La prédiction est un art bien difficile, surtout en ce qui concerne l’avenir. Niels Bohr

Soudain, Norman se sentit fier. Tout s’imposait à lui, avec force. Il était fier. Dans ce monde imparfait, les citoyens souverains de la première et de la plus grande Démocratie Electronique avaient, par l’intermédiaire de Norman Muller (par lui), exercé une fois de plus leur libre et inaliénable droit de vote. Le Votant (Isaac Asimov, 1955)

Vous allez dans certaines petites villes de Pennsylvanie où, comme ans beaucoup de petites villes du Middle West, les emplois ont disparu depuis maintenant 25 ans et n’ont été remplacés par rien d’autre (…) Et il n’est pas surprenant qu’ils deviennent pleins d’amertume, qu’ils s’accrochent aux armes à feu ou à la religion, ou à leur antipathie pour ceux qui ne sont pas comme eux, ou encore à un sentiment d’hostilité envers les immigrants. Barack Obama (2008)

Pour généraliser, en gros, vous pouvez placer la moitié des partisans de Trump dans ce que j’appelle le panier des pitoyables. Les racistes, sexistes, homophobes, xénophobes, islamophobes. A vous de choisir. Hillary Clinton

I continue to believe Mr. Trump will not be president. And the reason is that I have a lot of faith in the American people. Being president is a serious job. It’s not hosting a talk show, or a reality show. The American people are pretty sensible, and I think they’ll make a sensible choice in the end. It’s not promotion, it’s not marketing. It’s hard. And a lot of people count on us getting it right. Barack Hussein Obama (Feb. 2016)

Comme je l’ai dit depuis le début, notre campagne n’en était pas simplement une, mais plutôt un grand mouvement incroyable, composé de millions d’hommes et de femmes qui travaillent dur, qui aiment leur pays, et qui veulent un avenir plus prospère et plus radieux pour eux-mêmes et leur famille. C’est un mouvement composé d’Américains de toutes races, de toutes religions, de toutes origines, qui veulent et attendent que le gouvernement serve le peuple. Ce gouvernement servira le peuple. J’ai passé toute ma vie dans le monde des affaires et j’ai observé le potentiel des projets et des personnes partout dans le monde. Aujourd’hui, c’est ce que je veux faire pour notre pays. Il y a un potentiel énorme, je connais bien notre pays, il y a potentiel incroyable, ce sera magnifique. Chaque Américain aura l’opportunité de vivre pleinement son potentiel. Ces hommes et ces femmes oubliés de notre pays, ces personnes ne seront plus oubliées. Donald Trump

Je suis désolé d’être le porteur de mauvaises nouvelles, mais je crois avoir été assez clair l’été dernier lorsque j’ai affirmé que Donald Trump serait le candidat républicain à la présidence des États-Unis. Cette fois, j’ai des nouvelles encore pires à vous annoncer: Donald J. Trump va remporter l’élection du mois de novembre. Ce clown à temps partiel et sociopathe à temps plein va devenir notre prochain président. (…) Jamais de toute ma vie n’ai-je autant voulu me tromper. (…) Voici 5 raisons pour lesquelles Trump va gagner : 1. Le poids électoral du Midwest, ou le Brexit de la Ceinture de rouille 2. Le dernier tour de piste des Hommes blancs en colère 3. Hillary est un problème en elle-même 4. Les partisans désabusés de Bernie Sanders 5. L’effet Jesse Ventura. Michael Moore

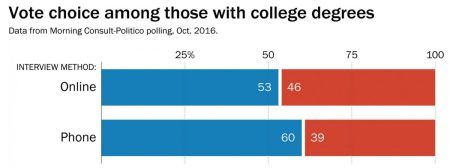

The phenomenon of voters telling pollsters what they think they want to hear, however, actually has a name: the Bradley Effect, a well-studied political phenomenon. In 1982, poll after poll showed Tom Bradley, Los Angeles’ first black mayor and a Democrat, with a solid lead over George Deukmejian, a white Republican, in the California gubernatorial race. Instead, Bradley narrowly lost to Deukmejian, a stunning upset that led experts to wonder how the polls got it wrong. Pollsters, and some political scientists, later concluded that voters didn’t want to say they were voting against Bradley, who would have been the nation’s first popularly-elected African-American governor, because they didn’t want to appear to be racist. (…) In December, a Morning Consult poll examined whether Trump supporters were more likely to say they supported him in online polls than in polls conducted by live questioners. Their finding was surprising: « Trump performs about six percentage points better online than via live telephone interviewing, » according to the study. At the same time, « his advantage online is driven by adults with higher levels of education, » the study says, countering data showing Trump’s bedrock support comes from voters without college degrees. « Importantly, the differences between online and live telephone [surveys] persist even when examining only highly engaged, likely voters. » But Galston says while the study examines « a legitimate question, » the methodology is unclear, and « it’s really important to compare apples to apples. You need to be sure that the online community has the same demographic profile » as phone polling. « It may also be the case that people who are online and willing to participate in that study are already, in effect, a self-selected sample » of pro-Trump voters, Galston says. (…) Ultimately, Trump’s claim « is more of a way to try to explain poor polling numbers. Trump is losing at the moment and he’s trying to explain it off, » Skelley says. « This doesn’t really hold up under scrutiny. » US News & world report (July 2016)

Ever since the ascendency of their “war room,” the Clinton-inspired Left has attacked the integrity and morality of all Republican presidential candidates: McCain was rendered a near-senile coot, confused about the extent of his wife’s wealth and the number of their estates. No finer man ran for president than Mitt Romney. And by November 2012 when he lost, he had been reduced to a bullying hazer in his teen-age years, a vulture capitalist, a heartless plutocrat who was rude to his garbage man, tortured dogs, had an elevator in his house, and provided horses and stables to his aristocratic wife. All were either lies or exaggerations or irrelevant and all insidiously cemented the picture of the gentlemanly Romney as a preppie, out-of-touch, old white-guy snob, and gratuitously cruel to the less fortunate. Trump was certainly more vulgar than either McCain or Romney, but what voters he lost owing to his crass candor he may well have gained back through his slash-and-burn, take-no-prisoners willingness to fight back against the liberal smear machine. We can envision what Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, or Ted Cruz would look like after six months of “going high” from the Clinton-campaign treatment. It is a mistake to believe that any other candidate would have better dealt with the Clinton-Podesta hit teams; all we can assume is that most would have suffered far more nobly than Trump. It would be wonderful if a Republican candidate ran with Romney’s personal integrity, Rubio’s charisma, Walker’s hands-on experience, Cruz’s commitment to constitutional conservatism, and Trump’s energy, animal cunning, and ferocity, but unfortunately such multifaceted candidates are rare. Victor Davis Hanson

What I was hearing was this general sense of being on the short end of the stick. Rural people felt like they’re not getting their fair share. (…) First, people felt that they were not getting their fair share of decision-making power. For example, people would say: All the decisions are made in Madison and Milwaukee and nobody’s listening to us. Nobody’s paying attention, nobody’s coming out here and asking us what we think. Decisions are made in the cities, and we have to abide by them. Second, people would complain that they weren’t getting their fair share of stuff, that they weren’t getting their fair share of public resources. That often came up in perceptions of taxation. People had this sense that all the money is sucked in by Madison, but never spent on places like theirs. And third, people felt that they weren’t getting respect. They would say: The real kicker is that people in the city don’t understand us. They don’t understand what rural life is like, what’s important to us and what challenges that we’re facing. They think we’re a bunch of redneck racists. So it’s all three of these things — the power, the money, the respect. People are feeling like they’re not getting their fair share of any of that. (…) It’s been this slow burn. Resentment is like that. It builds and builds and builds until something happens. Some confluence of things makes people notice: I am so pissed off. I am really the victim of injustice here. (…) Then, I also think that having our first African American president is part of the mix, too. (…) when the health-care debate ramped up, once he was in office and became very, very partisan, I think people took partisan sides. (…) It’s not just resentment toward people of color. It’s resentment toward elites, city people. (…) Of course [some of this resentment] is about race, but it’s also very much about the actual lived conditions that people are experiencing. We do need to pay attention to both. As the work that you did on mortality rates shows, it’s not just about dollars. People are experiencing a decline in prosperity, and that’s real. The other really important element here is people’s perceptions. Surveys show that it may not actually be the case that Trump supporters themselves are doing less well — but they live in places where it’s reasonable for them to conclude that people like them are struggling. Support for Trump is rooted in reality in some respects — in people’s actual economic struggles, and the actual increases in mortality. But it’s the perceptions that people have about their reality are the key driving force here. (…) One of the key stories in our political culture has been the American Dream — the sense that if you work hard, you will get ahead. (…) But here’s where having Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump running alongside one another for a while was so interesting. I think the support for Sanders represented a different interpretation of the problem. For Sanders supporters, the problem is not that other population groups are getting more than their fair share, but that the government isn’t doing enough to intervene here and right a ship that’s headed in the wrong direction. (…) There is definitely some misinformation, some misunderstandings. But we all do that thing of encountering information and interpreting it in a way that supports our own predispositions. Recent studies in political science have shown that it’s actually those of us who think of ourselves as the most politically sophisticated, the most educated, who do it more than others. So I really resist this characterization of Trump supporters as ignorant. There’s just more and more of a recognition that politics for people is not — and this is going to sound awful, but — it’s not about facts and policies. It’s so much about identities, people forming ideas about the kind of person they are and the kind of people others are. Who am I for, and who am I against? Policy is part of that, but policy is not the driver of these judgments. There are assessments of, is this someone like me? Is this someone who gets someone like me? (…) All of us, even well-educated, politically sophisticated people interpret facts through our own perspectives, our sense of what who we are, our own identities. I don’t think that what you do is give people more information. Because they are going to interpret it through the perspectives they already have. People are only going to absorb facts when they’re communicated from a source that they respect, from a source who they perceive has respect for people like them. And so whenever a liberal calls out Trump supporters as ignorant or fooled or misinformed, that does absolutely nothing to convey the facts that the liberal is trying to convey. Katherine Cramer

