I shouted out, Who killed the Kennedys? When after all It was you and me. The Rolling Stones (1968)

Il n’aura même pas eu la satisfaction d’être tué pour les droits civiques. Il a fallu que ce soit un imbécile de petit communiste. Cela prive même sa mort de toute signification. Jackie Kennedy

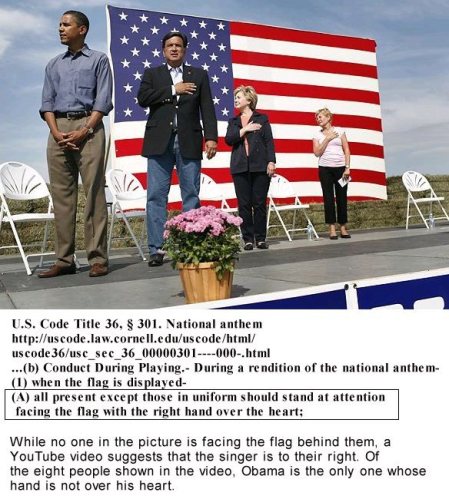

Oswald, un ancien marine de 20 ans, était arrivé en URSS en prétendant être marxiste. Selon Peter Savodnik, dont le livre The Interloper sur les années d’Oswald à Minsk a été publié plus tôt ce mois-ci, il disait qu’il avait des détails secrets sur le précieux avion espion américain U2. Le KGB n’était cependant pas impressionné et a d’abord rejeté sa demande, mais le jour où son visa touristique a expiré, Oswald s’est coupé les veines du poignet. Craignant un incident international s’il essayait à nouveau, les autorités soviétiques l’ont laissé rester. Ils l’envoyèrent à Minsk, capitale provinciale lointaine, qui aurait tout aussi bien pu être la Sibérie. Il s’est vu confier un emploi dans une usine de radio et de télévision et s’est vu attribuer un appartement d’une pièce dans le centre-ville. Oswald profitait de l’attention d’être l’un des rares étrangers de Minsk et son seul Américain. Il visitait régulièrement un foyer de jeunes filles, près de son appartement. (…) Le KGB gardait un œil sur Oswald, ayant mis son appartement sur écoute et percé un tout petit trou dans le mur pour enregistrer même ses moments les plus intimes. (…) Au début, le KGB pensait qu’il travaillait peut-être pour la CIA, et que ses tentatives maladroites d’apprendre le russe étaient de la simulation. (…) Savodnik dit qu’Oswald « se prenait pour un marxiste, un révolutionnaire » qui « défendait la cause ». Mais pour lui, la raison profonde de sa défection était « plus psychologique qu’idéologique ». « Je pense qu’il est parti là-bas parce qu’il ne s’intégrait nulle part, et c’était un jeune homme désespéré et solitaire, qui croyait trouver son salut en Russie ». David Stern

