Malheur à vous, scribes et pharisiens hypocrites! parce que vous bâtissez les tombeaux des prophètes et ornez les sépulcres des justes, et que vous dites: Si nous avions vécu du temps de nos pères, nous ne nous serions pas joints à eux pour répandre le sang des prophètes. Vous témoignez ainsi contre vous-mêmes que vous êtes les fils de ceux qui ont tué les prophètes. Jésus (Matthieu 23: 29-31)

Ne croyez pas que je sois venu apporter la paix sur la terre; je ne suis pas venu apporter la paix, mais l’épée. Car je suis venu mettre la division entre l’homme et son père, entre la fille et sa mère, entre la belle-fille et sa belle-mère; et l’homme aura pour ennemis les gens de sa maison. Jésus (Matthieu 10 : 34-36)

Il n’y a plus ni Juif ni Grec, il n’y a plus ni esclave ni libre, il n’y a plus ni homme ni femme; car tous vous êtes un en Jésus Christ. Paul (Galates 3: 28)

Je pense qu’il y a plus de barbarie à manger un homme vivant qu’à le manger mort, à déchirer par tourments et par géhennes un corps encore plein de sentiment, le faire rôtir par le menu, le faire mordre et meurtrir aux chiens et aux pourceaux (comme nous l’avons non seulement lu, mais vu de fraîche mémoire, non entre des ennemis anciens, mais entre des voisins et concitoyens, et, qui pis est, sous prétexte de piété et de religion), que de le rôtir et manger après qu’il est trépassé. Il ne faut pas juger à l’aune de nos critères. (…) Je trouve… qu’il n’y a rien de barbare et de sauvage en cette nation, à ce qu’on m’en a rapporté, sinon que chacun appelle barbarie ce qui n’est pas de son usage. (…) Leur guerre est toute noble et généreuse, et a autant d’excuse et de beauté que cette maladie humaine en peut recevoir ; elle n’a d’autre fondement parmi eux que la seule jalousie de la vertu… Ils ne demandent à leurs prisonniers autre rançon que la confession et reconnaissance d’être vaincus ; mais il ne s’en trouve pas un, en tout un siècle, qui n’aime mieux la mort que de relâcher, ni par contenance, ni de parole, un seul point d’une grandeur de courage invincible ; il ne s’en voit aucun qui n’aime mieux être tué et mangé, que de requérir seulement de ne l’être pas. Ils les traitent en toute liberté, afin que la vie leur soit d’autant plus chère ; et les entretiennent communément des menaces de leur mort future, des tourments qu’ils y auront à souffrir, des apprêts qu’on dresse pour cet effet, du détranchement de leurs membres et du festin qui se fera à leurs dépens. Tout cela se fait pour cette seule fin d’arracher de leur bouche parole molle ou rabaissée, ou de leur donner envie de s’enfuir, pour gagner cet avantage de les avoir épouvantés, et d’avoir fait force à leur constance. Car aussi, à le bien prendre, c’est en ce seul point que consiste la vraie victoire. Montaigne

Etrange destinée, étrange préférence que celle de l’ethnographe, sinon de l’anthropologue, qui s’intéresse aux hommes des antipodes plutôt qu’à ses compatriotes, aux superstitions et aux mœurs les plus déconcertantes plutôt qu’aux siennes, comme si je ne sais quelle pudeur ou prudence l’en dissuadait au départ. Si je n’étais pas convaincu que les lumières de la psychanalyse sont fort douteuses, je me demanderais quel ressentiment se trouve sublimé dans cette fascination du lointain, étant bien entendu que refoulement et sublimation, loin d’entraîner de ma part quelque condamnation ou condescendance, me paraissent dans la plupart des cas authentiquement créateurs. (…) Peut-être cette sympathie fondamentale, indispensable pour le sérieux même du travail de l’ethnographe, celui-ci n’a-t-il aucun mal à l’acquérir. Il souffre plutôt d’un défaut symétrique de l’hostilité vulgaire que je relevais il y a un instant. Dès le début, Hérodote n’est pas avare d’éloges pour les Scythes, ni Tacite pour les Germains, dont il oppose complaisamment les vertus à la corruption impériale. Quoique évoque du Chiapas, Las Casas me semble plus occupé à défendre les Indiens qu’à les convertir. Il compare leur civilisation avec celle de l’antiquité gréco-latine et lui donne l’avantage. Les idoles, selon lui, résultent de l’obligation de recourir à des symboles communs à tous les fidèles. Quant aux sacrifices humains, explique-t-il, il ne convient pas de s’y opposer par la force, car ils témoignent de la grande et sincère piété des Mexicains qui, dans l’ignorance où ils se trouvent de la crucifixion du Sauveur, sont bien obligés de lui inventer un équivalent qui n’en soit pas indigne. Je ne pense pas que l’esprit missionnaire explique entièrement un parti-pris de compréhension, que rien ne rebute. La croyance au bon sauvage est peut-être congénitale de l’ethnologie. (…) Nous avons eu les oreilles rebattues de la sagesse des Chinois, inventant la poudre sans s’en servir que pour les feux d’artifice. Certes. Mais, d’une part l’Occident a connu lui aussi la poudre sans longtemps l’employer pour la guerre. Au IXe siècle, le Livre des Feux, de Marcus Graecus en contient déjà la formule ; il faudra attendre plusieurs centaines d’années pour son utilisation militaire, très exactement jusqu’à l’invention de la bombarde, qui permet d’en exploiter la puissance de déflagration. Quant aux Chinois, dès qu’ils ont connu les canons, ils en ont été acheteurs très empressés, avant qu’ils n’en fabriquent eux-mêmes, d’abord avec l’aide d’ingénieurs européens. Dans l’Afrique contemporaine, seule la pauvreté ralentit le remplacement du pilon par les appareils ménagers fabriqués à Saint-Étienne ou à Milan. Mais la misère n’interdit pas l’invasion des récipients en plastique au détriment des poteries et des vanneries traditionnelles. Les plus élégantes des coquettes Foulbé se vêtent de cotonnades imprimées venues des Pays-Bas ou du Japon. Le même phénomène se produit d’ailleurs de façon encore plus accélérée dans la civilisation scientifique et industrielle, béate d’admiration devant toute mécanique nouvelle et ordinateur à clignotants. (…) Je déplore autant qu’un autre la disparition progressive d’un tel capital d’art, de finesse, d’harmonie. Mais je suis tout aussi impuissant contre les avantages du béton et de l’électricité. Je ne me sens d’ailleurs pas le courage d’expliquer leur privilège à ceux qui en manquent. (…) Les indigènes ne se résignent pas à demeurer objets d’études et de musées, parfois habitants de réserves où l’on s’ingénie à les protéger du progrès. Étudiants, boursiers, ouvriers transplantés, ils n’ajoutent guère foi à l’éloquence des tentateurs, car ils en savent peu qui abandonnent leur civilisation pour cet état sauvage qu’ils louent avec effusion. Ils n’ignorent pas que ces savants sont venus les étudier avec sympathie, compréhension, admiration, qu’ils ont partagé leur vie. Mais la rancune leur suggère que leurs hôtes passagers étaient là d’abord pour écrire une thèse, pour conquérir un diplôme, puisqu’ils sont retournés enseigner à leurs élèves les coutumes étranges, « primitives », qu’ils avaient observées, et qu’ils ont retrouvé là-bas du même coup auto, téléphone, chauffage central, réfrigérateur, les mille commodités que la technique traîne après soi. Dès lors, comment ne pas être exaspéré d’entendre ces bons apôtres vanter les conditions de félicité rustique, d’équilibre et de sagesse simple que garantit l’analphabétisme ? Éveillées à des ambitions neuves, les générations qui étudient et qui naguère étaient étudiées, n’écoutent pas sans sarcasme ces discours flatteurs où ils croient reconnaître l’accent attendri des riches, quand ils expliquent aux pauvres que l’argent ne fait pas le bonheur, – encore moins, sans doute, ne le font les ressources de la civilisation industrielle. À d’autres. Roger Caillois (1974)

Le monde moderne n’est pas mauvais : à certains égards, il est bien trop bon. Il est rempli de vertus féroces et gâchées. Lorsqu’un dispositif religieux est brisé (comme le fut le christianisme pendant la Réforme), ce ne sont pas seulement les vices qui sont libérés. Les vices sont en effet libérés, et ils errent de par le monde en faisant des ravages ; mais les vertus le sont aussi, et elles errent plus férocement encore en faisant des ravages plus terribles. Le monde moderne est saturé des vieilles vertus chrétiennes virant à la folie. G.K. Chesterton

L’inauguration majestueuse de l’ère « post-chrétienne » est une plaisanterie. Nous sommes dans un ultra-christianisme caricatural qui essaie d’échapper à l’orbite judéo-chrétienne en « radicalisant » le souci des victimes dans un sens antichrétien. René Girard

Nous sommes encore proches de cette période des grandes expositions internationales qui regardait de façon utopique la mondialisation comme l’Exposition de Londres – la « Fameuse » dont parle Dostoievski, les expositions de Paris… Plus on s’approche de la vraie mondialisation plus on s’aperçoit que la non-différence ce n’est pas du tout la paix parmi les hommes mais ce peut être la rivalité mimétique la plus extravagante. On était encore dans cette idée selon laquelle on vivait dans le même monde: on n’est plus séparé par rien de ce qui séparait les hommes auparavant donc c’est forcément le paradis. Ce que voulait la Révolution française. Après la nuit du 4 août, plus de problème ! René Girard