Traditional political polling in America has been living on borrowed time, and the divergence of the actual votes in Tuesday’s election from what was expected in the polls may signal that its time is up. The fact that the polls apparently missed the preferences of a large portion of the American electorate indicates a larger, more systematic issue, one that’s unlikely to be fixed anytime soon. The basic problem — and the reason pollsters have been nervous about just this sort of large-scale polling failure — comes from the low response rates that have plagued even the best polls since the widespread use of caller ID technology. Caller ID, more than any other single factor, means that fewer Americans pick up the phone when a pollster calls. That means it takes more calls for a poll to reach enough respondents to make a valid sample, but it also means that Americans are screening themselves before they pick up the phone. So even as our ability to analyze data has gotten better and better, thanks to advanced computing and an increase in the amount of data available to analysts, our ability to collect data has gotten worse. And if the inputs are bad, the analysis won’t be any good either. That self-screening is enormously problematic for pollsters. A sample is only valid to the extent that the individuals reached are a random sample of the overall population of interest. It’s not at all problematic for some people to refuse to pick up the phone, as long as their refusal is driven by a random process. If it’s random, the people who do pick up the phone will still be a representative sample of the overall population, and the pollster will just have to make more calls. Similarly, it’s not a serious problem for pollsters if people refuse to answer the phone according to known characteristics. For instance, pollsters know that African-Americans are less likely to answer a survey than white Americans and that men are less likely to pick up the phone than women. Thanks to the U.S. Census, we know what proportion of these groups are supposed to be in our sample, so when the proportion of men, or African-Americans, falls short in the sample, pollsters can make use of weighting techniques to correct for the shortfall. The real problem comes when potential respondents to a poll are systematically refusing to pick up the phone according to characteristics that pollsters aren’t measuring or can’t adjust to match what’s in the population. (…) None of this would be a problem if response rates were at the levels they were at in the 1980s, or even the 1990s. But with response rates to modern telephone polls languishing below 15%, it becomes harder and harder to determine whether systematic nonresponse problems are even happening. These problems go from nagging to consequential when the characteristics that are leading people to exclude themselves from polls are correlated with the major outcome that the poll is trying to measure. For instance, if Donald Trump voters were more likely to decide not to participate in polls because they’re rigged, and did so in a way that wasn’t correlated with known characteristics like race and gender, pollsters would have no way of knowing. Of course, if unobserved nonresponse is driving poll errors, it’s necessary to ask how polls have done so well up to this point. After all, response rates have been similarly low in at least the last four presidential elections, and the polls did well enough in those. Part of the problem, and what makes this election different, is a seeming failure of likely voter models. One of the most difficult tasks facing any election pollster is determining who is and is not actually going to vote on Election Day. People tend to say they’re going to vote even when they won’t, so it’s necessary to ask more questions. Every major pollster has their own set of questions in the likely voter questions, but they typically include items about interest in the election, past vote behavior, and knowledge of where a polling place is. Using these questions to determine who is and is not going to vote is a tricky business; the failure of a complex likely voter model is why Gallup got out of the election forecasting business. (…) It may be the case that standard sampling and weighting techniques are able to correct for sampling problems in a normal election — one in which voter turnout patterns remain predictable — but fail when the polls are missing portions of the electorate who are likely to turn out in one election but not in previous ones. Imagine that there’s a group of voters who don’t generally vote and are systematically less likely to respond to a survey. So long as they continue to not vote, there isn’t a problem. But if a candidate activates these voters, the polls will systematically underestimate support for the candidate. That seems to be what happened Tuesday night. (…) At least for unusual elections, polling seems broken — and we have no way of knowing which elections are unusual until the votes actually come in. Dan Cassino

