer, represent freedom; ergo, says the film, they must be destroyed. If there is any irony in this supposition, I was unable to detect it in the screenplay written by Fonda, Hopper and Terry Southern. Wyatt and Billy don’t seem particularly free, not if the only way they can face the world is through a grass curtain. As written and played, they are lumps of gentle clay, vacuous, romantic symbols, dressed in cycle drag. The NYT (1969)

Since Easy Rider is the film that is said finally to separate the men from the boys – at a time when the generation gap has placed a stigma on being a man – I want to point out that those who make heroes of Wyatt and Billy (played by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper) have a reasonably acrid dose to swallow at the start of the picture. Wyatt and Billy (names borrowed from the fumigated memory of the two outlaws of the Old West) make the bankroll on which they hope to live a life of easy-riding freedom by smuggling a considerable quantity of heroin across from Mexico and selling it to a nutty looking addict in a goon-chauffered Rolls Royce. Pulling off one big job and thereafter living in virtuous indolence is a fairly common dream of criminals, and dope peddling is a particularly unappetizing way of doing it. Is it thought O.K. on the other side of the gap, to buy freedom at that price? If so, grooving youth has a wealth of conscience to spend. (…) Wyatt and Billy are presented as attractive and enviable; gentle, courteous, peaceable, sliding through the heroic Western landscape on their luxurious touring motorcycles (with the swag hidden in one of the gas tanks). It is true that they come to a bloody end, gunned down by a couple of Southern rednecks for their long hair. But it is not retribution; indeed, they might have passed safely if the cretins in the pickup truck had realized that they were big traders on holiday. (…) The hate is that of Fonda, Hopper and Southern, they hate the element in American life that tries to destroy anyone who fails to conform, who demands to ride free. And it is quite right that they should. But Wyatt and Billy are more rigidly conformist, their life more narrowly obsessive than that of any broker’s clerk on the nine to five. The Nation (2008)

Easy Rider (1969) is the late 1960s « road film » tale of a search for freedom (or the illusion of freedom) in a conformist and corrupt America, in the midst of paranoia, bigotry and violence. Released in the year of the Woodstock concert, and made in a year of two tragic assassinations (Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King), the Vietnam War buildup and Nixon’s election, the tone of this ‘alternative’ film is remarkably downbeat and bleak, reflecting the collapse of the idealistic 60s. Easy Rider, one of the first films of its kind, was a ritualistic experience and viewed (often repeatedly) by youthful audiences in the late 1960s as a reflection of their realistic hopes of liberation and fears of the Establishment. The iconographic, ‘buddy’ film, actually minimal in terms of its artistic merit and plot, is both memorialized as an image of the popular and historical culture of the time and a story of a contemporary but apocalyptic journey by two self-righteous, drug-fueled, anti-hero (or outlaw) bikers eastward through the American Southwest. Their trip to Mardi Gras in New Orleans takes them through limitless, untouched landscapes (icons such as Monument Valley), various towns, a hippie commune, and a graveyard (with hookers), but also through areas where local residents are increasingly narrow-minded and hateful of their long-haired freedom and use of drugs. The film’s title refers to their rootlessness and ride to make « easy » money; it is also slang for a pimp who makes his livelihood off the earnings of a prostitute. However, the film’s original title was The Loners. [The names of the two main characters, Wyatt and Billy, suggest the two memorable Western outlaws Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid – or ‘Wild Bill’ Hickcock. Rather than traveling westward on horses as the frontiersmen did, the two modern-day cowboys travel eastward from Los Angeles – the end of the traditional frontier – on decorated Harley-Davidson choppers on an epic journey into the unknown for the ‘American dream’.] According to slogans on promotional posters, they were on a search: A man went looking for America and couldn’t find it anywhere… Their costumes combine traditional patriotic symbols with emblems of loneliness, criminality and alienation – the American flag, cowboy decorations, long-hair, and drugs. (…) Easy Rider surprisingly, was an extremely successful, low-budget (under $400,000), counter-cultural, independent film for the alternative youth/cult market – one of the first of its kind that was an enormous financial success, grossing $40 million worldwide. Its story contained sex, drugs, casual violence, a sacrificial tale (with a shocking, unhappy ending), and a pulsating rock and roll soundtrack reinforcing or commenting on the film’s themes. Groups that participated musically included Steppenwolf, Jimi Hendrix, The Band and Bob Dylan. The pop cultural, mini-revolutionary film was also a reflection of the « New Hollywood, » and the first blockbuster hit from a new wave of Hollywood directors (e.g., Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, and Martin Scorsese) that would break with a number of Hollywood conventions. It had little background or historical development of characters, a lack of typical heroes, uneven pacing, jump cuts and flash-forward transitions between scenes, an improvisational style and mood of acting and dialogue, background rock ‘n’ roll music to complement the narrative, and the equation of motorbikes with freedom on the road rather than with delinquent behaviors. However, its idyllic view of life and example of personal film-making was overshadowed by the self-absorbent, drug-induced, erratic behavior of the filmmakers, chronicled in Peter Biskind’s tell-all Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and Rock ‘N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (1999). And the influential film led to a flurry of equally self-indulgent, anti-Establishment themed films by inferior filmmakers, who overused some of the film’s technical tricks and exploited the growing teen-aged market for easy profits. (…) Death seems to be the only freedom or means to escape from the system in America where alternative lifestyles and idealism are despised as too challenging or free. The romance of the American highway is turned menacing and deadly. Filmsite

Nous qui vivons dans les régions côtières des villes bleues, nous lisons plus de livres et nous allons plus souvent au théâtre que ceux qui vivent au fin fond du pays. Nous sommes à la fois plus sophistiqués et plus cosmopolites – parlez-nous de nos voyages scolaires en Chine et en Provence ou, par exemple, de notre intérêt pour le bouddhisme. Mais par pitié, ne nous demandez pas à quoi ressemble la vie dans l’Amérique rouge. Nous n’en savons rien. Nous ne savons pas qui sont Tim LaHaye et Jerry B. Jenkins. […] Nous ne savons pas ce que peut bien dire James Dobson dans son émission de radio écoutée par des millions d’auditeurs. Nous ne savons rien de Reba et Travis. […] Nous sommes très peu nombreux à savoir ce qui se passe à Branson dans le Missouri, même si cette ville reçoit quelque sept millions de touristes par an; pas plus que nous ne pouvons nommer ne serait-ce que cinq pilotes de stock-car. […] Nous ne savons pas tirer au fusil ni même en nettoyer un, ni reconnaître le grade d’un officier rien qu’à son insigne. Quant à savoir à quoi ressemble une graine de soja poussée dans un champ… David Brooks

Vous allez dans certaines petites villes de Pennsylvanie où, comme ans beaucoup de petites villes du Middle West, les emplois ont disparu depuis maintenant 25 ans et n’ont été remplacés par rien d’autre (…) Et il n’est pas surprenant qu’ils deviennent pleins d’amertume, qu’ils s’accrochent aux armes à feu ou à la religion, ou à leur antipathie pour ceux qui ne sont pas comme eux, ou encore à un sentiment d’hostilité envers les immigrants. Barack Hussein Obama (2008)

Part of the reason that our politics seems so tough right now, and facts and science and argument does not seem to be winning the day all the time, is because we’re hard-wired not to always think clearly when we’re scared. Barack Obama

I do think that when you combine that demographic change with all the economic stresses that people have been going through because of the financial crisis, because of technology, because of globalization, the fact that wages and incomes have been flatlining for some time, and that particularly blue-collar men have had a lot of trouble in this new economy, where they are no longer getting the same bargain that they got when they were going to a factory and able to support their families on a single paycheck. You combine those things, and it means that there is going to be potential anger, frustration, fear. Some of it justified, but just misdirected. I think somebody like Mr. Trump is taking advantage of that. That’s what he’s exploiting during the course of his campaign. Barack Hussein Obama

