Ne croyez pas que je sois venu apporter la paix sur la terre; je ne suis pas venu apporter la paix, mais l’épée. Car je suis venu mettre la division entre l’homme et son père, entre la fille et sa mère, entre la belle-fille et sa belle-mère; et l’homme aura pour ennemis les gens de sa maison. Jésus (Matthieu 10 : 34-36)

Il n’y a plus ni Juif ni Grec, il n’y a plus ni esclave ni libre, il n’y a plus ni homme ni femme; car tous vous êtes un en Jésus Christ. Paul (Galates 3: 28)

Depuis que l’ordre religieux est ébranlé – comme le christianisme le fut sous la Réforme – les vices ne sont pas seuls à se trouver libérés. Certes les vices sont libérés et ils errent à l’aventure et ils font des ravages. Mais les vertus aussi sont libérées et elles errent, plus farouches encore, et elles font des ravages plus terribles encore. Le monde moderne est envahi des veilles vertus chrétiennes devenues folles. Les vertus sont devenues folles pour avoir été isolées les unes des autres, contraintes à errer chacune en sa solitude. Chesterton

Il faut peut-être entendre par démocratie les vices de quelques-uns à la portée du plus grand nombre. Henry Becque

On a commencé avec la déconstruction du langage et on finit avec la déconstruction de l’être humain dans le laboratoire. (…) Elle est proposée par les mêmes qui d’un côté veulent prolonger la vie indéfiniment et nous disent de l’autre que le monde est surpeuplé. René Girard

Les images violentes accroissent (…) la vulnérabilité des enfants à la violence des groupes (…) rendent la violence ‘ordinaire’ en désensibilisant les spectateurs à ses effets, et elles augmentent la peur d’être soi-même victime de violences, même s’il n’y a pas de risque objectif à cela. Serge Tisseron

Si j’étais législateur, je proposerais tout simplement la disparition du mot et du concept de “mariage” dans un code civil et laïque. Le “mariage”, valeur religieuse, sacrale, hétérosexuelle – avec voeu de procréation, de fidélité éternelle, etc. -, c’est une concession de l’Etat laïque à l’Eglise chrétienne – en particulier dans son monogamisme qui n’est ni juif (il ne fut imposé aux juifs par les Européens qu’au siècle dernier et ne constituait pas une obligation il y a quelques générations au Maghreb juif) ni, cela on le sait bien, musulman. En supprimant le mot et le concept de “mariage”, cette équivoque ou cette hypocrisie religieuse et sacrale, qui n’a aucune place dans une constitution laïque, on les remplacerait par une “union civile” contractuelle, une sorte de pacs généralisé, amélioré, raffiné, souple et ajusté entre des partenaires de sexe ou de nombre non imposé.(…) C’est une utopie mais je prends date. Jacques Derrida

C’est le sens de l’histoire (…) Pour la première fois en Occident, des hommes et des femmes homosexuels prétendent se passer de l’acte sexuel pour fonder une famille. Ils transgressent un ordre procréatif qui a reposé, depuis 2000 ans, sur le principe de la différence sexuelle. Evelyne Roudinesco

Il m’était arrivé plusieurs fois que certains gosses ouvrent ma braguette et commencent à me chatouiller. Je réagissais de manière différente selon les circonstances, mais leur désir me posait un problème. Je leur demandais : « Pourquoi ne jouez-vous pas ensemble, pourquoi m’avez-vous choisi, moi, et pas d’autres gosses? » Mais s’ils insistaient, je les caressais quand même ». Daniel Cohn-Bendit (Grand Bazar, 1975)

La profusion de jeunes garçons très attrayants et immédiatement disponibles me met dans un état de désir que je n’ai plus besoin de réfréner ou d’occulter. (…) Je n’ai pas d’autre compte à régler que d’aligner mes bahts, et je suis libre, absolument libre de jouer avec mon désir et de choisir. La morale occidentale, la culpabilité de toujours, la honte que je traîne volent en éclats ; et que le monde aille à sa perte, comme dirait l’autre. Frédéric Mitterrand (”La mauvaise vie”, 2005)

Ce ne sont pas les différences qui provoquent les conflits mais leur effacement. René Girard

En présence de la diversité, nous nous replions sur nous-mêmes. Nous agissons comme des tortues. L’effet de la diversité est pire que ce qui avait été imaginé. Et ce n’est pas seulement que nous ne faisons plus confiance à ceux qui ne sont pas comme nous. Dans les communautés diverses, nous ne faisons plus confiance à ceux qui nous ressemblent. Robert Putnam

Illegal and illiberal immigration exists and will continue to expand because too many special interests are invested in it. It is one of those rare anomalies — the farm bill is another — that crosses political party lines and instead unites disparate elites through their diverse but shared self-interests: live-and-let-live profits for some and raw political power for others. For corporate employers, millions of poor foreign nationals ensure cheap labor, with the state picking up the eventual social costs. For Democratic politicos, illegal immigration translates into continued expansion of favorable political demography in the American Southwest. For ethnic activists, huge annual influxes of unassimilated minorities subvert the odious melting pot and mean continuance of their own self-appointed guardianship of salad-bowl multiculturalism. Meanwhile, the upper middle classes in coastal cocoons enjoy the aristocratic privileges of having plenty of cheap household help, while having enough wealth not to worry about the social costs of illegal immigration in terms of higher taxes or the problems in public education, law enforcement, and entitlements. No wonder our elites wink and nod at the supposed realities in the current immigration bill, while selling fantasies to the majority of skeptical Americans. Victor Davis Hanson

Who are the bigots — the rude and unruly protestors who scream and swarm drop-off points and angrily block immigration authority buses to prevent the release of children into their communities, or the shrill counter-protestors who chant back “Viva La Raza” (“Long Live the Race”)? For that matter, how does the racialist term “La Raza” survive as an acceptable title of a national lobby group in this politically correct age of anger at the Washington Redskins football brand? How can American immigration authorities simply send immigrant kids all over the United States and drop them into communities without firm guarantees of waiting sponsors or family? If private charities did that, would the operators be jailed? Would American parents be arrested for putting their unescorted kids on buses headed out of state? Liberal elites talk down to the cash-strapped middle class about their illiberal anger over the current immigration crisis. But most sermonizers are hypocritical. Take Nancy Pelosi, former speaker of the House. She lectures about the need for near-instant amnesty for thousands streaming across the border. But Pelosi is a multimillionaire, and thus rich enough not to worry about the increased costs and higher taxes needed to offer instant social services to the new arrivals. Progressives and ethnic activists see in open borders extralegal ways to gain future constituents dependent on an ever-growing government, with instilled grudges against any who might not welcome their flouting of U.S. laws. How moral is that? Likewise, the CEOs of Silicon Valley and Wall Street who want cheap labor from south of the border assume that their own offspring’s private academies will not be affected by thousands of undocumented immigrants, that their own neighborhoods will remain non-integrated, and that their own medical services and specialists’ waiting rooms will not be made available to the poor arrivals. … What a strange, selfish, and callous alliance of rich corporate grandees, cynical left-wing politicians, and ethnic chauvinists who have conspired to erode U.S. law for their own narrow interests, all the while smearing those who object as xenophobes, racists, and nativists. Victor Davis Hanson

Selon Stanley Cohen (1972), une « panique morale » surgit quand « une condition, un événement, une personne ou un groupe de personnes est désigné comme une menace pour les valeurs et les intérêts d’une société ». Le sociologue propose également qu’on reconnaisse dans toute « panique morale » deux acteurs majeurs : les « chefs moraux » (« moral entrepreneurs »), initiateurs de la dénonciation collective ; et les « boucs-émissaires » (« folk devils »), personnes ou groupes désignés à la vindicte. Des chercheurs spécialisés dans la culture numérique, tels Henry Jenkins aux Etats-Unis, ou Hervé Le Crosnier, maître de conférence à l’université de Caen, utilisent également le terme de panique morale pour désigner la peur disproportionnée des médias et d’une partie de la population face à la transformation induite par tout changement technologique, perçue comme un grand danger à la portée de chacun. Les « paniques morales » sont souvent liées à des controverses, et sont généralement nourries par une couverture médiatique intense (bien que des paniques semi-spontanées puissent exister. L’hystérie collective peut être une composante de ces mouvements, mais la panique morale s’en distingue parce que constitutivement interprétée en termes de moralité. Elle s’exprime habituellement davantage en termes d’offense ou d’outrage qu’en termes de peur. Les « paniques morales » (telles que définies par Stanley Cohen) s’articulent autour d’un élément perçu comme un danger pour une valeur ou une norme défendue par la société ou mise en avant par les médias ou institutions. L’un des aspects les plus marquants des paniques morales est leur capacité à s’auto-entretenir. La médiatisation d’une panique tendant à légitimer celle-ci et à faire apparaître le problème (parfois illusoire), comme bien réel et plus important qu’il n’est. La médiatisation de la panique engendrant alors un accroissement de la panique. Les effets de ce genre de réactions sont par ailleurs nombreux dans le domaine politique et juridique. (…) Le terme « panique morale » a été inventé par Stanley Cohen (en 1972 pour décrire la couverture médiatique des Mods et des Rockers au Royaume-Uni dans les années soixante. On fait remonter aux Middletown Studies, conduites en 1925 pour la première fois, la première analyse en profondeur de ce phénomène : les chercheurs découvrirent que les communautés religieuses américaines et leurs chefs locaux condamnaient alors les nouvelles technologies comme la radio ou l’automobile en arguant qu’elles faisait la promotion de conduites immorales. Un pasteur interrogé dans cette étude désignait ainsi l’automobile comme une « maison close sur roues » et condamnait cette invention au motif qu’elle donnait aux citoyens le moyen de quitter la ville alors qu’ils auraient dû être à l’église. Cependant, dès les années 30, Wilhem Reich avait développé le concept de peste émotionnelle qui, sous une forme plus radicale, est la base théorique de la panique morale. (…) Le risque lié aux paniques morales est multiple. Les plus importants sont de ne plus croire ce qui est rapporté par les médias ou même de ne plus croire les informations justes, constituant ainsi le terreau du complotisme qui se répand au XXIe siècle avec la prédominance des échanges sur internet. C’est aussi mettre sur un même plan d’importance des éléments pourtant très différents. Ainsi, certaines paniques dites “mineures” par Divan Frau-Meigs pourraient se retrouver à une même importance que des paniques morales majeures (le traitement de l’obésité au même niveau que la peur du terrorisme par exemple). Wikipedia