Ce qui est nouveau, c’est d’abord que la bourgeoisie a le visage de l’ouverture et de la bienveillance. Elle a trouvé un truc génial : plutôt que de parler de « loi du marché », elle dit « société ouverte », « ouverture à l’Autre » et liberté de choisir… Les Rougon-Macquart sont déguisés en hipsters. Ils sont tous très cools, ils aiment l’Autre. Mieux : ils ne cessent de critiquer le système, « la finance », les « paradis fiscaux ». On appelle cela la rebellocratie. C’est un discours imparable : on ne peut pas s’opposer à des gens bienveillants et ouverts aux autres ! Mais derrière cette posture, il y a le brouillage de classes, et la fin de la classe moyenne. La classe moyenne telle qu’on l’a connue, celle des Trente Glorieuses, qui a profité de l’intégration économique, d’une ascension sociale conjuguée à une intégration politique et culturelle, n’existe plus même si, pour des raisons politiques, culturelles et anthropologiques, on continue de la faire vivre par le discours et les représentations. (…) C’est aussi une conséquence de la non-intégration économique. Aujourd’hui, quand on regarde les chiffres – notamment le dernier rapport sur les inégalités territoriales publié en juillet dernier –, on constate une hyper-concentration de l’emploi dans les grands centres urbains et une désertification de ce même emploi partout ailleurs. Et cette tendance ne cesse de s’accélérer ! Or, face à cette situation, ce même rapport préconise seulement de continuer vers encore plus de métropolisation et de mondialisation pour permettre un peu de redistribution. Aujourd’hui, et c’est une grande nouveauté, il y a une majorité qui, sans être « pauvre » ni faire les poubelles, n’est plus intégrée à la machine économique et ne vit plus là où se crée la richesse. Notre système économique nécessite essentiellement des cadres et n’a donc plus besoin de ces millions d’ouvriers, d’employés et de paysans. La mondialisation aboutit à une division internationale du travail : cadres, ingénieurs et bac+5 dans les pays du Nord, ouvriers, contremaîtres et employés là où le coût du travail est moindre. La mondialisation s’est donc faite sur le dos des anciennes classes moyennes, sans qu’on le leur dise ! Ces catégories sociales sont éjectées du marché du travail et éloignées des poumons économiques. Cependant, cette« France périphérique » représente quand même 60 % de la population. (…) Ce phénomène présent en France, en Europe et aux États-Unis a des répercussions politiques : les scores du FN se gonflent à mesure que la classe moyenne décroît car il est aujourd’hui le parti de ces « superflus invisibles » déclassés de l’ancienne classe moyenne. (…) Face à eux, et sans eux, dans les quinze plus grandes aires urbaines, le système marche parfaitement. Le marché de l’emploi y est désormais polarisé. Dans les grandes métropoles il faut d’une part beaucoup de cadres, de travailleurs très qualifiés, et de l’autre des immigrés pour les emplois subalternes dans le BTP, la restauration ou le ménage. Ainsi les immigrés permettent-ils à la nouvelle bourgeoisie de maintenir son niveau de vie en ayant une nounou et des restaurants pas trop chers. (…) Il n’y a aucun complot mais le fait, logique, que la classe supérieure soutient un système dont elle bénéficie – c’est ça, la « main invisible du marché» ! Et aujourd’hui, elle a un nom plus sympathique : la « société ouverte ». Mais je ne pense pas qu’aux bobos. Globalement, on trouve dans les métropoles tous ceux qui profitent de la mondialisation, qu’ils votent Mélenchon ou Juppé ! D’ailleurs, la gauche votera Juppé. C’est pour cela que je ne parle ni de gauche, ni de droite, ni d’élites, mais de « la France d’en haut », de tous ceux qui bénéficient peu ou prou du système et y sont intégrés, ainsi que des gens aux statuts protégés : les cadres de la fonction publique ou les retraités aisés. Tout ce monde fait un bloc d’environ 30 ou 35 %, qui vit là où la richesse se crée. Et c’est la raison pour laquelle le système tient si bien. (…) La France périphérique connaît une phase de sédentarisation. Aujourd’hui, la majorité des Français vivent dans le département où ils sont nés, dans les territoires de la France périphérique il s’agit de plus de 60 % de la population. C’est pourquoi quand une usine ferme – comme Alstom à Belfort –, une espèce de rage désespérée s’empare des habitants. Les gens deviennent dingues parce qu’ils savent que pour eux « il n’y a pas d’alternative » ! Le discours libéral répond : « Il n’y a qu’à bouger ! » Mais pour aller où ? Vous allez vendre votre baraque et déménager à Paris ou à Bordeaux quand vous êtes licencié par ArcelorMittal ou par les abattoirs Gad ? Avec quel argent ? Des logiques foncières, sociales, culturelles et économiques se superposent pour rendre cette mobilité quasi impossible. Et on le voit : autrefois, les vieux restaient ou revenaient au village pour leur retraite. Aujourd’hui, la pyramide des âges de la France périphérique se normalise. Jeunes, actifs, retraités, tous sont logés à la même enseigne. La mobilité pour tous est un mythe. Les jeunes qui bougent, vont dans les métropoles et à l’étranger sont en majorité issus des couches supérieures. Pour les autres ce sera la sédentarisation. Autrefois, les emplois publics permettaient de maintenir un semblant d’équilibre économique et proposaient quelques débouchés aux populations. Seulement, en plus de la mondialisation et donc de la désindustrialisation, ces territoires ont subi la retraite de l’État. (…) Aujourd’hui, ce parc privé « social de fait » s’est gentrifié et accueille des catégories supérieures. Quant au parc social, il est devenu la piste d’atterrissage des flux migratoires. Si l’on regarde la carte de l’immigration, la dynamique principale se situe dans le Grand Ouest, et ce n’est pas dans les villages que les immigrés s’installent, mais dans les quartiers de logements sociaux de Rennes, de Brest ou de Nantes. (…) In fine, il y a aussi un rejet du multiculturalisme. Les gens n’ont pas envie d’aller vivre dans les derniers territoires des grandes villes ouverts aux catégories populaires : les banlieues et les quartiers à logements sociaux qui accueillent et concentrent les flux migratoires. (…) En réalité, [mixité sociale » et « mixité ethnique »] vont rarement ensemble. En région parisienne, on peut avoir un peu de mixité sociale sans mixité ethnique. La famille maghrébine en phase d’ascension sociale achète un pavillon à proximité des cités. Par ailleurs, les logiques séparatistes se poursuivent et aujourd’hui les ouvriers, les cadres de la fonction publique et les membres de la petite bourgeoisie maghrébine en ascension sociale évitent les quartiers où se concentre l’immigration africaine. Ça me fait penser à la phrase de Valls sur l’apartheid. Il devait penser à Évry, où le quartier des Pyramides s’est complètement ethnicisé : là où vivaient hier des Blancs et des Maghrébins, ne restent plus aujourd’hui que des gens issus de l’immigration subsaharienne. En réalité, tout le monde – le petit Blanc, le bobo comme le Maghrébin en phase d’ascension sociale – souhaite éviter le collège pourri du coin et contourne la carte scolaire. On est tous pareils, seul le discours change… (…) À catégories égales, la mobilité sociale est plus forte dans les grandes métropoles. C’est normal : c’est là que se concentrent les emplois. Contrairement aux zones rurales, où l’accès au marché de l’emploi et à l’enseignement supérieur est difficile, les aires métropolitaines offrent des opportunités y compris aux catégories modestes. Or ces catégories, compte tenu de la recomposition démographique, sont aujourd’hui issues de l’immigration. Cela explique l’intégration économique et sociale d’une partie de cette population. Évidemment, l’ascension sociale reste minoritaire mais c’est une constante des milieux populaires depuis toujours : quand on naît « en bas » , on meurt « en bas » . (…) les classes populaires immigrées bénéficient simplement d’un atout : celui de vivre « là où ça se passe » . Il ne s’agit pas d’un privilège résultant d’une politique volontariste. Tout ça s’est fait lentement. Il y a des logiques démographiques, foncières et économiques. Il faut avoir à l’esprit que la France périphérique n’est pas 100 % blanche, elle comporte aussi des immigrés, et puis il y a également les DOM-TOM, territoires ultrapériphériques ! (..) Notre erreur est d’avoir pensé qu’on pouvait appliquer le modèle mondialisé économique sans obtenir ses effets sociétaux, c’est-à-dire le multiculturalisme et une forme de communautarisme. La prétention française, c’était de dire : « Nous, gros malins de Français, allons faire la mondialisation républicaine ! » Il faut constater que nous sommes devenus une société américaine comme les autres. La laïcité et l’assimilation sont mortes de facto. Il suffit d’écouter les élèves d’un collège pour s’en convaincre : ils parlent de Noirs, de Blancs, d’Arabes. La société multiculturelle mondialisée génère partout les mêmes tensions et paranoïas identitaires, nous sommes banalement dans ce schéma en France. Dans ce contexte, la question du rapport entre minorité et majorité est en permanence posée, quelle que soit l’origine. Quand ils deviennent minoritaires, les Maghrébins eux-mêmes quittent les cités qui concentrent l’immigration subsaharienne. Sauf que comme en France il n’y a officiellement ni religion ni race, on ne peut pas en parler… Ceux qui osent le faire, comme Michèle Tribalat, le paient cher. (…) La création de zones piétonnières fait augmenter les prix du foncier. Et les aménagements écolos des villes correspondent, de fait, à des embourgeoisements. Tous ces dispositifs amènent un renchérissement du foncier et davantage de gentrification. Pour baisser les prix ? Il faut moins de standing. Or la pression est forte : à Paris, plus de 40 % de la population active est composée de cadres. C’est énorme ! Même le XX e arrondissement est devenu une commune bourgeoise. Et puis l’embourgeoisement est un rouleau compresseur. On avait pensé que certaines zones resteraient populaires, comme la Seine-et-Marne, mais ce n’est pas le cas. Ce système reproduit le modèle du marché mondialisé, c’est-à-dire qu’il se sépare des gens dont on n’a pas besoin pour faire tourner l’économie. (…) La politique municipale de Bordeaux est la même que celle de Lyon ou de Paris. Il y a une logique qui est celle de la bourgeoisie mondialisée, qu’elle soit de droite ou de gauche. Elle est libérale-libertaire, tantôt plus libertaire (gauche), tantôt plus libérale (droite)… (…) L’un des codes fondamentaux de la nouvelle bourgeoisie est l’ouverture. Si on lâche ce principe, on est presque en phase de déclassement. Le vote populiste, c’est celui des gens qui ne sont plus dans le système, les « ratés » , et personne, dans le milieu bobo, n’a envie d’avoir l’image d’un loser. Le discours d’ouverture de la supériorité morale du bourgeois est presque un signe extérieur de richesse. C’est un attribut d’intégration. Aux yeux de la classe dominante, un homme tolérant est quelqu’un qui a fondamentalement compris le monde. (…) Mais plus personne ne l’écoute ! Quand on regarde catégorie après catégorie, c’est un processus de désaffiliation qui s’enchaîne et se reproduit, incluant notamment le divorce des banlieues avec la gauche. Le magistère de la France d’en haut est terminé ! Électoralement, on le voit déjà avec la montée de l’abstention et du vote FN. Le FN existe uniquement parce qu’il est capable de capter ce qui vient d’en bas, pas parce qu’il influence le bas. Ce sont les gens qui influencent le discours du FN, et pas le contraire ! Ce n’est pas le discours du FN qui imprègne l’atmosphère ! Le Pen père n’était pas ouvriériste, ce sont les ouvriers qui sont allés vers lui. Le FN s’est mis à parler du rural parce qu’il a observé des cartes électorales… les campagnes sont un désert politique rempli de Français dans l’attente d’une nouvelle offre. Bref, ce système ne peut pas perdurer. (…) Si l’on regarde le dernier sondage Ipsos réalisé dans 22 pays, on y découvre que seulement 11 % des Français (dont beaucoup d’immigrés !) considèrent que l’immigration est positive pour le pays. C’est marrant, les journalistes sont 90 % à penser le contraire. En vérité, il n’y a plus de débat sur l’immigration : tout le monde est d’accord sauf des gens qui nous mentent… (…) Les ministres et gouvernements successifs sont pris dans la même contradiction : ils ont choisi un modèle économique qui crée de la richesse, mais qui n’est pas socialement durable, qui ne fait pas société. Ils n’ont de fait aucune solution, si ce n’est de gérer le court terme en faisant de la redistribution. La dernière idée dans ce sens est le revenu universel, ce qui fait penser qu’on a définitivement renoncé à tout espoir d’un développement économique de la France périphérique. Christophe Guilluy