Pour généraliser, en gros, vous pouvez placer la moitié des partisans de Trump dans ce que j’appelle le panier des pitoyables. Les racistes, sexistes, homophobes, xénophobes, islamophobes. A vous de choisir. Hillary Clinton (2016)

My mother is not watching. She said she doesn’t watch white award shows because you guys don’t thank Jesus enough. That’s true. The only white people that thank Jesus are Republicans and ex-crackheads. Michael Che

Populism might even be seen as idealistic, another wing of ‘post-materialistic’ politics more normally associated with the environmental movement; a quest for meaning and collective identity in a secular, individualistic modern world. When people in Sunderland voted for Brexit apparently against their material interests it was considered stupid; when affluent people vote for higher taxes it is considered admirable. David Goodhart

The Remain campaign was all about money and how much people would lose if Britain exited the EU. The Leave campaign was all about restoring a semblance of meaning to people’s lives, despite not having much money. As a vote for something more than money – for pride, belonging, community, identity, a sense of “home” – it was a rejection of the market. We might not much like some elements of this “vote for meaning”, but it was a vote with the heart, rather than the wallet. The result was a reminder that people need something in their lives that feels more important than money – especially, perhaps, when they have little prospect of having much. Charles Leadbeater

Rire général, même chez les sans-dents. François Hollande

Dans les sociétés dans mes dossiers, il y a la société Gad : il y a dans cet abattoir une majorité de femmes, il y en a qui sont pour beaucoup illettrées ! On leur explique qu’elles n’ont plus d’avenir à Gad et qu’elles doivent aller travailler à 60 km ! Ces gens n’ont pas le permis ! On va leur dire quoi ? Il faut payer 1.500 euros et attendre un an ? Voilà, ça ce sont des réformes du quotidien, qui créent de la mobilité, de l’activité ! Emmanuel Macron

On ne va pas s’allier avec le FN, c’est un parti de primates. Il est hors de question de discuter avec des primates. Claude Goasguen (UMP, Paris, 2011)

Ne laissez pas la grande primate de l’extrême goitre prendre le mouchoir … François Morel (France inter)

Pendant toutes les années du mitterrandisme, nous n’avons jamais été face à une menace fasciste, donc tout antifascisme n’était que du théâtre. Nous avons été face à un parti, le Front National, qui était un parti d’extrême droite, un parti populiste aussi, à sa façon, mais nous n’avons jamais été dans une situation de menace fasciste, et même pas face à un parti fasciste. D’abord le procès en fascisme à l’égard de Nicolas Sarkozy est à la fois absurde et scandaleux. Je suis profondément attaché à l’identité nationale et je crois même ressentir et savoir ce qu’elle est, en tout cas pour moi. L’identité nationale, c’est notre bien commun, c’est une langue, c’est une histoire, c’est une mémoire, ce qui n’est pas exactement la même chose, c’est une culture, c’est-à-dire une littérature, des arts, la philo, les philosophies. Et puis, c’est une organisation politique avec ses principes et ses lois. Quand on vit en France, j’ajouterai : l’identité nationale, c’est aussi un art de vivre, peut-être, que cette identité nationale. Je crois profondément que les nations existent, existent encore, et en France, ce qui est frappant, c’est que nous sommes à la fois attachés à la multiplicité des expressions qui font notre nation, et à la singularité de notre propre nation. Et donc ce que je me dis, c’est que s’il y a aujourd’hui une crise de l’identité, crise de l’identité à travers notamment des institutions qui l’exprimaient, la représentaient, c’est peut-être parce qu’il y a une crise de la tradition, une crise de la transmission. Il faut que nous rappelions les éléments essentiels de notre identité nationale parce que si nous doutons de notre identité nationale, nous aurons évidemment beaucoup plus de mal à intégrer. Lionel Jospin (France Culture, 29.09.07)

You often hear men say, “Why don’t they just leave?” [. . .] And I ask them, how many of you seen the movie Deliverance? And every man will raise his hand. And I’ll say, what’s the one scene you remember in Deliverance? And every man here knows exactly what scene to think of. And I’ll say, “After those guys tied that one guy in that tree and raped him, man raped him, in that film. Why didn’t the guy go to the sheriff? What would you have done? “Well, I’d go back home get my gun. I’d come back and find him.” Why wouldn’t you go to the sheriff? Why? Well, the reason why is they are ashamed. They are embarrassed. I say, why do you think so many women that get raped, so many don’t report it? They don’t want to get raped again by the system. Joe Biden

Trump’s message resonates with working class stiffs who believe that, despite his wealth, he understands them and their concerns. When he speaks, they understand him. There’s no complex grammar to parse. And there’s none of the phony folksiness you get from the Dems, none of the sho-nuffs and y’alls from a Hillary. To many ordinary Americans, Trump represents the promise of America as a land where everyone should have an opportunity to make it to the top if he works hard enough. These are the folks who gave the last election to Barak Obama because he made this promise, and now they’re disillusioned. (…) Many Ruling Class Republicans seem to suffer from Trump Derangement Syndrome. To these folks, the Trump-Kelly dust-up was the last straw. Writing in the Post, Jennifer Rubin bellyaches that Trump “whines,” “bellyaches,” and “complains.” Even (gasp!) “during the debate.” Trump had the unmitigated chutzpah to call out a member of the sacred media priesthood when she was behaving unprofessionally towards him. Genteel Republicans don’t do that. As is his wont, Trump readily admits the obvious. “I’m the most fabulous whiner…. and I keep whining and whining until I win.” And win he did, Most candidates beg the media to cover them. The reverse is true with Trump. After the dust-up with Kelly, it was Trump who black-listed Fox when he was doing the Sunday news shows, and Fox begged him to come back and make up. Wanna bet that in the future a debate moderator will think twice before treating Trump unfairly? (…) George Will is not the only Ruling Class Republican to express contempt for Donald Trump. And some express even more contempt for those who like him. Writing for National Review Online, Charles C. Cooke calls Trump a “virus.” (What is it with these misophobics?) and those who like him are ill, infected. You can recognize them because “by their dull, unreflective, often ovine behavior, they resemble binary and nuanceless drones.” Nuanceless? Choosing Trump for the presidential nomination, explains Cooke, is “comparable…to a person’s choosing a disabled man to run in a marathon.” Who would do something like that? Oh, wait. The disabled do compete in marathons, and have done so with pride since 1972. I’m sure that Cooke didn’t intend to diss the disabled. The problem for Ruling Class Conservatives like Will and Cooke, is that the Left has emasculated them. They tremble lest they let slip a faux pas that the Left can jump upon. They must at all times show that their Conservatism is “intellectually respectable and politically palatable,” and worry that Trump will make them look bad to the Liberals and their media. They are unable to grasp the fact that, notwithstanding all their efforts, the Left will never regard them as respectable and palatable. To achieve that goal, they must first become Liberals themselves. Trump makes it clear that he doesn’t give a damn what Liberals think of us. And everyday people of all political persuasions applaud when he stands up to the self-important elitist media, just as they did with Newt Gingrich in 2012. It’s time for the Right to man-up. Emulate Donald Trump and the Canadians. Esther Goldberg