Nous sommes entrés dans un mouvement qui est de l’ordre du religieux. Entrés dans la mécanique du sacrilège : la victime, dans nos sociétés, est entourée de l’aura du sacré. Du coup, l’écriture de l’histoire, la recherche universitaire, se retrouvent soumises à l’appréciation du législateur et du juge comme, autrefois, à celle de la Sorbonne ecclésiastique. Françoise Chandernagor

Malgré le titre général, en effet, dès l’article 1, seules la traite transatlantique et la traite qui, dans l’océan Indien, amena des Africains à l’île Maurice et à la Réunion sont considérées comme « crime contre l’humanité ». Ni la traite et l’esclavage arabes, ni la traite interafricaine, pourtant très importants et plus étalés dans le temps puisque certains ont duré jusque dans les années 1980 (au Mali et en Mauritanie par exemple), ne sont concernés. Le crime contre l’humanité qu’est l’esclavage est réduit, par la loi Taubira, à l’esclavage imposé par les Européens et à la traite transatlantique. (…) Faute d’avoir le droit de voter, comme les Parlements étrangers, des « résolutions », des voeux, bref des bonnes paroles, le Parlement français, lorsqu’il veut consoler ou faire plaisir, ne peut le faire que par la loi. (…) On a l’impression que la France se pose en gardienne de la mémoire universelle et qu’elle se repent, même à la place d’autrui, de tous les péchés du passé. Je ne sais si c’est la marque d’un orgueil excessif ou d’une excessive humilité mais, en tout cas, c’est excessif ! […] Ces lois, déjà votées ou proposées au Parlement, sont dangereuses parce qu’elles violent le droit et, parfois, l’histoire. La plupart d’entre elles, déjà, violent délibérément la Constitution, en particulier ses articles 34 et 37. (…) les parlementaires savent qu’ils violent la Constitution mais ils n’en ont cure. Pourquoi ? Parce que l’organe chargé de veiller au respect de la Constitution par le Parlement, c’est le Conseil constitutionnel. Or, qui peut le saisir ? Ni vous, ni moi : aucun citoyen, ni groupe de citoyens, aucun juge même, ne peut saisir le Conseil constitutionnel, et lui-même ne peut pas s’autosaisir. Il ne peut être saisi que par le président de la République, le Premier ministre, les présidents des Assemblées ou 60 députés. (…) La liberté d’expression, c’est fragile, récent, et ce n’est pas total : il est nécessaire de pouvoir punir, le cas échéant, la diffamation et les injures raciales, les incitations à la haine, l’atteinte à la mémoire des morts, etc. Tout cela, dans la loi sur la presse de 1881 modifiée, était poursuivi et puni bien avant les lois mémorielles. Françoise Chandernagor

La tendance à légiférer sur le passé (…) est née des procédures lancées, dans les années 1970, contre d’anciens nazis et collaborateurs ayant participé à l’extermination des juifs. Celles-ci utilisaient pour la première fois l’imprescriptibilité des crimes contre l’humanité, votée en 1964. Elles devaient aboutir aux procès Barbie, Touvier et Papon. (…) L’innovation juridique des « procès pour la mémoire » se justifiait, certes, par l’importance et la singularité du génocide des juifs, dont la signification n’est apparue que deux générations plus tard. Elle exprimait cependant un changement radical dans la place que nos sociétés assignent à l’histoire, dont on n’a pas fini de prendre la mesure. Ces procès ont soulevé la question de savoir si, un demi-siècle après, les juges étaient toujours « contemporains » des faits incriminés. Ils ont montré à quel point la culture de la mémoire avait pris le pas, non seulement sur les politiques de l’oubli qui émergent après une guerre ou une guerre civile, afin de permettre une reconstruction, mais aussi sur la connaissance historique elle-même. L’illusion est ici de croire que la « mémoire » fabrique de l’identité sociale, qu’elle donne accès à la connaissance. Comment peut-on se souvenir de ce que l’on ignore, les historiens ayant précisément pour fonction, non de « remémorer » des faits, des acteurs, des processus du passé, mais bien de les établir ? Dans le cas du génocide des juifs, dans celui des Arméniens ou dans le cas de la guerre d’Algérie, encore pouvons-nous avoir le sentiment que ces faits appartiennent toujours au temps présent — que l’on soit ou non favorable aux « repentances ». L’identification reste possible de victimes précises, directes ou indirectes, et de bourreaux singuliers, individus ou Etats, à qui l’on peut demander réparation. Mais comment peut-on prétendre agir de la même manière sur des faits vieux de plusieurs siècles ? Comment penser sérieusement que l’on peut « réparer » les dommages causés par la traite négrière « à partir du XVe siècle » de la même manière que les crimes nazis, dont certains bourreaux habitent encore au coin de la rue ? (…) Pourquoi (…) promulguer une loi à seule fin rétroactive s’il n’y a aucune possibilité d’identifier des bourreaux, encore moins de les traîner devant un tribunal ? Pourquoi devons-nous être à ce point tributaires d’un passé qui nous est aussi étranger ? Pourquoi cette volonté d’abolir la distance temporelle et de proclamer que les crimes d’il y a quatre siècles ont des effets encore opérants ? Pourquoi cette réduction de l’histoire à la seule dimension criminelle et mortifère ? Et comment croire que les valeurs de notre temps sont à ce point estimables qu’elles puissent ainsi s’appliquer à tout ce qui nous a précédés ? En réalité, la plupart de ces initiatives relèvent de la surenchère politique. Elles sont la conséquence de la place que la plupart des pays démocratiques ont accordée au souvenir de la Shoah, érigé en symbole universel de la lutte contre toutes les formes de racisme. A l’évidence, le caractère universel de la démarche échappe à beaucoup. La mémoire de la Shoah est ainsi devenue un modèle jalousé, donc, à la fois, récusé et imitable : d’où l’urgence de recourir à la notion anachronique de crime contre l’humanité pour des faits vieux de trois ou quatre cents ans. Le passé n’est ici qu’un substitut, une construction artificielle — et dangereuse —, puisque le groupe n’est plus défini par une filiation passée ou une condition sociale présente, mais par un lien « historique » élaboré après coup, pour isoler une nouvelle catégorie à offrir à la compassion publique. Enfin, cette faiblesse s’exprime, une fois de plus, par un recours paradoxal à l’Etat, voie habituelle, en France, pour donner consistance à une « communauté » au sein de la nation. Sommé d’assumer tous les méfaits du passé, l’Etat se retrouve en même temps source du crime et source de rédemption. Outre la contradiction, cette « continuité » semble dire que l’histoire ne serait qu’un bloc, la diversité et l’évolution des hommes et des idées, une simple vue de l’esprit, et l’Etat, le seul garant d’une nouvelle histoire officielle « vertueuse ». C’est là une conception pour le moins réactionnaire de la liberté et du progrès. Henry Rousso

La loi (…) portant reconnaissance de la nation et contribution nationale en faveur des Français rapatriés » risque, surtout en ses articles 1 et 4, de relancer une polémique dans laquelle les historiens ne se reconnaîtront guère. En officialisant le point de vue de groupes de mémoire liés à la colonisation, elle risque de générer en retour des simplismes symétriques, émanant de groupes de mémoire antagonistes, dont l' »histoire officielle » , telle que l’envisage cette loi, fait des exclus de l’histoire. Car, si les injonctions « colonialophiles » de la loi ne sont pas recevables, le discours victimisant ordinaire ne l’est pas davantage, ne serait-ce que parce qu’il permet commodément de mettre le mouchoir sur tant d’autres ignominies, actuelles ou anciennes, et qui ne sont pas forcément du ressort originel de l’impérialisme ou de ses formes historiques passées comme le(s) colonialisme(s). L’étude scientifique du passé ne peut se faire sous la coupe d’une victimisation et d’un culpabilisme corollaire. De ce point de vue, les débordements émotionnels portés par les »indigènes de la République » ne sont pas de mise. Des êtres humains ne sont pas responsables des ignominies commises par leurs ancêtres – ou alors il faudrait que les Allemands continuent éternellement à payer leur épisode nazi. C’est une chose d’analyser, par exemple, les « zoos humains » de la colonisation. C’en est une autre que de confondre dans la commisération culpabilisante le « divers historique », lequel ne se réduit pas à des clichés médiatiquement martelés. Si la colonisation fut ressentie par les colonisés dans le rejet et la douleur, elle fut aussi vécue par certains dans l’ouverture, pour le modèle de société qu’elle offrait pour sortir de l’étouffoir communautaire. (…)Les historiens doivent travailler à reconstruire les faits et à les porter à la connaissance du public. Or ces faits établissent que la traite des esclaves, dans laquelle des Européens ont été impliqués (et encore, pas eux seuls), a porté sur environ 11 millions de personnes (27,5 % des 40 millions d’esclaves déportés), et que les trafiquants arabes s’y sont taillé la part du lion : la »traite orientale » fut responsable de la déportation de 17 millions de personnes (42,5 % d’entre eux) et la traite « interne » effectuée à l’intérieur de l’Afrique, porta, elle, sur 12 millions (30 %). Cela, ni Dieudonné ni les « Indigènes » , dans leur texte victimisant à sens unique, ne le disent – même si, à l’évidence, la traite européenne fut plus concentrée dans le temps et plus rentable en termes de nombre de déportés par an. (…) L’historien ne se reconnaît pas dans l’affrontement des mémoires. Pour lui, elles ne sont que des documents historiques, à traiter comme tels. Il ne se reconnaît pas dans l’anachronisme, qui veut tout arrimer au passé ; il ne se reconnaît pas dans le manichéisme, qu’il provienne de la »nostalgérie » électoraliste vulgaire qui a présidé à la loi du 23 février 2005, ou qu’il provienne des simplismes symétriques qui surfent sur les duretés du présent pour emboucher les trompettes agressives d’un ressentiment déconnecté de son objet réel. Gilbert Meynier