Experts et commentateurs se sont, dans leur grande majorité, mis le doigt dans l’œil parce qu’ils pensent à l’intérieur du système. À Paris comme à Washington, on reste persuadé qu’un «outsider» n’a aucune chance face aux appareils des partis, des lobbies et des machines électorales. Que ce soit dans notre monarchie républicaine ou dans leur hiérarchie de Grands Électeurs, si l’on n’est pas un familier du sérail, on n’existe pas. Tout le dédain et la condescendance envers Trump, qui n’était jusqu’ici connu que par ses gratte-ciel et son émission de téléréalité, pouvaient donc s’afficher envers cette grosse brute qui ne sait pas rester à sa place. On connaît la suite. (…) Trump est l’un des premiers à avoir compris et utilisé la désintermédiation. Ce n’est pas vraiment l’ubérisation de la politique, mais ça y ressemble quelque peu. Quand je l’ai interrogé sur le mouvement qu’il suscitait dans la population américaine, il m’a répondu: Twitter, Facebook et Instagram. Avec ses 15 millions d’abonnés, il dispose d’une force de frappe avec laquelle il dialogue sans aucun intermédiaire. Il y a trente ans, il écrivait qu’aucun politique ne pouvait se passer d’un quotidien comme le New York Times. Aujourd’hui, il affirme que les réseaux sociaux sont beaucoup plus efficaces – et beaucoup moins onéreux – que la possession de ce journal. (…) Là-bas comme ici, l’avenir n’est plus ce qu’il était, la classe moyenne se désosse, la précarité est toujours prégnante, les attentats terroristes ne sont plus, depuis un certain 11 septembre, des images lointaines vues sur petit ou grand écran. (…) Et la fureur s’explique par le décalage entre la ritournelle de «Nous sommes la plus grande puissance et le plus beau pays du monde» et le «Je n’arrive pas à finir le mois et payer les études de mes enfants et l’assurance médicale de mes parents». Sans parler de l’écart toujours plus abyssal entre riches et modestes. (…) Il existe, depuis quelques années, un étonnant rapprochement entre les problématiques européennes et américaines. Qui aurait pu penser, dans ce pays d’accueil traditionnel, que l’immigration provoquerait une telle hostilité chez certains, qui peut permettre à Trump de percer dans les sondages en proclamant sa volonté de construire un grand mur? Il y a certes des points communs avec Marine Le Pen, y compris dans la nécessité de relocaliser, de rebâtir des frontières et de proclamer la grandeur de son pays. Mais évidemment, Trump a d’autres moyens que la présidente du Front National… De plus, répétons-le, c’est d’abord un pragmatique et un négociateur. Je ne crois pas que ce soit les qualités les plus apparentes de Marine Le Pen… (…) Son programme économique le situe beaucoup plus à gauche que les caciques Républicains et les néo-conservateurs proches d’Hillary Clinton qui le haïssent, parce que lui croit, dans certains domaines, à l’intervention de l’État et aux limites nécessaires du laisser-faire, laisser-aller. (…) Il ne ménage personne et peut aller beaucoup plus loin que Marine Le Pen, tout simplement parce qu’il n’a jamais eu à régler le problème du père fondateur et encore moins à porter le fardeau d’une étiquette tout de même controversée. Sa marque à lui, ce n’est pas la politique, mais le bâtiment et la réussite. Ça change pas mal de choses. (…) il trouve insupportable que des villes comme Paris et Bruxelles, qu’il adore et a visitées maintes fois, deviennent des camps retranchés où l’on n’est même pas capable de répliquer à un massacre comme celui du Bataclan. On peut être vent debout contre le port d’arme, mais, dit-il, s’il y avait eu des vigiles armés boulevard Voltaire, il n’y aurait pas eu autant de victimes. Pour lui, un pays qui ne sait pas se défendre est un pays en danger de mort. (…) Il s’entendra assez bien avec Poutine pour le partage des zones d’influence, et même pour une collaboration active contre Daesh et autres menaces, mais, comme il le répète sur tous les tons, l’Amérique de Trump ne défendra que les pays qui paieront pour leur protection. Ça fait un peu Al Capone, mais ça a le mérite de la clarté. Si l’Europe n’a pas les moyens de protéger son identité, son mode de vie, ses valeurs et sa culture, alors, personne ne le fera à sa place. En résumé, pour Trump, la politique est une chose trop grave pour la laisser aux politiciens professionnels, et la liberté un état trop fragile pour la confier aux pacifistes de tout poil. André Bercoff