À partir de ses 15 ans, selon ses propres déclarations, Oswald s’intéresse au marxisme. Peu après, à La Nouvelle-Orléans, il achète le Capital et le Manifeste du Parti communiste. En octobre 1956, Lee écrit au président du Parti socialiste d’Amérique une lettre où il se déclare marxiste et affirme étudier les principes marxistes depuis quinze mois. Pourtant, alors même qu’il lit toute la littérature marxiste qu’il peut trouver, Oswald prépare son entrée dans les marines en apprenant par cœur le manuel des marines de son frère aîné, Robert, qui est marine. Oswald adore ce frère dont il porte fièrement la bague du Corps et rêve depuis longtemps de l’imiter en le suivant dans la carrière. Alors même qu’il se considère comme un marxiste, Oswald réalise son rêve d’enfance et s’engage dans les marines une semaine après son dix-septième anniversaire. Après les entraînements de base, d’octobre 1956 à mars 1957, Oswald suit un entraînement spécifique destiné à la composante aérienne des marines. Au terme de cet entraînement, le 3 mai 1957, il devient soldat de première classe, reçoit l’accréditation de sécurité minimale, « confidentiel », et suit l’entraînement d’opérateur radar. Après un passage à la base d’El Toro (Californie) en juillet 1957, il est assigné à la base d’Atsugi, au Japon, en août 1957. Cette base est utilisée pour les vols de l’avion espion Lockheed U-2 au-dessus de l’URSS, et quoique Oswald ne soit pas impliqué dans ces opérations secrètes, certains auteurs ont spéculé qu’il aurait pu commencer là une carrière d’espion. (…) En février 1959, il demande à passer un test de connaissance du russe auquel il a des résultats « faibles ». C’est alors qu’Oswald commence à exprimer de manière claire des opinions marxistes qui n’améliorent pas sa popularité auprès de ses camarades. Il lit énormément de revues en russe, écoute des disques en russe et s’adresse aux autres soit en russe soit en contrefaisant un accent russe. Ses camarades le surnomment alors « Oswaldskovich ». Mi-1959, il fait en sorte de rompre prématurément son engagement dans l’armée en prétextant le fait qu’il est le seul soutien pour sa mère souffrante. Lorsqu’il peut quitter l’armée en septembre 1959, il a en fait déjà préparé l’étape suivante de sa vie, sa défection en URSS. Oswald a été un bon soldat, en tout cas au début de sa carrière, et ses résultats aux tests de tir, par exemple, sont très satisfaisants. Ses résultats au tir se dégradent cependant vers la fin de sa carrière militaire, élément qui fut ensuite utilisé pour faire passer Oswald pour un piètre tireur. Ainsi, avec un score de 191 le 5 mai 1959, Oswald atteint encore le niveau « bon tireur », alors qu’il envisage déjà son départ du Corps. Lors de cette séance de tir, Nelson Delgado, la seule personne qui affirma devant la commission Warren qu’Oswald était un mauvais tireur, avait fait 192. En fait, selon les standards du Corps de Marines, Oswald était un assez bon tireur. Le voyage d’Oswald en URSS est bien préparé : il a économisé la quasi-totalité de sa solde de marine et obtient un passeport en prétendant vouloir étudier en Europe. Il embarque le 20 septembre 1959 sur un bateau en partance de La Nouvelle-Orléans à destination du Havre, où il arrive le 8 octobre pour partir immédiatement vers Southampton, puis prend un avion vers Helsinki (Finlande), où il atterrit le 10 octobre. Dès le lundi 12, Oswald se présente à l’ambassade d’URSS et demande un visa touristique de six jours dans le cadre d’un voyage organisé, visa qu’il obtient le 14 octobre. Oswald quitte Helsinki par train le 15 octobre et arrive à Moscou le 16. Le jour même, il demande la citoyenneté soviétique, que les Soviétiques lui refusent au premier abord, considérant que sa défection est de peu de valeur. Après qu’il a tenté de se suicider, les Soviétiques lui accordent le droit de rester, d’abord temporairement, à la suite de quoi Oswald tente de renoncer à sa citoyenneté américaine, lors d’une visite au consul américain le 31 octobre 1959, puis pour un temps indéterminé. Les Soviétiques envoient Oswald à Minsk en janvier 1960. Il y est surveillé en permanence par le KGB pendant les deux ans et demi que dure son séjour. Oswald semble tout d’abord heureux : il a un travail dans une usine métallurgique, un appartement gratuit et une allocation gouvernementale en plus de son salaire, une existence confortable selon les standards de vie soviétiques. Le fait que le U2 de Francis Powers ait été abattu par les Soviétiques après l’arrivée d’Oswald, en mai 1960, a éveillé la curiosité de certains auteurs se demandant quel lien cet évènement pouvait avoir avec le passage d’Oswald sur la base d’Atsugi, une des bases d’où des U2 décollaient. Cependant, outre qu’Oswald ne semble jamais avoir été en contact avec des secrets sur Atsugi, personne n’a jamais réussi à établir un lien entre Oswald et cet évènement. Ainsi, le U2 de Powers a été abattu par une salve de missiles SA-2 chanceuse (à moins que Powers ait été sous son plafond normal) et aucun renseignement spécial n’a été nécessaire à cet effet. (…) En mars 1961, alors qu’il a eu quelques contacts avec l’ambassade américaine à Moscou en vue de son retour aux États-Unis, Oswald rencontre Marina Nikolayevna Prusakova, une jeune étudiante en pharmacie de 19 ans, lors d’un bal au palais des Syndicats. Ils se marient moins d’un mois plus tard et s’installent dans l’appartement d’Oswald. Oswald a écrit plus tard dans son journal qu’il a épousé Marina uniquement pour faire du mal à son ex-petite amie, Ella Germain. En mai 1961, Oswald réitère à l’ambassade américaine son souhait de retourner aux États-Unis, cette fois avec son épouse. Lors d’un voyage en juillet à Moscou, Oswald va avec Marina, enceinte de leur premier enfant, à l’ambassade américaine pour demander un renouvellement de son passeport. Ce renouvellement est autorisé en juillet, mais la lutte avec la bureaucratie soviétique va durer bien plus longtemps. Lorsque le premier enfant des Oswald, June, naît en février 1962, ils sont encore à Minsk. Finalement, ils reçoivent leur visa de sortie en mai 1962, et la famille Oswald quitte l’URSS et embarque pour les États-Unis le 1er juin 1962. La famille Oswald s’installe à Fort Worth (près de Dallas) vers la mi-juin 1962, d’abord chez son frère Robert, ensuite chez sa mère, début juillet, et enfin dans un petit appartement fin juillet, lorsque Lee trouve un travail dans une usine métallurgique. Le FBI s’intéresse naturellement à Lee et provoque deux entretiens avec lui, le 26 juin et le 16 août. Les entretiens ne révélant rien de notable, l’agent chargé du dossier demande à Oswald de contacter le FBI si des Soviétiques le contactaient, et conclut ses rapports en recommandant de fermer le dossier. Cependant, dès le 12 août, Lee écrit au Socialist Workers Party, un parti trotskiste, pour leur demander de la documentation, et continue de recevoir trois périodiques russes. Vers la fin août, les Oswald sont introduits auprès de la petite communauté de Russes émigrés de Dallas. Ceux-ci n’aiment pas particulièrement Oswald, qui se montre désagréable, mais prennent en pitié Marina, perdue dans un pays dont elle ne connait même pas la langue que Lee refuse de lui apprendre. C’est dans le cadre de ces contacts qu’Oswald rencontre George de Mohrenschildt, un riche excentrique d’origine russe de 51 ans qui prend Oswald en sympathie. Les relations entre Oswald et Mohrenschildt ont été source de nombreuses spéculations, et certains ont cru voir dans Mohrenschildt un agent ayant participé à une conspiration, sans jamais trouver d’élément factuel qui démontre cette hypothèse. (…) En février 1963, alors que les relations entre Lee et Marina s’enveniment jusqu’à la violence, Oswald prend un premier contact avec l’ambassade d’URSS en laissant entendre qu’il souhaite y retourner. C’est aussi au cours de ce mois que les Oswald rencontrent Ruth Paine, qui allait devenir, avec son mari Michael, très proche des Oswald. Rapidement, Ruth et Marina deviennent amies au cours du mois de mars 1963, et c’est à la fin du mois que Lee demande à Marina de prendre des photos de lui avec ses armes. C’est également au cours de ce mois qu’Oswald commence à préparer l’assassinat du général Walker, que les deux armes commandées lui furent livrées, que Lee perdit son travail chez Jaggers et que l’agent Hosty du FBI commença un réexamen de routine du dossier de Oswald et Marina (six mois s’étant écoulés depuis son dernier entretien avec Oswald), au cours duquel il découvrit une note du FBI de New York sur un abonnement de Lee au Worker, journal communiste, ce qui l’intrigua et le poussa à rouvrir le dossier. Toutefois, avant que Hosty ait pu traiter le dossier, il se rendit compte que les Oswald avaient quitté Dallas. Le général Edwin Walker, un héros de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, est un anticommuniste virulent et partisan de la ségrégation raciale. Walker a été relevé de son commandement en Allemagne et muté à Hawaï en avril 1961 par le président Kennedy après qu’il eut distribué de la littérature d’extrême-droite à ses troupes. Il démissionne alors de l’armée en novembre 1961 et se retire à Dallas pour y commencer une carrière politique. Il se présente contre John Connally pour l’investiture démocrate au poste de gouverneur du Texas en 1962, mais est battu par Connally qui est finalement élu gouverneur. À Dallas, Walker devient la figure de proue de la John Birch Society, une organisation d’extrême-droite basée au Massachusetts. Walker représente tout ce que déteste Oswald et il commence à le surveiller en février 1963, prenant notamment des photos de son domicile et des environs. Le 10 avril 1963, alors qu’il est congédié de chez Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall depuis dix jours, il laisse une note en russe à Marina et quitte son domicile avec son fusil. Le soir même, alors que Walker est assis à son bureau, on tire sur lui d’une distance de 30 mètres. Walker survit par un simple coup de chance : la balle frappe le châssis en bois de la fenêtre et est déviée. Lorsqu’Oswald rentre chez lui, il est pâle et semble effrayé. Quand il dit à Marina ce qu’il vient de faire, elle lui fait détruire l’ensemble des documents qu’il a rassemblés pour préparer sa tentative d’assassinat, bien qu’elle conserve la note en russe. L’implication d’Oswald dans cette tentative ne sera connue des autorités qu’après la mort d’Oswald, lorsque cette note, ainsi qu’une photo de la maison de Walker, accompagnées du témoignage de Marina, leur parviendra. La balle récupérée dans la maison de Walker est trop endommagée pour permettre une analyse balistique, mais l’analyse de cette balle par activation neutronique par le HSCA permet de déterminer qu’elle a été produite par le même fabricant que la balle qui tua Kennedy. Sans emploi, Oswald confie Marina aux bons soins de Ruth Paine et part à La Nouvelle-Orléans pour trouver du travail. (…) Marina le rejoint le 10 mai. Oswald semble à nouveau malheureux de son sort, et quoiqu’il ait perdu ses illusions sur l’Union soviétique, il oblige Marina à écrire à l’ambassade d’URSS pour demander l’autorisation d’y retourner. Marina reçoit plusieurs réponses peu enthousiastes de l’ambassade, mais entretemps les espoirs d’Oswald se sont reportés sur Cuba et Fidel Castro. Il devient un ardent défenseur de Castro et décide de créer une section locale de l’association Fair Play for Cuba. Il consacre 22,73 dollars à l’impression de 1 000 tracts, 500 demandes d’adhésion et 300 cartes de membres pour Fair Play for Cuba et Marina signe du nom de « A.J. Hidell » comme président de la section sur une des cartes. (…) Il fait, le 5 août 1963, une tentative d’infiltration des milieux anti-castristes, et se présente comme un anticommuniste auprès de Carlos Bringuier , délégué à La Nouvelle-Orléans de l’association des étudiants cubains en proposant de mettre ses capacités de Marine au service des anti-castristes. (…) Oswald envisage de détourner un avion vers Cuba, mais Marina réussit à l’en dissuader, et l’encourage à trouver un moyen légal d’aller à Cuba. En l’absence de liaison entre les États-Unis et Cuba, Lee commence à envisager de passer par le Mexique. (…) Oswald est dans un bus reliant Houston à Laredo le 26 septembre, et continue ensuite vers Mexico. Là, il tente d’obtenir un visa vers Cuba, se présentant comme un défenseur de Cuba et de Castro, et en affirmant qu’il veut ensuite continuer vers l’URSS. L’ambassade lui refuse le visa s’il n’avait pas au préalable un visa soviétique. L’ambassade d’URSS, après avoir consulté Moscou, refuse le visa. Après plusieurs jours de va-et-vient entre les deux ambassades, Oswald rejeté et mortifié retourne à Dallas. (…) Michael Paine, le mari de Ruth, a une conversation politique avec Oswald et se rend compte que malgré sa désillusion à l’égard des régimes socialistes, il est encore un fervent marxiste qui pense que la révolution violente est la seule solution pour installer le socialisme. Pendant les semaines suivantes, la situation entre Marina et Lee se dégrade à nouveau, tandis que le FBI de Dallas s’intéresse à nouveau à Oswald du fait de son voyage à Mexico.(….) Marina découvre que Lee a à nouveau écrit à l’ambassade d’URSS, et qu’il s’est inscrit sous un faux nom à son logement, et ils se disputent au téléphone à ce sujet. Le 19 novembre, le Dallas Time Herald publie le trajet que le président Kennedy utilisera lors de la traversée de la ville. Comme Oswald a pour habitude de lire le journal de la veille qu’il récupère dans la salle de repos du TSBD, on présume qu’il a appris que le président passerait devant les fenêtres du TSBD le 20 ou le 21 novembre. Wikipedia

Le grand ennemi de la vérité n’est très souvent pas le mensonge – délibéré, artificiel et malhonnête – mais le mythe – persistant, persuasif et irréaliste. JFK

Mes concitoyens du monde: ne demandez pas ce que l’Amérique peut faire pour vous, mais ce qu’ensemble nous pouvons faire pour la liberté de l’homme. JFK