It has been Cohen’s longstanding contention that the term moral panic is, for its utility, problematic insofar as the term ‘panic’ implies an irrational reaction which a researcher is rejecting in the very act of labelling it such. That was the case when he was studying the media coverage of the Mods and Rockers and when Young was studying the reaction to drug taking in the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Currently , Cohen has started to feel uncomfortable with the blanket application the term ’panic’ in the study of any reactions to deviance, as he argues for its possible use in ‘good moral panics’. Cohen discusses the changes that have occurred in society and how this has had re-directed the ‘moral panic’ analysis and has contributed to the development of the concept. To begin with, the modern moral entrepreneurs have adopted a status similar to the social analyst (in terms of class, education and ideology) and the likelihood for the two of them to perceive the problem in the same way has increased substantially. Secondly, the alliances between the various political forces has become more flexible and as a result, panics about ‘genuine’ victims (of natural disasters or terrorist attacks) are more likely to generate consensus that the ‘unworthy’ victims (the homeless). Thirdly, whereas the traditional moral panics where in nature elite-engineered, the contemporary ones are much more likely to populist-based, giving more space for social movements’ and victims’ participation in the process. Fourthly, in contrast to the old moral panics, the new ones are interventionist-focused. The new criminalizers who address the moral panics are either post-liberals who share a common background with a decriminalized generation, or are from the new right who argue for increased focus on private morality (sexuality, abortion, lifestyle). In addition, Cohen considers the possibility of certain moral panics being understood as ‘anti-denial’ movements. In contemporary times the denial of certain events, their cover-up, evasion and tolerance is perceived as morally wrong, and such denied realities should be brought to the public attention, which would result in widespread moral condemnation and denunciation. In this sense, it could be argued that certain panics should also be considered as ‘acceptable’ and thus a binarity between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ moral panics can be developed. Such as heuristic between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ can be useful as such a distinction in effect widens the scope of moral panic studies beyond those examples that are regarded as ‘inappropriate’ and ‘irrational’. Potentially, this could also lead to the questioning of the notions of rationality, disproportionality and other normative judgements that have characterised the studies of moral panics. Such an approach of analysing ‘moral panics’ is in contrast with the work of Critcher, to whom the concept of can be best understood in the relations of power and regulation. Whereas both Critcher and Cohen agree that each moral panic should be seen in a wider conceptual framework, the latter does not adopt Critcher’s suggestion that the term ‘moral’ panic should not be applied in cases where dominant elites reinforce dominant practices by way of scapegoating outsiders. By contrast to Critcher, Cohen accepts the possibility of counter-hegemonic moral panics. In addition, Critcher stresses the need to focus not only on the politics of moral panics, but also consider the economic factors that might limit or promote their development. Moving beyond moral panics, Hunt has argued that a shift has taken place in the processes of moral regulation over the past century, whereby the boundaries that separate morality from immorality have been blurred. As a result, an increasing number of everyday activities have become moralized and the expression of such moralization can be found in hybrid configurations of risk and harm. The moralization of everyday life contains a dialectic that counterposes individualizing discourses against collectivizing discourses and moralization has become an increasingly common feature of contemporary political discourse. Moral panics can also be seen as volatile manifestations of an ongoing project of moral regulation, where the ‘moral’ is represented as practices that are specifically designed to promote the care of the self. With the shift towards neo-liberalism, such regulatory scripts have taken the form of discourses of risk, harm and personal responsibility. As Hier the implementation of such a ‘personalization’ discourse is not straightforward due to the fact that moral callings are not always accepted. The moral codes that are supposed to regulate behaviour, expression and self-presentation are themselves contestable and their operation is not bound in a time-space frame. Thus, ‘moralization’ is conceptualized as a recurrent sequence of attempts to negotiate social life; a temporary ‘crisis’ of the ‘code’ (moral panic) is therefore far more routine than extraordinary. The problems with such an argument for expanding the focus of moral panics to encompass forms of moral regulation is that it is too broad and a more specific scope of moral regulation should be defined in order to conduct such analysis. Dimitar Panchev (2013)

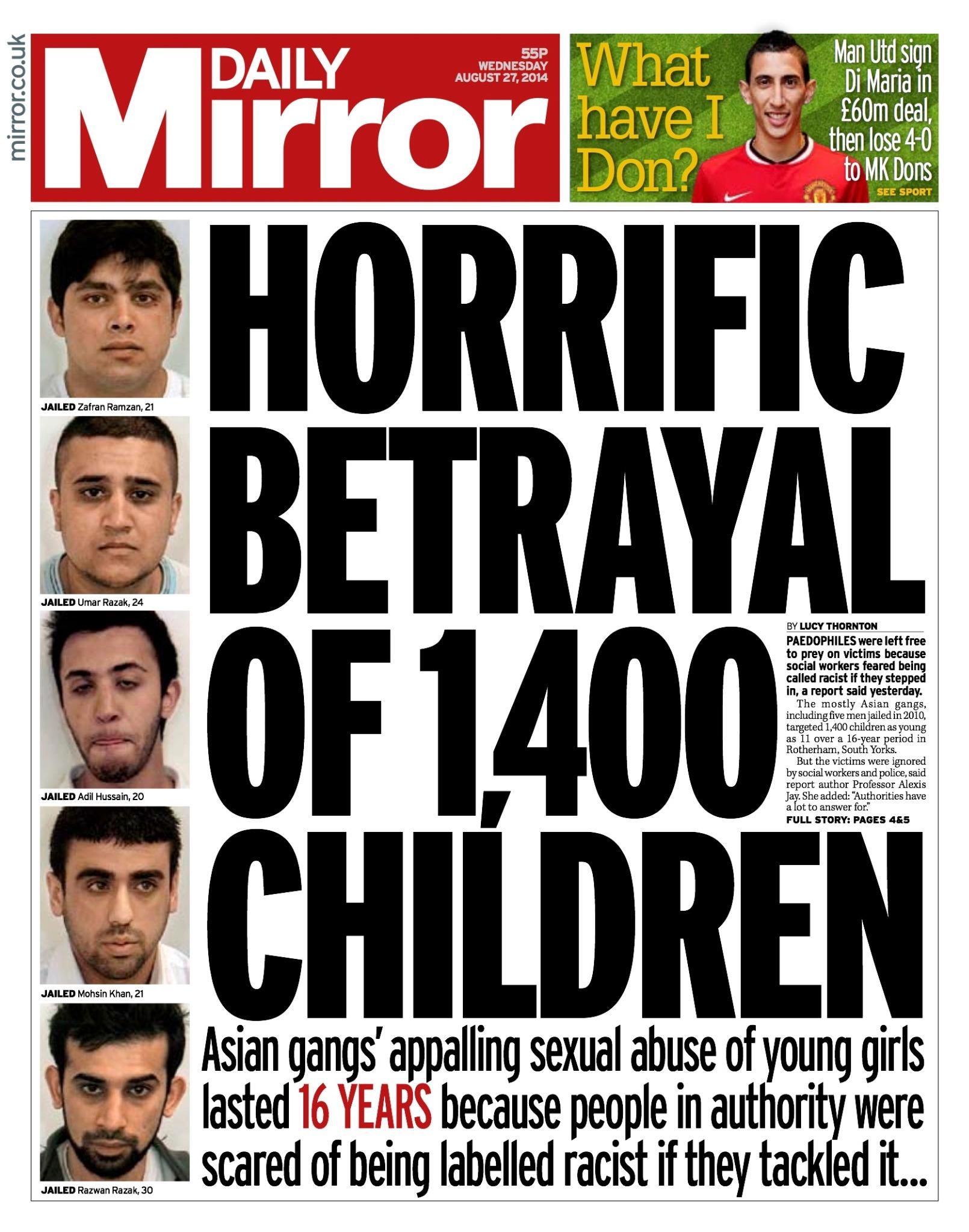

« Cela fait six mois que le mouvement #MeToo a pris son essor. Cela fait maintenant six mois que nous recevons régulièrement des articles attirant l’attention sur les souffrances apparentes des femmes aux mains des hommes. Ainsi, lorsque le Sunday Mirror de ce week-end a révélé les abus choquants subis par des centaines de femmes et de filles à Telford, nous aurions pu nous attendre à ce que l’indignation trouve un nouveau point de mire. La nouvelle selon laquelle des filles, dont certaines n’avaient que 11 ans, ont été droguées, battues et violées par des bandes d’hommes principalement musulmans et d’origine asiatique aurait pu alimenter davantage les campagnes. Nous aurions pu nous attendre à des manifestations de solidarité, à des rappels de l’importance de croire la victime et à des offres de soutien financier. Mais non. On estime que les abus commis à Telford ont concerné plus de 1 000 filles pendant 40 ans. Les jeunes filles de la ville ont été manipulées, droguées et violées. Elles passaient d’un abuseur à l’autre comme des marchandises. Certaines sont tombées enceintes, ont avorté et ont été violées à plusieurs reprises. Trois femmes ont été assassinées et deux autres sont mortes dans des tragédies liées à ces abus. Pourtant, ces événements choquants ont été relativement peu médiatisés. Les filles de Telford ne méritent pas, semble-t-il, de faire la une du Guardian ou du Times. Les mêmes journaux qui ont couvert, longuement et pendant de nombreux jours, l’information selon laquelle le genou de Kate Maltby avait ou non été touché par Damian Green ou que Michael Fallon avait tenté d’embrasser Jane Merrick, ont été incapables de rassembler le même niveau d’indignation pour les jeunes femmes de Telford. Johanna Williams