La grande difficulté, avec Donald Trump, c’est qu’on est à la fois face à une caricature et face à un phénomène bien plus complexe. Une caricature d’abord, car tout chez lui, semble magnifié. L’appétit de pouvoir, l’ego, la grossièreté des manières, les obsessions, les tweets épidermiques, l’étalage voyant de son succès sur toutes les tours qu’il a construites et qui portent son nom. Donald Trump joue en réalité à merveille de son côté caricatural, il simplifie les choses, provoque, indigne, et cela marche parce que notre monde du 21e siècle se gargarise de ces simplifications outrancières, à l’heure de l’information immédiate et fragmentée. La machine médiatique est comme un ventre qui a toujours besoin de nouveaux scandales et Donald, le commercial, le sait mieux que personne, parce qu’il a créé et animé une émission de téléréalité pendant des années. Il sait que la politique américaine actuelle est un grand cirque, où celui qui crie le plus fort a souvent raison parce que c’est lui qui «fait le buzz». En même temps, ne voir que la caricature qu’il projette serait rater le phénomène Trump et l’histoire stupéfiante de son succès électoral. Derrière l’image télévisuelle simplificatrice, se cache un homme intelligent, rusé et avisé, qui a géré un empire de milliards de dollars et employé des dizaines de milliers de personnes. Ce n’est pas rien! Selon plusieurs proches du milliardaire que j’ai interrogés, Trump réfléchit de plus à une candidature présidentielle depuis des années, et il a su capter, au-delà de l’air du temps, la colère profonde qui traversait l’Amérique, puis l’exprimer et la chevaucher. Grâce à ses instincts politiques exceptionnels, il a vu ce que personne d’autre – à part peut-être le démocrate Bernie Sanders – n’avait su voir: le gigantesque ras le bol d’un pays en quête de protection contre les effets déstabilisants de la globalisation, de l’immigration massive et du terrorisme islamique; sa peur du déclin aussi. En ce sens, Donald Trump s’est dressé contre le modèle dominant plébiscité par les élites et a changé la nature du débat de la présidentielle. Il a remis à l’ordre du jour l’idée de protection du pays, en prétendant au rôle de shérif aux larges épaules face aux dangers d’un monde instable et dangereux. Cela révèle au minimum une personnalité sacrément indépendante, un côté indomptable qui explique sans doute l’admiration de ses partisans…Ils ont l’impression que cet homme explosif ne se laissera impressionner par rien ni personne. Beaucoup des gens qui le connaissent affirment d’ailleurs que Donald Trump a plusieurs visages: le personnage public, flashy, égotiste, excessif, qui ne veut jamais avouer ses faiblesses parce qu’il doit «vendre» sa marchandise, perpétuer le mythe, et un personnage privé plus nuancé, plus modéré et plus pragmatique, qui sait écouter les autres et ne choisit pas toujours l’option la plus extrême…Toute la difficulté et tout le mystère, pour l’observateur est de s’y retrouver entre ces différents Trump. C’est loin d’être facile, surtout dans le contexte de quasi hystérie qui règne dans l’élite médiatique et politique américaine, tout entière liguée contre lui. Il est parfois très difficile de discerner ce qui relève de l’analyse pertinente ou de la posture de combat anti-Trump. (…) à de rares exceptions près, les commentateurs n’ont pas vu venir le phénomène Trump, parce qu’il était «en dehors des clous», impensable selon leurs propres «grilles de lecture». Trop scandaleux et trop extrême, pensaient-ils. Il a fait exploser tant de codes en attaquant ses adversaires au dessous de la ceinture et s’emparant de sujets largement tabous, qu’ils ont cru que «le grossier personnage» ne durerait pas! Ils se sont dit que quelqu’un qui se contredisait autant ou disait autant de contre vérités, finirait par en subir les conséquences. Bref, ils ont vu en lui soit un clown soit un fasciste – sans réaliser que toutes les inexactitudes ou dérapages de Trump lui seraient pardonnés comme autant de péchés véniels, parce qu’il ose dire haut et fort ce que son électorat considère comme une vérité fondamentale: à savoir que l’Amérique doit faire respecter ses frontières parce qu’un pays sans frontières n’est plus un pays. Plus profondément, je pense que les élites des deux côtes ont raté le phénomène Trump (et le phénomène Sanders), parce qu’elles sont de plus en plus coupées du peuple et de ses préoccupations, qu’elles vivent entre elles, se cooptent entre elles, s’enrichissent entre elles, et défendent une version «du progrès» très post-moderne, détachée des préoccupations de nombreux Américains. Soyons clairs, si Trump est à bien des égards exaspérant et inquiétant, il y a néanmoins quelque chose de pourri et d’endogame dans le royaume de Washington. Le peuple se sent hors jeu. (…) Ce statut de milliardaire du peuple est crédible parce qu’il ne s’est jamais senti membre de l’élite bien née, dont il aime se moquer en la taxant «d’élite du sperme chanceux». Cette dernière ne l’a d’ailleurs jamais vraiment accepté, lui le parvenu de Queens, venu de la banlieue, qui aime tout ce qui brille. Il ne faut pas oublier en revanche que Donald a grandi sur les chantiers de construction, où il accompagnait son père déjà tout petit, ce qui l’a mis au contact des classes populaires. Il parle exactement comme eux! Quand je me promenais à travers l’Amérique à la rencontre de ses électeurs, c’est toujours ce dont ils s’étonnaient. Ils disaient: «Donald parle comme nous, pense comme nous, est comme nous». Le fait qu’il soit riche, n’est pas un obstacle parce qu’on est en Amérique, pas en France. Les Américains aiment la richesse et le succès. (…) L’un des atouts de Trump, pour ses partisans, c’est qu’il est politiquement incorrect dans un pays qui l’est devenu à l’excès. Sur l’islam radical (qu’Obama ne voulait même pas nommer comme une menace!), sur les maux de l’immigration illégale et maints autres sujets. Ses fans se disent notamment exaspérés par le tour pris par certains débats, comme celui sur les toilettes «neutres» que l’administration actuelle veut établir au nom du droit des «personnes au genre fluide» à «ne pas être offensés». Ils apprécient que Donald veuille rétablir l’expression de Joyeux Noël, de plus en plus bannie au profit de l’expression Joyeuses fêtes, au motif qu’il ne faut pas risquer de blesser certaines minorités religieuses non chrétiennes…Ils se demandent pourquoi les salles de classe des universités, lieu où la liberté d’expression est supposée sacro-sainte, sont désormais surveillées par une «police de la pensée» étudiante orwellienne, prête à demander des comptes aux professeurs chaque fois qu’un élève s’estime «offensé» dans son identité…Les fans de Trump sont exaspérés d’avoir vu le nom du club de football américain «Red Skins» soudainement banni du vocabulaire de plusieurs journaux, dont le Washington Post, (et remplacé par le mot R…avec trois points de suspension), au motif que certaines tribus indiennes jugeaient l’appellation raciste et insultante. (Le débat, qui avait mobilisé le Congrès, et l’administration Obama, a finalement été enterré après de longs mois, quand une enquête a révélé que l’écrasante majorité des tribus indiennes aimait finalement ce nom…). Dans ce contexte, Trump a été jugé«rafraîchissant» par ses soutiens, presque libérateur. (…) Pour moi, le phénomène Trump est la rencontre d’un homme hors normes et d’un mouvement de rébellion populaire profond, qui dépasse de loin sa propre personne. C’est une lame de fond, anti globalisation et anti immigration illégale, qui traverse en réalité tout l’Occident. Trump surfe sur la même vague que les politiques britanniques qui ont soutenu le Brexit, ou que Marine Le Pen en France. La différence, c’est que Trump est une version américaine du phénomène, avec tout ce que cela implique de pragmatisme et d’attachement au capitalisme. (…) Trump n’est pas un idéologue. Il a longtemps été démocrate avant d’être républicain et il transgresse les frontières politiques classiques des partis. Favorable à une forme de protectionnisme et une remise en cause des accords de commerce qui sont défavorables à son pays, il est à gauche sur les questions de libre échange, mais aussi sur la protection sociale des plus pauvres, qu’il veut renforcer, et sur les questions de société, sur lesquelles il affiche une vision libérale de New Yorkais, certainement pas un credo conservateur clair. De ce point de vue là, il est post reaganien. Mais Donald Trump est clairement à droite sur la question de l’immigration illégale et des frontières, et celle des impôts. Au fond, c’est à la fois un marchand et un nationaliste, qui se voit comme un pragmatique, dont le but sera de faire «des bons deals» pour son pays. Il n’est pas là pour changer le monde, contrairement à Obama. Ce qu’il veut, c’est remettre l’Amérique au premier plan, la protéger. Son instinct de politique étrangère est clairement du côté des réalistes et des prudents, car Trump juge que les Etats-Unis se sont laissé entrainer dans des aventures qui les ont affaiblis et n’ont pas réglé les crises. Il ne veut plus d’une Amérique jouant les gendarmes du monde. Mais vu sa tendance aux volte face et vu ce qu’il dit sur le rôle que devrait jouer l’Amérique pour venir à bout de la menace de l’islam radical, comme elle l’a fait avec le nazisme et le communisme, Donald Trump pourrait fort bien changer d’avis, et revenir à un credo plus interventionniste avec le temps. Ses instincts sont au repli, mais il reste largement imprévisible. (…) De nombreuses questions se posent sur son caractère, ses foucades, son narcissisme et sa capacité à se contrôler, si importante chez le président de la première puissance du monde! Je ne suis pas pour autant convaincue par l’image de «Hitler», fasciste et raciste, qui lui a été accolée par la presse américaine. Hitler avait écrit Mein Kamp. Donald Trump, lui, a écrit «L ‘art du deal» et avait envisagé juste après la publication de ce premier livre, de se présenter à la présidence en prenant sur son ticket la vedette de télévision afro-américaine démocrate Oprah Winfrey, un élément qui ne colle pas avec l’image d’un raciste anti femmes! Ses enfants et nombre de ses collaborateurs affirment qu’il ne discrimine pas les gens en fonction de leur sexe ou de la couleur de leur peau, mais en fonction de leurs mérites, et que c’est pour cette même raison qu’il est capable de s’en prendre aux représentants du sexe faible ou des minorités avec une grande brutalité verbale, ne voyant pas la nécessité de prendre des gants. Les questions les plus lourdes concernant Trump, sont selon moi plutôt liées à la manière dont il réagirait, s’il ne parvenait pas à tenir ses promesses, une fois à la Maison-Blanche. Tout président américain est confronté à la complexité de l’exercice du pouvoir dans un système démocratique extrêmement contraignant. Cet homme d’affaires habitué à diriger un empire immobilier pyramidal, dont il est le seul maître à bord, tenterait-il de contourner le système pour arriver à ses fins et prouver au peuple qu’il est bien le meilleur, en agissant dans une zone grise, avec l’aide des personnages sulfureux qui l’ont accompagné dans ses affaires? Et comment se comporterait-il avec ses adversaires politiques ou les représentants de la presse, vu la brutalité et l’acharnement dont il fait preuve envers ceux qui se mettent sur sa route? Hériterait-on d’un Berlusconi ou d’un Nixon puissance 1000? Autre interrogation, vu la fascination qu’exerce sur lui le régime autoritaire de Vladimir Poutine: serait-il prêt à sacrifier le droit international et l’indépendance de certains alliés européens, pour trouver un accord avec le patron du Kremlin sur les sujets lui tenant à cœur, notamment en Syrie? Bref, pourrait-il accepter une forme de Yalta bis, et remettre en cause le rôle de l’Amérique dans la défense de l’ordre libéral et démocratique de l’Occident et du monde depuis 1945? Autant de questions cruciales auxquelles Donald Trump a pour l’instant répondu avec plus de désinvolture que de clarté. Laure Mandeville

Après les référendums de 2005 (France et Pays-Bas) et le Brexit (2016), voici une nouvelle surprise avec l’élection de Donald Trump par une franche majorité d’Américains. À chaque fois, le suffrage universel a eu raison des médias, des sondeurs et de leurs commanditaires. On peut au moins se réjouir de cette vitalité démocratique. (…) C’est en partie en raison du libre-échange et du primat de la finance que les électeurs américains ont voté pour Donald Trump : il a su capter leur colère sourde, tout comme d’ailleurs le candidat démocrate Bernie Sanders, rival malheureux d’Hillary Clinton. L’autre motif qui a conduit à la victoire de Trump et à l’élimination de Sanders tient à l’exaspération d’une majorité de citoyens face aux tromperies de l’utopie « multiculturaliste » et de la société « ouverte ». À preuve le vote de l’Iowa en faveur de Donald Trump : dans cet État plutôt prospère, avec un faible taux de chômage, c’est évidemment l’enjeu multiculturaliste qui a fait basculer les électeurs. En effet, l’élection en 2008 d’un président noir (pas un Afro-Américain mais un métis, fils d’une blanche du Kansas et d’un Kényan) n’a pas empêché le retour à de nouvelles formes de ségrégation raciale. C’est ainsi que la candidate démocrate Hillary Clinton a tenté de jouer la carte « racialiste » en cajolant les électeurs afro-américains et latinos. Mais sans doute s’est-elle trompée dans son évaluation du vote latino : beaucoup d’Étasuniens latino-américains aspirent à leur intégration dans la classe moyenne et ne se sentent guère solidaires des Afro-Américains. Le même phénomène s’observe en Europe de l’Ouest, sous l’effet d’un emballement migratoire sans précédent dans l’Histoire. Les nouveaux arrivants font bloc avec leur « communauté » dans les quartiers et les écoles : Africains de la zone équatoriale, Sahéliens, Maghrébins, Turcs, Orientaux, Chinois etc. Il compromettent ce faisant l’intégration des immigrants plus anciennement installés. À quoi les classes dirigeantes répondent par des propos hors-contexte sur le « vivre-ensemble » et l’occultation de la mémoire. La chancelière Angela Merkel et même le pape François ont perçu les dangers de cette politique dans leurs dernières déclarations, en novembre 2016. Quant aux élus français, qui ont abandonné leur souveraineté à Bruxelles et Berlin et se tiennent désormais à la remorque des puissants, ils feraient bien de prendre à leur tour la mesure de l’exaspération populaire face au néolibéralisme financier, au multiculturalisme et à l’emballement migratoire. Ils se doivent de nommer et analyser ces phénomènes sans faux-semblants, et de préconiser des solutions respectueuses de la démocratie. Hérodote