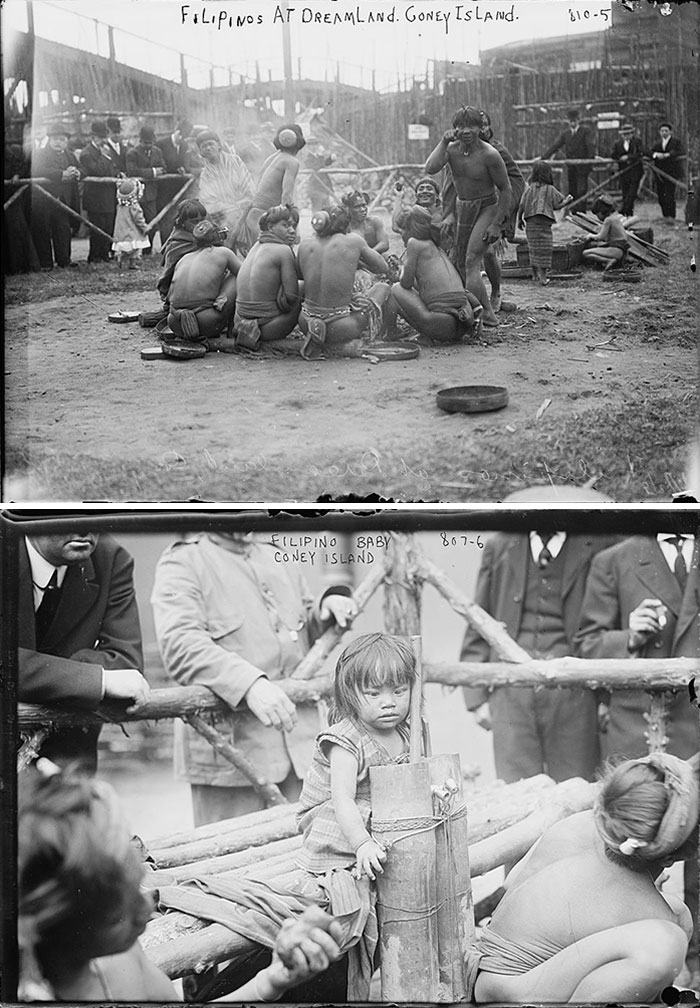

The enigmatic showman Martin Couney showcased premature babies in incubators to early 20th century crowds on the Coney Island and Atlantic City boardwalks, and at expositions across the United States. A Prussian-born immigrant based on the East coast, Couney had no medical degree but called himself a physician, and his self-promoting carnival-barking incubator display exhibits actually ended up saving the lives of about 7,000 premature babies. These tiny infants would have died without Couney’s theatrics, but instead they grew into adulthood, had children, grandchildren, great grandchildren and lived into their 70s, 80s, and 90s. This extraordinary story reveals a great deal about neonatology, and about life. (…) Drawing on extraordinary archival research as well as interviews, [Raffel’s] narrative is enhanced by her own reflections as she balanced her shock over how Couney saved these premature infants and also managed to make a living by displaying them like little freaks to the vast crowds who came to see them. Couney’s work with premature infants began in Europe as a carnival barker at an incubator exposition. It was there he fell in love with preemies and met his head nurse Louise Recht. Still, even allowing for his evident affection, making the preemies incubation a public show seems exploitative. But was it? In the 21st century, hospital incubators and NICUs are taken for granted, but over a hundred years ago, incubators were rarely used in hospitals, and sometimes they did far more harm than good. Premature infants often went blind because of too much oxygen pumped into the incubators (Raffel notes that Stevie Wonder, himself a preemie, lost his sight this way). Yet the preemies Couney and his nurses — his wife Maye, his daughter Hildegard, and lead nurse Louise, known in the show as “Madame Recht” — cared for retained their vision. The reason? Couney was worried enough about this problem to use incubators developed by M. Alexandre Lion in France, which regulated oxygen flow. Today it is widely accept that every baby – premature or ones born to term – should be saved. Not so in Couney’s time. Preemies were referred to as “weaklings,” and even some doctors believed their lives were not worth saving. While Raffel’s tale is inspiring, it is also horrific. She does not shy away from people like Dr. Harry Haiselden who, unlike Couney, was an actual M.D., but “denied lifesaving treatment to infants he deemed ‘defective,’ deliberately watching them die even when they could have lived.” (…) True, he was a showman, and during most of his career, he earned a good living from his incubator babies show, but Couney, an elegant man who fluently spoke German, French and English, didn’t exploit his preemies (Hildegard was a preemie too). He gave them a chance at the lives they might not have been allowed to live. Couney used his showmanship to support all of this life-saving. He put on shows for boardwalk crowds, but he also, despite not having a medical degree, maintained his incubators according to high medical standards. In many ways, Couney’s practices were incredibly advanced. Babies were fed with breast milk exclusively, nurses provided loving touches frequently, and the babies were held, changed and bathed. (…) Yet the efforts of Dr. Couney’s his nurses went largely ignored by the medical profession and were only mentioned once in a medical journal. As Raffel writes in her book’s final page, “There is nothing at his grave to indicate that [Martin Couney] did anything of note.” The same goes for Maye, Louise and Hildegard. Louise’s name was misspelled on her shared tombstone (Louise’s remains are interred in another family’s crypt), and Hildegard, whose remains are interred with Louise’s, did not even have her own name engraved on the shared tombstone. With the exception of Chicago’s Dr. Julius Hess, who is considered the father of neonatology, the majority of the medical establishment patronized and excluded Couney. Hess, though, respected Couney’s work and built on it with his own scientific approach and research; in the preface to his book Premature and Congenitally Diseased Infants, Hess acknowledges Couney “‘for his many helpful suggestions in the preparation of the material for this book.’” But Couney cared more about the babies than professional respect. His was a single-minded focus: even when it financially devastated him to do so, he persisted, so his preemies could live. National Book Review

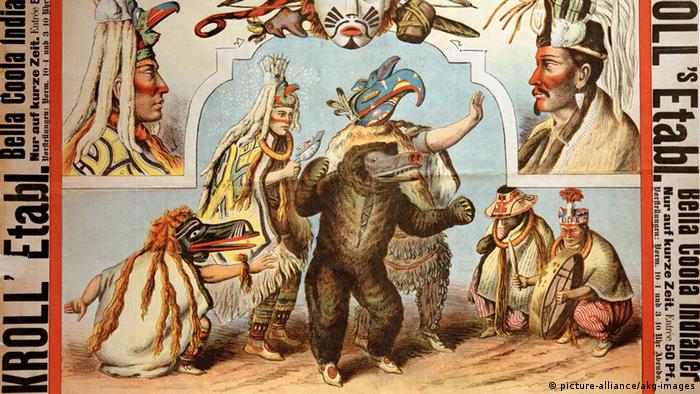

Carl Hagenbeck had the idea to open zoos that weren’t only filled with animals, but also people. People were excited to discover humans from abroad: Before television and color photography were available, it was their only way to see them. Anne Dreesbach

The main feature of these multiform varieties of public show, which became widespread in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Europe and the United States, was the live presence of individuals who were considered “primitive”. Whilst these native peoples sometimes gave demonstrations of their skills or produced manufactures for the audience, more often their role was simply as exhibits, to display their bodies and gestures, their different and singular condition. In this article, the three main forms of modern ethnic show (commercial, colonial and missionary) will be presented, together with a warning about the inadequacy of categorising all such spectacles under the label of “human zoos”, a term which has become common in both academic and media circles in recent years. Luis A. Sánchez-Gómez

