Quel récit collectif sommes-nous capables de mettre en avant qui puisse donner un sens au sacrifice de ces jeunes ? Et l’absence d’un tel récit – qui va au-delà du sens subjectif que chacun d’eux pouvait donner à l’éventualité de mourir au combat et que chacun assumait en s’engageant dans l’armée – dépossède les jeunes soldats tombés du sens de leur mort. Danièle Hervieu-Léger

Quel récit collectif sommes-nous capables de mettre en avant qui puisse donner un sens au sacrifice de ces jeunes ? Et l’absence d’un tel récit – qui va au-delà du sens subjectif que chacun d’eux pouvait donner à l’éventualité de mourir au combat et que chacun assumait en s’engageant dans l’armée – dépossède les jeunes soldats tombés du sens de leur mort. Danièle Hervieu-Léger

Je conteste le mot de guerre, je le conteste totalement. Hervé Morin (ministre français de la Défense)

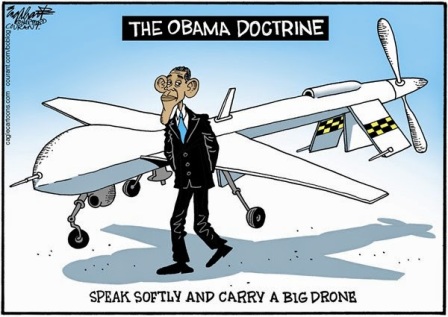

Avec un président qui se présente lui-même comme « normal », on s’attendait à revenir à moins d’emportement dans la gestion politico-médiatique de l’actualité, fut-elle dramatique comme l’est la mort de militaires français en Afghanistan. On pensait, naïvement sans doute, en avoir fini avec la manière du président Sarkozy, tout en vives colères et émotions sincères. Las ! C’est pire encore… (…) Bref, le chef de l’Etat donne à l’action d’un insurgé kamikaze un poids politique démesuré et envoie un message à tous les insurgés afghans : quatre morts français suffisent à bouleverser l’agenda des trois principaux personnages de l’Etat en charge de la défense ! Imagine-t-on Barack Obama dépêcher son secrétaire à la Défense en Afghanistan pour quatre morts ? Jean-Dominique Merchet

La résilience politique aux pertes, à distinguer de celle de l’ensemble de la nation en général plus forte) est de plus en plus faible (…) Cette très faible résilience politique induit une réticence de plus en plus marquée à l’engagement terrestre. Colonel Michel Goya (Irsem)

La France condamne l’action conduite contre Cheikh Ahmed Yassine qui a fait dix morts palestiniens comme elle a toujours condamné le principe de toute exécution extrajudiciaire, contraire au droit international. La pratique des exécutions extrajudiciaires viole les principes fondamentaux de l’Etat de droit sans lequel il n’y a pas de politique juste et efficace possible, y compris en matière de lutte contre le terrorisme. Cette pratique des forces armées israéliennes doit cesser. Au-delà de son caractère illégal, l’attaque d’hier risque d’être contre-productive au plan politique. Jean-Marc De La Sablière (représentant français à l’ONU, 2004)

Quand les drones frappent, ils ne voient pas les enfants. Faisal Shahzad (terroriste à la voiture piégée de Times Square)

Every time the American attacks increase, they increase the rage of the Yemeni people, especially in al-Qaeda-controlled areas. The drones are killing al-Qaeda leaders, but they are also turning them into heroes. Mohammed al-Ahmadi (avocat d’une ONG yéménite)

Un président américain ne devrait jamais hésiter à utiliser la force, même de manière unilatérale, pour protéger nos intérêts vitaux quand nous sommes attaqués ou sous le coup d’une menace imminente. Obama (Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 23.04.07)

Si nous avons des informations exploitables sur des cibles terroristes importantes et que le président Musharraf n’agit pas, nous le ferons. Obama (01.08.08)

Il ne faut pas confondre ‘procès équitable et ‘procédure judiciaire’, surtout lorsqu’il est question de sécurité nationale. La Constitution garantit le droit à un procès équitable, pas à une procédure judiciaire. Eric Holder (ministre de la Justice américain défendant les assassinats ciblés)

En une semaine, il est passé de Jane Fonda à Docteur Folamour. Mitt Romney

On September 30, 2011, a drone flying over Yemen set a new precedent. Without a trial or any public court proceeding, the United States government killed two American citizens, Anwar Al Awlaki and Samir Khan. The target of the attack was Awlaki, a New Mexico-born Yemeni-American whose charismatic preaching inspired terrorist attacks around the world, including the 2009 killing of 13 soldiers in Fort Hood, Texas. Civil liberties groups argued that a dangerous new threshold had been crossed. For the first time in American history, the United States had executed two of its citizens without trial. The Obama Administration cited a secret Justice Department memorandum as justification for the attack. Its authors contended that Awlaki’s killing was legal due to his role in attacks on the United States and his presence in an area where American forces could not easily capture him. David Rohde