« We do more workshops in middle schools than in high schools, » says Bell, executive director of Bebashi-Transition to Hope, the local nonprofit that works on prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. « Teachers call us because their kids are acting out sexually. They’ll catch them in the bathroom or the stairwell. They hear that kids are cutting schools to have orgies. » (…) « We follow 200 teenagers with HIV, and the youngest is 12, » says Jill Foster, director of the Dorothy Mann Center for Pediatric and Adolescent HIV at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children. « When we started doing HIV treatment in 1998, the average age of patients was 16 or 17. The first time we got a 13-year-old was mind-blowing. » (…) Because a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified Philadelphia as having the earliest age of sexual initiation – 13 – among cities participating in the study, she says, it’s crucial to make condoms available to younger kids. People gasp at that, says Foster, who diagnoses new HIV cases at a rate of two to three teens a month, up from one every four months just a decade ago. « But people have no idea how tough it is to be a kid who’s exposed to sexual media images and peer pressure. It’s routine for 12- and 13-year-olds to talk about sex. Younger kids hear them and they want to be part of that ‘older’ world, » she says. « They don’t have maturity or impulse control, so if we can get them to have condoms with them when they start having sex, they are going to be safer. « I wish it weren’t necessary, » she says. « Unfortunately, it is. » It would be easy to play the « appalled citizen » card and decry the inclusion of kids as young as 11 in Philadelphia’s STD-prevention campaign. But I won’t. Because there are two groups of children in this city: Those lucky enough to have at least one caring, available adult to guide them through sex-charged adolescence. And those left on their own. Like the child being raised by a single mom whose two jobs keep her from supervising her child. Or the kids being raised by a tired grandmom who’s asleep by 9 and doesn’t know that the kids have snuck out of the house. Or the homeless teen who crashes on couches and must choose between saying no to a friend’s creepy uncle or wandering the streets at night. These kids deserve protection from the fallout of STDs and unplanned pregnancy as much as kids from « good » families do – kids who, by the way, get in trouble, too. They just have more support to get them through it. « We know that sexual activity in young adolescents doesn’t change overnight, » says Donald Schwarz, a physician who worked with adolescents for years at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia before being appointed city health commissioner in 2008. « But children need to be protected while we get our heads around whatever the long-term strategies should be here. » He mentions a recent, awful survey of sixth-graders in West Philly, which showed that 25 percent of the children, who were just 11 years old, had had sex. « Clearly, we don’t think it’s OK for 11-year-olds to be having sex, » says Schwarz. « But we don’t have the infrastructure in place to fix [that] problem fast. We can, however, make condoms available fairly quickly to whoever needs them. (…) There are no easy solutions. This is a complicated problem, exacerbated by generational poverty and family collapse that paralyzes our cities in ways too myriad to address in one column. Ronnie Polaneczky

Giving out free condoms at school is not a surefire way to avoid teenage pregnancy – or it might not be enough. Access to condoms in schools increases teen fertility rates by about 10 per cent, according to a new study by the University Of Notre Dame. However the increase happened in schools where no counseling was provided when condoms were given out – and giving out guidance as well as birth control could have the opposite effect, economists Kasey Buckles and Daniel Hungerman said in the study. Access to other kinds of birth control, such as the contraceptive pill, IUDs and implants, has been shown to lower teen fertility rates – but condoms might have opposite consequences due to their failure rate as well as the time and frequency at which they’re used. (…) Times have changed already and teenagers today are overall less likely to have sex and less likely to become pregnant, they wrote. Most of the free condoms programs in the study began in 1992 or 1993 and about two thirds involved mandatory counseling. The 10 per cent increased occurred as a result of schools that gave out condoms without counseling, Buckles and Hungerman said. ‘These fertility effects may have been attenuated, or perhaps even reversed, when counseling was mandated as part of condom provision,’ they wrote. Teenage girls were also more likely to develop gonorrhea when condoms were given for free – and again, the increase happened as a result of schools giving out condoms without counseling. Access to contraceptives in general has been shown to lower teen fertility, Buckles and Hungerman noted, or in some cases had no effect at all. But condoms might have a different impact because of several factors, such as the fact that their failure rate is more important than that of other contraceptives. Condoms also rely ‘more heavily on the male partner’, which is an important factor given that an unplanned pregnancy will have different consequences for each gender, Buckle and Hungerman wrote. The time at which condoms are used could also explain why they have a different impact than other types of birth control. Condoms have to be used at the time of intercourse, whereas the pill, IUDs and implants are all taken in advance. Using condoms also results from a short-term decision rather than long-term. Free condom programs in schools could have led to two additional births per 1,000 teenage women so far, Buckle and Hungerman found. This could increase to 5 extra births per 1,000 teenage girls if the country’s entire high-school-aged population had access to condoms. Condom distribution programs could promote the use of condoms over more efficient birth control methods, drive schools to use their resources for condom distribution rather than more effective programs, or might encourage ‘risky’ sexual behaviors, Buckle and Hungerman wrote. Daily Mail

L’upskirt (anglicisme argotique, littéralement « sous la jupe ») est une forme d’érotisme ou de pornographie particulièrement présente sur Internet, constituée de photographies ou de videos prises sous les jupes des femmes (le plus souvent en contre-plongée en position debout, ou de face en position assise), dans le but de montrer leurs sous-vêtements, voire leurs parties génitales et/ou leurs fesses. Bien que les prises de vues puissent être faites avec le consentement des sujets, les spectateurs de ce type de scènes recherchent le plus souvent des clichés pris furtivement, notamment dans des lieux publics, et donc, selon toute vraisemblance, à l’insu des personnes représentées, ce qui fait de l’upskirt une forme de voyeurisme. L’avènement des téléphones mobiles équipés d’appareils photo et de caméras est souvent présenté comme étant à l’origine du développement de cette pratique, mais en réalité, l’upskirt existe depuis que la mode a démocratisé la minijupe, c’est-à-dire vers le milieu des années 60. Une telle pratique sans le consentement de la personne photographiée peut être considérée comme illégale dans certaines juridictions. Wikipedia

Critiqué par ses fans pour avoir accepté de chanter lors de la cérémonie d’ouverture de la Coupe du monde, Robbie Williams a terminé sa prestation en faisant un doigt d’honneur. Un geste, réalisé juste après avoir rajouté un «I did it for free» dans les paroles de «Rock DJ», qui a immédiatement été très commenté sur les réseaux sociaux. L’Equipe

il s’agit de respecter une souffrance. Samia Maktouf (avocate de familles de victimes de l’attentat islamiste du Bataclan en réaction à la programmation dans la salle d’un certain Médine ayant intitulé l’un de ses disques « Jihad »)

Finalement, Viktor Orban pourrait avoir gagné. Le maître de Budapest fut le premier à dresser des barbelés contre l’exode, celui des Syriens en août 2015. Sa prophétie n’est pas loin de se réaliser quand l’Italie, jusqu’ici ouverte à la misère du monde, renvoie en pleine mer un bâtiment chargé de 629 migrants africains. Basculement. Électrochoc. Malgré le trouble d’Angela Merkel et les blâmes d’Emmanuel Macron, la question pour l’Europe n’est plus de savoir si elle doit renforcer sa frontière commune. Mais si elle peut encore éviter le retour aux barrières nationales. En trois ans, l’exception hongroise s’est propagée à toute l’Europe centrale. Varsovie, Prague et Bratislava jurent avec Budapest que la religion musulmane n’est pas soluble dans l’UE. Tous applaudissent le coup de force italien. À ce quatuor de Visegrad, il faudrait désormais ajouter un trio d’acteurs qui va de l’extrême droite à la droite dure: l’Italien Matteo Salvini, l’Autriche de Sebastian Kurz et Horst Seehofer, monument bavarois et ministre allemand de l’Intérieur. Ces trois-là forment le nouvel «axe» anti-immigration que décrit le jeune chancelier autrichien, avant de prendre la présidence tournante de l’UE le 1er juillet. La fronde dessine un périmètre curieusement semblable à celui de l’empire des Habsbourg. Elle est aussi pétrie de contradictions. Même s’ils partagent la hantise de l’islam, Viktor Orban et ses amis d’Europe centrale se garderont bien de rejoindre l’axe autrichien. Et inversement. À l’intérieur de l’axe alpin, la pire chose qui puisse arriver au chancelier Kurz serait que Matteo Salvini, nouvel homme fort du pouvoir romain, obtienne ce qu’il demande: le partage avec le reste de l’Europe – Autriche comprise – de tout ou partie des quelque 500.000 «irréguliers» qui croupissent en Italie. Quant au projet prêté à Horst Seehofer d’expulser d’Allemagne tous les migrants déjà enregistrés ailleurs dans l’UE, il n’inquiète pas que la Chancellerie à Berlin. Si cette foule doit vraiment retraverser la montagne, c’est bien évidemment en Autriche puis en Italie qu’elle aboutira. Là est le problème des slogans «populistes» et autres remèdes réputés nationaux. Sur le papier, ils sont identiques et se prêtent à de magnifiques alliances. Dans la réalité, ils sont incompatibles, sauf à fâcher les voisins et à cadenasser toutes les frontières. (…) Cynisme contre hypocrisie, Emmanuel Macron et Matteo Salvini ont vidé mardi leur aigreur à propos de l’Aquarius et des 629 clandestins repêchés au nord de la Libye. Du côté français comme du côté allemand, il apparaît que les deux semaines qui mènent au sommet vont décider si Rome penche vers l’ouest ou vers l’est. Paris admet que l’Union européenne a un problème quand l’Italie doit accueillir 80 % des migrants venus de Libye. Le chef de la diplomatie allemande, Heiko Maas, reconnaît qu’il faut se forcer «à voir la réalité à travers d’autres regards européens». L’Élysée a confirmé jeudi des pistes déjà explorées pour rendre la réalité plus supportable à des Italiens confrontés, chez eux, à des centaines de points de fixation comparables à l’ex-ghetto de migrants à Calais. Il sera donc question d’aides financières démultipliées par l’UE et de mobilisation du contingent de gardes-frontières européens. Au-delà de ces palliatifs communautaires, la France et ses voisins doivent se préparer à deux exutoires plus vigoureux s’il faut vraiment soulager l’Italie, prévient Pierre Vimont, ex-pilier du Quai d’Orsay et conseiller de l’UE durant la crise de 2015-2016. D’abord l’accueil direct des rescapés de la Méditerranée sur leur territoire, sujet jusqu’ici tabou que l’Espagne a commencé de rompre en acceptant les passagers de l’Aquarius. (…) Ensuite, l’ouverture de «centres de tri» hors de l’UE (peut-être en Albanie), ce qui permettrait d’évacuer le problème italien. (…) Mais attention, prévient l’ambassadeur Vimont, «il ne s’agit pas de s’en laver les mains. Si la question africaine n’est pas réglée dans la durée, les migrants reviendront inévitablement frapper à notre porte». Le Figaro