After the election, in liberal, urban America, one often heard Trump’s win described as the revenge of the yahoos in flyover country, fueled by their angry “isms” and “ias”: racism, anti-Semitism, nativism, homophobia, Islamophobia, and so on. Many liberals consoled themselves that Trump’s victory was the last hurrah of bigoted, Republican white America, soon to be swept away by vast forces beyond its control, such as global migration and the cultural transformation of America into something far from the Founders’ vision. As insurance, though, furious progressives also renewed calls to abolish the Electoral College, advocating for a constitutional amendment that would turn presidential elections into national plebiscites. Direct presidential voting would shift power to heavily urbanized areas—why waste time trying to reach more dispersed voters in less populated rural states?—and thus institutionalize the greater economic and cultural clout of the metropolitan blue-chip universities, the big banks, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, New York–Washington media, and Hollywood, Democrat-voting all. Barack Obama’s two electoral victories deluded the Democrats into thinking that it was politically wise to jettison their old blue-collar appeal to the working classes, mostly living outside the cities these days, in favor of an identity politics of a new multicultural, urban America. Yet Trump’s success represented more than simply a triumph of rural whites over multiracial urbanites. More ominously for liberals, it also suggested that a growing minority of blacks and Hispanics might be sympathetic with a “country” mind-set that rejects urban progressive elitism. For some minorities, sincerity and directness might be preferable to sloganeering by wealthy white urban progressives, who often seem more worried about assuaging their own guilt than about genuinely understanding people of different colors. Trump’s election underscored two other liberal miscalculations. First, Obama’s progressive agenda and cultural elitism prevailed not because of their ideological merits, as liberals believed, but because of his great appeal to urban minorities in 2008 and 2012, who voted in solidarity for the youthful first African-American president in numbers never seen before. That fealty wasn’t automatically transferable to liberal white candidates, including the multimillionaire 69-year-old Hillary Clinton. Obama had previously lost most of America’s red counties, but not by enough to keep him from winning two presidential elections, with sizable urban populations in Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania turning out to vote for the most left-wing presidential candidate since George McGovern. Second, rural America hadn’t fully raised its electoral head in anger in 2008 and 2012 because it didn’t see the Republican antidotes to Obama’s progressive internationalism as much better than the original malady. Socially moderate establishmentarians like the open-borders-supporting John McCain or wealthy businessman Mitt Romney didn’t resonate with the spirit of rural America—at least not enough to persuade millions to come to the polls instead of sitting the elections out. Trump connected with these rural voters with far greater success than liberals anticipated. Urban minorities failed in 2016 to vote en bloc, in their Obama-level numbers; and rural Americans, enthused by Trump, increased their turnout, so that even a shrinking American countryside still had enough clout to win. What is insufficiently understood is why a hurting rural America favored the urban, superrich Trump in 2016 and, more generally, tends to vote more conservative than liberal. Ostensibly, the answer is clear: an embittered red-state America has found itself left behind by elite-driven globalization, battered by unfettered trade and high-tech dislocations in the economy. In some of the most despairing counties, rural life has become a mirror image of the inner city, ravaged by drug use, criminality, and hopelessness. Yet if muscular work has seen a decline in its relative monetary worth, it has not necessarily lost its importance. After all, the elite in Washington and Menlo Park appreciate the fresh grapes and arugula that they purchase at Whole Foods. Someone mined the granite used in their expensive kitchen counters and cut the timber for their hardwood floors. The fuel in their hybrid cars continues to come from refined oil. The city remains as dependent on this elemental stuff—typically produced outside the suburbs and cities—as it always was. The two Palo Altoans at Starbucks might have forgotten that their overpriced homes included two-by-fours, circuit breakers, and four-inch sewer pipes, but somebody somewhere made those things and brought them into their world. In the twenty-first century, though, the exploitation of natural resources and the manufacturing of products are more easily outsourced than are the arts of finance, insurance, investments, higher education, entertainment, popular culture, and high technology, immaterial sectors typically pursued within metropolitan contexts and supercharged by the demands of increasingly affluent global consumers. A vast government sector, mostly urban, is likewise largely impervious to the leveling effects of a globalized economy, even as its exorbitant cost and extended regulatory reach make the outsourcing of material production more likely. Asian steel may have devastated Youngstown, but Chinese dumping had no immediate effect on the flourishing government enclaves in Washington, Maryland, and Virginia, filled with well-paid knowledge workers. Globalization, big government, and metastasizing regulations have enriched the American coasts, in other words, while damaging much of the nation’s interior. Few major political leaders before Trump seemed to care. He hammered home the point that elites rarely experienced the negative consequences of their own ideologies. New York Times columnists celebrating a “flat” world have yet to find themselves flattened by Chinese writers willing to write for a fraction of their per-word rate. Tenured Harvard professors hymning praise to global progressive culture don’t suddenly discover their positions drawn and quartered into four part-time lecturer positions. And senators and bureaucrats in Washington face no risk of having their roles usurped by low-wage Vietnamese politicians. Trump quickly discovered that millions of Americans were irate that the costs and benefits of our new economic reality were so unevenly distributed. As the nation became more urban and its wealth soared, the old Democratic commitment from the Roosevelt era to much of rural America—construction of water projects, rail, highways, land banks, and universities; deference to traditional values; and Grapes of Wrath–like empathy—has largely been forgotten. A confident, upbeat urban America promoted its ever more radical culture without worrying much about its effects on a mostly distant and silent small-town other. In 2008, gay marriage and women in combat were opposed, at least rhetorically, by both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton in their respective presidential campaigns. By 2016, mere skepticism on these issues was viewed by urban elites as reactionary ignorance. In other words, it was bad enough that rural America was getting left behind economically; adding insult to injury, elite America (which is Democrat America) openly caricatured rural citizens’ traditional views and tried to force its own values on them. Lena Dunham’s loud sexual politics and Beyoncé’s uncritical evocation of the Black Panthers resonated in blue cities and on the coasts, not in the heartland. Only in today’s bifurcated America could billion-dollar sports conglomerates fail to sense that second-string San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s protests of the national anthem would turn off a sizable percentage of the National Football League’s viewing audience, which is disproportionately conservative and middle American. These cultural themes, too, Trump addressed forcefully. In classical literature, patriotism and civic militarism were always closely linked with farming and country life. In the twenty-first century, this is still true. The incubator of the U.S. officer corps is red-state America. “Make America Great Again” reverberated in the pro-military countryside because it emphasized an exceptionalism at odds with the Left’s embrace of global values. Residents in Indiana and Wisconsin were unimpressed with the Democrats’ growing embrace of European-style “soft power,” socialism, and statism—all the more so in an age of European constitutional, financial, and immigration sclerosis. Trump’s slogan unabashedly expressed American individualism; Clinton’s “Stronger Together” gave off a whiff of European socialist solidarity. Trump, the billionaire Manhattanite wheeler-dealer, made an unlikely agrarian, true; but he came across during his presidential run as a clear advocate of old-style material jobs, praising vocational training and clearly enjoying his encounters with middle-American homemakers, welders, and carpenters. Trump talked more on the campaign about those who built his hotels than those who financed them. He could point to the fact that he made stuff, unlike Clinton, who got rich without any obvious profession other than leveraging her office. Give the thrice-married, orange-tanned, and dyed-haired Trump credit for his political savvy in promising to restore to the dispossessed of the Rust Belt their old jobs and to give back to farmers their diverted irrigation water, and for assuring small towns that arriving new Americans henceforth would be legal—and that, over time, they would become similar to their hosts in language, custom, and behavior. Ironically, part of Trump’s attraction for red-state America was his posture as a coastal-elite insider—but now enlisted on the side of the rustics. A guy who had built hotels all over the world, and understood how much money was made and lost through foreign investment, offered to put such expertise in the service of the heartland—against the supposed currency devaluers, trade cheats, and freeloaders of Europe, China, and Japan. Trump’s appeal to the interior had partly to do with his politically incorrect forthrightness. Each time Trump supposedly blundered in attacking a sacred cow—sloppily deprecating national hero John McCain’s wartime captivity or nastily attacking Fox superstar Megyn Kelly for her supposed unfairness—the coastal media wrote him off as a vulgar loser. Not Trump’s base. Seventy-five percent of his supporters polled that his crude pronouncements didn’t bother them. As one grape farmer told me after the Access Hollywood hot-mike recordings of Trump making sexually vulgar remarks had come to light, “Who cares? I’d take Trump on his worst day better than Hillary on her best.” Apparently red-state America was so sick of empty word-mongering that it appreciated Trump’s candor, even when it was sometimes inaccurate, crude, or cruel. Outside California and New York City and other elite blue areas, for example, foreigners who sneak into the country and reside here illegally are still “illegal aliens,” not “undocumented migrants,” a blue-state term that masks the truth of their actions. Trump’s Queens accent and frequent use of superlatives—“tremendous,” “fantastic,” “awesome”—weren’t viewed by red-state America as a sign of an impoverished vocabulary but proof that a few blunt words can capture reality. To the rural mind, verbal gymnastics reveal dishonest politicians, biased journalists, and conniving bureaucrats, who must hide what they really do and who they really are. Think of the arrogant condescension of Jonathan Gruber, one of the architects of the disastrous Obamacare law, who admitted that the bill was written deliberately in a “tortured way” to mislead the “stupid” American voter. To paraphrase Cicero on his preference for the direct Plato over the obscure Pythagoreans, rural Americans would have preferred to be wrong with the blunt-talking Trump than to be right with the mush-mouthed Hillary Clinton. One reason that Trump may have outperformed both McCain and Romney with minority voters was that they appreciated how much the way he spoke rankled condescending white urban liberals. Poorer, less cosmopolitan, rural people can also experience a sense of inferiority when they venture into the city, unlike smug urbanites visiting red-state America. The rural folk expect to be seen as deplorables, irredeemables, and clingers by city folk. My countryside neighbors do not wish to hear anything about Stanford University, where I work—except if by chance I note that Stanford people tend to be condescending and pompous, confirming my neighbors’ suspicions about city dwellers. And just as the urban poor have always had their tribunes, so, too, have rural residents flocked to an Andrew Jackson or a William Jennings Bryan, politicians who enjoyed getting back at the urban classes for perceived slights. The more Trump drew the hatred of PBS, NPR, ABC, NBC, CBS, the elite press, the universities, the foundations, and Hollywood, the more he triumphed in red-state America. Indeed, one irony of the 2016 election is that identity politics became a lethal boomerang for progressives. After years of seeing America reduced to a binary universe, with culpable white Christian males encircled by ascendant noble minorities, gays, feminists, and atheists—usually led by courageous white-male progressive crusaders—red-state America decided that two could play the identity-politics game. In 2016, rural folk did silently in the voting booth what urban America had done to them so publicly in countless sitcoms, movies, and political campaigns. In sum, Donald Trump captured the twenty-first-century malaise of a rural America left behind by globalized coastal elites and largely ignored by the establishments of both political parties. Central to Trump’s electoral success, too, were age-old rural habits and values that tend to make the interior broadly conservative. That a New York billionaire almost alone grasped how red-state America truly thought, talked, and acted, and adjusted his message and style accordingly, will remain one of the astonishing ironies of American political history. Victor Davis Hanson