Que tous, amis comme ennemis, sachent dès aujourd’hui et en ce lieu que le flambeau a été passé à une nouvelle génération d’Américains, née en ce siècle, tempérée par les combats, disciplinée par une paix difficile et amère, fière de son héritage ancien, et qui refuse d’assister et de laisser place à la lente décomposition des droits de l’homme pour lesquels cette nation s’est toujours engagée, et pour lesquels nous nous engageons aujourd’hui dans notre pays et dans le monde entier. Que chaque nation, bienfaitrice ou malintentionnée, sache que nous paierons n’importe quel prix, que nous supporterons n’importe quel fardeau, que nous surmonterons n’importe quelle épreuve, que nous soutiendrons n’importe quel ami et que nous combattrons n’importe quel ennemi pour assurer la survie et la victoire de la liberté. Nous en faisons solennellement la promesse. (…) Si une société libre ne peut pas aider la multitude de personnes vivant dans la pauvreté, elle ne peut pas sauver la minorité de personnes plus aisées. (…) Ne bâtissons jamais de négociations sur la peur. Mais n’ayons jamais peur de négocier. (…) Nous n’accomplirons pas tout cela dans les cent premiers jours. Ni dans les mille premiers jours, ni sous ce gouvernement, ni même peut-être au cours de notre existence sur cette planète. Mais nous pouvons commencer. C’est entre vos mains, mes chers concitoyens, plus que dans les miennes, que reposera le succès ou l’échec final de notre entreprise. Depuis la fondation de notre nation, chaque génération d’Américains a dû témoigner de sa loyauté envers notre pays. Les jeunes Américains qui ont répondu à cet appel reposent dans le monde entier. Aujourd’hui, la trompette retentit de nouveau, non pas comme un appel aux armes, bien que nous ayons besoin d’armes, non pas comme un appel au combat, bien que nous ayons des combats à mener, mais comme un appel à porter le fardeau d’une longue lutte crépusculaire, année après année, « en s’abreuvant d’espoir et en faisant preuve de patience dans l’adversité », une lutte contre les ennemis communs de l’homme : la tyrannie, la pauvreté, la maladie et la guerre elle-même. Pouvons-nous constituer contre ces ennemis une grande alliance mondiale unissant Nord et Sud, Est et Ouest, en mesure d’assurer une vie plus féconde pour l’humanité tout entière ? Vous associerez-vous à cet effort historique ? Tout au long de l’histoire du monde, seules quelques générations ont été appelées à défendre la liberté lorsqu’elle était grandement menacée. Je ne recule pas devant cette responsabilité, je m’en réjouis. Je crois qu’aucun d’entre nous n’échangerait sa place contre celle d’un autre ou de n’importe quelle autre génération. L’énergie, la foi et le dévouement dont nous faisons preuve dans cette entreprise éclaireront notre pays et tous ceux qui le servent, et cette lueur peut réellement se diffuser au monde entier. Ainsi, mes chers compatriotes américains : ne demandez pas ce que votre pays peut faire pour vous, mais bien ce que vous pouvez faire pour votre pays. Mes chers concitoyens du monde : ne demandez pas ce que l’Amérique peut faire pour vous, mais ce qu’ensemble nous pouvons faire pour la liberté de l’homme. Enfin, que vous soyez citoyens d’Amérique ou citoyens du monde, exigez de nous autant de force et de sacrifices que nous vous en demandons. Avec une bonne conscience comme seule récompense, avec l’histoire pour juge ultime de nos actes, à nous de diriger ce pays que nous aimons, en demandant la bénédiction et l’aide de Dieu, tout en sachant qu’ici sur terre, son œuvre doit être la nôtre. J.F. Kennedy (discours d’investiture, 20 janvier 1961)

Vérités paradoxales : les taux d’imposition sont trop élevés, et les revenus fiscaux sont trop bas, de sorte que le moyen le plus sûr d’accroître ceux-ci est d’abaisser ceux-là. Baisser les impôts maintenant ce n’est pas risquer un déficit du budget, c’est bâtir une économie la plus prospère et la plus dynamique, de nature à nous valoir un budget en excédent. John F. Kennedy, 20 novembre 1962, conférence de presse du Président

Des taux d’imposition abaissés stimuleront l’activité économique, et relèveront ainsi les niveaux de revenus des particuliers et des entreprises, de sorte que dans les prochaines années ils créeront un flux de recettes pour le gouvernement fédéral non pas diminué, mais augmenté. John F. Kennedy, 17 Janvier 1963, Message annuel au Congrès à l’occasion du vote du budget 1964.

Dans l’économie d’aujourd’hui, la prudence et la responsabilité en matière d’impôts commandent une réduction de la fiscalité, même si elle accroît le déficit budgétaire – parce qu’une moindre pression fiscale est le meilleur moyen qui nous soit offert pour accroître les revenus. John F. Kennedy (21 janvier 1963, message annuel au Congrès, rapport économique du président)

Chaque dollar soustrait à l’impôt, qui est dépensé ou investi, créera un nouvel emploi et un nouveau salaire. Et ces nouveaux emplois et salaires créeront d’autres emplois et d’autres salaires, et plus de clients, et plus de croissance pour une économie américaine en plein expansion. John F. Kennedy (13 août 1962, rapport radiodiffusé et télévisé sur l’état de l’économie nationale)

Une baisse des impôts signifie un revenu plus élevé pour les familles, et des profits plus importants pour les entreprises, et un budget fédéral en équilibre. Chaque contribuable et sa famille auront davantage d’argent disponible après impôt pour s’acheter une nouvelle voiture, une nouvelle maison, de nouveaux équipements, pour la formation et l’investissement. Chaque chef d’entreprise peut garder à sa disposition un pourcentage plus élevé de ses profits pour accroître ses fonds propres ou pour mettre en œuvre l’expansion ou l’amélioration de son affaire. Et quand le revenu national est en croissance, le gouvernement fédéral, en fin de compte, se retrouvera avec des recettes accrues. John F. Kennedy (18 septembre 1963, message à la nation radiodiffusé et télévisé sur un projet de loi de réduction des impôts)

Notre système fiscal aspire dans le secteur privé de l’économie une trop grande part du pouvoir d’achat des ménages et des entreprise, et réduit l’incitation au risque, à l’investissement et à l’effort – et par là-même il tue dans l’œuf nos recettes et étouffe notre taux de croissance national. John F. Kennedy (24 janvier 1963, message au Congrès sur la réforme fiscale)

L’essentiel de ses promesses, en un mot, Barack Obama les a tenues. Et, pour qu’il tienne l’autre moitié, il faut et il suffit de lui confier le second mandat dont il disait, dès le premier jour, qu’il en aurait besoin pour pleinement réussir dans son entreprise. Je ne regrette pas, pour ma part, d’avoir, dès 2004, soit quatre ans avant sa première élection, pressenti le prodigieux destin de celui que je baptisai aussitôt le « Kennedy noir ». Pas de raisons d’être déçu ! L’espoir est là. Plus que jamais là. Et le combat continue. BHL

Liberals like crises, and one shouldn’t spoil them by handing them another on a silver salver. The kind of crisis that is approaching . . . is probably not their favorite kind, an emergency that presents an opportunity to enlarge government, but one that will find liberalism at a crossroads, a turning point. (…) Liberalism can’t go on as it is, not for very long. It faces difficulties both philosophical and fiscal that will compel it either to go out of business or to become something quite different from what it has been. Charles Kesler

The modern Democratic Party, the party of Obama, is about permanent division and permanent opposition. (…) Despite seven Democratic presidencies since FDR, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Harvard still grieves, « The system is rigged! » (…) How is it that this generation of Democrats, nearly 225 years after the Constitutional Convention, sees 21st century America at the precipice of tooth and claw? (…) The Obama Democrats are no longer the party of FDR, Truman, JFK or Clinton. All were combative partisans, but their view of the American system was fundamentally positive. The older Democratic Party grew out of the American labor experience of the early 20th century, which recognized its inevitable ties to the private sector. The systemically alienated Obama party more resembles the ancient anticapitalist syndicalist movements of continental Europe. In its 2008 primaries, the Democratic Party made a historic pivot. The center-left party of Bill and Hillary Clinton was overthrown by Barack Obama and the party’s « progressives, » the redesigned logo of the vestigial Democratic left. (…) While liberals owned the party apparatus, the left took control of its ideas. By 1990, liberal Harvard Law School was torn apart by a left-wing theory called critical legal studies, which condemned the American legal and economic system as . . . rigged. What binds Barack Obama, Elizabeth Warren, Sandra Fluke and the rest of the Charlotte roster is the belief, learned early on, that their politics has made them a perpetual band of American outsiders. (…) This is a party whose agenda is avenging slights, wrongs and the systemic theft of « our democracy. » For all this injustice, someone must be made to pay. How far all this is from the America called for in Lincoln’s first inaugural: « We must not be enemies. » (…) An Obama victory wouldn’t be just a defeat of the GOP. It would be a defeat of the post-World War II Democratic Party. And they know it. The progressive left has wanted to push Democratic liberalism over the cliff for decades. This is their best shot to get it done. Daniel Henninger (Sep. 2012)