Between the 29th of November 2011 and the 3rd of June 2012, the Quai de Branly Museum in Paris displayed an extraordinary exhibition, with the eye-catching title Exhibitions. L’invention du sauvage, which had a considerable social and media impact. Its “scientific curators” were the historian Pascal Blanchard and the museum’s curator Nanette Jacomijn Snoep, with Guadalupe-born former footballer Lilian Thuram acting as “commissioner general”. A popular sportsman, Thuram is also known in France for his staunch social and political commitment. The exhibition was the culmination (although probably not the end point) of a successful project which had started in Marseille in 2001 with the conference entitled Mémoire colonial: zoos humains? Corps Exotiques, corps enfermés, corps mesurés. Over time, successive publications of the papers presented at that first meeting have given rise to a genuine publishing saga, thus far including three French editions, one in Italian, one in English and another in German. This remarkable repertoire is completed by the impressive catalogue of the exhibition. All of the book titles (with the exception of the catalogue) make reference to “human zoos” as their object of study, although in none of them are the words followed by a question mark, as was the case at the Marseille conference. This would seem to define “human zoos” as a well-documented phenomenon, the essence of which has been well-established. Most significantly, despite reiterating the concept, neither the catalogue of the exhibition, nor the texts drawn up by the exhibit’s editorial authorities, provide a precise definition of what a human zoo is understood to be. Nevertheless, the editors seem to accept the concept as being applicable to all of the various forms of public show featured in the exhibition, all of which seem to have been designed with a shared contempt for and exclusion of the “other”. Therefore, the label “human zoo” implicitly applies to a variety of shows whose common aim was the public display of human beings, with the sole purpose of showing their peculiar morphological or ethnic condition. Both the typology of the events and the condition of the individuals shown vary widely: ranging from the (generally individual) presentation of persons with crippling pathologies (exotic or more often domestic freaks or “human monsters”) to singular physical conditions (giants, dwarves or extremely obese individuals) or the display of individuals, families or groups of exotic peoples or savages, arrived or more usually brought, from distant colonies. The purpose of the 2001 conference had been to present the available information about such shows, to encourage their study from an academic perspective and, most importantly, to publicly denounce these material and symbolic contexts of domination and stigmatisation, which would have had a prominent role in the complex and dense animalisation mechanisms of the colonised peoples by the “civilized West”. A scientific and editorial project guided by such intentions could not fail to draw widespread support from academic, social and journalistic quarters. Reviews of the original 2002 text and successive editions have, for the most part, been very positive, and praise for what was certainly an extraordinary exhibition (the one of 2012) has been even more unanimous. However, most commentators have limited their remarks to praising the important anti-racist content and criticisms of the colonial legacy, which are common to both undertakings. Only a few authors have drawn attention to certain conceptual and interpretative problems with the presumed object of study, the “human zoos”, problems which would undermine the project’s solidity. (…) Although the public display of human beings can be traced far back in history in many different contexts (war, funerals and sacred contexts, prisons, fairs, etc…) the configuration and expansion of different varieties of ethnic shows are closely and directly linked to two historical phenomena which lie at the very basis of modernity: exhibitions and colonialism. The former began to appear at national contests and competitions (both industrial and agricultural). These were organised in some European countries in the second half of the eighteenth century, but it was only in the century that followed that they acquired new and shocking material and symbolic dimensions, in the shape of the international or universal exhibition.The key date was 1851, when the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was held in London. The triumph of the London event, its rapid and continuing success in France and the increasing participation (which will be outlined) of indigenous peoples from the colonies, paved the way from the 1880s for a new exhibition model: the colonial exhibition (whether official or private, national or international) which almost always featured the presence of indigenous human beings. However, less spectacular exhibitions had already been organised on a smaller scale for many years, since about the mid-nineteenth century. Some of these were truly impressive events, which in some cases also featured native peoples. These were the early missionary (or ethnological-missionary) exhibitions, which initially were mainly British and Protestant, but later also Catholic. Finally, the unsophisticated ethnological exhibitions which had been typical in England (particularly in London) in the early-nineteenth century, underwent a gradual transformation from the middle of the century, which saw them develop into the most popular form of commercial ethnological exhibition. These changes were initially influenced by the famous US circus impresario P.T. Barnum’s human exhibitions. Later on, from 1874, Barnum’s displays were successfully reinterpreted (through the incorporation of wild animals and groups of exotic individuals) by Carl Hagenbeck.The second factor which was decisive in shaping the modern ethnic show was imperial colonialism, which gathered in momentum from the 1870s. The propagandising effect of imperialism was facilitated by two emerging scientific disciplines, physical anthropology and ethnology, which propagated colonial images and mystifications amid the metropolitan population. This, coupled with robust new levels of consumerism amongst the bourgeoisie and the upper strata of the working classes, had a greater impact upon our subject than the economic and geostrategic consequences of imperialism overseas. In fact, the new context of geopolitical, scientific and economic expansion turned the formerly “mysterious savages” into a relatively accessible object of study for certain sections of society. Regardless of how much was written about their exotic ways of life, or strange religious beliefs, the public always wanted more: seeking participation in more “intense” and “true” encounters and to feel part of that network of forces (political, economic, military, academic and religious) that ruled even the farthest corners of the world and its most primitive inhabitants.It was precisely the convergence of this web of interests and opportunities within the new exhibition universe that had already consolidated by the end of the 1870s, and which was to become the defining factor in the transition. From the older, popular model of human exhibitions which had dominated so far, we see a reduction in the numbers of exhibitions of isolated individuals classified as strange, monstrous or simply exotic, in favour of adequately-staged displays of families and groups of peoples considered savage or primitive, authentic living examples of humanity from a bygone age. Of course, this new interest, this new desire to see and feel the “other” was fostered not only by exhibition impresarios, but by industrialists and merchants who traded in the colonies, by colonial administrators and missionary societies. In turn, the process was driven forward by the strongly positive reaction of the public, who asked for more: more exoticism, more colonial products, more civilising missions, more conversions, more native populations submitted to the white man’s power; ultimately, more spectacle. Despite the differences that can be observed within the catalogue of exhibitions, their success hinged to a great extent upon a single factor: the representation or display of human beings labelled as exotic or savage, which today strikes us as unsettling and distasteful. It can therefore be of little surprise that most, if not all, of the visitors to the Quai de Branly Museum exhibiton of 2012 reacted to the ethnic shows with a fundamental question: how was it possible that such repulsive shows had been organised? Although many would simply respond with two words, domination and racism, the question is certainly more complex. In order to provide an answer, the content and meanings of the three main models or varieties of the modern ethnic show –commercial ethnological exhibitions, colonial exhibitions and missionary exhibitions– will be studied. (…) The opposition that missionary societies encountered at nineteenth-century international exhibitions encouraged them to organise events of their own. The first autonomous missionary events were Protestant and possibly took place prior to 1851. In any case, this has been confirmed as the year that the Methodist Wesleyan Missionary Society organised a missionary exhibition (which took place at the same time as the International Exhibition). Small in size and very simple in structure, it was held for only two days during the month of June, although it provided the extraordinary opportunity to see and acquire shells, corals and varied ethnographic materials (including idols) from Tonga and Fiji. The exhibition’s aim was very specific: to make a profit from ticket sales and the materials exhibited and to seek general support for the missionary enterprise.Whether or not they were directly influenced by the international event of 1851, the modest British missionary exhibitions of the mid-nineteenth century began to evolve rapidly from the 1870s, reaching truly spectacular proportions in the first third of the twentieth century. This enormous success was due to a particular set of circumstances which were not true for the Catholic sphere. Firstly, the exhibits were a fantastic source of propaganda, and furthermore, they generated a direct and immediate cash income. This is significant considering that Protestant church societies and committees neither depended upon, nor were linked to (at least not directly or officially) civil administration and almost all revenue came from the personal contributions of the faithful. Secondly, because Protestants organised their own events, there was no reason for them to participate in the official colonial exhibitions, with which the Catholic missions became repeatedly involved once the old prejudices of government had fallen away by the later years of the nineteenth century. In this way, evangelical communities were able to maintain their independence from the imperial enterprise, yet in a manner that did not preclude them from collaborating with it whenever it was in their interests to do so.However, whether Catholic or Protestant, the main characteristic of the missionary exhibitions in the timeframe of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, was their ethnological intent. The ethnographic objects of converted peoples (and of those who had yet to be converted) were noteworthy for their exoticism and rarity, and became a true magnet for audiences. They were also supposedly irrefutable proof of the “backward” and even “depraved” nature of such peoples, who had to be liberated by the redemptive missions which all Christians were expected to support spiritually and financially. But as tastes changed and the public began to lose interest, the exhibitions started to grow in size and complexity, and increasingly began to feature new attractions, such as dioramas and sculptures of native groups. Finally, the most sophisticated of them began to include the natives themselves as part of the show. It must be said that, but for rare exceptions, these were not exhibitions in the style of the famous German Völkerschauen or British ethnological exhibitions, but mere performances; in fact, the “guests” had already been baptized, were Christians, and allegedly willing to collaborate with their benefactors.Whilst the Protestant churches (British and North American alike) produced representations of indigenous peoples with the greatest frequency and intensity, it was (as far as we know) the (Italian) Catholic Church that had the dubious honour of being the first to display natives at a missionary exhibition, and did so in a clearly savagist and rudimentary fashion, which could even be described as brutal. This occurred in the religious section of the Italian-American Exhibition of Genoa in 1892. As a shocking addition to the usual ethnographic and missionary collections, seven natives were exhibited in front of the audience: four Fuegians and three Mapuches of both sexes (children, young and fully-grown adults) brought from America by missionaries. The Fuegians, who were dressed only in skins and armed with bows and arrows, spent their time inside a hut made from branches which had been built in the garden of the pavilion housing the missionary exhibition. The Mapuches were two young girls and a man; the three of them lived inside another hut, where they made handicrafts under the watchful eye of their keepers.The exhibition appears to have been a great success, but it must have been evident that the model was too simple in concept, and inhumanitarian in its approach to the indigenous people present. In fact, whilst subsequent exhibitions also featured a native presence (always Christianised) at the invitation of the clergy, the Catholic Church never again fell into such a rough presentation and representation of the obsolete and savage way of life of its converted. To provide an illustration of those times, now happily overcome by the missionary enterprise, Catholic congregations resorted to dioramas and sculptures, some of which were of superb technical and artistic quality.Although the Catholic Church may have organised the first live missionary exhibition, it should not be forgotten that they joined the exhibitional sphere much later than the evangelical churches. Also, a considerable number of their displays were associated with colonial events, something that the Protestant churches avoided. (…) Whilst it was the reformed churches that most readily incorporated native participation, they seemed to do so in a more sensitive and less brutalised manner than the Genoese Catholic Exhibition of 1892. (…) The exhibition model at these early-twentieth century Protestant events was very similar to the colonial model. Native villages were reconstructed and ethnographic collections were presented, alongside examples of local flora and fauna, and of course, an abundance of information about missionary work, in which its evangelising, educational, medical and welfare aspects were presented. Some of these were equally as attractive to the audience (irrespective of their religious beliefs) as contemporary colonial or commercial exhibitions. However, it may be noted that the participation of Christianised natives took a radically different form from those of the colonial and commercial world. Those who were most capable and had a good command of English served as guides in the sections corresponding to their places of origin, a task that they tended to carry out in traditional clothing. More frequently these new Christians assumed roles with less responsibility, such as the manufacture of handicrafts, the sale of exotic objects or the recreation of certain aspects of their previous way of life. The organisers justified their presence by claiming that they were merely actors, representing their now-forgotten savage way of life. This may very well have been the case. At the Protestant exhibitions of the 1920s and 1930s, the presence of indigens became progressively less common until it eventually disappeared. This notwithstanding, the organisers came to benefit from a living resource which complemented displays of ethnographic materials whilst being more attractive to the audience than the usual dioramas. This was a theatrical representation of the native way of life (combined with scenes of missionary interaction) by white volunteers (both men and women) who were duly made up and in some cases appeared alongside real natives. Some of these performances were short, but others consisted of several acts and featured dozens of characters on stage. Regardless of their form, these spectacles were inherent to almost any British and North American exhibition, although much less frequent in continental Europe.Since the 1960s, the Christian missionary exhibition (both Protestant and Catholic) has been conducted along very different lines from those which have been discussed here. All direct or indirect associations with colonialism have been definitively given up; it has broken with racial or ethnological interpretations of converted peoples, and strongly defends its reputed autonomy from any political groups or interests, without forgetting that the essence of evangelisation is to maximize the visibility of its educational and charitable work among the most disadvantaged. (…)The three most important categories of modern ethnic show –commercial ethnological exhibitions, colonial exhibitions and missionary exhibitions– have been examined. All three resorted, to varying degrees, to the exhibition of exotic human beings in order to capture the attention of their audience, and, ultimately, to achieve certain goals: be they success in business and personal enrichment, social, political or financial backing for the colonial enterprise, or support for missionary work. Whilst on occasion they coincided at the same point in time and within the same context of representation, the uniqueness of each form of exhibition has been emphasised. However, this does not mean that they are completely separate phenomena, or that their representation of exotic “otherness” is homogeneous.Missionary exhibitions displayed perhaps the most singular traits due to their spiritual vision. However, it is clear that many made a determined effort to produce direct, visual and emotional spectacles and some, in so doing, resorted to representations of natives which were very similar to those of colonial exhibitions. Can we speak then, of a convergence of designs and interests? I honestly do not think so. At many colonial exhibitions, organisers showed a clear intention to portray natives as fearsome, savage individuals (sometimes even describing them as cannibals) who somehow needed to be subjugated. Peoples who were considered, to a lesser or greater extent, to be civilised were also displayed (as at the interwar exhibitions). However, the purpose of this was often to publicise the success of the colonial enterprise in its campaign for “the domestication of the savage”, rather than to present a message of humanitarianism or universal fraternity. Missionary exhibitions provided information and material examples of the former way of life of the converted, in which natives demonstrated that they had abandoned their savage condition and participated in the exhibition for the greater glory of the evangelising mission. Moreover, they also became living evidence that something much more transcendent than any civilising process was taking place: that once they had been baptised, anyone, no matter how wild they had once been, could become part of the same universal Christian family.It is certainly true that the shows that the audiences enjoyed at all of these exhibitions (whether missionary, colonial or even commercial) were very similar. Yet in the case of the former, the act of exhibition took place in a significantly more humanitarian context than in the others. And while it is evident that indigenous cultures and peoples were clearly manipulated in their representation at missionary exhibitions, this did not mean that the exhibited native was merely a passive element in the game. And there is something more. The dominating and spectacular qualities present in almost all missionary exhibitions should not let us forget one last factor which was essential to their conception, their development and even their longevity: Christian faith. Without Christian faith there would have been no missionary exhibitions, and had anything similar been organised, it would not have had the same meaning. It was essential that authentic Christian faith existed within the ecclesiastical hierarchy and within those responsible for congregations, missionary societies and committees. But the faith that really made the exhibitions possible was the faith of the missionaries, of others who were involved in their implementation and, of course, of those who visited. Although it was never recognised as such, this was perhaps an uncritical faith, complacent in its acceptance of the ways in which human diversity was represented and with ethical values that occasionally came close to the limits of Christian morality. But it was a faith nonetheless, a faith which intensified and grew with each exhibition, which surely fuelled both Christian religiosity (Catholic and Protestant alike) and at least several years of missionary enterprise, years crucial for the imperialist expansionism of the West. It is an objective fact that the display of human beings at commercial and colonial shows was always much more explicit and degrading than at any missionary exhibition. To state what has just been proposed more bluntly: missionary exhibitions were not “human zoos”. However, it is less clear whether the remaining categories: are commercial and colonial exhibitions worthy of this assertion (human zoos), or were they polymorphic ethnic shows of a much greater complexity?The principal analytical obstacle to the use of the term “human zoo” is that it makes an immediate and direct association between all of these acts and contexts and the idea of a nineteenth-century zoo. The images of caged animals, growling and howling, may cause admiration, but also disgust; they may sometimes inspire tenderness, but are mainly something to be avoided and feared due to their savage and bestial condition. This was definitely the case for the organisers of the scientific and editorial project cited at the beginning of this article, so it can be no surprise that Carl Hagenbeck’s joint exhibitions of exotic animals and peoples were chosen as the frame of reference for human zoos. Although the authors state in the first edition that “the human zoo is not the exhibition of savagery but its construction” [“le zoo humain n’est pas l’exhibition de la sauvagerie, mais la construction de celle-ci”], the problem, as Blanckaert (2002) points out, is that this alleged construction or exhibitional structure was not present at most of the exhibitions under scrutiny, nor (and this is an added of mine) at those shown at the Exhibitions. Indeed, the expression “human zoo” establishes a model which does not fit with the meagre number of exhibitions of exotic individuals from the sixteenth, seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, nor with that of Saartjie Baartmann (the Hottentot Venus) of the early nineteenth century, much less with the freak shows of the twentieth century. Furthermore, this model can neither be compared to most of the nineteenth-century British human ethnological exhibitions, nor to most of the native villages of the colonial exhibitions, nor to the Wild West show of Buffalo Bill, let alone to the ruralist-traditionalist villages which were set up at many national and international exhibitions until the interwar period. Ultimately, their connection with many wandering “black villages” or “native villages” exhibited by impresarios at the end of the nineteenth century could also be disputed. Moreover, many of the shows organised by Hagenbeck number amongst the most professional in the exhibitional universe. The fact that they were held in zoos should not automatically imply that the circumstances in which they took place were more brutal or exploitative than those of any of the other ethnic shows.It is evident from all the shows which have been discussed, that the differential racial condition of the persons exhibited not only formed the basis of their exhibition, but may also have fostered and even founded racist reactions and attitudes held by the public. However, there are many other factors (political, economic and even aesthetic) which come into play and have barely been considered, which could be seen as encouraging admiration of the displays of bodies, gestures, skills, creations and knowledge which were seen as both exotic and seductive.In fact, the indiscriminate use of the very successful concept of “human zoo” generates two fundamental problems. Firstly it impedes our “true” knowledge of the object of study itself, that is, of the very varied ethnic shows which it intends to catalogue, given the great diversity of contexts, formats, persons in charge, objectives and materialisations that such enterprises have to offer. Secondly, the image of the zoo inevitably recreates the idea of an exhibition which is purely animalistic, where the only relationship is that which exists between exhibitor and exhibited: the complete domination of the latter (irrational beasts) by the former (rational beings). If we accept that the exhibited are treated merely as as more-or-less worthy animals, the consequences are twofold: a logical rejection of such shows past, present and future, and the visualization of the exhibited as passive victims of racism and capitalism in the West. It is therefore of no surprise that the research barely considers the role that these individuals may have played, the extent to which their participation in the show was voluntary and the interests which may have moved some of them to take part in these shows. Ultimately, no evaluation has been made of how these shows may have provided “opportunity contexts” for the exhibited, whether as commercial, colonial or missionary exhibitis. Whilst it is true that the exhibited peoples’ own voice is the hardest to record in any of these shows, greater effort could have been made in identifying and mapping them, as, when this happens, the results obtained are truly interesting. Before we conclude, it must be said that the proposed analysis does not intend to soften or justify the phenomenon of the ethnic show. Even in the least dramatic and exploitative cases it is evident that the essence of these shows was a marked inequality, in which every supposed “context of interaction” established a dichotomous relationship between black and white, North and South, colonisers and colonised, and ultimately, between dominators and dominated. My intention has been to propose a more-or-less classifying and clarifying approach to this varied world of human exhibitions, to make a basic inventory of their forms of representation and to determine which are the essential traits that define them, without losing sight of the contingent factors which they rely upon. Luis A. Sánchez-Gómez