C’est une information qui devrait compter dans les débats bioéthiques du moment. Un sondage Ifop commandé par Alliance Vita (1) et dévoilé aujourd’hui par La Croix souligne l’importance et la singularité de la figure du père aux yeux des Français. Pour l’association, il s’agit avant tout de braquer les projecteurs sur l’un des enjeux des discussions actuelles sur l’extension de la PMA aux couples de femmes et aux femmes seules, envisagée dans le cadre de la révision des lois de bioéthique. Ainsi, 93 % des Français considèrent que les pères ont un « rôle essentiel pour les enfants », tandis que les trois quarts d’entre eux adhèrent à l’affirmation selon laquelle « les rôles du père et de la mère sont différents et complémentaires » ; et 89 % jugent que « l’absence de père, c’est quelque chose qui marque toute la vie ». (…) À un moment où la question sur la PMA polarise toutes les attentions, selon ce sondage, 61 % des Français estiment qu’« il faut privilégier le besoin de chaque enfant d’avoir un père en réservant la PMA aux couples homme-femme ayant un problème médical d’infertilité ». Mais 39 % jugent plutôt qu’« il faut privilégier le désir d’enfant en permettant la PMA sans père pour les femmes seules ou les couples de femmes ». Des chiffres qui peuvent surprendre comparés aux autres enquêtes menées par l’Ifop, notamment celles publiées dans La Croix et L’Obs en janvier, ou encore cette semaine par Ipsos pour France Télévisions. Ces enquêtes donnaient systématiquement des proportions opposées quant à l’adhésion des Français à l’extension de la PMA : 60 % y étaient favorables, 40 % étaient contre.(…) Si les Français portent un regard très majoritairement positif sur le rôle des pères, il existe cependant des différences d’approche, notamment entre les hommes qui sont pères et ceux qui ne connaissent pas l’expérience de la paternité. Ainsi 58 % des pères sont tout à fait d’accord lorsqu’on leur demande si « l’absence de père est quelque chose qui marque toute une vie ». Le chiffre tombe à 41 % pour les hommes qui n’ont pas d’enfants. Soit une différence de 17 points. Autre intervalle notable : celui qui s’établit entre les générations : 39 % des 18-24 ans estiment qu’il ne faut pas étendre la PMA, alors qu’ils sont 78 % des plus de 65 ans. « C’est la preuve qu’au fur et à mesure des générations, les références traditionnelles vont être chamboulées », estime Jérôme Fourquet. La Croix

Tout dépend de la manière dont on pose la question : si on met en avant l’ouverture d’un droit, en demandant aux Français s’ils sont pour une extension de la PMA, ils y sont majoritairement favorables. En revanche, si on présente le droit de l’enfant à avoir un père, ils sont majoritairement opposés à une évolution de la loi. (…) Quelle que soit la question, vous avez 40 % de gens qui sont favorables, 40 % d’opposés, et 20 % qui oscillent. Ce sont ces derniers qui portent la tension éthique et dont la réponse peut varier selon la façon dont la question est posée. Jérome Fourquet

On assiste aujourd’hui à un grand affaiblissement de l’image du père dans nos sociétés. C’est aussi le cas pour celle de la mère. La paternité est par nature une expérience subjective, mais je vois aujourd’hui beaucoup de couples qui, au milieu de la trentaine, hésitent à être parents. Les naissances surviennent plus tard qu’auparavant : cela montre bien que l’aventure de la paternité est devenue quelque chose d’éminemment subjectif, et donc de plus fragile. Elle n’est plus portée par la société et ne bénéficie plus d’un soutien collectif. Jacques Sédat (psychanalyste)

Le militant nationaliste britannique Tommy Robinson a été arrêté à Leeds et presque immédiatement condamné à 13 mois de prison ferme alors qu’il tentait de filmer les suspects d’un procès dont les médias locaux n’ont pas le droit de parler. Un épais voile noir n’en finit plus d’envelopper la liberté d’expression dans les démocraties occidentales. Il se montre particulièrement oppressant dès lors qu’il s’agit de museler des opinions critiques au sujet de la crise migratoire, des dangers de l’islamisme et, plus largement, du dogme multiculturaliste comme modèle supposé de société. Ces opinions critiques, si elles peuvent en choquer moralement certains, ne constituent pourtant pas des délits, ou en tout cas, pas encore… Les voies employées sont multiples et complémentaires. Sur le plan répressif, on peut mentionner les fermetures abusives et arbitraires de comptes sur les réseaux sociaux, soit par décision hautement inquisitrice des autorités facebookiennes (comme ce fut le cas par exemple pour Génération identitaire dont le compte a été récemment clos sans autre forme de procès), soit sous pression d’activistes qui, en procédant à des signalements massifs se lancent dans des sortes de fatwas numériques et finissent promptement par obtenir la fermeture des comptes qui les dérangent. On pense notamment au truculent dessinateur Marsault, mais les cas semblables sont légion. La voie judiciaire est également très utilisée pour faire taire les récalcitrants. On a pu assister par exemple à la condamnation ubuesque d’Éric Zemmour pour ce qui finit par s’apparenter, ni plus ni moins, à du délit d’opinion et à l’introduction piano sano d’un délit d’islamophobie et de blasphème dans les cours européennes. Le sort actuel de l’activiste britannique, Tommy Robinson (de son vrai nom Stephen Yaxley-Lennon), s’inscrit dans ce contexte sinistré. Le britannique de 35 ans, fondateur de l’English Defence League, hostile à l’islam radical et à la charia (ce qui peut plaire ou déplaire mais demeure une conviction de l’ordre de l’opinion et ne constitue donc pas un délit), est dans le collimateur des autorités de son pays. L’homme a été arrêté, le vendredi 25 mai, tandis qu’il diffusait une vidéo filmée en direct des abords du tribunal de Leeds où se tenait un procès mystérieux. Mystérieux car il existe une disposition du droit britannique permettant aux autorités judiciaires d’ordonner une « reporting restriction ». C’est-à-dire un embargo pendant lequel personne n’a le droit d’évoquer publiquement (journalistes inclus, donc) une affaire en cours de jugement. Cette mesure est décidée dans un but de bonne administration de la justice, de bon déroulement des procès, afin que l’émoi populaire suscité par telle ou telle affaire ne vienne pas nuire à la bonne et sereine marche d’une justice que l’on imagine naturellement impartiale, afin également d’en protéger les parties, plaignants ou accusés. Tommy Robinson, et c’est là son tort et sa limite, n’a pas souhaité se soumettre à cette curieuse loi d’airain, et s’est donc tout de même rendu au palais de justice pour y interpeller les accusés de ce qu’il a décrit comme étant supposément le procès des viols de fillettes dont les accusés sont des gangs pakistanais, notamment dans la région de Telford, exactions qui se sont produites pendant plusieurs décennies et qui ont mis un temps infini à être révélées puis prises en compte par des autorités surtout préoccupées par le risque de stigmatisation des communautés ethno-religieuses concernées, plutôt que par la protection des populations locales. Cette information sur la nature réelle du procès n’a pas pu être formellement vérifiée ni énoncée puisque, de toute façon, dans cette situation orwellienne, la presse n’est pas autorisée à en parler. Il s’agit donc ici de propos qu’on n’a pas le droit de tenir au sujet d’une affaire qu’il faut taire. Tommy Robinson a été interpellé et, dans une hallucinante et inhabituelle célérité, la justice l’a presque immédiatement condamné à une peine ferme de 13 mois de prison, sans que celui-ci n’ait pu avoir droit à un procès équitable ni consulter l’avocat de son choix. Tout ceci s’est déroulé sans que la presse n’ait vraiment le droit d’évoquer son cas, puisque les juges ont appliqué à sa condamnation une seconde « reporting restriction », sorte de couche supplémentaire dans le mille-feuille de silences et de censures nimbant déjà ce dossier décidément gênant. Au pays de l’Habeas corpus, cette affaire fait du bruit. Aussitôt, une pétition rassemblant vite plus de 500 000 signatures a circulé dans le monde entier, et l’émoi que l’on voulait mater s’est au contraire amplifié, par le biais notamment des réseaux sociaux dont on comprend bien qu’ils fassent l’objet de toutes les tentatives de restrictions et de lois liberticides à venir. Des personnalités aussi diverses que la demi-sœur de Meghan Markle ou le fils de Donald Trump, le leader néerlandais Geert Wilders, le chanteur Morrissey ou la secrétaire générale adjointe des Républicains, Valérie Boyer, et beaucoup d’autres célèbres ou anonymes, se sont émus et ont interpellé les autorités britanniques sur cette curieuse conception de la justice, expéditive pour les uns, anormalement complaisante et longue pour les autres. Des manifestants excédés ont même fini par s’en prendre à la police, samedi 9 juin, près de Trafalgar Square à Londres. Tommy Robinson se savait attendu au tournant ; il a toutefois bravé la loi en toute connaissance de cause, comme il l’avait déjà fait dans un précédent procès sur une affaire similaire, écopant alors de trois mois avec sursis, lesquels sont alors venus s’ajouter à la peine récemment prononcée pour « atteinte à l’ordre public ». On peut toutefois légitimement s’interroger sur plusieurs points qui choquent l’opinion publique ainsi que le bon sens. Tout d’abord, est-il judicieux bien que judiciaire, de la part des autorités britanniques, de décider de faire régner de nouveau le silence dans le traitement d’une affaire dans laquelle, précisément, c’est le silence complice des autorités qui est en partie mis en cause par les opinions publiques ? N’est-ce pas redoubler le mal et contribuer à rendre légitimes les soupçons d’étouffement de ces affaires pour des motifs idéologiques ? Peut-on encore parler du réel, le nommer, le montrer, sans encourir les foudres morales ni risquer l’embastillement ou le sort d’Oscar Wilde à la Reading Gaol ? Les démocraties occidentales qui se conçoivent pourtant comme « libérales » et s’opposent idéologiquement à ce qu’elles qualifient dédaigneusement de « démocraties illibérales » et populistes, ont-elles conscience de déroger, par ces silences complices et ces actions douteuses de musèlement, au libéralisme d’opinion qui fonde les régimes démocratiques et institue, normalement, les libertés fondamentales ? Ont-elles conscience de renforcer le fort soupçon de manipulation des opinions qui pèse de plus en plus sur elles, Brexit après Brexit, vote « populiste » après vote « populiste », rejet après rejet ? Ont-elles conscience que plus une censure s’applique, plus la réaction à cette censure est forte, que plus elles se conduisent ainsi, plus la colère et la révolte – qu’elles s’imaginent étouffer – grondent ? Ont-elles conscience que loin de protéger l’image des populations prétendument stigmatisées dans ces affaires, elles ne font que nourrir les interrogations et les soupçons à leur sujet ? (…) Les autorités ignorent-elles par ailleurs le sort réservé aux militants de ces mouvances hostiles à l’islam radical lorsqu’ils sont jetés ainsi en pâture dans des prisons tenues par les gangs que ces militants dénoncent précisément ? Kevin Crehan, condamné à 12 mois de prison pour avoir (certes stupidement) jeté du bacon sur une mosquée, n’a pas survécu à son incarcération. Tommy Robinson, lui-même précédemment incarcéré dans une affaire de prêt familial, a été victime de graves violences. Sa sécurité fait-elle l’objet de garanties spécifiques au vu du contexte ? Enfin, le silence gêné de certains des principaux médias sur cette affaire ne pose-t-il pas de nouveau la question du pluralisme et de la liberté d’expression réelle dans le paysage médiatique occidental ? Anne-Sophie Chazaud (Causeur)