Did the bullets that killed JFK hit another target — liberalism itself? Unlike JFK, not killing liberalism instantly but inflicting something else infinitely more damaging than sudden death? Or, as Tyrrell puts it, inflicting “a slow, but steady decline of which the Liberals have been steadfastly oblivious.” (…) By 1968 — five years after the death of JFK and in the last of the five years of the Johnson presidency — the number of “self-identified” conservatives began to climb. Sharply. The Liberal dominance Lionel Trilling had written about had gone, never to this moment to return. Routinely now in poll after poll that Tyrrell cites — and there are plenty of others he doesn’t have room to cite — self-identified liberals hover at about 20% of the American body politic. Outnumbered more than two-to-one by conservatives, with moderates bringing up the remainder in the middle. What happened in those five years after JFK’s death? (…) The attitude toward Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson that was evidenced by Kennedy’s liberal leaning staff, by the Washington Georgetown set, by Washington journalists — slowly seeped into the sinews of liberalism itself. (…) Slowly this contempt for the American people spread to institutions that were not government, manifesting itself in a thousand different ways. It infected the media, academe and Hollywood, where stars identified with middle-America like John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Bob Hope and Lucille Ball were eclipsed in the spotlight by leftists like Warren Beatty and Jane Fonda. The arms-linked peaceful civil rights protests led by Christian ministers like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr gave way to bombings and violent demonstrations against the Vietnam War led by snooty, well-educated white left-wing kids like Bill Ayers. The great American middle class — from which many of these educated kids had sprung — was trashed in precisely the fashion LBJ had been trashed. For accents, clothing styles, housing choices (suburbs and rural life were out) food, music, the love of guns, choice of cars, colleges, hair styles and more. Religion itself could not escape, Christianity to be mocked, made into a derisive laughingstock. The part of America between New York and California became known sneeringly as “flyover country. As time moved on, these attitudes hardened, taking on colors, colors derived from election night maps where red represented conservative, Republican or traditional candidates and blue became symbolic of homes to Liberalism. (…) Had John F. Kennedy been alive and well this week, celebrating his 95th birthday, one can only wonder whether liberalism would have survived with him. This is, after all, the president who said in cutting taxes that a “rising tide lifts all boats.” Becoming The favorite presidential example (along with Calvin Coolidge) of no less than Ronald Reagan on tax policy. This is, after all, the president who ran to the right of Richard Nixon in 1960 on issues of national security. In fact, many of those who voted for John F. Kennedy in 1960 would twenty years later vote for Ronald Reagan. One famous study of Macomb County, Michigan found 63% of Democrats in that unionized section of autoworker country voting for JFK in 1960. In 1980, same county, essentially the same Democrats — 66% voted for Reagan. The difference? Liberalism was dying. There is a term of political art for these millions of onetime JFK voters — a term used still today: Reagan Democrats. It is not too strong a statement to say that in point of political fact John F. Kennedy was the father of the Reagan Democrats. (…) Would he have sat silently as the liberal culture turned against the vast American middle and working blue collar class and its values, sending JFK voters into the arms of Republicans in seven out of twelve of the elections following his own? Would he have fought the subtle but distinct change of his famous inaugural challenge from “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” to what it has now become: “ask not what you can do for your country, ask what service your government can provide you?” We will never know. But there is every reason to believe, after all these decades, that, to use the title of JFK biographer William Manchester’s famous book, The Death of a President, brought another, quite unexpected death in its wake. The Death of Liberalism. Jeffrey Lord

To recall John F. Kennedy’s brief tenure as President is to be reminded of the distance that American liberalism has traveled since those days. His landmark domestic initiatives, passed with modest adjustments after his death, were a civil-rights bill and a major tax reduction to stimulate the economy. The civil-rights legislation is well known, but many have forgotten Kennedy’s across-the-board, 30-percent tax cut, with the highest rate falling from 91 percent to 65 percent—a measure that, two decades later, would inspire Ronald Reagan’s own tax-cutting agenda. Kennedy was, moreover, a sophisticated anti-Communist who understood the stakes at issue in the cold war. His inspiring inaugural address in 1961 was entirely about foreign policy and the challenge of Communism to freedom-loving peoples. As President, his most notable victory was achieved by confronting the Soviet Union over its missiles in Cuba and by forcing their removal. And he was nothing if not forthright in declaring America’s universal aims. “Let every nation know,” he famously announced in his inaugural address, “whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” America, he said in a speech to the Massachusetts legislature a week before he took office, was “a city upon a hill,” an example and a model for the entire world. Though now remembered for his liberal idealism, Kennedy was, in short, a representative instead of the era’s pragmatic liberalism: an advocate of practical reform at home and American strength abroad. With his bold rhetoric and confidence in problem-solving, he was in many ways the personification of an earlier era’s liberal hopes. Both in substance and in approach, he seemed to express the central principle of the reform tradition—namely, that progress was to be achieved not by the quixotic pursuit of ideals but by the application of rationality and knowledge to the problems of public life. Kennedy himself often spoke in these terms, pointing to ignorance and extremism as the twin enemies to be overcome. (…) Hence, when the word spread on November 22 that President Kennedy had been shot, the immediate and understandable reaction was that the assassin must be a right-wing extremist—an anti-Communist, perhaps, or a white supremacist. Such speculation went out immediately over the national airwaves, and it seemed to make perfect sense, echoed by the likes of John Kenneth Galbraith and Chief Justice Earl Warren, who said that Kennedy had been martyred “as a result of the hatred and bitterness that has been injected into the life of our nation by bigots.” It therefore came as a shock when the police announced later the same day that a Communist had been arrested for the murder, and when the television networks began to run tapes taken a few months earlier showing the suspected assassin passing out leaflets in New Orleans in support of Fidel Castro. Nor was Lee Harvey Oswald just any leftist, playing games with radical ideas in order to shock friends and relatives. Instead, he was a dyed-in-the-wool Communist who had defected to the Soviet Union and married a Russian woman before returning to the U.S. the previous year. One of the first of an evolving breed, Oswald had lately rejected the Soviet Union in favor of third-world dictators like Mao, Ho, and Castro. (…) From this perspective, it should not have been so jarring to learn that he was a casualty of the cold war. (…) Yet the Warren report was vigorously attacked soon after it appeared, and has been the subject of controversy ever since. (…) What, then, explains the resilience of such fanciful and conspiratorial thinking? Part of the answer surely lies in the enduring need of the Left to circumvent the most inconvenient fact about President Kennedy’s assassination—that he was killed by a Communist and probably for reasons related to left-wing ideology. If the case against Oswald can be clouded or denied, it opens up the possibility that Kennedy was killed by a more familiar villain, one of the many malignant forces on the Right. Yet the record suggests that the decisive and overriding factor behind Oswald’s various actions was ideology. The assassination of President Kennedy was hardly an isolated incident in his political odyssey from the Marine Corps to the Soviet Union and back to the United States. In the months leading up to the assassination, Oswald had tried to kill the ultra-conservative retired Army General Edwin A. Walker (his shot missed) with the same rifle that he later used to shoot President Kennedy; initiated an altercation with anti-Castro figures in New Orleans that led to his arrest; and visited the Cuban embassy in Mexico City where, while seeking permission to travel to Cuba, he issued a threat against the life of the President. Edward Jay Epstein (in Legend, 1978) and Jean Davison (in Oswald’s Game, 1983) suggest that Oswald shot President Kennedy in retaliation for the administration’s schemes to eliminate Castro. There is much about Oswald and the assassination that can now never be known for certain. Of one thing, however, there can be little doubt: there would never have been any serious talk about a conspiracy if President Kennedy had been shot by a right-wing figure whose guilt was established by the same evidence as condemned Oswald. Such an event would have been readily understood in terms of then prevailing assumptions about the dangers from the Right. Kennedy’s assassin, however, bolted onto the historical stage in violation of a script that many people had assimilated as the truth about America. Instead of adjusting their thinking accordingly, they strove to account for the discordance by taking refuge in conspiracy theories. (…) This idea, too—that the nation as a whole was finally to blame for the assassination—came to be repeated widely and incorporated into the public’s understanding of the event. Liberals in particular tended to see Kennedy’s death in this light, that is, as an outgrowth of a violent or extremist streak in the nation’s culture. (…) Something strangely similar to this act of mental contortion would occur five years later in response to the assassination in Los Angeles of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Once again, many pointed to a national culture of violence and extremism as the ultimate cause of the killing. Jacqueline Kennedy herself, according to several biographers, was sufficiently shocked by this second assassination in her family that she resolved to live abroad with her children. Yet Senator Kennedy was killed by a Palestinian Arab, Sirhan Sirhan, who had resolved to act when he heard Kennedy express support for Israel while campaigning for the presidency in California. Sirhan represented more the hatreds of the world from which he had emigrated than any impulse in American culture. (…) In projecting their own hopes on to Kennedy, liberals like Schlesinger and cultural radicals like Mailer were redefining liberalism more in terms of a posture than in terms of a coherent body of ideas about government and politics. This, too, would have consequences. Because Kennedy embodied sophistication, he was seen after his death as more “authentic” than such otherwise authentically liberal figures as Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, who labored for legislative victories but were otherwise hopelessly old-fashioned. In appearing to stand above and apart from the conventions of middle-class life, he was seen as having opened up possibilities for a different kind of politics, sparking impulses that would eventually be absorbed into the mainstream of liberal thought. Within a few years of Kennedy’s death, liberals had come to be more preoccupied with cultural issues—feminism, sexual freedom, gay rights—than with the traditional concerns that had animated Roosevelt, Truman, and Kennedy himself. Kennedy’s had been a unique balancing act, combining ardent patriotism with hip sophistication in a mix that could appeal both to traditional Americans and to the new cultural activists. After his death, these two groups divided into conflicting camps, thereby establishing the terms for the long-running culture war that continues today. As much as anything else, the immersion in cultural politics in the years following the assassination may have helped bring about the end of the liberal era. Kennedy’s assassination heralded a break with the American past and a corresponding rupture in the evolving world of liberal ideas. Far from spurring the liberal tradition forward, as some today still suggest, it played a significant role in its disintegration. In the years and decades that followed, nearly all of the tendencies of the far Right that had so unnerved the liberals of the 1950’s—the fascination with conspiracies, the use of overheated and abusive rhetoric to characterize political adversaries, expressions of hatred for the United States and its national culture—moved across the political spectrum to the far and then the near Left. For many American liberals, the shock of Kennedy’s death compromised their faith in the nation itself. Against all evidence, they concluded that a violent strain in our national culture was somehow to blame. A confident, practical, and forward-looking philosophy with a heritage of accomplishment was thus turned into a doctrine of pessimism and self-blame, with a decidedly dark view of American society. Such assumptions, far from marking a temporary adjustment to the events of the 1960’s, have proved remarkably durable. James Piereson