Une théorie du complot (on parle aussi de conspirationnisme ou de complotisme) est un récit pseudo-scientifique, interprétant des faits réels comme étant le résultat de l’action d’un groupe caché, qui agirait secrètement et illégalement pour modifier le cours des événements en sa faveur, et au détriment de l’intérêt public. Incapable de faire la démonstration rigoureuse de ce qu’elle avance, la théorie du complot accuse ceux qui la remettent en cause d’être les complices de ce groupe caché. Elle contribue à semer la confusion, la désinformation, et la haine contre les individus ou groupes d’individus qu’elle stigmatise. (…) Derrière chaque actualité ayant des causes accidentelles ou naturelles (mort ou suicide d’une personnalité, crash d’avion, catastrophe naturelle, crise économique…), la théorie du complot cherche un ou des organisateurs secrets (gouvernement, communauté juive, francs-maçons…) qui auraient manipulé les événements dans l’ombre pour servir leurs intérêts : l’explication rationnelle ne suffit jamais. Et même si les événements ont une cause intentionnelle et des acteurs évidents (attentat, assassinat, révolution, guerre, coup d’État…), la théorie du complot va chercher à démontrer que cela a en réalité profité à un AUTRE groupe caché. C’est la méthode du bouc émissaire. (…) La théorie du complot voit les indices de celui-ci partout où vous ne les voyez pas, comme si les comploteurs laissaient volontairement des traces, visibles des seuls « initiés ». Messages cachés sur des paquets de cigarettes, visage du diable aperçu dans la fumée du World Trade Center, parcours de la manifestation Charlie Hebdo qui dessinerait la carte d’Israël… Tout devient prétexte à interprétation, sans preuve autre que l’imagination de celui qui croit découvrir ces symboles cachés. Comme le disait une série célèbre : « I want to believe ! » (…) La théorie du complot a le doute sélectif : elle critique systématiquement l’information émanant des autorités publiques ou scientifiques, tout en s’appuyant sur des certitudes ou des paroles « d’experts » qu’elle refuse de questionner. De même, pour expliquer un événement, elle monte en épingle des éléments secondaires en leur conférant une importance qu’ils n’ont pas, tout en écartant les éléments susceptibles de contrarier la thèse du complot. Son doute est à géométrie variable. (…) La théorie du complot tend à mélanger des faits et des spéculations sans distinguer entre les deux. Dans les « explications » qu’elle apporte aux événements, des éléments parfaitement avérés sont noués avec des éléments inexacts ou non vérifiés, invérifiables, voire carrément mensongers. Mais le fait qu’une argumentation ait des parties exactes n’a jamais suffi à la rendre dans son ensemble exacte ! (…) C’est une technique rhétorique qui vise à intimider celui qui y est confronté : il s’agit de le submerger par une série d’arguments empruntés à des champs très diversifiés de la connaissance, pour remplacer la qualité de l’argumentation par la quantité des (fausses) preuves. Histoire, géopolitique, physique, biologie… toutes les sciences sont convoquées – bien entendu, jamais de façon rigoureuse. Il s’agit de créer l’impression que, parmi tous les arguments avancés, « tout ne peut pas être faux », qu’ »il n’y a pas de fumée sans feu » (…) Incapables (et pour cause !) d’apporter la preuve définitive de ce qu’elle avance, la théorie du complot renverse la situation, en exigeant de ceux qui ne la partagent pas de prouver qu’ils ont raison. Mais comment démontrer que quelque chose qui n’existe pas… n’existe pas ? Un peu comme si on vous demandait de prouver que le Père Noël n’est pas réel. (…) A force de multiplier les procédés expliqués ci-dessus, les théories du complot peuvent être totalement incohérentes, recourant à des arguments qui ne peuvent tenir ensemble dans un même cadre logique, qui s’excluent mutuellement. Au fond, une seule chose importe : répéter, faute de pouvoir le démontrer, qu’on nous ment, qu’on nous cache quelque chose. #OnTeManipule !