A man who drove a van into a crowd of Muslims near a London mosque has been found guilty of murder. Darren Osborne, 48, ploughed into people in Finsbury Park in June last year, killing Makram Ali, 51, and injuring nine others. Osborne, from Cardiff, was also found guilty of attempted murder and is due to be sentenced on Friday. (…) Police later found a letter in the van written by Osborne, referring to Muslim people as « rapists » and « feral ». He also wrote that Muslim men were « preying on our children ». The trial heard Osborne became « obsessed » with Muslims in the weeks leading up to the attack, having watched the BBC drama Three Girls, about the Rochdale grooming scandal. BBC

Vous, les Blancs, vous entraînez vos filles à boire et à faire du sexe. Quand elles nous arrivent, elles sont parfaitement entraînées. Ahmed (violeur pakistanais)

Je suis une survivante du gang de Rotherham. (…) Je fais partie de la plus grande enquête jamais menée au Royaume-Uni sur les abus sexuels commis sur des enfants. Adolescente, j’ai été emmenée dans plusieurs maisons et appartements situés au-dessus de restaurants à emporter dans le nord de l’Angleterre, où j’ai été battue, torturée et violée plus d’une centaine de fois. On m’a traitée de « salope blanche » et de « c*** blanche » pendant qu’ils me battaient. Ils m’ont clairement fait comprendre que parce que je n’étais pas musulmane, que je n’étais pas vierge et que je ne m’habillais pas « modestement », ils pensaient que je méritais d’être « punie ». Ils m’ont dit que je devais « obéir » ou être battue. (…) Comme les terroristes, ils croient fermement que les crimes qu’ils commettent sont justifiés par leurs croyances religieuses. Les experts affirment que les gangs de toilettage ne sont pas les mêmes que les réseaux pédophiles. C’est quelque chose que le gouvernement central doit vraiment comprendre afin de prévenir d’autres crimes de ce type à l’avenir. En novembre 2017, le gouvernement suédois a organisé une réunion au cours de laquelle il a déclaré ce qui suit : « La violence sexuelle est utilisée comme une tactique du terrorisme », et en tant que telle, elle a été reconnue comme une menace pour la sécurité nationale de la Suède. Le lien entre le terrorisme et les viols commis par des gangs islamistes n’a pas été ignoré. Ils ont appelé à la mise en place d’une éducation à la lutte contre l’extrémisme. Cela me semble être une réponse gouvernementale équilibrée et intelligente. L’endoctrinement religieux joue un rôle important dans le processus d’implication des jeunes hommes dans la criminalité des gangs de toilettage. Les idées religieuses sur la pureté, la virginité, la modestie et l’obéissance sont poussées à l’extrême jusqu’à ce que d’horribles abus deviennent la norme. On me l’a enseigné comme un concept d' »aliénation ». « Les filles musulmanes sont bonnes et pures parce qu’elles s’habillent modestement, se couvrant jusqu’aux chevilles et aux poignets, et couvrant leur entrejambe. Elles restent vierges jusqu’au mariage. Ce sont nos filles. « Les filles blanches et les filles non musulmanes sont mauvaises parce qu’elles s’habillent comme des traînées. Vous montrez les courbes de votre corps (montrer l’écart entre vos cuisses signifie que vous le demandez) et vous êtes donc immorales. Les filles blanches couchent avec des centaines d’hommes. Vous êtes les autres filles. Vous ne valez rien et vous méritez d’être violées collectivement ». Cette hypocrisie religieuse haineuse frappe les gens au plus profond d’eux-mêmes. Mais elle est loin d’être unique. Mon principal agresseur me citait des passages du Coran tout en me battant. (…) J’ai subi des violences sexuelles et des tortures horribles, sanctionnées par la religion. Je suis donc convaincue que nous devons être conscients que l’extrémisme religieux est un phénomène potentiellement dangereux, afin de pouvoir en protéger les gens. J’ai été témoin de la façon dont les jeunes hommes sont préparés à devenir des agresseurs par des membres plus âgés de gangs de préparation. Les tactiques sont très proches de celles utilisées pour préparer les terroristes : bombance d’amour, langage émotionnel (« brother », « cuz », « blud »), promesses de richesse et de célébrité, puis humiliation, contrôle par la culpabilité et la honte, entraînement au maniement des armes, inculcation de la haine et de la peur de l’étranger. (…) En même temps, ils continuent à convaincre ces jeunes hommes qu’ils doivent aussi trouver des filles à violer. La criminalité des gangs de toilettage est soutenue par l’extrémisme religieux. À l’instar de la Suède, nous devons le reconnaître officiellement et nous efforcer de réduire les prêches extrémistes, d’enseigner des contre-récits religieux, de dispenser une éducation à l’extrémisme sexiste et d’offrir une éducation relationnelle de qualité, tout en tirant les leçons de Prevent et de Channel. Nous devons adopter une approche prudente, réfléchie et respectueuse des droits de l’homme de chacun. Victime d’un gang de toilettage à Rotherham