After the global outrage over Guantánamo, it’s remarkable that the rest of the world has looked the other way while the Obama administration has conducted hundreds of drone strikes in several different countries, including killing at least some civilians. (…) It is the politically advantageous thing to do — low cost, no U.S. casualties, gives the appearance of toughness. (…) It plays well domestically, and it is unpopular only in other countries. Any damage it does to the national interest only shows up over the long term. Mr. Blair (ancien directeur du renseignement)

La popularité de ces aéronefs sans pilote n’est pas compliquée à comprendre. Ils ne sont pas chers, ils maintiennent les Américains hors des zones dangereuses et ils tuent ‘les méchants. Ils peuvent bien tuer des civils ou violer les lois, peu importe aux Américains. [Au contraire, cela] renforce son image d’homme (…) qui n’a pas peur d’utiliser la puissance américaine. Michael A. Cohen (Foreign Policy)

Qu’est donc devenu cet artisan de paix récompensé par un prix Nobel, ce président favorable au désarmement nucléaire, cet homme qui s’était excusé aux yeux du monde des agissements honteux de ces Etats-Unis qui infligeaient des interrogatoires musclés à ces mêmes personnes qu’il n’hésite pas aujourd’hui à liquider ? Il ne s’agit pas de condamner les attaques de drones. Sur le principe, elles sont complètement justifiées. Il n’y a aucune pitié à avoir à l’égard de terroristes qui s’habillent en civils, se cachent parmi les civils et n’hésitent pas à entraîner la mort de civils. Non, le plus répugnant, c’est sans doute cette amnésie morale qui frappe tous ceux dont la délicate sensibilité était mise à mal par les méthodes de Bush et qui aujourd’hui se montrent des plus compréhensifs à l’égard de la campagne d’assassinats téléguidés d’Obama. Charles Krauthammer

255 frappes au Pakistan, 38 au Yémen, 20 pour le seul mois d’avril (soit 6,5 fois plus que les 44 de Bush sans compter les 146 de Libye ou d’ailleurs), forces spéciales américaines dans 60 à 75 pays, attaques de drones dans pas moins de 5 pays étrangers (de l’Afghanistan à la Corne de l’Afrique), dommages collatéraux limités par nouvelle définition des impétrants (« tout individu d’âge militaire » y compris américain), liste secrète de cibles à liquider supervisée hebdomadairement et directement à la « cartes de baseball » par le président lui-même …

Attention: une campagne peut en cacher une autre!

A l’heure où, en cette journée de commémoration (nationale, s’il vous plait! – la guerre est-elle en train de devenir une affaire trop sérieuse pour la confier aux seuls politiques?) des quatre derniers soldats français tombés en Afghanistan…

Et entre les twits vengeurs de son actuelle compagne et les risques, avec l’éventualité de la fin de sa carrière politique suite à son élimination annoncée au 2e tour des législatives, de pétages de plomb de sa précédente …

Notre nouvelle Pleureuse en chef de l’Elysée (en voie – nouvelle promesse non tenue – de « peoplisation » avancée) qui se retrouve coincée entre sa promesse de campagne d’évacuer l’Afghanistan dès la fin de l’année puis de n’y maintenir que les « non-combattants » qui sont justement devenus les cibles de prédilection des talibans et de leurs infiltrés dans les troupes afghanes et son engagement de former lesdites troupes afghanes …

Pourrait bien se voir contraint de les confiner bien à l’abri sur leurs bases …

Retour avec une presse américaine qui nouvelle Belle au bois dormant semble brusquement se réveiller de son long et doux sommeil …

Sur le cruel dilemme d’un autre président, américain celui-là, coincé entre l’incroyable impunité, tant dans la presse que dans l’opinion nationale et internationale, dont bénéficie sa politique antiterroriste (si longtemps et violemment reprochée à Bush ou à ses inventeurs israéliens) lui permettant, à un coût modique en dollars et en vies de soldats américains mais au prix certes de l’abandon (sauf rares exceptions) de toute possibilité de collecter des informations et de susciter tant la haine des gouvernements et populations locales que des vocations terroristes, de ramener ainsi presque chaque jour son lot de terroristes abattus Ben Laden compris …

Et, avec l’impossibilité de compter sur son calamiteux bilan économique pour son éventuelle réélection dans quelques mois, la nécessité de justement faire parler – d’où les véritables fuites organisées actuelles – de la brillante réussite de ladite politique antiterroriste au risque (limité?) de voir la presse comme l’opinion prendre soudain conscience …

De l’existence, derrière l’actuelle campagne électorale pour la présidentielle de novembre (et, à défaut de la fermeture depuis si longtemps promise, l’impeccable appel au traitement humain des rares terroristes arrêtés), d’une véritable campagne d’assassinats ciblés orchestrée par leur héros lui-même.

Autrement dit que le plus rapide prix Nobel de la paix de l’histoire qu’ils avaient élu sur son éloquence d’artisan de la paix et surtout contre la prétendue brutalité de son prédécesseur …

Se trouve être en réalité, à l‘image du fameux Dr. Folamour de Kubrick dont on avait si souvent affublé le « cowboy Bush », « le président américain qui a approuvé le plus de frappes ciblées de toute l’histoire des Etats-Unis” …

Comment Obama a appris à tuer avec ses drones

Au fil de son premier mandat, c’est devenu la spécialité du président américain : sélectionner les terroristes à abattre et donner son aval à chaque frappe de drones à l’étranger. Une méthode expéditive qui suscite la polémique.