Né à Detroit dans les années 1950, j’ai grandi dans une famille où personne n’avait fréquenté l’université. Lorsque j’ai obtenu une bourse pour l’université du Michigan, j’ai été confronté à un snobisme de gauche qui méprisait la classe ouvrière, son attachement à la famille, la religion. Cette gauche caviar a suscité chez moi une forte réaction. Mark Lilla

Une des nombreuses leçons à tirer de la présidentielle américaine et de son résultat détestable, c’est qu’il faut clore l’ère de la gauche « diversitaire ». Hillary Clinton n’a jamais été aussi excellente et stimulante que lorsqu’elle évoquait l’engagement des États-Unis dans les affaires du monde et en quoi il est lié à notre conception de la démocratie. En revanche, dès qu’il s’agissait de politique intérieure, elle n’avait plus la même hauteur de vue et tendait à verser dans le discours de la diversité, en en appelant explicitement à l’électorat noir, latino, féminin et LGBT (lesbiennes, gays, bisexuels et trans). Elle a commis là une erreur stratégique. Tant qu’à mentionner des groupes aux États-Unis, mieux vaut les mentionner tous. Autrement, ceux que l’on a oubliés s’en aperçoivent et se sentent exclus. C’est exactement ce qui s’est passé avec les Blancs des classes populaires et les personnes à fortes convictions religieuses. Pas moins des deux tiers des électeurs blancs non diplômés du supérieur ont voté pour Donald Trump, de même que plus de 80 % des évangéliques blancs. (…) l’obsession de la diversité à l’école et dans la presse a produit à gauche une génération de narcissiques, ignorant le sort des personnes n’appartenant pas aux groupes auxquels ils s’identifient, et indifférents à la nécessité d’être à l’écoute des Américains de toutes conditions. Dès leur plus jeune âge, nos enfants sont incités à parler de leur identité individuelle, avant même d’en avoir une. Au moment où ils entrent à l’université, beaucoup pensent que le discours politique se réduit au discours de la diversité, et on est consterné de voir qu’ils n’ont pas d’avis sur des questions aussi éternelles que les classes sociales, la guerre, l’économie et le bien commun. L’enseignement de l’histoire dans les écoles secondaires en est grandement responsable, car les programmes adoptés plaquent sur le passé le discours actuel de l’identité et donnent une vision déformée des grandes forces et des grands personnages qui ont façonné notre pays (les conquêtes du mouvement pour les droits des femmes, par exemple, sont réelles et importantes, mais on ne peut les comprendre qu’à la lumière des accomplissements des Pères fondateurs, qui ont établi un système de gouvernement fondé sur la garantie des droits). Quand les jeunes entrent à l’université, ils sont incités à rester centrés sur eux-mêmes par les associations étudiantes, par les professeurs ainsi que par les membres de l’administration qui sont employés à plein temps pour gérer les « questions de diversité » et leur donner encore plus d’importance. La chaîne Fox News et d’autres médias de droite adorent railler la « folie des campus » autour de ces questions, et il y a le plus souvent de quoi. Cela fait le jeu des démagogues populistes qui cherchent à délégitimer le savoir aux yeux de ceux qui n’ont jamais mis les pieds sur un campus. Comment expliquer à l’électeur moyen qu’il y a censément urgence morale à accorder aux étudiants le droit de choisir le pronom personnel par lequel ils veulent être désignés ? Comment ne pas rigoler avec ces électeurs quand on apprend qu’un farceur de l’université du Michigan a demandé à se faire appeler « Sa majesté » ? Cette sensibilité à la diversité sur les campus a déteint sur les médias de gauche, et pas qu’un peu. L’embauche de femmes et de membres des minorités au titre de la discrimination positive dans la presse écrite et l’audiovisuel est une formidable avancée sociale – et cela a même transformé le visage des médias de droite. Mais cela a aussi contribué à donner le sentiment, surtout aux jeunes journalistes et rédacteurs en chef, qu’en traitant de l’identité ils avaient accompli leur travail. (…) Combien de fois, par exemple, nous ressert-on le sujet sur le « premier ou la première X à faire Y » ? La fascination pour les questions d’identité se retrouve même dans la couverture de l’actualité internationale qui est, hélas, une denrée rare. Il peut être intéressant de lire un article sur le sort des personnes transgenre en Égypte, par exemple, mais cela ne contribue en rien à informer les Américains sur les puissants courants politiques et religieux qui détermineront l’avenir de l’Égypte et, indirectement, celui de notre pays. (…) Mais c’est au niveau de la stratégie électorale que l’échec de la gauche diversitaire a été le plus spectaculaire, comme nous venons de le constater. En temps normal, la politique nationale n’est pas axée sur ce qui nous différencie mais sur ce qui nous unit. Et nous choisissons pour la conduire la personne qui aura le mieux su nous parler de notre destin collectif. Ronald Reagan a été habile à cela, quoiqu’on pense de sa vision. Bill Clinton aussi, qui a pris exemple sur Reagan. Il s’est emparé du Parti démocrate en marginalisant son aile sensible aux questions d’identité, a concentré son énergie sur des mesures de politique intérieure susceptibles de bénéficier à l’ensemble de la population (comme l’assurance-maladie) et défini le rôle des États-Unis dans le monde d’après la chute du mur de Berlin. En poste pour deux mandats, il a ainsi été en mesure d’en faire beaucoup pour différentes catégories d’électeurs membres de la coalition démocrate. La politique de la différence est essentiellement expressive et non persuasive. Voilà pourquoi elle ne fait jamais gagner des élections – mais peut en faire perdre. L’intérêt récent, quasi ethnologique, des médias pour l’homme blanc en colère en dit autant sur l’état de la gauche américaine que sur cette figure tant vilipendée et, jusqu’ici, dédaignée. Pour la gauche, une lecture commode de la récente élection présidentielle consisterait à dire que Donald Trump a gagné parce qu’il a réussi à transformer un désavantage économique en colère raciste – c’est la thèse du whitelash, du retour de bâton de l’électorat blanc. C’est une lecture commode parce qu’elle conforte un sentiment de supériorité morale et permet à la gauche de faire la sourde oreille à ce que ces électeurs ont dit être leur principale préoccupation. Cette lecture alimente aussi le