Hoax[es], rumeurs, photos ou vidéos truquées… les fausses informations abondent sur internet. Parfois la désinformation va plus loin, et prend la forme de pseudo-théories à l’apparence scientifique qui vous mettent en garde : « On te manipule ! » A en croire ces « théoriciens » du complot, États, institutions et médias déploieraient des efforts systématiques pour tromper et manipuler les citoyens. Il faudrait ne croire personne… sauf ceux qui portent ces thèses complotistes ! Étrange, non ? Et si ceux qui dénoncent la manipulation étaient eux-mêmes en train de nous manipuler ? Oui, #OnTeManipule quand on invente des complots, quand on désigne des boucs émissaires, et quand on demande d’y croire, sans aucune preuve. Découvrez les bons réflexes à avoir pour garder son sens critique et prendre du recul par rapport aux informations qui circulent. On te manipule

Au jardin d’Acclimatation (…) le jour où nous étions allés voir les Cinghalais… Marcel Proust

As black South Africans, we’ve always been told our culture is uncivilised, our culture is backward. Because of social media platforms reinforcing these stereotypes it becomes harder. As a young person why would you want to celebrate something that is constantly being mocked on social media platforms? I, as a South African, want to celebrate my culture. Having my photos labelled as inappropriate or regarded as porn, I take that as a direct attack on my cultural heritage. I take it as a sign of ignorance. If I’m posing in a sexually suggestive manner that is one thing, but if I’m posting pictures of me standing there in my traditional attire, that is a completely different context. It gets so frustrating, so maddening to talk about it. You can shake your boobs in a music video and it’s fine, because its normalised. But you see a woman just standing there with their boobs out and then, oh, it’s offensive. Nobukhosi Mtshali

They started removing advertising from our videos, then the views started dropping, the revenues started dropping. We don’t care about the revenues, we care about the insult to our culture. You talk about community standards, but you’re only talking about western community, not African community. But they did not engage with that. They just said these are our standard terms, if you don’t like it then you don’t have to use the platform. (…) You are an organisation that perpetrates racism, and oppression of black people, beliefs, culture and values. Lazi Dlamini (TV Yabantu)

When the Mijikenda started wearing clothes, tourism slumped – besides the impact of insecurity. Senator Emma Mbura (Mombasa, Kenya, 2015)

Our culture and traditional dress are what attract tourists to our coast. There were times when you would enter a hotel and find our girls dance traditional Mijikenda dances. They would dance bare-chested, with their firm breasts for all to see. How will we attract back the tourists back if all our women are wearing modern clothes like jeans and miniskirts? When tourists come to Mombasa, they want to visit the Old Town and eat traditional Swahili and Arab food. And if they go to Mijikenda towns and villages, they want to see the traditional dress of the Mahando. I only want to see the tourism sector revamped. The coast depends on tourism. It has been a difficult ride for many locals since tourists stopped visiting. I once worked at a hotel and lost my job when tourists stopped coming, so I know what it feels like. Sen. Emma Mbura

I have not told anyone to go naked. But we must know where we came from. Senator Mbura

This is a culture of the past; the dignity of women must be maintained. Sheikh Abdullah al-Mandhry

Kenyans are funny. You shouted from rooftops, ‘my dress, my choice’ – now you condemn Emma Mbura. What changed? Sir Chege wa Kimani

Mijikenda women, like many other African tribes in Kenya, went topless before the arrival of the Arabs and British colonizers and the ensuing spread of Islam and Christianity. (…) Recent attacks – blamed on Somalia’s Al-Shabaab militant group and rising militancy among the youth – have led several western countries to issue travel advisories to their citizens against travelling to the area. After agriculture, tourism represents Kenya’s second biggest foreign currency earner. (…) Mbura’s suggestion has drawn the rebuke of many Kenyans… Primanews

Aujourd’hui, l’équation difficile est de trouver une jeune fille vierge. Et de trouver même des jeunes filles qui acceptent de se mettent à nu. Kaldaoussa

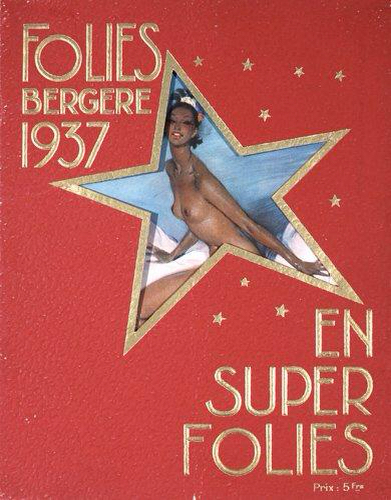

Dans le village traditionnel, il y aura des artisans et des danseurs. Non, la publicité n’était pas exagérée: dans la danse des jeunes filles, les seins sont nus. J’ai moi-même choisi tout le monde dans les villages de brousse. Ils sont tous volontaires et sont hébergés dans nos bâtiments. Ils vivent ici comme en Afrique: pour eux, il n’y a que le sol qui change… Dany Laurent