A l’exception d’un demandeur d’asile afghan, tous sont d’origine pakistanaise. Toutes les filles sont blanches. L’équation est aussi froide et simple qu’explosive, dans un Royaume-Uni en proie au doute sur son modèle multiculturel. (…) Dans les semaines suivant le procès, les médias égrènent les noms de villes où des gangs similaires à celui de Rochdale sont démantelés : Nelson, Oxford, Telford, High Wycombe… Et, fin octobre, c’est à nouveau à Rochdale qu’un groupe de neuf hommes est appréhendé. Chaque fois, les violeurs sont en grande majorité d’origine pakistanaise. Les micros se tendent vers les associations ou les chercheurs spécialisés dans la lutte contre les abus sexuels. Selon leurs conclusions, entre 46 % et 83 % des hommes impliqués dans ce type précis d’affaires – des viols commis en bande par des hommes qui amadouent leurs jeunes victimes en « milieu ouvert » – sont d’origine pakistanaise (les statistiques ethniques sont autorisées en Grande-Bretagne). Pour une population d’origine pakistanaise évaluée à 7 %. (…) En septembre, un rapport gouvernemental conclura à un raté sans précédent des services sociaux et de la police, qui renforce encore l’opinion dans l’idée qu’un « facteur racial » a joué dans l’affaire elle-même, mais aussi dans son traitement par les autorités : entre 2004 et 2010, 127 alertes ont été émises sur des cas d’abus sexuels sur mineurs, bon nombre concernant le groupe de Shabir Ahmed, sans qu’aucune mesure soit prise. A plusieurs reprises, les deux institutions ont estimé que des jeunes filles âgées de 12 à 17 ans « faisaient leurs propres choix de vie ». Pour Ann Cryer, ancienne députée de Keighley, une circonscription voisine, aucun doute n’est permis : police et services sociaux étaient « pétrifiés à l’idée d’être accusés de racisme ». Le ministre de la famille de l’époque, Tim Loughton, reconnaît que « le politiquement correct et les susceptibilités raciales ont constitué un problème ». L’air est d’autant plus vicié que, à l’audience, Shabir Ahmed en rajoute dans la provocation. Il traite le juge de « salope raciste » et affirme : « Mon seul crime est d’être musulman. » Un autre accusé lance : « Vous, les Blancs, vous entraînez vos filles à boire et à faire du sexe. Quand elles nous arrivent, elles sont parfaitement entraînées. » (…) un employé de la mairie s’interroge. Anonymement. « Où est la limite du racisme ? Les agresseurs voyaient ces filles comme du « déchet blanc », c’est indéniablement raciste. Mais les services sociaux, des gens bien blancs, ne les ont pas mieux considérées. » A quelques rues de là, dans sa permanence, Simon Danczuk, député travailliste de Rochdale qui a été l’un des premiers à parler publiquement d’un « facteur racial », juge tout aussi déterminant ce qu’il appelle le « facteur social » : « Les responsables des services sociaux ont pu imaginer que ces filles de même pas 15 ans se prostituaient, alors qu’ils en auraient été incapables à propos de leurs propres enfants. » (…) Mohammed Shafiq estime qu’ »une petite minorité d’hommes pakistanais voient les femmes comme des citoyens de seconde catégorie et les femmes blanches comme des citoyens de troisième catégorie ». Mais, pour lui, les jeunes filles agressées étaient surtout vulnérables. « Le fait qu’elles traînent dehors en pleine nuit, qu’elles soient habillées de façon légère, renforçait les agresseurs dans leur idée qu’elles ne valaient rien, qu’elles étaient inférieures. Mais cela faisait surtout d’elles des proies faciles, alors que les filles de la communauté pakistanaise sont mieux protégées par leur famille, et qu’un abus sexuel y est plus difficilement dissimulable. » Le Monde

Evocation juste et déchirante de la difficulté de la dénonciation de viols par des gamines de quinze ans dans le Nord de l’Angleterre, “Three Girls” est une œuvre puissante et nécessaire, inspirée de faits réels. A revoir en replay sur Arte.tv jusqu’au 21 juin 2018. Holly, 15 ans, est nouvelle dans son lycée. Elle a peu d’amis, à part deux sœurs désœuvrées qu’elle suit souvent dans un restaurant pakistanais où les employés les traitent comme des reines. Holly ne voit pas le piège qui se referme, jusqu’à ce qu’un des commerçants la viole dans l’arrière-boutique. La police ne prête pas attention à ses dires. Même ses parents doutent d’elle et ne la voient pas s’enfoncer dans l’engrenage d’un réseau de prostitution. Inspirée d’une histoire vraie, Three Girls nous plonge, avec un réalisme déchirant, dans l’horreur d’un trafic sexuel de grande ampleur, en n’éludant aucun aspect dérangeant, comme la terrible négligence des services sociaux et de la police. Une illustration supplémentaire de l’incommensurable difficulté de la dénonciation d’un viol, pour des victimes que la société juge, consciemment ou non, coupables (la retranscription des vraies paroles des avocats de la défense lors des scènes de procès est effarante). Three Girls est une œuvre formellement percutante, interprétée par des actrices formidables (Molly Windsor vient de remporter un Bafta pour le rôle de Holly). Une fois de plus, les Britanniques proposent une approche lucide et rigoureuse, quasi journalistique, de l’injustice et des défaillances de leurs institutions. Courageux et nécessaire. Télérama

Les tabloïds se sont contentés de rester en surface. Three Girls creuse en profondeur les faits et leur impact sur les victimes. Nous voulions faire entendre leurs voix, trop longtemps ignorées. Il nous a fallu trois ans pour engager le dialogue et obtenir leur confiance. Cela a été un véritable travail de mémoire, où chaque nouvelle discussion apportait son lot de détails. (…) Three Girls est aussi l’histoire d’un intolérable mépris envers les classes sociales les plus pauvres, que l’on refuse de voir et d’écouter. Les victimes de Rochdale étaient des « filles à problèmes », venant de familles avec des antécédents criminels. Elles avaient sans doute bien cherché ce qui leur arrivait…(…) C’est d’autant plus une œuvre d’utilité publique que la BBC nous a soutenus de bout en bout. La charte de la chaîne dit qu’elle doit « divertir, éduquer et informer ». Nous n’avons pas cherché à divertir, seulement à éduquer et informer. Simon Lewis

Ces filles ont vécu l’horreur avant d’être humiliées par la police et les services sociaux, qui les ont traitées de menteuses et de gamines narcissiques. Personne n’a voulu les croire quand elles ont dénoncé leurs agresseurs ! Chacun des trois épisodes de la série s’attache à montrer les ratés de la police, puis de la justice et des services sociaux. (…) Il a fallu imaginer une narration rapide, pleine d’ellipses, au risque de ne pas coller à l’ensemble des faits. Mais chaque scène, même la plus succincte, est inspirée par nos entretiens ou notre étude des archives de l’affaire. Rien n’est gratuit ni n’a été imaginé pour manipuler les émotions des téléspectateurs. (…) J’ai commencé ma carrière en réalisant des documentaires et j’ai appliqué les mêmes techniques de recherche et de mise en scène. Mais nous ne pouvions pas montrer le visage des filles et de leurs familles, révéler leur identité. Nous avons donc dû tourner un drame au plus près des faits — les scènes de tribunal respectent mot pour mot les minutes du procès —, et l’écriture fictionnelle nous a permis d’être au plus près des émotions des différents protagonistes. (…) La série a été diffusée peu de temps avant les élections générales britanniques [l’équivalent de nos législatives, ndlr], en mai 2017, et a sans doute profité de l’appétit politique du public. Plus de huit millions de téléspectateurs l’ont suivie lors de sa diffusion sur la BBC, et nous avons été assaillis de demandes pour la diffuser dans des écoles ou des centres culturels. Avec, à chaque fois, une même envie d’apprendre des erreurs qui y sont dénoncées. Philippa Lowthorpe

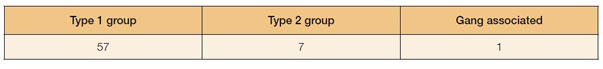

By date of conviction, we have evidence of such exploitation taking place in Keighley (2005 and 2013), Blackpool (2006), Oldham (2007 and 2008), Blackburn (2007, 2008 and 2009), Sheffield (2008), Manchester (2008 and 2013) Skipton (2009), Rochdale (two cases in 2010, one in 2012 and another in 2013), Nelson (2010), Preston (2010) Rotherham (2010) Derby (2010), Telford (2012), Bradford (2012), Ipswich (2013), Birmingham (2013), Oxford (2013), Barking (2013) and Peterborough (2013). This is based on a trawl of news sources so is almost certainly incomplete. (…) Ceop data about the ethnicity of offenders and suspects identified by those 31 police forces in 2012 is incomplete. The unit says: “All ethnicities were represented in the sample. However, a disproportionate number of offenders were reported as Asian.” Of 52 groups where ethnicity data was provided, 26 (50 per cent) comprised all Asian offenders, 11 (21 per cent) were all white, 9 (17 per cent) groups had offenders from multiple ethnicities, 4 (8 per cent) were all black offenders and there were 2 (4 per cent) exclusively Arab groups. Of the 306 offenders whose ethnicity was noted, 75 per cent were categorised as Asian, 17 per cent white, and the remaining 8 per cent black (5 per cent) or Arab (3 per cent). By contrast, the seven “Type 2 groups” – paedophile rings rather than grooming gangs – “were reported as exclusively of white ethnicity”. Ceop identified 144 victims of the Type 1 groups. Again, the data was incomplete. Gender was mentioned in 118 cases. All were female. Some 97 per cent of victims were white. Girls aged between 14 and 15 accounted for 57 per cent of victims. Out of 144 girls, 100 had “at least one identifiable vulnerability” like alcohol or drug problems, mental health issues or a history of going missing. More than half of the victims were in local authority care. The 27 court cases that we found led to the convictions of 92 men. Some 79 (87 per cent) were reported as being of South Asian Muslim origin. Three were white Britons, two were Indian, three were Iraqi Kurds, four were eastern European Roma and one was a Congolese refugee, according to reports of the trials. Considerable caution is needed when looking at these numbers, as our sample is very unscientific. There are grooming cases we will have missed, and there will undoubtedly be offences that have not resulted in convictions. (…) Ceop says: “The comparative levels of freedom that white British children enjoy in comparison to some other ethnicities may make them more vulnerable to exploitation. “They may also be more likely to report abuse. This is an area requiring better data and further research.” Channel 4 news