Qui se souvient aujourd’hui qu’Oswald était en fait un communiste qui voulait faire payer à JFK la tentative d’assassinat de Castro ?

Que Sirhan Sirhan était un Palestinien voulant faire payer à son frère son soutien à Israël ?

Que le « père des Reagan democrats » était à droite de Nixon pour la politique étrangère mais plutôt en économie un pragmatique à la Clinton ?

Au lendemain d’un second discours d’investiture où, derrière les flonflons oratoires (et un véritable festival de distorsions des textes fondateurs tant bibliques que constitutionnels du pays de sa mère) qui ont à nouveau tant réjoui nos beaux esprits et nos belles âmes, un prétendu « Kennedy noir » a montré son vrai visage d’implacable doctrinaire …

En ce cinquantenaire de sa disparition prématurée …

Et, à l’instar comme le montre la fortune continuée des théories du complot à la Oliver Stone de son incapacité à reconnaitre la réalité de son assassinat par un extrémiste de gauche, histoire de mesurer l’incroyable dérive de l’actuel parti démocrate …

Pendant qu’en France on n’a toujours pas pris la mesure des dérives des amis de nos propres porteurs de valises …

Retour avec deux articles de Commentary et de l’American Spectator (merci james) …

Sur le président qui en quelques courtes années avait incarné l’image d’un parti à la fois généreux et moderne (et le beau nom, perdu en français qui l’avait pourtant inventé, de « libéralisme« ) …

Mais aussi lancé, via les médias et ses successeurs dont le prétendu Kennedy noir actuel, une addiction au cool et une arrogance doctrinaire face au peuple qui finiraient par se révéler fatales …

Lee Harvey Oswald and the Liberal Crack-Up

James Piereson

Commentary

May 2006

Liberalism entered the 1960’s as the vital force in American politics, riding a wave of accomplishment running from the Progressive era through the New Deal and beyond. A handsome young president, John F. Kennedy, had just been elected on the promise to extend the unfinished agenda of reform. Liberalism owned the future, as Orwell might have said. Yet by the end of the decade, liberal doctrine was in disarray, with some of its central assumptions broken by the experience of the immediately preceding years. It has yet to recover.

What happened? There is, of course, a litany of standard answers, from the political to the cultural to the psychological, each seeking to explain the great upheaval summed up in that all-purpose phrase, “the 60’s.” To some, the relevant factor was a long overdue reaction to the repressions and pieties of 1950’s conformism. To others, the watershed event was the escalating war in Vietnam, sparking an opposition movement that itself escalated into widespread disaffection from received political ideas and indeed from larger American purposes. Still others have pointed to the simmering racial tensions that would burst into the open in riots and looting, calling into question underlying assumptions about the course of integration if not the very possibility of social harmony.

No doubt, the combination of these and other events had much to do with driving the nation’s political culture to the Left in the latter half of the decade. But there can be no doubt, either, that an event from the early 1960’s—namely, the assassination of Kennedy himself—contributed heavily. As many observers have noted, Kennedy’s death seemed somehow to give new energy to the more extreme impulses of the Left, as not only left-wing ideas but revolutionary leftist leaders—Marx, Lenin, Mao, Ho Chi Minh, and Castro among them—came in the aftermath to enjoy a greater vogue in the United States than at any other time in our history. By 1968, student radicals were taking over campuses and joining protest demonstrations in support of a host of extreme causes.

It is one of the ironies of the era that many young people who in 1963 reacted with profound grief to Kennedy’s death would, just a few years later, come to champion a version of the left-wing doctrines that had motivated his assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. But why should this have been so? What was it about mid-century liberalism that allowed it to be knocked so badly off balance by a single blow?

_____________

To recall John F. Kennedy’s brief tenure as President is to be reminded of the distance that American liberalism has traveled since those days. His landmark domestic initiatives, passed with modest adjustments after his death, were a civil-rights bill and a major tax reduction to stimulate the economy. The civil-rights legislation is well known, but many have forgotten Kennedy’s across-the-board, 30-percent tax cut, with the highest rate falling from 91 percent to 65 percent—a measure that, two decades later, would inspire Ronald Reagan’s own tax-cutting agenda.

Kennedy was, moreover, a sophisticated anti-Communist who understood the stakes at issue in the cold war. His inspiring inaugural address in 1961 was entirely about foreign policy and the challenge of Communism to freedom-loving peoples. As President, his most notable victory was achieved by confronting the Soviet Union over its missiles in Cuba and by forcing their removal. And he was nothing if not forthright in declaring America’s universal aims. “Let every nation know,” he famously announced in his inaugural address, “whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” America, he said in a speech to the Massachusetts legislature a week before he took office, was “a city upon a hill,” an example and a model for the entire world.

Though now remembered for his liberal idealism, Kennedy was, in short, a representative instead of the era’s pragmatic liberalism: an advocate of practical reform at home and American strength abroad. With his bold rhetoric and confidence in problem-solving, he was in many ways the personification of an earlier era’s liberal hopes. Both in substance and in approach, he seemed to express the central principle of the reform tradition—namely, that progress was to be achieved not by the quixotic pursuit of ideals but by the application of rationality and knowledge to the problems of public life. Kennedy himself often spoke in these terms, pointing to ignorance and extremism as the twin enemies to be overcome.

None of this was an accident of the moment; it had been building for a long time. During the 1950’s, thoughtful liberals had come to understand that they were no longer outsiders in American life; to the contrary, they had become the political establishment. Already in power for two extraordinarily eventful decades, they could take credit for the domestic experiments of the New Deal, the victory over fascism, and the creation of the post-war international order. By virtue of these achievements, liberalism had emerged as the nation’s public philosophy.

Though a doctrine of reform and progress, liberalism had thus begun to absorb some of the intellectual characteristics of conservatism: a due regard for tradition and continuity, a sense that progress must be built on the solid achievements of the past. More strikingly, liberals had come to see their most vocal domestic opponents as radicals—individuals and movements bent on undoing the established order. This challenge to the liberal establishment came not from the radical Left, however, but from the Right, in the form of anti-Communism, Christian fundamentalism, and racial and religious bigotry.