Make no mistake about it: this election is Barack Obama’s legacy. He pushed hard for Hillary Clinton in the end because he understood that as such. And it was all for naught. No celebrity, no sports star, and no current president with a strong approval rating was enough to drag Hillary Clinton over the finish line. (…) Last night Jamelle Bouie and Van Jones voiced something I expect we will hear from many of Obama’s firmest supporters in the coming weeks – the idea that Trump represents a “whitelash” against eight years of Obama. But this dramatically oversimplifies the case, particularly if as it seems at the moment Trump won more minority votes than Mitt Romney in 2012. In fact, as Nate Cohn notes, Clinton failed in areas of the country where Obama’s support had been strongest among white Americans. She failed to keep pace with Obama in the Rust Belt states that he won repeatedly. Her vaunted GOTV machine failed to attract the votes of young people, of union members, and of minorities to the degree necessary to win. And meanwhile, Trump’s utter lack of a campaign was more than made up for by the emotional dedication of his supporters. This was about more than just race – it was a sustained rejection of the country’s ruling class. But expect the media to try to make it about two things: race, and about Hillary Clinton’s lousy campaign. (…) The majority of political reporters never seemed to get outside their bubble. They spoke to anti-Trump conservatives, and printed anti-Trump views from conservatives, but rarely would even publish the sorts of views I and others have been sounding for months about the real and rational gripes of Trump voters. Many in the media preferred the caricature to the real thing. If you are a member of the media who does not know anyone who was pro-Trump, who has no Trump voters among your family or friends, realize how thick your bubble is. Change this. Don’t stick to the old sources, who clearly didn’t know what was going on – add new ones, who offer the perspective from the ground. (…) What is clear is this: Donald Trump is the man Americans have chosen as their vehicle for the dramatic change they demand from Washington. They have utterly rejected the change offered in the eight year Barack Obama agenda as wholly insufficient. And they have given Trump the rare gift of a united government in order to make those changes happen. They have tossed aside the assumptions of an elite class of gatekeepers and commentators whose opinions they disrespect and disavow. And they have sent a message to Washington that nothing less than wholesale change will satisfy them, including a change in the fundamental character of the commander in chief. Ben Domenech

Since the 1960s, when America finally became fully accountable for its past, deference toward all groups with any claim to past or present victimization became mandatory. The Great Society and the War on Poverty were some of the first truly deferential policies. Since then deference has become an almost universal marker of simple human decency that asserts one’s innocence of the American past. (…) Since the ’60s the Democratic Party, and liberalism generally, have thrived on the power of deference. When Hillary Clinton speaks of a “basket of deplorables,“ she follows with a basket of isms and phobias—racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia and Islamaphobia. Each ism and phobia is an opportunity for her to show deference toward a victimized group and to cast herself as America’s redeemer. And, by implication, conservatism is bereft of deference. (…) And they have been fairly successful in this so that many conservatives are at least a little embarrassed to “come out” as it were. Conservatism is an insurgent point of view, while liberalism is mainstream. And this is oppressive for conservatives because it puts them in the position of being a bit embarrassed by who they really are and what they really believe. Deference has been codified in American life as political correctness. And political correctness functions like a despotic regime. It is an oppressiveness that spreads its edicts further and further into the crevices of everyday life. We resent it, yet for the most part we at least tolerate its demands. (…) And into all this steps Mr. Trump, a fundamentally limited man but a man with overwhelming charisma, a man impossible to ignore. The moment he entered the presidential contest America’s long simmering culture war rose to full boil. Mr. Trump was a non-deferential candidate. He seemed at odds with every code of decency. He invoked every possible stigma, and screechingly argued against them all. He did much of the dirty work that millions of Americans wanted to do but lacked the platform to do. Thus Mr. Trump’s extraordinary charisma has been far more about what he represents than what he might actually do as the president. He stands to alter the culture of deference itself. After all, the problem with deference is that it is never more than superficial. We are polite. We don’t offend. But we don’t ever transform people either. Out of deference we refuse to ask those we seek to help to be primarily responsible for their own advancement. Yet only this level of responsibility transforms people, no matter past or even present injustice. Some 3,000 shootings in Chicago this year alone is the result of deference camouflaging a lapse of personal responsibility with empty claims of systemic racism. As a society we are so captive to our historical shame that we thoughtlessly rush to deference simply to relieve the pressure. And yet every deferential gesture—the war on poverty, affirmative action, ObamaCare, every kind of “diversity” scheme—only weakens those who still suffer the legacy of our shameful history. Deference is now the great enemy of those toward whom it gushes compassion. Societies, like individuals, have intuitions. Donald Trump is an intuition. At least on the level of symbol, maybe he would push back against the hegemony of deference—if not as a liberator then possibly as a reformer. Possibly he could lift the word responsibility out of its somnambulant stigmatization as a judgmental and bigoted request to make of people. This, added to a fundamental respect for the capacity of people to lift themselves up, could go a long way toward a fairer and better America. Shelby Steele

For the past six months, one big question has loomed over the 2016 election: Is the candidacy of Donald J. Trump an amusing bit of reality TV or a terrifying and dangerous challenge to the country’s political system? At first, Trump’s popularity was easy to dismiss. It was nothing more than a phase, the result of Trump’s celebrity status and his talent for provocation. His antics made it hard to look away, but it was easy to convince yourself that Trump mania would never lead to anything serious, like the Republican nomination. It was especially easy to come to that conclusion if you were reading FiveThirtyEight, the statistics-driven news website founded by Nate Silver. Since the beginning of Trump’s campaign last June, the election guru and his colleagues have been consistently bearish on Trump’s chances. Silver, who made his name by using cold hard math to call 49 out of 50 states in the 2008 general election and all 50 in 2012, has served as a reassuring voice in the midst of Trump’s shocking rise. For those of us who didn’t want to believe we lived in a country where Donald Trump could be president, Silver’s steady, level-headed certainty felt just as soothing as his unwavering confidence in Barack Obama’s triumph over Mitt Romney four years ago. What exactly has Silver been saying? In September, he told CNN’s Anderson Cooper that Trump had a roughly 5-percent chance of beating his GOP rivals. In November, he explained that Trump’s national following was about as negligible as the share of Americans who believe the Apollo moon landing was faked. On Twitter, he compared Trump to the band Nickelback, which he described as being “[d]isliked by most, super popular with a few.” In a post titled “Why Donald Trump Isn’t A Real Candidate, In One Chart,” Silver’s colleague Harry Enten wrote that Trump had a better chance of “playing in the NBA Finals” than winning the Republican nomination. Multiple times over the past six months, Silver has reminded his readers that four years ago, daffy fly-by-nighters like Herman Cain and Michele Bachmann led the GOP field at various points. Trump’s poll numbers, he wrote, would drop just like theirs had. In one August post, “Donald Trump’s Six Stages of Doom,” Silver actually laid out a schedule for the candidate’s inevitable collapse. (…) It’s clear, now, that Silver and his fellow analysts at FiveThirtyEight underestimated Trump. Silver himself recently admitted as much, writing in a blog post published last week that he’d been too skeptical about Trump’s chances. (…) Maybe, like many people who have watched Trump’s rise with increasing horror, Silver latched onto a narrative that justified rejecting the Apprentice star’s achievements, identifying them as symptoms of a media bubble rather than a reflection of real popular sentiment. If that’s the case, Silver turns out to have a good bit in common with the pundits that he and his unemotional, numbers-driven worldview were supposed to render obsolete. Faced with uncertainty, Silver chose to go all in on an outcome that felt right, one that meshed with his preexisting beliefs about how the world is supposed to work. (…)Missing the significance of Trumpism is a different kind of failure than, say, calling the 2012 election for Mitt Romney. It also might be a more damning one. Botching your general election forecast by a couple of percentage points suggests a flawed mathematical formula. Actively denying the reality of Trump’s success suggests Silver may never have been capable of explaining the world in a way so many believed he could in 2008 and 2012, when he was telling them how likely it was that Obama would become, and remain, the president. Leon Neyfakh (Jan. 2016)