fantasme selon lequel la droite républicaine serait condamnée à terme à l’extinction démographique – autrement dit, que la gauche n’a qu’à attendre que le pays lui tombe tout cuit dans l’assiette. Le pourcentage étonnamment élevé du vote latino qui est allé à M. Trump est là pour nous rappeler que plus des groupes ethniques sont établis depuis longtemps aux États-Unis, moins leur comportement électoral est homogène. Enfin, la thèse du whitelash est commode parce qu’elle disculpe la gauche de ne pas avoir vu que son obsession de la diversité incitait les Américains blancs, ruraux, croyants, à se concevoir comme un groupe défavorisé dont l’identité est menacée ou bafouée. Ces personnes ne réagissent pas contre la réalité d’une Amérique multiculturelle (en réalité, elles ont tendance à vivre dans des régions où la population est homogène). Elles réagissent contre l’omniprésence du discours de l’identité, ce qu’elles appellent le « politiquement correct ». La gauche ferait bien de garder à l’esprit que le Ku Klux Klan est le plus ancien mouvement identitaire de la vie politique américaine, et qu’il existe toujours. Quand on joue au jeu de l’identité, il faut s’attendre à perdre. Il nous faut une gauche postdiversitaire, qui s’inspire des succès passés de la gauche prédiversitaire. Cette gauche-là s’attacherait à élargir sa base en s’adressant aux Américains en leur qualité d’Américains et en privilégiant les questions qui concernent une vaste majorité d’entre eux. Elle parlerait à la nation en tant que nation de citoyens qui sont tous dans le même bateau et doivent se serrer les coudes. Pour ce qui est des questions plus étroites et symboliquement très chargées qui risquent de faire fuir des électeurs potentiels, notamment celles qui touchent à la sexualité et à la religion, cette gauche-là procéderait doucement, avec tact et sens de la mesure. Les enseignants acquis à cette gauche-là se recentreraient sur la principale responsabilité politique qui est la leur dans une démocratie : former des citoyens engagés qui connaissent leur système politique ainsi que les grandes forces et les principaux événements de leur histoire. Cette gauche postdiversitaire rappellerait également que la démocratie n’est pas qu’une affaire de droits ; elle confère aussi des devoirs à ses citoyens, par exemple le devoir de s’informer et celui de voter. Une presse de gauche postdiversitaire commencerait par s’informer sur les régions du pays dont elle a fait peu de cas, et sur les questions qui les préoccupent, notamment la religion. Et elle s’acquitterait avec sérieux de sa responsabilité d’informer les Américains sur les grandes forces qui régissent les relations internationales. J’ai été invité il y a quelques années à un congrès syndical en Floride pour parler du célèbre discours du président Franklin D. Roosevelt de 1941 sur les quatre libertés. La salle était bondée de représentants de sections locales – hommes, femmes, Noirs, Blanc, Latinos. Nous avons commencé par chanter l’hymne national puis nous nous sommes assis pour écouter un enregistrement du discours de Roosevelt. J’observais la diversité des visages dans l’assistance et j’étais frappé de voir à quel point ces personnes si différentes étaient concentrées sur ce qui les rassemblait. Et, en entendant Roosevelt invoquer d’une voix vibrante la liberté d’expression, la liberté de culte, la liberté de vivre à l’abri du besoin et la liberté de vivre à l’abri de la peur – des libertés qu’il réclamait « partout dans le monde » – cela m’a rappelé quels étaient les vrais fondements de la gauche américaine moderne. Mark Lilla

Dix jours à peine après l’élection de Trump, Lilla publie une tribune dans le New York Times, où il étrille la célébration univoque de la diversité par l’élite intellectuelle progressiste comme principale cause de sa défaite face à Trump. «Ces dernières années, la gauche américaine a cédé, à propos des identités ethniques, de genre et de sexualité, à une sorte d’hystérie collective qui a faussé son message au point de l’empêcher de devenir une force fédératrice capable de gouverner […], estime-t-il. Une des nombreuses leçons à tirer de la présidentielle américaine et de son résultat détestable, c’est qu’il faut clore l’ère de la gauche diversitaire.» De cette diatribe à succès, l’universitaire a fait un livre tout aussi polémique, The Once and Future Liberal. After Identity Politics, dont la traduction française vient d’être publiée sous le titre la Gauche identitaire. L’Amérique en miettes (Stock). Un ouvrage provocateur destiné à sonner l’alerte contre le «tournant identitaire» pris par le Parti démocrate sous l’influence des «idéologues de campus», «ces militants qui ne savent plus parler que de leur différence.» «Une vision politique large a été remplacée par une pseudo-politique et une rhétorique typiquement américaine du moi sensible qui lutte pour être reconnu», développe Lilla. Dans son viseur : les mouvements féministes, gays, indigènes ou afro comme Black Lives Matter («le meilleur moyen de ne pas construire de solidarité»). Bref, tout ce qui est minoritaire et qui s’exprime à coups d’occupation de places publiques, de pétitions et de tribunes dans les journaux est fautif à ses yeux d’avoir fragmenté la gauche américaine. L’essayiste situe l’origine de cette «dérive» idéologique au début des années 70, lorsque la Nouvelle Gauche interprète «à l’envers» la formule «le privé est politique», considérant que tout acte politique n’est rien d’autre qu’une activité personnelle. Ce «culte de l’identité» et des «particularismes» issus de la révolution culturelle et morale des Sixties a convergé avec les révolutions économiques sous l’ère Reagan pour devenir «l’idéologie dominante.» «La politique identitaire, c’est du reaganisme pour gauchiste», résume cet adepte de la «punchline» idéologico-politique. Intellectuel au profil hybride, combattant à la fois la pensée conservatrice et la pensée progressiste, Lilla agace plus à gauche qu’à droite où sa dénonciation de «l’idéologie de la diversité», de «ses limites» et «ses dangers» est perçue comme l’expression ultime d’un identitarisme masculin blanc. Positionnement transgressif qu’on ferait volontiers graviter du côté de la «nouvelle réaction», ce qu’il réfute. (…) L’essai de Lilla peut se lire comme un avertissement lancé à la gauche intellectuelle française, aujourd’hui divisée entre «républicanistes» et « décoloniaux ». Libération