Adlai Stevenson, a favorite of liberals of the era, described during his 1952 presidential campaign the paradoxical situation that liberals now occupied:

The strange alchemy of time has somehow converted the Democrats into the truly conservative party in the country—the party dedicated to conserving all that is best and building solidly and safely on these foundations. The Republicans, by contrast, are behaving like the radical party—the party of the reckless and embittered, bent on dismantling institutions which have been built solidly into our social fabric.

_____________

The liberal movement was fortunate to have had during this time a group of formidable intellectual spokesmen, figures like Richard Hofstadter, Daniel Bell, Lionel Trilling, and David Riesman. Their persistent focus was on the dangers to the nation, as they saw them, arising from the American Right. In contrast to their Progressive and New Deal predecessors, who had thought mainly in terms of change, reform, and new policy, these writers thought more in terms of consolidating earlier gains, defending them against fresh challenges, and reconciling them with the broad tradition of American democracy.

In their view, the complaints of the Right derived not from groups in possession of competing status and authority but from those who felt weak and dispossessed by modern life. Bell referred to this collection of forces as the “radical Right,” a term he employed in the title of an influential book of essays that he edited on the subject in 1962. Hofstadter preferred the term “pseudo-conservative,” which he borrowed from Theodor Adorno, the German sociologist, to describe those “who employ the rhetoric of conservatism, [but] show signs of a serious and restless dissatisfaction with American life, traditions, and institutions. They have little in common with the temperate and compromising spirit of true conservatism in the classical sense of the word.”

These scholars saw the McCarthyites and religious fundamentalists of the 1950’s as only the most up-to-date expression of an enduring extremist impulse that had earlier produced the “Know-Nothings” in the 1850’s, the populists in the 1890’s, and the followers of Father Charles Coughlin or Huey Long in the 1930’s. Such movements, while arising out of different conditions, had certain features in common—in particular, the conviction that their people had been “sold out” by a conspiracy of Wall Street financiers, traitors in the government, or some other sinister group. As Bell put it in an essay in The Radical Right, “The theme of conspiracy haunts the mind of the radical rightist.”

This same thought was developed most memorably in Hofstadter’s 1964 book, The Paranoid Style in American Politics. Hofstadter was impressed not simply by the wilder statements emanating from the radical Right—for example, the claim by Joseph Welch of the John Birch Society that President Eisenhower was a Communist—but by a mode of argumentation that seemed to begin with feelings of persecution and conclude with a recital of grandiose plots against the nation and its way of life. Communist infiltration was, of course, a favored theme, but Hofstadter also cited paranoid fears about fluoride in the drinking water, efforts to control the sale of guns, federal aid to education, and other (usually) liberal initiatives of government. Important events, from this perspective, never happened through coincidence, circumstance, or the unfolding of complex processes; they were invariably the work of some unseen but all-powerful malevolent force.

_____________

In the months leading up to Kennedy’s assassination, violent acts committed by representatives of the radical Right did indeed seem to be escalating. In June 1963, the civil-rights leader Medgar Evers was shot and killed outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi. In September, a bomb was detonated at a black church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young girls. The Ku Klux Klan was linked to both crimes. In October, Adlai Stevenson, then the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, ventured to Dallas for a speech to commemorate “UN Day” and was met by demonstrators proclaiming “United States Day.” Heckled during his remarks, Stevenson was jostled and spat upon by protesters as he tried to depart and finally was struck over the head with a cardboard placard as he made his way to his car.

Seeming to fit into a pattern of right-wing violence, these events were easily absorbed into the explanatory structure of liberal thought. The melee in Dallas, meanwhile, gave Kennedy aides pause about the President’s planned trip to that city. Dallas, they feared, was a hotbed of the far Right and a dangerous place to visit.

Hence, when the word spread on November 22 that President Kennedy had been shot, the immediate and understandable reaction was that the assassin must be a right-wing extremist—an anti-Communist, perhaps, or a white supremacist. Such speculation went out immediately over the national airwaves, and it seemed to make perfect sense, echoed by the likes of John Kenneth Galbraith and Chief Justice Earl Warren, who said that Kennedy had been martyred “as a result of the hatred and bitterness that has been injected into the life of our nation by bigots.”

It therefore came as a shock when the police announced later the same day that a Communist had been arrested for the murder, and when the television networks began to run tapes taken a few months earlier showing the suspected assassin passing out leaflets in New Orleans in support of Fidel Castro. Nor was Lee Harvey Oswald just any leftist, playing games with radical ideas in order to shock friends and relatives. Instead, he was a dyed-in-the-wool Communist who had defected to the Soviet Union and married a Russian woman before returning to the U.S. the previous year. One of the first of an evolving breed, Oswald had lately rejected the Soviet Union in favor of third-world dictators like Mao, Ho, and Castro.

Informed later that evening of Oswald’s arrest, Mrs. Kennedy lamented bitterly that her husband had apparently been shot by this warped and misguided Communist. To have been killed by such a person, she felt, would rob his death of all meaning. Far better, she said, if, like Lincoln, he had been martyred for civil rights and racial justice.

Given her husband’s politics, Mrs. Kennedy’s comment might seem curious. For one thing, he had staked his presidency on mounting an aggressive challenge to Communism; for another, during his brief term in office the cold war had reached its most dangerous point in his confrontation with the Soviet Union over Cuba. From this perspective, it should not have been so jarring to learn that he was a casualty of the cold war. More significantly, however, the remark suggests that Mrs. Kennedy was already thinking about how President Kennedy’s legacy should be framed, and was sensing that the identity of the assassin might prove inconvenient in this regard.

_____________

Oswald was arrested, and later charged with the assassination, on the basis of solid evidence—all of it laid out in the Warren Commission report made public ten months later and, since then, in numerous television documentaries and in books like Gerald Posner’s Case Closed (1993).

Yet the Warren report was vigorously attacked soon after it appeared, and has been the subject of controversy ever since. There is little point in rehearsing the many criticisms of the commission’s work, nearly all of which question the conclusion that a single gunman was responsible for the assassination. These criticisms have been exhaustively answered in Posner’s book and in two comprehensive articles in COMMENTARY by Jacob Cohen.

1 Even Norman Mailer, in his own exhaustive study (Oswald’s Tale, 1995), concluded that Oswald was the probable assassin. Moreover, as Posner and Cohen point out, whatever difficulties attend the Warren report, they pale in comparison to those confronting the various conspiracy theories that have been offered as alternatives to the much-maligned “single bullet” theory of the Warren Commission.

What, then, explains the resilience of such fanciful and conspiratorial thinking? Part of the answer surely lies in the enduring need of the Left to circumvent the most inconvenient fact about President Kennedy’s assassination—that he was killed by a Communist and probably for reasons related to left-wing ideology. If the case against Oswald can be clouded or denied, it opens up the possibility that Kennedy was killed by a more familiar villain, one of the many malignant forces on the Right.

Thus, in JFK (1991), the filmmaker Oliver Stone, like his hero the New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, suggests that the assassination was engineered by governmental figures connected to the FBI or CIA. Some have insinuated that Lyndon Johnson was involved in the plot. Others have argued that Kennedy was the victim of a “hit” by organized crime in retaliation for his administration’s zealous prosecution of mob figures. All of these theorists have much in common with the archetypes of Hofstadter’s “paranoid style”: they begin their investigations with presumptions of conspiracy, and then arrange their facts to justify a pre-determined conclusion.

True, they are also responding to a key weakness in the Warren report, which, though taking full note of Oswald’s Communist sympathies and activities, played them down as motivations for killing President Kennedy. Oswald, the commission said, was driven by several factors, including a psychological “hostility to his environment,” failure to establish meaningful relationships with others, difficulties with his wife, perpetual discontent with the world around him, hatred of American society, a search for recognition and a wish to play a role in history, and, finally, his commitment to Marxism and Communism. This farrago of causes implies that Oswald was more a confused loner than a motivated ideologue. In the years and decades following the assassination, the American people would increasingly view the assassin in such terms.

Yet the record suggests that the decisive and overriding factor behind Oswald’s various actions was ideology. The assassination of President Kennedy was hardly an isolated incident in his political odyssey from the Marine Corps to the Soviet Union and back to the United States. In the months leading up to the assassination, Oswald had tried to kill the ultra-conservative retired Army General Edwin A. Walker (his shot missed) with the same rifle that he later used to shoot President Kennedy; initiated an altercation with anti-Castro figures in New Orleans that led to his arrest; and visited the Cuban embassy in Mexico City where, while seeking permission to travel to Cuba, he issued a threat against the life of the President. Edward Jay Epstein (in Legend, 1978) and Jean Davison (in Oswald’s Game, 1983) suggest that Oswald shot President Kennedy in retaliation for the administration’s schemes to eliminate Castro.