Child sexual exploitation is one of the most sickening crimes of our age, yet the scale is unknown because, by its very nature, boys and girls frequently go missing in an underworld of systematic abuse. Barnardo’s has 22 projects across the country dedicated to finding and helping these young people, and has been campaigning for years to bring the issue to the forefront of the government’s agenda. The past weeks have seen a welcome shift in recognition of this problem, but the focus has been on the ethnicity of abusers, based on two high-profile cases in particular parts of England. It’s crucial to recognise that just as the ethnicity of the perpetrators differs across the UK, so does that of the children. We need to pull away from the growing stereotypes: it is not just Asian men who commit this crime, nor are the victims only white – black and Asian girls are targeted too. They are used like puppets by these abhorrent men and women – groomed and manipulated to a point where they are brainwashed, raped and scarred for life. I have met some very brave girls and boys who we are helping to overcome the tragic childhood that they will never get back. One of them is Aaliyah. Her story isn’t unusual. As 14 she began to become estranged from her parents and started to go out a lot. She was introduced to men older than her, who would impress her with their flash cars and gifts. Desperate for love and attention the affection they showed her seemed very real, until it turned nasty. The unthinkable cruelty she suffered will never be forgotten – Aaliyah was physically and mentally abused, with one so-called boyfriend pulling her out of his car by her hair and threatening to cut her legs off with an axe before driving her to a hotel room, « to have his friends come over and do what they wanted to me ». We worked with more than a thousand children and young people like Aaliyah last year, and we believe that is likely to be the tip of the iceberg. Wherever we have looked for exploitation, we have found it. We need to use the momentum of current debate to highlight what really matters: protecting these vulnerable children. It is 16 years since Barnardo’s opened its first service dedicated to sexually exploited children in Bradford. Today we release a report, Puppet on a String, that highlights three new issues: trafficking around the UK is becoming more common; sexual exploitation is more organised and grooming more sophisticated, with technology being used to find, isolate and control victims; and increasingly younger children are being abused. Emma’s sexual exploitation began in a similar way to Aaliyah’s. When, aged 14, she met a man in his early 30s who showered her with gifts and attention, she fell in love, but soon her « boyfriend » began abusing her and forcing her to sleep with different men. Her words are heartbreaking: « I just hoped that one day one of the men would be a real boyfriend, that he’d like me for the real me and that he’d want to save me. But it never happened. » Anne-Marie Carrie

Tout le monde connaît désormais l’affaire des huit hommes condamnés pour avoir ramassé des mineures vulnérables dans la rue, les avoir abreuvées de boissons et de drogues avant d’avoir des relations sexuelles avec elles. Une histoire choquante. Mais peut-être n’en avez-vous pas entendu parler. Car ces agressions sexuelles n’ont pas eu lieu à Rochdale, où une histoire similaire a défrayé la chronique pendant des jours en mai, mais à Derby, au début du mois. Quinze filles âgées de 13 à 15 ans, dont beaucoup étaient placées, ont été la proie de ces hommes. Bien qu’ils ne travaillent pas en bande, leurs méthodes sont similaires : ils ciblent souvent les enfants placés et les attirent avec, entre autres, des peluches. Mais cette fois, sur les huit prédateurs, sept étaient blancs et non asiatiques. L’affaire n’a guère fait de vagues dans les médias nationaux. Parmi les quotidiens, seuls le Guardian et le Times en ont parlé. Il n’y a eu aucun commentaire sur la façon dont ces crimes mettent en lumière la culture britannique, ou sur la façon dont les hommes blancs d’âge moyen doivent affronter les failles profondes de leur identité religieuse et ethnique. Pourtant, c’est exactement ce qui s’est passé après la condamnation, en mai, du « gang sexuel asiatique » de Rochdale, qui a fait la une de tous les journaux nationaux. Bien que l’analyse de l’affaire se soit concentrée sur l’importance du facteur racial, religieux et culturel, l’histoire non rapportée est celle de la façon dont les politiciens et les médias ont créé un nouveau bouc émissaire racial. En fait, si quelqu’un veut étudier comment le racisme commence et s’insinue dans la conscience d’une nation entière, il n’a pas besoin de chercher plus loin. (…) l’intérêt intense pour l’histoire de Rochdale est né d’un » scoop » du Times de janvier 2011 qui se basait sur la condamnation d’au plus 50 Pakistanais britanniques sur une population totale de 1,2 million d’habitants au Royaume-Uni, soit un sur 24 000 (…) Même le Child Protection and Online Protection Centre (Ceop), qui a également étudié les délinquants potentiels qui n’ont pas été condamnés, n’a identifié que 41 gangs asiatiques (sur 230 au total) et 240 individus asiatiques – et ils sont dispersés dans tout le pays. Malgré cela, un nouveau stéréotype s’est installé : une proportion importante d’hommes asiatiques sont des « groomers » (et le reste de leurs communautés le savent et se taisent). Mais s’il s’agit vraiment d’un phénomène « asiatique », comment se fait-il que les Indiens ne le fassent pas ? Si c’est une affaire » pakistanaise « , comment se fait-il qu’un Afghan ait été condamné dans l’affaire de Rochdale ? Et s’il s’agit d’une affaire » musulmane « , comment se fait-il que personne d’origine africaine ou moyen-orientale ne soit impliqué ? La réponse habituelle à tous ceux qui s’interrogent à ce sujet est : regardez les faits en face, toutes les personnes condamnées à Rochdale étaient musulmanes. Si un seul cas suffit pour faire une telle généralisation, qu’en serait-il si tous les membres d’une bande de voleurs à main armée étaient blancs, ou si les cybercriminels ou les trafiquants d’enfants étaient blancs ? (Serions-nous si désireux de « regarder les choses en face » et d’en faire un problème auquel l’ensemble de la communauté blanche doit faire face ? Aurions-nous des articles examinant ce qui, dans l’appartenance à la Grande-Bretagne, au christianisme ou à l’Europe, rend les gens si capables de telles choses ? (…) Quoi qu’il en soit, nous savons que l’abus de jeunes filles blanches n’est pas un problème culturel ou religieux, car il n’existe pas d’antécédents historiques en Asie ou dans le monde musulman. Comment des hommes asiatiques d’âge moyen, issus de communautés très unies, ont-ils pu entrer en contact avec des adolescentes blanches à Rochdale ? Le principal intérêt culturel de cette histoire est que les jeunes filles vulnérables, souvent perturbées, qui sortent régulièrement tard le soir, se retrouvent souvent dans des restaurants qui ferment tard et dans des bureaux de minicars, dont le personnel est presque exclusivement composé d’hommes. Au bout d’un certain temps, des relations se nouent, les hommes offrant gratuitement des ascenseurs et/ou de la nourriture. Pour ceux qui ont un instinct de prédateur, l’exploitation sexuelle est une étape facile à franchir. Il s’agit de savoir ce que les hommes peuvent faire lorsqu’ils sont éloignés de leur famille et qu’ils sont en position de force face à des jeunes gens malmenés. C’est une histoire qui se répète dans toute la Grande-Bretagne, chez les Blancs comme chez les autres groupes ethniques : lorsque l’occasion se présente, certains hommes en profitent. La méthode précise, et le fait qu’il s’agisse d’un crime individuel ou collectif, dépendent du contexte particulier – qu’il s’agisse de prêtres, d’animateurs de jeunesse ou de réseaux sur le web. (…) si les rôles étaient inversés et que les victimes étaient asiatiques ou musulmanes, nous aurions eu droit à des commentaires d’experts tout aussi biaisés, demandant : qu’est-ce qui ne va pas dans la façon dont les musulmans élèvent les filles ? Pourquoi sont-elles si nombreuses à se retrouver dans les rues la nuit ? La communauté ne devrait-elle pas faire face à son effondrement moral choquant ? (…) Nous sommes déjà passés par là, bien sûr : dans les années 1950, les hommes antillais ont été qualifiés de proxénètes, d’espions et de criminels. Joseph Harker

In May 2012, nine men from the Rochdale area of Manchester were found guilty of sexually exploiting a number of underage girls. Media reporting on the trial focused on the fact that eight of the men were of Pakistani descent, while all the girls were white. Framing similar cases in Preston, Rotherham, Derby, Shropshire, Oxford, Telford and Middlesbrough as ethnically motivated, the media incited moral panic over South Asian grooming gangs preying on white girls. While these cases shed light on the broader problem of sexual exploitation in Britain, they also reveal continuing misconceptions that stereotype South Asian men as ‘natural’ perpetrators of these crimes due to culturally-specific notions of hegemonic masculinity. Examining newspaper coverage from 2012 to 2013, this article discusses the discourse of the British media’s portrayal of South Asian men as perpetrators of sexual violence against white victims, inadvertently construing ‘South Asian men’ as ‘folk devils’. Aisha K Gill (University of Roehampton) and Karen Harrison (University of Hull)

In more inflammatory terms, the Mail Online referred to the perpetrators as a ‘small minority who see women as second class citizens, and white women probably as third class citizens’ (Dewsbury 2012) Aisha K Gill (University of Roehampton) and Karen Harrison (University of Hull)

Il existe une petite minorité d’hommes pakistanais qui pensent que les filles blanches sont des proies faciles. Et nous devons être prêts à l’admettre. On ne peut commencer à résoudre un problème que si on le reconnaît d’abord. Cette petite minorité qui considère les femmes comme des citoyennes de seconde zone, et les femmes blanches probablement comme des citoyennes de troisième zone, doit être dénoncée. (…) Il s’agissait d’hommes adultes, dont certains étaient des enseignants religieux ou des chefs d’entreprise, avec de jeunes familles. Que ces filles soient ou non des proies faciles, ils savaient que c’était mal. (…) Mosquée après mosquée, cette question devrait être soulevée afin que toute personne impliquée de près ou de loin commence à sentir que la communauté se retourne contre elle. Les communautés ont la responsabilité de se lever et de dire : « C’est mal, cela ne sera pas toléré ». (…) La sensibilité culturelle ne devrait jamais être un obstacle à l’application de la loi. (…) Si l’on ne fait pas preuve « d’ouverture et de franchise », cela « créera un vide que les extrémistes pourront combler, un vide où la haine pourra être colportée ». (…) Le leadership consiste à amener les gens avec soi, et pas seulement à les énerver. Baroness Warsi