Notre situation est parfaitement paradoxale. Jamais les ennemis de l’Union européenne n’ont eu à ce point le sentiment de toucher au but, de presque en voir la fin, et cependant jamais, je le crois, les peuples d’Europe n’ont été plus sérieusement, plus gravement attachés à l’Union. Quel malentendu! Voilà bien l’un des plus fâcheux résultats de notre incapacité à discuter, de notre nouvelle inclination pour la simplification à outrance des points de vue. L’hypothèse d’un repli nationaliste procède d’une erreur d’interprétation. Il n’y a pas de demande de repli nationaliste, mais une demande de protection, de régulation politique, de contrôle du cours des choses. C’est une demande de puissance publique qui ne heurte pas l’idée européenne. C’est en refusant de répondre à cette demande éminemment légitime et recevable que l’Union finira par conduire les Européens à revenir, la mort dans l’âme, au dogme nationaliste. (…) Trump marque le retour d’une figure classique mais oubliée chez nous, celle de l’homme d’État qui n’a d’intérêt que pour son pays. Il assume une politique de puissance. (…) [ souligner le clivage avec l’Europe de l’Est] C’est un risque politique, sur le plan national comme sur le plan européen. (…) La double défaite signifierait a posteriori l’imprudence du pari et pèserait sur les deux niveaux, européen et national en affaiblissant dangereusement le président. (…) Du côté des gouvernements, cessons de surjouer l’opposition frontale. (…) nous devons accepter cet attachement viscéral des Européens à leur patrimoine immatériel, leur manière de vivre, leur souveraineté, parfois si récente ou retrouvée depuis si peu et si chèrement payée. Dominique Reynié

Ce qui est nouveau, c’est d’abord que la bourgeoisie a le visage de l’ouverture et de la bienveillance. Elle a trouvé un truc génial : plutôt que de parler de « loi du marché », elle dit « société ouverte », « ouverture à l’Autre » et liberté de choisir… Les Rougon-Macquart sont déguisés en hipsters. Ils sont tous très cools, ils aiment l’Autre. Mieux : ils ne cessent de critiquer le système, « la finance », les « paradis fiscaux ». On appelle cela la rebellocratie. C’est un discours imparable : on ne peut pas s’opposer à des gens bienveillants et ouverts aux autres ! Mais derrière cette posture, il y a le brouillage de classes, et la fin de la classe moyenne. La classe moyenne telle qu’on l’a connue, celle des Trente Glorieuses, qui a profité de l’intégration économique, d’une ascension sociale conjuguée à une intégration politique et culturelle, n’existe plus même si, pour des raisons politiques, culturelles et anthropologiques, on continue de la faire vivre par le discours et les représentations. (…) C’est aussi une conséquence de la non-intégration économique. Aujourd’hui, quand on regarde les chiffres – notamment le dernier rapport sur les inégalités territoriales publié en juillet dernier –, on constate une hyper-concentration de l’emploi dans les grands centres urbains et une désertification de ce même emploi partout ailleurs. Et cette tendance ne cesse de s’accélérer ! Or, face à cette situation, ce même rapport préconise seulement de continuer vers encore plus de métropolisation et de mondialisation pour permettre un peu de redistribution. Aujourd’hui, et c’est une grande nouveauté, il y a une majorité qui, sans être « pauvre » ni faire les poubelles, n’est plus intégrée à la machine économique et ne vit plus là où se crée la richesse. Notre système économique nécessite essentiellement des cadres et n’a donc plus besoin de ces millions d’ouvriers, d’employés et de paysans. La mondialisation aboutit à une division internationale du travail : cadres, ingénieurs et bac+5 dans les pays du Nord, ouvriers, contremaîtres et employés là où le coût du travail est moindre. La mondialisation s’est donc faite sur le dos des anciennes classes moyennes, sans qu’on le leur dise ! Ces catégories sociales sont éjectées du marché du travail et éloignées des poumons économiques. Cependant, cette« France périphérique » représente quand même 60 % de la population. (…) Ce phénomène présent en France, en Europe et aux États-Unis a des répercussions politiques : les scores du FN se gonflent à mesure que la classe moyenne décroît car il est aujourd’hui le parti de ces « superflus invisibles » déclassés de l’ancienne classe moyenne. (…) Toucher 100 % d’un groupe ou d’un territoire est impossible. Mais j’insiste sur le fait que les classes populaires (jeunes, actifs, retraités) restent majoritaires en France. La France périphérique, c’est 60 % de la population. Elle ne se résume pas aux zones rurales identifiées par l’Insee, qui représentent 20 %. Je décris un continuum entre les habitants des petites villes et des zones rurales qui vivent avec en moyenne au maximum le revenu médian et n’arrivent pas à boucler leurs fins de mois. Face à eux, et sans eux, dans les quinze plus grandes aires urbaines, le système marche parfaitement. Le marché de l’emploi y est désormais polarisé. Dans les grandes métropoles il faut d’une part beaucoup de cadres, de travailleurs très qualifiés, et de l’autre des immigrés pour les emplois subalternes dans le BTP, la restauration ou le ménage. Ainsi les immigrés permettent-ils à la nouvelle bourgeoisie de maintenir son niveau de vie en ayant une nounou et des restaurants pas trop chers. (…) Il n’y a aucun complot mais le fait, logique, que la classe supérieure soutient un système dont elle bénéficie – c’est ça, la « main invisible du marché» ! Et aujourd’hui, elle a un nom plus sympathique : la « société ouverte ». Mais je ne pense pas qu’aux bobos. Globalement, on trouve dans les métropoles tous ceux qui profitent de la mondialisation, qu’ils votent Mélenchon ou Juppé ! D’ailleurs, la gauche votera Juppé. C’est pour cela que je ne parle ni de gauche, ni de droite, ni d’élites, mais de « la France d’en haut », de tous ceux qui bénéficient peu ou prou du système et y sont intégrés, ainsi que des gens aux statuts protégés : les cadres de la fonction publique ou les retraités aisés. Tout ce monde fait un bloc d’environ 30 ou 35 %, qui vit là où la richesse se crée. Et c’est la raison pour laquelle le système tient si bien. (…) La France périphérique connaît une phase de sédentarisation. Aujourd’hui, la majorité des Français vivent dans le département où ils sont nés, dans les territoires de la France périphérique il s’agit de plus de 60 % de la population. C’est pourquoi quand une usine ferme – comme Alstom à Belfort –, une espèce de rage désespérée s’empare des habitants. Les gens deviennent dingues parce qu’ils savent que pour eux « il n’y a pas d’alternative » ! Le discours libéral répond : « Il n’y a qu’à bouger ! » Mais pour aller où ? Vous allez vendre votre baraque et déménager à Paris ou à Bordeaux quand vous êtes licencié par ArcelorMittal ou par les abattoirs Gad ? Avec quel argent ? Des logiques foncières, sociales, culturelles et économiques se superposent pour rendre cette mobilité quasi impossible. Et on le voit : autrefois, les vieux restaient ou revenaient au village pour leur retraite. Aujourd’hui, la pyramide des âges de la France périphérique se normalise. Jeunes, actifs, retraités, tous sont logés à la même enseigne. La mobilité pour tous est un mythe. Les jeunes qui bougent, vont dans les métropoles et à l’étranger sont en majorité issus des couches supérieures. Pour les autres ce sera la sédentarisation. Autrefois, les emplois publics permettaient de maintenir un semblant d’équilibre économique et proposaient quelques débouchés aux populations. Seulement, en plus de la mondialisation et donc de la désindustrialisation, ces territoires ont subi la retraite de l’État. (…) Même si l’on installe 20 % de logements sociaux partout dans les grandes métropoles, cela reste une goutte d’eau par rapport au parc privé « social de fait » qui existait à une époque. Les ouvriers, autrefois, n’habitaient pas dans des bâtiments sociaux, mais dans de petits logements, ils étaient locataires, voire propriétaires, dans le parc privé à Paris ou à Lyon. C’est le marché qui crée les conditions de la présence des gens et non pas le logement social. Aujourd’hui, ce parc privé « social de fait » s’est gentrifié et accueille des catégories supérieures. Quant au parc social, il est devenu la piste d’atterrissage des flux migratoires. Si l’on regarde la carte de l’immigration, la dynamique principale se situe dans le Grand Ouest, et ce n’est pas dans les villages que les immigrés s’installent, mais dans les quartiers de logements sociaux de Rennes, de Brest ou de Nantes. (…) In fine, il y a aussi un rejet du multiculturalisme. Les gens n’ont pas envie d’aller vivre dans les derniers territoires des grandes villes ouverts aux catégories populaires : les banlieues et les quartiers à logements sociaux qui accueillent et concentrent les flux migratoires. Christophe Guilluy