Mr Silver predicted, with an absurdly precise 71.4% chance, that Mrs Clinton would take 302 electoral votes and beat Mr Trump by 3.6% in the popular vote. He was wildly incorrect. (As of the writing of this article, Mr Trump will win 306 electoral votes but will lose the popular vote by merely 0.2%.) Even worse, Mr Silver got several key states wrong: He predicted that Clinton would win Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Florida. In reality, Trump swept all of them. Alex Berezow

It was a big polling miss in the worst possible race. On the eve of America’s presidential election, national surveys gave Hillary Clinton a lead of around four percentage points, which betting markets and statistical models translated into a probability of victory ranging from 70% to 99%. That wound up misfiring modestly: according to the forecast from New York Times’s Upshot, Mrs Clinton is still likely to win the popular vote, by more than a full percentage point. But at the state level, the errors were extreme. The polling average in Wisconsin gave her a lead of more than five points; she is expected to lose it by two and a half. It gave Mr Trump a relatively narrow two-point edge in Ohio; he ran away with the state by more than eight. He trailed in Michigan and Pennsylvania by four, and looks likely to take both by about a point. How did it all go wrong? Every survey result is made up of a combination of two variables: the demographic composition of the electorate, and how each group is expected to vote. Because some groups—say, young Hispanic men—are far less likely to respond than others (old white women, for example), pollsters typically weight the answers they receive to match their projections of what the electorate will look like. Polling errors can stem either from getting an unrepresentative sample of respondents within each group, or from incorrectly predicting how many of each type of voter will show up. The electoral map leaves no doubt as to how Mr Trump won. In states where white voters tend to be well-educated, such as Colorado and Virginia, the polls pegged the final results perfectly. Conversely, in northern states that have lots of whites without a college degree, Mr Trump blew his polls away—including ones he is still expected to lose, but by a far smaller margin than expected, such as Minnesota. The simplest explanation for this would be that these voters preferred him by an even larger margin than pollsters foresaw—the so-called “shy Trump” phenomenon, in which people might be wary of admitting they supported him. Pre-election polls gave little evidence for this phenomenon: they showed him with a massive 30-point lead among this group. But remarkably, even that figure wound up understating Mr Trump’s appeal to them: the national exit poll put him 39 points ahead. Given that such voters make up 58% of the eligible population in Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania—though a smaller share of those who actually turn out—this nine-point miss among them accounts for a large chunk of the overall error. It is also likely that less-educated whites, who historically have had a low propensity to vote, turned out in greater numbers than pollsters predicted. The Economist

Election polling is harder than other forms of survey research, because you must assess two things at once. Not only do you have to find out who people say they will support, you also have to estimate their likelihood of actually turning up to vote. So Trump may have been right in claiming that he’d created a new movement of people who had previously shunned political engagement. If so, pollsters who relied on prior voting behavior to predict who would turn out this time would have systematically underestimated Trump’s support. Problems with likely voter modeling could also mean that the pollsters overestimated the extent to which the “Obama coalition” of black, Latino, and younger voters would turn out for Clinton.(…) “Shy Trumpers,” who were embarrassed to admit their support for the GOP candidate, quietly delivered their verdict in the polling booths. This theory first emerged in the run-up to the Republican primaries, as pollsters noticed that Trump was doing better in online polls than in those conducted over the phone. The idea was that some of Trump’s supporters were embarrassed to admit their choice to a real person. The idea gained traction when a polling experiment run last December by Morning Consult seemed to confirm that the effect was real. In the match-up against Clinton, however, Trump’s advantage in online polls mostly evaporated. And when Morning Consult ran a poll with Politico in late October to specifically probe for the effect, it seemed to operate only among college-educated voters. “Overall, it didn’t look like it massively shifted the race,” Morning Consult’s Cartwright said. (…) Trump’s anti-establishment supporters believed the polls were rigged, and so they refused to answer the phone or respond to online surveys. For pollsters, this is a much darker possibility. The idea that the polls were rigged became a popular refrain among Trump’s supporters. So maybe these people simply refused to participate in polls, either on the phone or online. If so, all of the pollsters may have been systematically blind to many of the disaffected, mostly white voters who drove Trump to victory, especially in the Rust Belt states of the Midwest. “People who don’t like the government often perceive the polls as being part of the government,” said Johnson of the University of Illinois, who believes this is the most plausible explanation for the pollsters’ miss. BuzzFeed

L’effet Bradley (en anglais Bradley effect) (…) est le nom donné aux États-Unis au décalage souvent observé entre les sondages électoraux et les résultats des élections américaines quand un candidat blanc est opposé à un candidat non blanc (noir, hispanique, latino, asiatique ou océanien). Le nom du phénomène vient de Tom Bradley, un Afro-Américain qui perdit l’élection de 1982 au poste de gouverneur de Californie, à la surprise générale, alors qu’il était largement en tête dans tous les sondages. L’effet Bradley reflète une tendance de la part des votants, noirs aussi bien que blancs, à dire aux sondeurs qu’ils sont indécis ou qu’ils vont probablement voter pour le candidat noir ou issu de la minorité ethnique mais qui, le jour de l’élection, votent pour son opposant blanc. Une des théories pour expliquer l’effet Bradley est que certains électeurs donnent une réponse fausse lors des sondages, de peur qu’en déclarant leur réelle préférence, ils ne prêtent le flanc à la critique d’une motivation raciale de leur vote. Cet effet est similaire à celui d’une personne refusant de discuter de son choix électoral. Si la personne déclare qu’elle est indécise, elle peut ainsi éviter d’être forcée à entrer dans une discussion politique avec une personne partisane. La réticence à donner une réponse exacte s’étend parfois jusqu’aux sondages dits de sortie de bureau de vote. La façon dont les sondeurs conduisent l’interview peut être un déterminant dans la réponse du sondé. Wikipedia

Silicon Valley these days is a very intolerant place for people who do not hold so called ‘socially liberal’ ideas. In Silicon Valley, because of the high prevalence of highly smart people, there is a general stereotype that voting Republican is for dummies. So many people see considering supporting Republican candidates, particularly Donald Trump, anathema to the whole Silicon Valley ethos that values smarts and merit. A couple of friends thought that me supporting Trump made me unworthy of being part of the Silicon Valley tribe and stopped talking to me. At the end of the day, we choose our politics the way we choose our lovers and our friends — not so much out a rational analysis, but based on impressions and our own personal backgrounds. My main reason for supporting Trump is that I basically agree with the notion that unless the trend is stopped, our country is going to hell … The Silicon Valley elite is highly hypocritical on this matter. One of the reasons, I assume, they don’t like Trump is because on this area, as in many others, he is calling a spade a spade. I believe Trump is right in this case. … supporting Trump only offers [an] upside. Electing Hillary Clinton would keep the status quo. If Trump wins, there’s a whole set of new possibilities that would emerge for the nation. Even if it remains socially liberal, it would be good for it if the president were to be a Republican so that the Valley could recover a little bit of its rebel spirit (that was the case during the Bush years for instance). I believe that the increased relevance in national politics of companies like Google (whose Chairman [Eric] Schmidt has been very cozy with the Obama administration) and Apple (at the center of several political disputes) has been bad for the Valley. A Trump presidency would allow the Valley to focus on what it does best: dreaming and building the technology of the future, leaving politics for DC types. Silicon valley software engineer

Many people are saying to maybe their friends while they’re having a sip of Chardonnay in Washington or Boston, ‘Oh, I would never vote for him, he’s so – not politically correct,’ or whatever, but then they’re going to go and vote for him. Because he’s saying things that they would like to say, but they’re not politically courageous enough to say it and I think that’s the real question in this election. Trump is kind of a combination of the gun referendum, because he’s an emotional energy source for people who want to make sure that they’re voicing their concerns about all these issues – immigration, et cetera – but then I think there’s this other piece. They don’t find it to be correct or acceptable to a lot of their friends, but when push comes to shove, they’re going to vote for him. Gregory Payne (Emerson College)

Donald Trump performs consistently better in online polling where a human being is not talking to another human being about what he or she may do in the election. It’s because it’s become socially desirable, if you’re a college educated person in the United States of America, to say that you’re against Donald Trump. Kellyanne Conway (Trump campaign manager)

They’ll go ahead and vote for that candidate in the privacy of a [voting] booth But they won’t admit to voting for that candidate to somebody who’s calling them for a poll. Joe Bafumi (Dartmouth College)

Trump’s advantage in online polls compared with live telephone polling is eight or nine percentage points among likely voters. Kyle A. Dropp

It’s easier to express potentially ‘unacceptable’ responses on a screen than it is to give them to a person. Kathy Frankovic

This may be due to social desirability bias — people are more willing to express support for this privately than when asked by someone else. Douglas Rivers