La terrible histoire du réseau pédophile d’Oxford a jeté l’opprobre non seulement sur la ville aux clochers rêveurs, mais aussi sur la communauté musulmane locale. C’est un sentiment de répulsion et d’indignation que je ressens particulièrement, en tant que responsable musulman et imam dans ce quartier et en essayant de promouvoir une véritable intégration culturelle. (…) Mais au-delà de sa dépravation pure et simple, ce qui me déprime également dans cette affaire, c’est le refus généralisé de faire face à ses dures réalités. Le fait est que les activités vicieuses du réseau d’Oxford sont liées à la religion et à la race : la religion, parce que tous les auteurs, bien que de nationalités différentes, étaient musulmans ; et la race, parce qu’ils ciblaient délibérément des jeunes filles blanches vulnérables, qu’ils semblaient considérer comme de la « viande facile », pour utiliser l’une de leurs expressions racistes révélatrices. En effet, l’une des victimes qui a courageusement témoigné devant le tribunal a déclaré par la suite à un journal que « les hommes voulaient exclusivement des filles blanches à abuser ». Mais comme c’est souvent le cas dans la Grande-Bretagne moderne, craintive et politiquement correcte, il y a un refus crapuleux de faire face à cette réalité. Les commentateurs et les hommes politiques la contournent sur la pointe des pieds, en se cachant derrière des mots vagues. On nous dit que les abus sexuels sur les enfants se produisent « dans toutes les communautés », que les hommes blancs sont en réalité beaucoup plus susceptibles d’être des agresseurs, comme l’ont montré les retombées de l’affaire Jimmy Savile. Un commentaire particulièrement malavisé affirmait que la religion des prédateurs n’avait aucune importance, car ce qui comptait vraiment, c’était que la plupart d’entre eux travaillaient. Un commentaire particulièrement malavisé affirmait que la religion des prédateurs n’avait aucune importance, car ce qui comptait vraiment, c’était que la plupart d’entre eux travaillaient dans l’économie nocturne en tant que chauffeurs de taxi, tout comme dans le scandale sexuel de Rochdale, de nombreux abuseurs travaillaient dans des kebabs, ce qui leur donnait beaucoup plus d’occasions de cibler des jeunes filles vulnérables. Mais tout cela n’est qu’un tissu d’illusions. S’il est vrai, bien sûr, que les abus se produisent dans toutes les communautés, aucun obscurcissement ne peut cacher le schéma qui a été mis en évidence dans une série de scandales récents qui font froid dans le dos, de Rochdale à Oxford, et de Telford à Derby. Dans tous ces cas, les agresseurs étaient des hommes musulmans et leurs cibles des jeunes filles blanches mineures. En outre, des études fiables montrent qu’environ 26 % des personnes impliquées dans les réseaux de toilettage et d’exploitation sont musulmanes, soit environ cinq fois plus que la proportion de musulmans dans la population masculine adulte. Prétendre qu’il ne s’agit pas d’un problème pour la communauté islamique, c’est tomber dans le déni idéologique. Mais si ce scandale a eu lieu, c’est en partie à cause de cette pensée politiquement correcte. Toutes les agences de l’État, y compris la police, les services sociaux et le système de soins, semblaient désireuses d’ignorer l’exploitation écœurante qui se déroulait sous leurs yeux. Terrifiés à l’idée d’être accusés de racisme, désespérés de ne pas ébranler le credo officiel de la diversité culturelle, ils n’ont pris aucune mesure contre les abus évidents. (…) Étonnamment, les responsables des autorités locales semblent avoir autorisé les prédateurs à aller et venir dans les foyers d’accueil, choisissant leurs cibles pour les abreuver de boissons et de drogues avant d’abuser d’elles. Vous pouvez être sûr que si la situation avait été inversée, avec des bandes de jeunes hommes blancs et durs s’attaquant à des jeunes filles musulmanes vulnérables, les agences de l’État auraient agi avec plus d’empressement. Un autre signe de l’approche lâche de ces horreurs est la référence constante aux criminels en tant qu' »Asiatiques » plutôt que « Musulmans ». Dans ce contexte, le terme « asiatique » est totalement dénué de sens. Ces hommes ne venaient ni de Chine, ni d’Inde, ni du Sri Lanka, ni même du Bangladesh. Ils étaient tous originaires du Pakistan ou de l’Érythrée, qui se trouve en fait en Afrique de l’Est plutôt qu’en Asie. Ce qui les unissait, c’était leur mentalité tordue et corrompue, qui alimentait leur misogynie et leur racisme. (…) Dans l’orthodoxie erronée qui prévaut aujourd’hui dans de nombreuses mosquées, dont plusieurs à Oxford, on enseigne malheureusement aux hommes que les femmes sont des citoyens de seconde zone, un peu plus que des biens meubles ou des possessions sur lesquels ils ont une autorité absolue. C’est pourquoi nous constatons cette mode croissante et répréhensible de la ségrégation lors des événements islamiques sur les campus universitaires, les étudiantes musulmanes étant repoussées à l’arrière des amphithéâtres. Un incident révélateur s’est produit au cours du procès, lorsqu’il est apparu que l’un des voyous avait chauffé du métal pour marquer une jeune fille, comme s’il s’agissait d’une vache. Maintenant, si tu as des relations sexuelles avec quelqu’un d’autre, il saura que tu m’appartiens ». Dr. Taj Hargey (Imam de la Congregation islamique d’Oxford)

Attention: un entrainement peut en cacher un autre !

Au lendemain de la diffusion sur Arte, un an après la Grande-Bretagne, de la mini-série britannique Three girls …

Sur la découverte, contre les services de la police et des services sociaux, d’un trafic sexuel de jeunes mineures par notamment des réseaux d’origine pakistanaise qui a touché pendant des années une dizaine de villes britanniques …

A l’heure où les peuples européens commencent à se rebiffer contre la folie tant immigrationniste que « sociétale » que prétendent leur imposer à coup de sondages ventriloques des dirigeants eux-mêmes protégés des conséquences de leurs décisions …

Pendant qu’entre nos écrans, nos scènes musicales et les téléphones portables de nos jeunes, l’on rivalise de vulgarité et d’irrespect y compris pour les morts …

Comment ne pas voir une nouvelle illustration de ce politiquement correct …

Qui oubliant étrangement certaines victimes six mois à peine après le mouvement Me-too ..

Va jusqu’à nier l’évidence contre les membres mêmes de ces communautés les plus lucides comme la baronesse Warsi ou l’imam d’Oxford Taj Hargey …

A savoir l’existence et la sur-représentation d’une partie des immigrés pakistanais et donc musulmans qui, sourates du Coran à l’appui, considèrent les femmes et les filles blanches comme des « proies faciles » et des « citoyennes de 3e zone » …

Mais aussi contre le discours déligitimateur de nos sociologues maitres ès « paniques morales » qui à force de crier au loup finissent par produire les passages à l’acte mêmes des individus ou des groupes qu’ils dénoncent …

La dimension éminemment salutaire de ce sursaut de lucidité …

Face tant à la conjonction de la désagrégation des familles blanches les plus fragilisées et de l’indéniable radicalisation des prêches de certains imams …

Qu’à cette perversion de la démocratie qui voudrait, entre deux distributions de préservatifs et bientôt de godemichés (pardon: de « sex toys » !) à des gamines de 11 ans …

Imposer « au plus grand nombre », selon le mot d’Henry Berque, les « vices de quelques-uns » ?

Entretien

“Three Girls”, une série qui révèle “l’intolérable mépris envers les classes les plus pauvres”

Pierre Langlais

Télérama

14/06/2018

Police, justice, services sociaux: une minisérie de la BBC revient sur l’inaction des institutions britanniques dans l’affaire des adolescentes de Rochdale, victimes de trafic sexuel. Fruit d’un minutieux “travail de mémoire”, elle a contribué à libérer la parole outre-Manche.

Entre 2008 et 2010, quarante-sept adolescentes, pour les plus jeunes âgées d’à peine 13 ans, ont été victimes d’un réseau de trafic sexuel à Rochdale, dans la banlieue de Manchester, dans le nord de l’Angleterre. Three Girls, minisérie de la BBC en trois épisodes, reconstitue le calvaire de trois d’entre elles dans un drame bouleversant, rigoureusement documenté. Une œuvre filmée à hauteur de ses jeunes héroïnes, doublée d’une dénonciation puissante des injustices sociales et des ratés institutionnels que l’affaire révéla, comme l’expliquent sa réalisatrice, Philippa Lowthorpe, et son producteur, Simon Lewis (1).

La presse britannique a largement relaté cette affaire à l’époque des faits. Qu’aviez-vous à ajouter ?

Simon Lewis : Les tabloïds se sont contentés de rester en surface. Three Girls creuse en profondeur les faits et leur impact sur les victimes. Nous voulions faire entendre leurs voix, trop longtemps ignorées. Il nous a fallu trois ans pour engager le dialogue et obtenir leur confiance. Cela a été un véritable travail de mémoire, où chaque nouvelle discussion apportait son lot de détails.

C’est aussi l’histoire d’un terrible manquement des institutions…

Philippa Lowthorpe : Ces filles ont vécu l’horreur avant d’être humiliées par la police et les services sociaux, qui les ont traitées de menteuses et de gamines narcissiques. Personne n’a voulu les croire quand elles ont dénoncé leurs agresseurs ! Chacun des trois épisodes de la série s’attache à montrer les ratés de la police, puis de la justice et des services sociaux.

S.L. : Three Girls est aussi l’histoire d’un intolérable mépris envers les classes sociales les plus pauvres, que l’on refuse de voir et d’écouter. Les victimes de Rochdale étaient des « filles à problèmes », venant de familles avec des antécédents criminels. Elles avaient sans doute bien cherché ce qui leur arrivait…

Comment condenser en trois heures une affaire qui a duré cinq ans [le procès a eu lieu en 2012, ndlr] ?

P.L. : Il a fallu imaginer une narration rapide, pleine d’ellipses, au risque de ne pas coller à l’ensemble des faits. Mais chaque scène, même la plus succincte, est inspirée par nos entretiens ou notre étude des archives de l’affaire. Rien n’est gratuit ni n’a été imaginé pour manipuler les émotions des téléspectateurs.

Dans ce cas, pourquoi ne pas avoir choisi la forme documentaire ?