There is much about Oswald and the assassination that can now never be known for certain. Of one thing, however, there can be little doubt: there would never have been any serious talk about a conspiracy if President Kennedy had been shot by a right-wing figure whose guilt was established by the same evidence as condemned Oswald. Such an event would have been readily understood in terms of then prevailing assumptions about the dangers from the Right. Kennedy’s assassin, however, bolted onto the historical stage in violation of a script that many people had assimilated as the truth about America. Instead of adjusting their thinking accordingly, they strove to account for the discordance by taking refuge in conspiracy theories.

_____________

There was also another avenue of escape from the contradiction posed by the assassination. If one had to accept the fact that Oswald committed the deadly act, it was still possible to identify some broader cause that did not necessarily involve a conspiracy. Once again, Mrs. Kennedy instinctively hinted at such a cause in the grief-filled hours following the assassination. Jim Bishop (in The Day Kennedy Was Shot, 1972) reports that aboard Air Force One en route back to Washington, various people, including Lady Bird Johnson, had urged her to change out of the blood-spattered clothes she was still wearing. “No,” she replied more than once, “I want them to see what they have done.”

Who were “they”? The New York Times columnist James Reston supplied an answer of sorts in an article that appeared the next day under the title, “Why America Weeps: Kennedy Victim of Violent Streak He Sought to Curb in Nation.” Reston wrote:

America wept tonight, not alone for its dead young President, but for itself. The grief was general, for somehow the worst in the nation had prevailed over the best. The indictment extended beyond the assassin, for something in the nation itself, some strain of madness and violence, had destroyed the highest symbol of law and order.

The nation itself, Reston implied, was ultimately responsible for Oswald’s murderous act.

Returning to this theme two days later in an article suggestively titled “A Portion of Guilt for All,” Reston asserted that there was “a rebellion in the land against law and good faith, and . . . private anger and sorrow are not enough to redeem the events of the last few days.” He went on to cite a sermon delivered on November 24 by a Washington clergyman who, linking President Kennedy with Jesus, told his congregation that “We have been present at a new crucifixion. All of us had a part in the slaying of the President.”

This idea, too—that the nation as a whole was finally to blame for the assassination—came to be repeated widely and incorporated into the public’s understanding of the event. Liberals in particular tended to see Kennedy’s death in this light, that is, as an outgrowth of a violent or extremist streak in the nation’s culture. Yet doing so required its own species of doublethink, for the fact is that Oswald was not in any way a representative figure. He played no role in any domestic extremist movement. His radicalism was wholly un-American and anti-American. Even as a Communist or radical, he was sui generis. There was nothing about Oswald that even remotely reflected any broader pattern in American life.

Something strangely similar to this act of mental contortion would occur five years later in response to the assassination in Los Angeles of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Once again, many pointed to a national culture of violence and extremism as the ultimate cause of the killing. Jacqueline Kennedy herself, according to several biographers, was sufficiently shocked by this second assassination in her family that she resolved to live abroad with her children. Yet Senator Kennedy was killed by a Palestinian Arab, Sirhan Sirhan, who had resolved to act when he heard Kennedy express support for Israel while campaigning for the presidency in California. Sirhan represented more the hatreds of the world from which he had emigrated than any impulse in American culture.

_____________

Still another curiosity in the wake of the assassination was the transformation of the image of Kennedy himself. Though very much a characteristic liberal of his day, as we have seen, he came to be portrayed as a liberal hero of a very different sort—a leader who might have led the nation into a new age of peace, love, and understanding. Such a portrayal was encouraged by tributes and memorials inspired by friends and members of the Kennedy family as well as by the numerous books published after the assassination, particularly those by the presidential aides Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (A Thousand Days, 1965) and Theodore Sorensen (Kennedy, 1965).

The most potent element of this image-making was, of course, the now inescapable association of Kennedy with the legend of King Arthur and Camelot. This was the invention of Jacqueline Kennedy, who a week after her husband’s death pressed the idea upon the journalist Theodore H. White in the course of an interview that would serve as the basis for an article by him in Life magazine. White later regretted the role he had played in transmitting this romantic image to the public. “Quite inadvertently,” he wrote in his memoir, In Search of History (1978), “I was her instrument in labeling the myth.”

White’s short essay in Life contained a number of Mrs. Kennedy’s wistful remembrances, one of which was the President’s fondness for the title tune from the Lerner & Lowe Broadway hit, Camelot. His favorite lines, she told White, were these: “Don’t let it be forgot,/that once there was a spot,/for one brief shining moment/that was Camelot.” “There will be great Presidents again,” she continued, “but there will never be another Camelot again.” According to Mrs. Kennedy, her husband was an idealist who saw history as the work of heroes, and she wished to have his memory preserved in the form of appropriate symbols rather than in the dry and dusty books written by historians. Camelot was one such symbol; the eternal flame that she had placed on his grave was another.

Significantly, Mrs. Kennedy’s notion of Arthurian heroism derived not from Sir Thomas Mallory’s 15th-century classic Le Morte d’Arthur but from The Once and Future King (1958) by T.H. White (no relation to the journalist), on which the musical was based. White’s telling of the saga pokes fun at the pretensions of knighthood, pointedly criticizes militarism and nationalism, and portrays Arthur as a new kind of hero: an idealistic peacemaker seeking to tame the bellicose passions of his age. This may be one reason why Mrs. Kennedy’s effort to frame her husband’s legacy in this way was widely regarded as a distorted caricature of the real Kennedy and something he himself would have laughed at. Aides and associates reported that they had never heard Kennedy speak either about Camelot the musical or about its theme song. Some of Mrs. Kennedy’s friends said they had never even heard her speak about King Arthur or the play prior to the assassination.

According to Schlesinger, Mrs. Kennedy later thought she may have overdone this theme. Be that as it may, one has to give her credit for quick thinking in the midst of tragedy and grief—and also for injecting a set of ideas into the cultural atmosphere that would have large consequences. For not only did the Camelot reading of heroic public service cut liberalism off from its once-vigorous nationalist impulses but, if one accepted the image of a utopian Kennedy Camelot—and many did—then the best times were now in the past and would not soon be recovered. Life would go on, but America’s future could never match the magical chapter that had been brought to a premature end. Such thinking drew into question the no less canonical liberal assumption of steady historical progress, and compromised the liberal faith in the future.

Without intending to do so, Mrs. Kennedy had put forth an interpretation of her husband’s life and death that undercut mid-century liberalism at its core.

_____________

The success of the Kennedy myth bore still other troubling fruit for American liberalism. Kennedy had added something novel to the mix of our public life, skillfully managing to transcend his role as a politician to become a cultural figure in his own right—indeed, a celebrity. In this he was most unlike other prominent political figures of the time.

Kennedy was young and articulate; he wore his hair long; he sailed and played touch football; he consorted with Hollywood stars and Harvard professors; he was even something of an intellectual, speaking in measured cadences and having won (with the assistance of his father) a Pulitzer Prize for Profiles in Courage (1955). Above all, he was rich. His wife, moreover, was beautiful and glamorous; she wore French fashions and even spoke French (and Spanish, too). The two Kennedy children were every bit as photogenic as their parents. The American people had never seen anything like the Kennedys, except in the movies.

Kennedy was thus our first President and—with the partial exception of Bill Clinton—the only one so far successfully to marry the role of politician to that of cultural celebrity. Such a thing would never have occurred to Harry Truman or Franklin Roosevelt. As for Ronald Reagan, who moved in the opposite direction, out of the world of celebrity into politics, he never exercised the influence over that world that Kennedy did. Indeed, Kennedy’s earlier success in linking liberalism with celebrity was greatly responsible for turning Hollywood into the liberal-Left fortification that it is today.

Kennedy achieved this through a style that gave the appearance of a man at the cutting edge of new cultural trends, in contrast to other politicians (like Nixon or Eisenhower) who generally represented the established patterns and morals of middle-class life. In his memoir, Sorensen acknowledges that at the inauguration, Kennedy deliberately played up this purely stylistic contrast between himself and Eisenhower, his tired and aging predecessor. Schlesinger, for his part, sees in Kennedy’s style a substantive statement in itself: “His coolness was itself a new frontier. It meant freedom from the stereotyped responses of the past. . . . It offered hope for spontaneity in a country drowning in its own passivity.” Norman Mailer, the original “hipster,” saw Kennedy as an “existential hero,” a man who would courageously court death in quest of authentic experience.