La société ouverte (…), c’est la grande fake news de la mondialisation. Quand on regarde les choses de près, les gens qui vendent le plus la société ouverte sont ceux qui vivent dans le plus grand grégarisme social, ceux qui contournent le plus la carte scolaire, ceux qui vivent dans l’entre-soi et qui font des choix résidentiels qui leur permettent à la fin de tenir le discours de la société ouverte puisque de toute façon, ils ont, eux, les moyens de la frontière invisible. Et précisément, ce qui est à l’inverse la situation des catégories modestes, c’est qu’elles n’ont pas les moyens de la frontière invisible. Ca n’en fait pas des xénophobes ou des gens qui sont absolument contre l’autre. Ca fait simplement des gens qui veulent qu’un Etat régule. Christophe Guilluy

Que nous dit Christophe Guilluy ? Que la scission est aujourd’hui consommée entre une élite déconnectée et une classe populaire précarisée. Et que la classe moyenne, qu’il définit comme « une classe majoritaire dans laquelle tout le monde était intégré, de l’ouvrier au cadre », est un champ de ruines. Ce dernier point est affirmé, répété, martelé, « implosion d’un modèle qui n’intègre plus les classes populaires, qui constituaient, hier, le socle de la classe moyenne occidentale et en portait les valeurs ». Dès lors, les groupes sociaux en présence « ne font plus société ». C’est là le sens du titre, « No Society », reprise qui n’a rien d’innocente d’un aphorisme de feu la Première ministre britannique Margaret Thatcher – déjà responsable du célèbre Tina, « There is no alternative » –, dont la politique néolibérale agressive, véritable plan de casse sociale dans les années 1980, définit toujours le modèle outre-Manche. Guilluy se fait lanceur d’alerte. Il constate, à l’instar de l’économiste Thomas Piketty, dont il cite les travaux à plusieurs reprises, le fossé toujours plus large qui sépare les catégories les plus aisées, des classes défavorisées. Une situation qui induit une nouvelle géographie sociale et politique. Et explique, selon lui, l’insécurité culturelle s’ajoutant à l’insécurité sociale, la vague populiste qui balaie la France, la Grande-Bretagne, l’Italie, l’Allemagne, les États-Unis et aujourd’hui le Brésil. Pour l’auteur, comme pour d’autres analystes, l’élection de Trump n’est pas un accident, mais l’aboutissement d’un processus que les élites, drapées dans « un mépris de classe », auraient voulu renvoyer aux marges. Ce qui fâche politiques, chefs d’entreprise et médias ? Cette propension à mettre tout le monde dans le même sac, tous complices de défendre, « au nom du bien commun », une idéologie néolibérale jugée destructrice. Et de masquer les vrais problèmes à l’aide d’éléments de langage. Guilluy conspue les 0,1 %, ces superpuissances économiques, tentées par l’anarcho-capitalisme, qui siphonnent les richesses mondiales. Tout comme il rejette la métropolisation des territoires, encouragée par l’Europe, qui tend à concentrer les créations d’emplois dans les zones urbaines, alors même que les classes populaires en sont rejetées par le coût du logement et une fiscalité dissuasive. Effondrement du modèle intégrateur, ascenseur social en berne… Cette France à qui on demande de traverser la rue attend vainement, selon lui, que le feu repasse au vert pour elle. Guilluy la crédite cependant d’un « soft power », capacité, amplifiée par les réseaux sociaux, à remettre sur la table les sujets qui fâchent, ceux-là mêmes que les élites aimeraient conserver sous le tapis. Une donnée que les tribuns populistes, de droite comme de gauche, ont bien intégrée, s’en faisant complaisamment chambre d’écho. Sud Ouest

The slide in his popularity – Macron is now more unpopular than his predecessor, François Hollande, at the same stage – is a dire warning to “globalists”. It comes at a time when Trump’s popularity among his voters is relatively stable by comparison and the American economy is growing. Macron’s fate could have far-reaching consequences for Europe’s political future. What makes the contrast between Trump’s and Macron’s fortunes so striking is that the two presidents have so much in common. Both found electoral success by breaking free of their own side: Macron from the left and Trump from mainstream Republicanism; they both moved beyond the old left-right divide. Both realised that we were seeing the disappearance of the old western middle class. Both grasped that, for the first time in history, the working people who make up the solid base of the lower middle classes live, for the most part, in regions that now generate the fewest jobs. It is in the small or middling towns and vast stretches of farmland that skilled workers, the low-waged, small farmers and the self-employed are concentrated. These are the regions in which the future of western democracy will be decided. But the similarities end there. While Trump was elected by people in the heartlands of the American rustbelt states, Macron built his electoral momentum in the big globalised cities. While the French president is aware that social ties are weakening in the regions, he believes that the solution is to speed up reform to bring the country into line with the requirements of the global economy. Trump, by contrast, concluded that globalisation was the problem, and that the economic model it is based on would have to be reined in (through protectionism, limits on free trade agreements, controls on immigration, and spending on vast public infrastructure building) to create jobs in the deindustrialised parts of the US. It could be said that to some extent both presidents are implementing the policies they were elected to pursue. Yet, while Trump’s voters seem satisfied, Macron’s appear frustrated. Why is there such a difference? This has as much to do with the kind of voters involved as the way the two presidents operate politically. Trump speaks to voters who constitute a continuum, that of the old middle class. It is a body of voters with clearly expressed demands – most call for the creation of jobs, but they also want the preservation of their social and cultural model. Macron’s problem, on the other hand, is that his electorate consists of different elements that are hard to keep together. The idea that Macron was elected just by the big city “winners” isn’t accurate: he also attracted the support of many older voters who are not especially receptive to the economic and societal changes the president’s revolution demands.This holds true throughout Europe. Those who support globalisation often tend to forget a vital fact: the people who vote for them aren’t just the ones on the winning side in the globalisation stakes or part of the new, cool bourgeoisie in Paris, London or New York, but are a much more heterogeneous group, many of whom are sceptical about the effects of globalisation. In France, for example, most of Macron’s support came in the first instance from the ranks of pensioners and public sector workers who had been largely shielded from the effects of globalisation. (…) These developments are an illustration of the political difficulty that Europe’s globalising class now finds itself in. From Angela Merkel to Macron, the advocates of globalisation are now relying on voters who cling to a social model that held sway during the three decades of postwar economic growth. Thus their determination to accelerate the adaptation of western societies to globalisation automatically condemns them to political unpopularity. Locked away in their metropolitan citadels, they fail to see that their electoral programmes no longer meet the concerns of more than a tiny minority of the population – or worse, of their own voters. They are on the wrong track if they think that the “deplorables” in the deindustrialised states of the US or the struggling regions of France will soon die out. Throughout the west, people in “peripheral” regions still make up the bulk of the population. Like it or not, these areas continue to represent the electoral heartlands of western democracies. Christophe Guilluy