In a May 2015 report, Pew Research analyzed the differences between results derived from telephone polling and those from online Internet polling. Pew determined that the biggest differences in answers elicited via these two survey modes were on questions in which social desirability bias — that is, “the desire of respondents to avoid embarrassment and project a favorable image to others” — played a role. In a detailed analysis of phone versus online polling in Republican primaries, Kyle A. Dropp, the executive director of polling and data science at Morning Consult, writes: Trump’s advantage in online polls compared with live telephone polling is eight or nine percentage points among likely voters. This difference, Dropp notes, is driven largely by more educated voters — those who would be most concerned with “social desirability.” These findings suggest that Trump will head into the general election with support from voters who are reluctant to admit their preferences to a live person in a phone survey, but who may well be inclined to cast a ballot for Trump on Election Day. The NYT (May 2016)

Les analystes politiques, les sondeurs et les journalistes ont donné à penser que la victoire d’Hillary Clinton était assurée avant l’élection. En cela, c’est une surprise, car la sphère médiatique n’imaginait pas la victoire du candidat républicain. Elle a eu tort. Si elle avait su observer la société américaine et entendre son malaise, elle n’aurait jamais exclu la possibilité d’une élection de Trump. Pour cette raison, ce n’est pas une surprise. (…) Sans doute, ils ont rejeté Donald Trump car ils le trouvaient – et c’est le cas – démagogue, populiste et vulgaire. Je n’ai d’ailleurs jamais vu une élection américaine avec un tel parti pris médiatique. Même le très réputé hebdomadaire britannique « The Economist » a fait un clin d’oeil à Hillary Clinton. Je pense que la stigmatisation sans précédent de Donald Trump par les médias a favorisé chez les électeurs américains la dissimulation de leur intention de vote auprès des instituts de sondage. En clair, un certain nombre de votants n’a pas osé admettre qu’il soutenait le candidat américain. Ce phénomène est classique en politique. Souvenez du 21 avril 2002 et de la qualification surprise de Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader du Front national, au second tour de l’élection présidentielle française. (…) A travers l’élection de Trump, certains Américains ont exprimé leur colère. Une partie de l’Amérique ne trouve pas ses gains dans la globalisation. Cette Amérique-là ne parvient pas à retrouver son niveau de vie d’avant la crise des subprimes, elle a le sentiment d’être abandonnée. Ce sentiment était particulièrement perceptible chez les ouvriers, qui voient l’industrie s’effilocher. Ne se sentant pas assez considérés, ils ont davantage choisi Donald Trump qu’Hillary Clinton. (…) Cette formule [victoire du peuple américain contre l’establishment] est très exagérée. Oui, une partie des électeurs de Donald Trump ont voté contre Washington et ses élites. Oui, certains Américains souffrent d’un mépris de classe, en particulier dans l’Amérique profonde. Mais dire que le peuple s’est tourné vers Trump est inexact. Le candidat républicain et la candidate démocrate sont au coude à coude en termes de suffrages exprimés [à 15 heures, 47,5% pour Trump et 47,6% pour Clinton , NDLR]. Au passage, nous avons affaire à deux candidats richissimes. Si ma mémoire est bonne, Donald Trump, pseudo-candidat du peuple, n’est pas issu de la classe ouvrière… (…) L’arrivée au pouvoir de dirigeants populistes s’explique avant tout par des spécificités locales. Après, il y a des effets communs. De nouvelles puissances émergent. Les gens se sentent décentrés. Il y a une surabondance d’innovations technologiques et scientifiques. Une partie de la société se sent déclassée. L’immigration accélère les mécanismes de recomposition culturelle. Aux Etats-Unis, les Blancs anglo-saxons deviennent minoritaires. Ceci induit une réaction exprimée en votant pour un candidat populiste : Donald Trump. (…) Une chose est certaine : l’élection de Trump, mais aussi le Brexit, vont peser sur le langage et le lexique employés par une partie des prétendants à la présidentielle française. Des acteurs politiques, de droite comme de gauche, seront tentés de durcir leur discours. Mais ce climat chauffé à blanc devrait avant tout profiter à Marine Le Pen, la candidate du Front national. Personne ne fait mieux qu’elle dans ce registre. Dominique Reynié

Attention: un fiasco peut en cacher un autre !

Au lendemain de la victoire aussi reaganesque qu’inattendue du candidat républicain Donald Trump …

Et partant, à une ou deux exceptions près, d’un des plus grands fiascos de l’histoire sondagière …

Comment, comme le rappelle le politologue Dominique Reynié, ne pas voir …

Derrière cette revanche des « clingers » et « deplorables » si longtemps méprisés par un establishment prêt pour se maintenir en place à tous les coups tordus …

Et à l’instar du récent référendum du Brexit outre-manche comme de la qualification surprise du candidat frontiste au deuxième tour en France en 2002 …

La part du fameux effet Bradley …

A savoir la tendance de certains électeurs …

Dans un système de recueil de réponses téléphonique qui, option présentation du numéro oblige, n’atteint même pas les 15% …

Et des élections particulièrement atypiques où un candidat comme Trump peut brusquement donner voix à des millions de jusqu’ici non-votants …

Face à la démonisation généralisée – véritable terrorisme intellectuel – de leurs candidats par les médias et l’opinion en général …

A la dissimulation de leur intention de vote auprès des instituts de sondage ?

Dominique Reynié : «L’élection de Trump n’est pas une surprise»

Kevin Badeau

Les Echos

09/11/2016

LE CERCLE/INTERVIEW – Pour Dominique Reynié, directeur général de la Fondapol, les médias n’ont pas su entendre le malaise de la population américaine.

Donald Trump a été élu Président des Etats-Unis, est-ce vraiment une surprise ?

Les analystes politiques, les sondeurs et les journalistes ont donné à penser que la victoire d’Hillary Clinton était assurée avant l’élection. En cela, c’est une surprise, car la sphère médiatique n’imaginait pas la victoire du candidat républicain. Elle a eu tort. Si elle avait su observer la société américaine et entendre son malaise, elle n’aurait jamais exclu la possibilité d’une élection de Trump. Pour cette raison, ce n’est pas une surprise.

Pourquoi les médias n’ont-ils rien vu venir ?

Sans doute, ils ont rejeté Donald Trump car ils le trouvaient – et c’est le cas – démagogue, populiste et vulgaire. Je n’ai d’ailleurs jamais vu une élection américaine avec un tel parti pris médiatique. Même le très réputé hebdomadaire britannique « The Economist » a fait un clin d’oeil à Hillary Clinton.

Je pense que la stigmatisation sans précédent de Donald Trump par les médias a favorisé chez les électeurs américains la dissimulation de leur intention de vote auprès des instituts de sondage. En clair, un certain nombre de votants n’a pas osé admettre qu’il soutenait le candidat américain. Ce phénomène est classique en politique. Souvenez du 21 avril 2002 et de la qualification surprise de Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader du Front national, au second tour de l’élection présidentielle française.

L’élection de Donald Trump traduit-elle le refus de la mondialisation par les Américains ?

A travers l’élection de Trump, certains Américains ont exprimé leur colère. Une partie de l’Amérique ne trouve pas ses gains dans la globalisation. Cette Amérique-là ne parvient pas à retrouver son niveau de vie d’avant la crise des subprimes, elle a le sentiment d’être abandonnée. Ce sentiment était particulièrement perceptible chez les ouvriers, qui voient l’industrie s’effilocher. Ne se sentant pas assez considérés, ils ont davantage choisi Donald Trump qu’Hillary Clinton.

Est-ce une victoire du peuple américain contre l’establishment, comme on l’entend parfois ?

Cette formule est très exagérée. Oui, une partie des électeurs de Donald Trump ont voté contre Washington et ses élites. Oui, certains Américains souffrent d’un mépris de classe, en particulier dans l’Amérique profonde. Mais dire que le peuple s’est tourné vers Trump est inexact. Le candidat républicain et la candidate démocrate sont au coude à coude en termes de suffrages exprimés [à 15 heures, 47,5% pour Trump et 47,6% pour Clinton , NDLR]. Au passage, nous avons affaire à deux candidats richissimes. Si ma mémoire est bonne, Donald Trump, pseudo-candidat du peuple, n’est pas issu de la classe ouvrière…

Victor Orban en Hongrie, Andrzej Duda en Pologne, Trump aux Etats-Unis, pourquoi une telle vague populiste dans le monde occidental ?

L’arrivée au pouvoir de dirigeants populistes s’explique avant tout par des spécificités locales. Après, il y a des effets communs. De nouvelles puissances émergent. Les gens se sentent décentrés. Il y a une surabondance d’innovations technologiques et scientifiques. Une partie de la société se sent déclassée. L’immigration accélère les mécanismes de recomposition culturelle. Aux Etats-Unis, les Blancs anglo-saxons deviennent minoritaires. Ceci induit une réaction exprimée en votant pour un candidat populiste : Donald Trump.

L’élection de Trump est-elle une excellente nouvelle pour Marine Le Pen ?