Le temps des expositions coloniales serait-il revenu? L’affaire que vient de révéler le Syndicat des musiciens CGT de Loire-Atlantique rappelle, en tout cas, beaucoup cette période peu glorieuse de la République. Elle fait grand bruit dans le département. Au ‘Safari Parc’ de Port-Saint-Père en Loire-Atlantique, vingt-cinq hommes, femmes et enfants venus tout droit de Côte-d’Ivoire, vont devoir, pendant sept mois, travailler, s’exposer et danser en tenue traditionnelle devant le public fréquentant le zoo. Il y a quelques jours, ‘Ouest France’ publiait en une une photo racoleuse ne correspondant guère à l’éthique déclarée de ce quotidien: une Africaine aux seins nus faisait de la publicité pour le ‘village africain’ de Port-Saint-Père. Ce beau parc animalier, créé il y a un an et qui bénéficie du soutien du conseil général, a déjà accueilli 450.000 visiteurs au milieu de ses 100 hectares, d’animaux et de constructions reconstituant l’univers africain. (…) Le directeur espère 600.000 visiteurs cette année et un grand succès touristique pour la Côte-d’Ivoire. Car, il le précise bien, « je ne suis pas l’employeur. J’ai signé une convention spéciale avec le ministère du Tourisme ivoirien, dont ces vingt-cinq personnes dépendent ». Résultat, les Africains n’ont pas de visa de travail, pas de salaire (une indemnité a été versée au village dont ils dépendent, et seul l’ancien de la troupe reçoit une somme d’argent, qu’il est chargé de distribuer à son gré. Pas de Sécurité sociale non plus. « En cas de maladie, ils seront rapatriés dans leur pays », annonce sans état d’âme le directeur. Interrogé sur la scolarisation des enfants, il explique qu’ils n’iront pas à l’école du village, mais seront pris en charge par l’ancien « comme dans une école de cirque », a-t-il déclaré à « Ouest France’. A l’aube de l’an 2000, on reste stupéfait devant une telle exhibition, digne des expositions coloniales d’antan. La vie des peuples africains aujourd’hui a-t-elle un quelconque rapport avec cette présentation en parallèle d’animaux vivant en semi-liberté et d’hommes et de femmes auquel on demande de mimer leur propre existence devant des touristes – sous un autre climat, dans une société qui leur est complètement étrangère et derrière les grilles d’un parc? Ce voyeurisme choque, alors même qu’à 30 kilomètres de là, à Nantes, ancien port négrier, une exposition sur la traite des Noirs, «Les anneaux de la mémoire» touche à sa fin… (…) « Ce sont les lois sociales françaises et le statut des artistes en représentation qui s’appliquent, cela d’autant plus que la troupe est là pour sept mois… » Une exception, dira-t-on? Tolérer ce genre d’accord, n’est-ce pas demain ouvrir la porte ici à une réserve d’Indiens, là un village d’Esquimaux, un bantoustan africain, tous sous-payés et échappant aux lois sociales. L’Humanité (13.04.1994)

Comment ne pas penser à ces enclos quand on voit les murs qui se construisent autour de l’Europe ou aux Etats-Unis ? Lilian Thuram

Peintures, sculptures, affiches, cartes postales, films, photographies, moulages, dioramas, maquettes et costumes donnent un aperçu de l’étendue de ce phénomène et du succès de cette industrie du spectacle exotique qui a fasciné plus d’un milliard de visiteurs de 1800 à 1958 et a concerné près de 35 000 figurants dans le monde. À travers un vaste panorama composé de près de 600 oeuvres et de nombreuses projections de films d’archives, l’exposition montre comment ces spectacles, à la fois outil de propagande, objet scientifique et source de divertissement, ont formé le regard de l’Occident et profondément influencé la manière dont est appréhendé l’Autre depuis près de cinq siècles. L’exposition explore les frontières parfois ténues entre exotiques et monstres, science et voyeurisme, exhibition et spectacle, et questionne le visiteur sur ses propres préjugés dans le monde d’aujourd’hui. Si ces exhibitions disparaissent progressivement dans les années 30, elles auront alors accompli leur oeuvre : créer une frontière entre les exhibés et les visiteurs. Une frontière dont on peut se demander si elle existe toujours ? Musée du quai Branly

Pendant plus d’un siècle, les grandes puissances colonisatrices ont exhibé comme des bêtes sauvages des êtres humains arrachés à leur terre natale. Retracée dans ce passionnant documentaire, cette « pratique » a servi bien des intérêts. Ils se nomment Petite Capeline, Tambo, Moliko, Ota Benga, Marius Kaloïe et Jean Thiam. Fuégienne de Patagonie, Aborigène d’Australie, Kali’na de Guyane, Pygmée du Congo, Kanak de Nouvelle-Calédonie, ces six-là, comme 35 000 autres entre 1810 et 1940, ont été arrachés à leur terre lointaine pour répondre à la curiosité d’un public en mal d’exotisme, dans les grandes métropoles occidentales. Présentés comme des monstres de foire, voire comme des cannibales, exhibés dans de véritables zoos humains, ils ont été source de distraction pour plus d’un milliard et demi d’Européens et d’Américains, venus les découvrir en famille au cirque ou dans des villages indigènes reconstitués, lors des grandes expositions universelles et coloniales. S’appuyant sur de riches archives (photos, films, journaux…) ainsi que sur le témoignage inédit des descendants de plusieurs de ces exhibés involontaires, Pascal Blanchard et Bruno Victor-Pujebet restituent le phénomène des exhibitions ethnographiques dans leur contexte historique, de l’émergence à l’essor des grands empires coloniaux. Ponctué d’éclairages de spécialistes et d’universitaires, parmi lesquels l’anthropologue Gilles Boëtsch (CNRS, Dakar) et les historiens Benjamin Stora, Sandrine Lemaire et Fanny Robles, leur passionnant récit permet d’appréhender la façon dont nos sociétés se sont construites en fabriquant, lors de grandes fêtes populaires, une représentation stéréotypée du « sauvage ». Et comment, succédant au racisme scientifique des débuts, a pu s’instituer un racisme populaire légitimant la domination des grandes puissances sur les autres peuples du monde. Arte

On assiste au passage progressif d’un racisme scientifique à un racisme populaire, un passage qui n’est ni lié à la littérature ni au cinéma, puisque celui-ci n’existe pas encore, mais à la culture populaire, avec des spectateurs qu vont au zoo pour se divertir, sans le sentiment d’être idéologisés, manipulés. Pascal Blanchard

On payait pour voir des êtres hors norme, le frisson de la dangerosité faisait partie du spectacle. (… ) Imaginez ici des pirogues, un décorum de village lacustre wolof. Tout était fait pour donner au public l’illusion de voir le sauvage dans son biotope. C’est d’ailleurs dans ce décor factice que les frères Lumière tourneront leur douzième film, Baignade de nègres, comme s’ils étaient en Afrique… Pour le visiteur, cette représentation caricaturale du monde et de l’autre était perçue comme la réalité. (…) Ces articles et ces photos contribuent alors à la propagation de clichés et d’idées reçues sur le “sauvage”. Autant de représentations qui légitiment l’ordre colonial, popularisent la théorie et la hiérarchie des races, le concept de peuples “inférieurs” qu’il convient de faire entrer dans la lumière de la civilisation. (…) Ici, vous aviez la grande esplanade des exhibitions humaines. Celle-là même où avaient été placés les Fuégiens de Patagonie en 1881. Sur les photos que nous avons pu retrouver, on voit qu’ils sont installés sur une planche, en hauteur, sans doute à cause du froid et de l’humidité. Ils étaient arrivés en plein mois d’octobre et n’étaient quasiment pas vêtus. Beaucoup avaient attrapé des maladies pulmonaires. (…) Ils étaient enterrés sur place, dans le cimetière du zoo, au même rang que les animaux. Dans certains cas, les corps étaient envoyés à l’Institut médico-légal ou à la Société d’anthropologie de Paris, où le public payait pour assister à leur dissection. (…) Même pour les spécialistes, ce pan de l’histoire coloniale était considéré comme un élément secondaire. (…) Il a fallu six mois pour obtenir l’autorisation de réaliser quelques séquences à l’intérieur du jardin, et nous ne l’avons eue que parce que nous avons menacé de filmer à travers les grilles… Pascal Blanchard