La focalisation sur le « problème des banlieues » fait oublier un fait majeur : 61 % de la population française vit aujourd’hui hors des grandes agglomérations. Les classes populaires se concentrent dorénavant dans les espaces périphériques : villes petites et moyennes, certains espaces périurbains et la France rurale. En outre, les banlieues sensibles ne sont nullement « abandonnées » par l’État. Comme l’a établi le sociologue Dominique Lorrain, les investissements publics dans le quartier des Hautes Noues à Villiers-sur-Marne (Val-de-Marne) sont mille fois supérieurs à ceux consentis en faveur d’un quartier modeste de la périphérie de Verdun (Meuse), qui n’a jamais attiré l’attention des médias. Pourtant, le revenu moyen par habitant de ce quartier de Villiers-sur-Marne est de 20 % supérieur à celui de Verdun. Bien sûr, c’est un exemple extrême. Il reste que, à l’échelle de la France, 85 % des ménages pauvres (qui gagnent moins de 993 € par mois, soit moins de 60 % du salaire médian, NDLR) ne vivent pas dans les quartiers « sensibles ». Si l’on retient le critère du PIB, la Seine-Saint-Denis est plus aisée que la Meuse ou l’Ariège. Le 93 n’est pas un espace de relégation, mais le cœur de l’aire parisienne. (…) En se désindustrialisant, les grandes villes ont besoin de beaucoup moins d’employés et d’ouvriers mais de davantage de cadres. C’est ce qu’on appelle la gentrification des grandes villes, symbolisée par la figure du fameux « bobo », partisan de l’ouverture dans tous les domaines. Confrontées à la flambée des prix dans le parc privé, les catégories populaires, pour leur part, cherchent des logements en dehors des grandes agglomérations. En outre, l’immobilier social, dernier parc accessible aux catégories populaires de ces métropoles, s’est spécialisé dans l’accueil des populations immigrées. Les catégories populaires d’origine européenne et qui sont éligibles au parc social s’efforcent d’éviter les quartiers où les HLM sont nombreux. Elles préfèrent déménager en grande banlieue, dans les petites villes ou les zones rurales pour accéder à la propriété et acquérir un pavillon. On assiste ainsi à l’émergence de « villes monde » très inégalitaires où se concentrent à la fois cadres et catégories populaires issues de l’immigration récente. Ce phénomène n’est pas limité à Paris. Il se constate dans toutes les agglomérations de France (Lyon, Bordeaux, Nantes, Lille, Grenoble), hormis Marseille. (…) On a du mal à formuler certains faits en France. Dans le vocabulaire de la politique de la ville, « classes moyennes » signifie en réalité « population d’origine européenne ». Or les HLM ne font plus coexister ces deux populations. L’immigration récente, pour l’essentiel familiale, s’est concentrée dans les quartiers de logements sociaux des grandes agglomérations, notamment les moins valorisés. Les derniers rapports de l’observatoire national des zones urbaines sensibles (ZUS) montrent qu’aujourd’hui 52 % des habitants des ZUS sont immigrés, chiffre qui atteint 64 % en Île-de-France. Cette spécialisation tend à se renforcer. La fin de la mixité dans les HLM n’est pas imputable aux bailleurs sociaux, qui font souvent beaucoup d’efforts. Mais on ne peut pas forcer des personnes qui ne le souhaitent pas à vivre ensemble. L’étalement urbain se poursuit parce que les habitants veulent se séparer, même si ça les fragilise économiquement. Par ailleurs, dans les territoires où se côtoient populations d’origine européenne et populations d’immigration extra-européenne, la fin du modèle assimilationniste suscite beaucoup d’inquiétudes. L’autre ne devient plus soi. Une société multiculturelle émerge. Minorités et majorités sont désormais relatives. (…) ces personnes habitent là où on produit les deux tiers du PIB du pays et où se crée l’essentiel des emplois, c’est-à-dire dans les métropoles. Une petite bourgeoisie issue de l’immigration maghrébine et africaine est ainsi apparue. Dans les ZUS, il existe une vraie mobilité géographique et sociale : les gens arrivent et partent. Ces quartiers servent de sas entre le Nord et le Sud. Ce constat ruine l’image misérabiliste d’une banlieue ghetto où seraient parqués des habitants condamnés à la pauvreté. À bien des égards, la politique de la ville est donc un grand succès. Les seuls phénomènes actuels d’ascension sociale dans les milieux populaires se constatent dans les catégories immigrées des métropoles. Cadres ou immigrés, tous les habitants des grandes agglomérations tirent bénéfice d’y vivre – chacun à leur échelle. En Grande-Bretagne, en 2013, le secrétaire d’État chargé des Universités et de la Science de l’époque, David Willetts, s’est même déclaré favorable à une politique de discrimination positive en faveur des jeunes hommes blancs de la « working class » car leur taux d’accès à l’université s’est effondré et est inférieur à celui des enfants d’immigrés. (…) Le problème social et politique majeur de la France, c’est que, pour la première fois depuis la révolution industrielle, la majeure partie des catégories populaires ne vit plus là où se crée la richesse. Au XIXe siècle, lors de la révolution industrielle, on a fait venir les paysans dans les grandes villes pour travailler en usine. Aujourd’hui, on les fait repartir à la « campagne ». C’est un retour en arrière de deux siècles. Le projet économique du pays, tourné vers la mondialisation, n’a plus besoin des catégories populaires, en quelque sorte. (…) L’absence d’intégration économique des catégories modestes explique le paradoxe français : un pays qui redistribue beaucoup de ses richesses mais dont une majorité d’habitants considèrent à juste titre qu’ils sont de plus en plus fragiles et déclassés. (…) Les catégories populaires qui vivent dans ces territoires sont d’autant plus attachées à leur environnement local qu’elles sont, en quelque sorte, assignées à résidence. Elles réagissent en portant une grande attention à ce que j’appelle le «village» : sa maison, son quartier, son territoire, son identité culturelle, qui représentent un capital social. La contre-société s’affirme aussi dans le domaine des valeurs. La France périphérique est attachée à l’ordre républicain, réservée envers les réformes de société et critique sur l’assistanat. L’accusation de «populisme» ne l’émeut guère. Elle ne supporte plus aucune forme de tutorat – ni politique, ni intellectuel – de la part de ceux qui se croient «éclairés». (…) Il devient très difficile de fédérer et de satisfaire tous les électorats à la fois. Dans un monde parfait, il faudrait pouvoir combiner le libéralisme économique et culturel dans les agglomérations et le protectionnisme, le refus du multiculturalisme et l’attachement aux valeurs traditionnelles dans la France périphérique. Mais c’est utopique. C’est pourquoi ces deux France décrivent les nouvelles fractures politiques, présentes et à venir. Christophe Guilluy