But here is another curious twist. While Kennedy understood courage to involve facing down Communism or putting a man on the moon, Mailer was thinking in terms of what he called “a revolution in the consciousness of our time,” a goal (whether laudable or not) far beyond the capacity of any political leader to deliver. It is true that Kennedy cultivated a style—a style whose charms were magnified a thousandfold by the newly potent medium of television. But it is also obvious that many read far more into this style than was really there. Intellectuals, journalists, and significant cohorts of the college-educated young erroneously equated Kennedy’s style with a bohemian rejection of the blandness and conformity of middle-class life, when it in fact reflected the ways of the American aristocracy to which he and his wife belonged. (So, in a somewhat different way, did his relentless pursuit of sex and use of drugs.)

In projecting their own hopes on to Kennedy, liberals like Schlesinger and cultural radicals like Mailer were redefining liberalism more in terms of a posture than in terms of a coherent body of ideas about government and politics. This, too, would have consequences. Because Kennedy embodied sophistication, he was seen after his death as more “authentic” than such otherwise authentically liberal figures as Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, who labored for legislative victories but were otherwise hopelessly old-fashioned. In appearing to stand above and apart from the conventions of middle-class life, he was seen as having opened up possibilities for a different kind of politics, sparking impulses that would eventually be absorbed into the mainstream of liberal thought. Within a few years of Kennedy’s death, liberals had come to be more preoccupied with cultural issues—feminism, sexual freedom, gay rights—than with the traditional concerns that had animated Roosevelt, Truman, and Kennedy himself.

Kennedy’s had been a unique balancing act, combining ardent patriotism with hip sophistication in a mix that could appeal both to traditional Americans and to the new cultural activists. After his death, these two groups divided into conflicting camps, thereby establishing the terms for the long-running culture war that continues today. As much as anything else, the immersion in cultural politics in the years following the assassination may have helped bring about the end of the liberal era.

_____________

Kennedy’s assassination heralded a break with the American past and a corresponding rupture in the evolving world of liberal ideas. Far from spurring the liberal tradition forward, as some today still suggest, it played a significant role in its disintegration. In the years and decades that followed, nearly all of the tendencies of the far Right that had so unnerved the liberals of the 1950’s—the fascination with conspiracies, the use of overheated and abusive rhetoric to characterize political adversaries, expressions of hatred for the United States and its national culture—moved across the political spectrum to the far and then the near Left.

For many American liberals, the shock of Kennedy’s death compromised their faith in the nation itself. Against all evidence, they concluded that a violent strain in our national culture was somehow to blame. A confident, practical, and forward-looking philosophy with a heritage of accomplishment was thus turned into a doctrine of pessimism and self-blame, with a decidedly dark view of American society. Such assumptions, far from marking a temporary adjustment to the events of the 1960’s, have proved remarkably durable.

_____________

Footnotes

1 “Conspiracy Fever,” October 1975; “Yes, Oswald Alone Killed Kennedy,” June 1992.

Voir aussi:

JFK and the Death of Liberalism

Jeffrey Lord

The American Spectator

5.31.12

John F. Kennedy, the father of the Reagan Democrats, would have been 95 this week.

May 29th of this week marked John F. Kennedy’s 95th birthday.

Had he never gone to Dallas, had he the blessings of long years like his 105 year old mother Rose, the man immutably fixed in the American memory as a vigorous 40-something surely would be seen in an entirely different light.

If JFK were alive today?

Presuming his 1964 re-election, we would know for a fact what he did in Vietnam. We would know for a fact what a second-term Kennedy domestic program produced. And yes, yes, all those torrent of womanizing tales that finally gushed into headlines in the post-Watergate era (and still keep coming, the tale of White House intern Mimi Alford recently added to the long list) would surely have had a more scathing effect on his historical reputation had he been alive to answer them.

But he wasn’t.

As the world knows, those fateful few seconds in Dallas on November 22, 1963 not only transformed American and world history. They transformed JFK himself into an iconic American martyr, forever young, handsome and idealistic. Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of his assassination—and in spite of all the womanizing tales, in spite of the passage of now almost half a century—John F. Kennedy is still repeatedly ranked by Americans as among the country’s greatest presidents. In the American imagination, JFK is historically invincible

All of this comes to mind not simply as JFK’s 95th birthday came and went this week with remarkably little fanfare.

As readers of The American Spectator are well familiar, TAS founder and Editor-in-chief R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr. has a new book out in which he details The Death of Liberalism.

Once upon a time — in 1950 — Bob Tyrrell notes that the liberal intellectual Lionel Trilling could honestly open his book The Liberal Imagination with this sentence:

In the United States at this time Liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.

It was true in 1950 — and it was still true on the day John F. Kennedy’s motorcade began to make its way through the streets of Dallas.

It was still true a year later, when Kennedy’s successor Lyndon Johnson swamped the GOP’s conservative nominee Barry Goldwater.

But something had happened by 1964. Something Big. And it’s fair to wonder on the anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s 95th birthday if in fact that Something Big would ever have happened at all if Kennedy had not been in Lee Harvey Oswald’s gun sight that sunny November day almost 49 years ago.

In short, one wonders. Did the bullets that killed JFK hit another target — liberalism itself? Unlike JFK, not killing liberalism instantly but inflicting something else infinitely more damaging than sudden death? Or, as Tyrrell puts it, inflicting “a slow, but steady decline of which the Liberals have been steadfastly oblivious.”

While LBJ would ride herd on American liberalism for another year, in fact the dominant status of liberalism in both politics and culture that Trilling had observed in 1950 had, after JFK’s murder, curiously begun to simply fade. Not unlike Alice in Wonderland’s Cheshire cat, leaving nothing behind but a grin. Writes Tyrrell:

Yet Liberals, who began as the rightful heirs to the New Deal, have carried on as a kind of landed aristocracy, gifted but doomed.

The new book in Robert Caro’s biographical series, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power has received considerable attention for Caro’s detailed depiction of LBJ’s transition from powerful Senate Majority Leader to a virtual impotence as Kennedy’s vice president. But there’s a clue in this book as to the future decline of liberalism that is completely overlooked (and wasn’t published until after Tyrrell’s). A clue that revolves around the treatment of Vice President Johnson by Kennedy insiders and JFK’s Washington admirers — a treatment, it is important to note, that was never ever exhibited by JFK himself.

While Kennedy gave strict orders that LBJ was to be treated at all times with the respect due his office — and this was in an era when vice presidents customarily went unused by presidents, a fate that had befallen all vice presidential occupants from the nation’s first, John Adams, to Johnson — there was something else bubbling just below the surface in the Washington that was the Kennedy era.

Robert Caro describes it this way:

Washington had in many ways always been a small town, and in small towns gossip can be cruel, and the New Frontiersmen — casual, elegant, understated, in love with their own sophistication (“Such an in-group, and they let you know they were in, and you were not”, recalls Ashton Gonella) — were a witty bunch, and wit does better when it has a target to aim at, and the huge, lumbering figure of Lyndon Johnson, with his carefully buttoned-up suits and slicked-down hair, his bellowing speeches and extravagant, awkward gestures, made an inevitable target. “One can feel the hot breath of the crowd at the bullfight exulting as the sword flashes into the bull,” one historian wrote. In the Georgetown townhouses that were the New Frontier’s social stronghold “there were a lot of small parties, informal kinds, dinners that were given by Kennedy people for other Kennedy people. You know, twelve people in for dinner, all part of the Administration,” says United States Treasurer Elizabeth Gatov. “Really, it was brutal, the stories that they were passing, and the jokes and the inside nasty stuff about Lyndon.” When he mispronounced “hors d’oeuvres” as “whore doves,” the mistake was all over Georgetown in what seemed an instant.

Johnson’s Texas accent was mocked. His proclivity for saying “Ah reckon,” “Ah believe,” and saying the word “Negro” as “nigrah.” On one occasion of a white tie event at the White House, Caro writes of LBJ that “he wore, to the Kennedy people’s endless amusement, not the customary black tailcoat but a slate-gray model especially sent up by Dallas’ Neiman-Marcus department store.” The liberals populating the Kennedy administration and Washington itself were people with an affinity for words, and they began to bestow on Johnson — behind his back — nicknames such as “Uncle Cornpone” or “Rufus Cornpone.” Lady Bird Johnson was added to the game, and the Johnsons as a couple were nicknamed “Uncle Cornpone and his Little Pork Chop.”

None of this, Caro notes, was done by John Kennedy himself. JFK had an instinctive appreciation for Johnson’s sense of dignity, and he thought Lady Bird “neat.” This is, in retrospect, notable.

Why?