Grâce à l’historien Pascal Blanchard, que j’ai rencontré lors d’un colloque, à l’époque où je jouais à Barcelone. Après notre rencontre, il m’a envoyé un livre sur le sujet, et c’est comme ça que j’ai appris à connaître un peu mieux cette histoire des « zoos humains ». Une histoire extrêmement violente, dont les enjeux m’intéressent car elle permet de comprendre d’où vient le racisme, de saisir qu’il est lié à un conditionnement historique. (…) Les zoos humains sont le reflet d’un rapport de domination, celui de l’Occident sur le reste du monde. La domination de celui qui détient le pouvoir économique et militaire, et qui l’utilise pour que d’autres personnes, dominées, venues d’Asie, d’Océanie, d’Afrique, soient montrées comme des animaux dans des espaces clos, au nom notamment de la couleur de leur peau. (…) Ces exhibitions ont attiré des millions de spectateurs et ont ancré dans leur tête l’idée d’une hiérarchie entre les personnes, entre les prétendues « races » – la race blanche étant considérée comme supérieure. Les mécanismes de domination qui existent dans nos sociétés se sont construits petit à petit. La plupart des gens sont devenus racistes sans le savoir, ils ont été éduqués dans ce sens-là. Après avoir visité ces zoos humains, les populations occidentales étaient confortées dans l’idée qu’elles étaient supérieures, qu’elles incarnaient la « civilisation » face à des « sauvages ». Lorsque je préparais l’exposition au Quai Branly, en 2011, je me suis rendu à Hambourg. Là-bas, sur le portail d’entrée du zoo, une sculpture représente des animaux et des hommes, mis au même niveau. C’est d’une violence totale. Mais cela permet aussi de comprendre pourquoi certains sont aujourd’hui encore dans le rejet de l’autre. Il reste des séquelles de ce passé, les barrières existent toujours dans nos sociétés. Comment ne pas penser à ces enclos quand on voit les murs qui se construisent autour de l’Europe ou aux Etats-Unis ? Les zoos humains permettent de nous éclairer sur ce que nous vivons aujourd’hui. (…) Mais ce n’est pas seulement l’évocation des zoos humains qui pose problème, c’est le passé en général. Ce passé lié à de la violence, au fait de s’accaparer des biens d’autrui. Mais, ce passé-là, nous devons nous l’approprier car il raconte l’histoire du monde actuel. Le regarder en face doit nous permettre de nous éclairer sur ce que nous sommes en train de vivre, pour essayer de choisir un futur différent. Dans nos sociétés, la chose la plus importante est-elle le profit, le fait de s’octroyer le bien des autres pour s’enrichir ? C’est important de se poser ces questions-là aujourd’hui. (…) Ces manifestations racistes dont vous parlez viennent directement des zoos humains. De cette histoire. Les gens ont été éduqués ainsi. Les cultures dans lesquelles il y a eu des zoos humains gardent ce complexe de supériorité, conscient ou inconscient, sur les autres cultures. Pour progresser, il faut savoir faire preuve d’autocritique. Dans le sport de haut niveau, c’est essentiel. Cela vaut aussi pour la société. Mais nos sociétés, françaises, européennes, portent très peu de critiques sur elles-mêmes. Très souvent, les gens ne veulent pas critiquer leur propre culture. Il n’y a pas si longtemps encore, l’Europe était persuadée d’être le phare de l’univers. Les zoos humains sont liés à l’histoire coloniale. Les gens ont souvent tendance à croire qu’après la colonisation il y a eu l’égalité. Mais non, il y a une culture de la domination qui perdure. Notre système économique ne fait-il pas en sorte qu’une minorité, qui vit bien, exploite une majorité, qui vit mal ? (…) Avant toute chose, je pense qu’il faut connaître notre passé pour mieux comprendre ce que nous vivons aujourd’hui. Pourquoi certaines personnes ne veulent-elles pas connaître cette histoire, de quoi ont-elles peur ? Le plus beau cadeau que l’on puisse faire à une société, c’est de lui apprendre à connaître son histoire. Il n’y a que sur des bases solides que l’on peut construire un présent et un futur solides. Lilian Thuram

Entre 1877 et 1937, des millions de Parisiens se bousculèrent ici, à la lisière du bois de Boulogne, pour assister au spectacle exotique de Nubiens, Sénégalais, Kali’nas, Fuégiens, Lapons exposés devant le public parés de leurs attributs « authentiques » (lances, peaux de bêtes, pirogues, masques, bijoux…). On se pressait pour voir les « sauvages », des hommes, des femmes et des enfants souvent parqués derrière des grillages ou des barreaux, comme les animaux qui faisaient jusqu’alors la réputation du Jardin zoologique d’acclimatation. D’étranges étrangers, supposés non civilisés et potentiellement menaçants, à l’image de ces Kanaks présentés comme des cannibales et exhibés… dans la fosse aux ours. (…) Lorsque le directeur du Jardin d’acclimatation, le naturaliste Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, organise les tout premiers « spectacles ethnologiques » en 1877 avec des Nubiens et des Esquimaux, il est en quête de nouvelles attractions pour remettre à flot son établissement. Quelques mois plus tôt, à Hambourg, un certain Carl Hagenbeck, marchand d’animaux sauvages, a connu un succès phénoménal en présentant une troupe de Lapons. Au bois de Boulogne, le premier ethnic show fait courir les foules. La fréquentation du jardin double, pour atteindre un million de visiteurs en un an. Certains dimanches, plus de soixante-dix mille personnes se pressent dans les allées. C’est le début d’une mode qui va gagner le monde entier, d’expositions coloniales en expositions universelles. Trente-cinq mille individus seront ainsi exhibés, attirant près d’un milliard et demi de curieux de l’Allemagne aux Etats-Unis, de la Grande-Bretagne au Japon. Pour le promeneur de 2018, impossible de deviner ce passé sinistre derrière les contours ripolinés du parc d’attractions. Les bâtiments de l’époque ont été démolis. Quant aux villages exotiques qui servaient de cadre aux « indigènes », ils étaient éphémères, un ailleurs succédant à un autre. Mais Pascal Blanchard, qui a compulsé des kilos d’images d’archives, n’a aucun mal à en faire ressurgir le souvenir face à ce paisible plan d’eau où patientent des barques (…) Une réalité dont on pouvait conserver le souvenir en s’offrant, après le show, ses produits dérivés, cartes postales, gravures ou coquillages samoans signés de la main des indigènes. Les exhibitions coloniales font le bonheur des anthropologues, qui se bousculent chaque matin avant l’arrivée du public et payent pour pouvoir observer et examiner les « spécimens », publiant ensuite des articles dans les revues les plus sérieuses. S’inspirant des clichés anthropométriques de la police, le photographe Roland Bonaparte constitue, lui, un catalogue de plusieurs milliers d’images « ethnographiques », dans lequel puiseront des générations de scientifiques. (…) Nombre d’exhibés sont ainsi morts dans les zoos humains. On estime entre trente-deux et trente-quatre le nombre de ceux qui auraient péri au Jardin d’acclimatation. » L’acte de décès était déposé à la mairie de Neuilly, mais les morts n’avaient le plus souvent pas de nom. C’est à la lettre « F » comme Fuégienne que les chercheurs ont retrouvé, sur les registres, la trace d’une fillette de 2 ans morte peu après son arrivée à Paris. Une des pièces du puzzle qu’il a fallu patiemment assembler pour reconstituer la mémoire des zoos humains, longtemps ignorée de tous. (…) Aujourd’hui encore, le sujet reste sensible, y compris pour la direction du Jardin d’acclimatation (géré par le groupe LVMH), comme l’a constaté Pascal Blanchard lors du tournage de son documentaire (…) En 2013, au terme d’un combat de cinq ans, les historiens, soutenus par Didier Daeninckx, Lilian Thuram et des élus du Conseil de Paris, ont obtenu que soit posée au Jardin d’acclimatation une plaque commémorative faisant état de ce qu’avaient été les « zoos humains », « symboles d’une autre époque où l’autre avait été regardé comme un “animal” en Occident ». Mais le visiteur doit avoir l’œil bien ouvert pour remarquer la discrète inscription un peu cachée dans les herbes, à l’extérieur de l’enceinte du jardin… Comme le signe d’un passé refoulé qui peine encore à atteindre la lumière. Télérama

« Grandes puissances colonisatrices », « exhibés comme des bêtes sauvages », « êtres humains arrachés à leur terre natale », « servi bien des intérêts », « curiosité d’un public en mal d’exotisme », « présentés comme des monstres de foire, voire comme des cannibales, « véritables zoos humains », « théâtre de cruauté », « exhibés involontaires », « représentation stéréotypée du ‘sauvage' », « racisme scientifique », « racisme populaire légitimant la domination des grandes puissances sur les autres peuples du monde », « voyages dans wagons à bestiaux », « histoire inventée de toutes pièces » et « mise en scène pour promouvoir la hiérarchisation des races et justifier la colonisation du monde », « page sombre de notre histoire », « séquelles toujours vivaces » …

Au lendemain, après l’exposition du Quai Branly de 2011, de la diffusion d’un nouveau documentaire sur les « zoos humains » …

Où, à grands coups d’anachronismes et de raccourcis entre le narrateur de couleur de rigueur (le joueur de football guadeloupéen Lilian Thuram sautant allégrement des « zoos humains » aux cris de singe des hooligans des stades de football ou aux actuelles barrières de sécurité contre l’immigration llégale « Comment ne pas penser à ces enclos quand on voit les murs qui se construisent autour de l’Europe ou aux Etats-Unis ? »), la musique angoissante et les appels incessants à l’indignation, l’on nous déploie tout l’arsenal juridico-victimaire de l’histoire à la sauce tribunal de l’histoire …

Où faisant fi de toutes causes accidentelles ou naturelles (maladies, mort ou suicide), plus aucun fait ne peut être que le « résultat de l’action d’un groupe caché » au détriment de l’intérêt de populations qui ne peuvent autres que victimes …