Jo Becker, Scott Shane

The New York Times

07.06.2012

traduit par Courrier international

Foreign Policy a consacré la une de son numéro daté de mars-avril aux “guerres secrètes d’Obama”. Qui aurait pu croire il y a quatre ans que le nom de Barack Obama allait être associé aux drones et à la guerre secrète technologique ? s’étonne le magazine, qui souligne qu’Obama “est le président américain qui a approuvé le plus de frappes ciblées de toute l’histoire des Etats-Unis”.

Voilà donc à quoi ressemblait l’ennemi : quinze membres présumés d’Al-Qaida au Yémen entretenant des liens avec l’Occident. Leurs photographies et la biographie succincte qui les accompagnait les faisaient ressembler à des étudiants dans un trombinoscope universitaire. Plusieurs d’entre eux étaient américains. Deux étaient des adolescents, dont une jeune fille qui ne faisait même pas ses 17 ans. Supervisant la réunion dédiée à la lutte contre le terrorisme, qui réunit tous les mardis une vingtaine de hauts responsables à la Maison-Blanche, Barack Obama a pris un moment pour étudier leurs visages. C’était le 19 janvier 2010, au terme d’une première année de mandat émaillée de complots terroristes dont le point culminant a été la tentative d’attentat évitée de justesse dans le ciel de Detroit le soir de Noël 2009. “Quel âge ont-ils ? s’est enquis Obama ce jour-là. Si Al-Qaida se met à utiliser des enfants, c’est que l’on entre dans une toute nouvelle phase.”

La question n’avait rien de théorique : le président a volontairement pris la tête d’un processus de “désignation” hautement confidentiel visant à identifier les terroristes à éliminer ou à capturer.

Obama a beau avoir fait campagne en 2008 contre la guerre en Irak et contre l’usage de la torture, il a insisté pour que soit soumise à son aval la liquidation de chacun des individus figurant sur une kill list [liste de cibles à abattre] qui ne cesse de s’allonger, étudiant méticuleusement les biographies des terroristes présumés apparaissant sur ce qu’un haut fonctionnaire surnomme macabrement les “cartes de base-ball”. A chaque fois que l’occasion d’utiliser un drone pour supprimer un terroriste se présente, mais que ce dernier est en famille, le président se réserve le droit de prendre la décision finale.

Liquider sans ciller

Rien, dans le premier mandat du président n’a autant déconcerté ses partisans de gauche ni autant consterné ses contempteurs conservateurs que cette implication directe dans la lutte contre le terrorisme.

Une série d’interviews accordées au New York Times par une trentaine de ses conseillers permettent de retracer l’évolution d’Obama depuis qu’il a été appelé à superviser personnellement cette “drôle de guerre” contre Al-Qaida et à endosser un rôle sans précédent dans l’histoire de la présidence américaine. Ils évoquent un chef paradoxal qui approuve des opérations de liquidation sans ciller, tout en étant inflexible sur la nécessité de circonscrire la lutte antiterroriste et d’améliorer les relations des Etats-Unis avec le monde arabe.

John Brennan, le conseiller pour le contre-terrorisme d’Obama, assiste le président dans ses moindres décisions. Certains de ses confrères le comparent à un limier traquant les terroristes depuis son bureau aux allures de cave installé dans les sous-sols de la Maison-Blanche ; d’autres à un curé dont la bénédiction serait devenue indispensable à Obama, en écho à la volonté du président d’appliquer la théorie des philosophes chrétiens de la “guerre juste” à un conflit moderne.

Mais les frappes qui ont décimé les rangs d’Al-Qaida – depuis le mois d’avril, au moins 14 de ses membres sont morts au Yémen et 6 au Pakistan – ont également mis à l’épreuve l’attachement des deux hommes à des principes dont ils ont martelé l’importance pour vaincre l’ennemi sur le long terme. Aujourd’hui, ce sont les drones qui suscitent des vocations terroristes, et non plus Guantánamo. Lorsqu’il a plaidé coupable en 2010, Faisal Shahzad – l’homme qui a tenté de faire exploser une voiture piégée à Times Square – a justifié le fait de s’en prendre à des civils en déclarant au juge : “Quand les drones frappent, ils ne voient pas les enfants.”

Un curieux rituel

C’est le plus curieux des rituels bureaucratiques : chaque semaine ou presque, une bonne centaine de membres du tentaculaire appareil sécuritaire des Etats-Unis se réunissent lors d’une visioconférence sécurisée pour éplucher les biographies des terroristes présumés et suggérer au président la prochaine cible à abattre. Ce processus de “désignation” confidentiel est une création du gouvernement Obama, un macabre “club de discussion” qui étudie soigneusement des diapositives PowerPoint sur lesquelles figurent les noms, les pseudonymes et le parcours de membres présumés de la branche yéménite d’Al-Qaida ou de ses alliés de la milice somalienne Al-Chabab.

Voir aussi:

Sa Majesté des drones à la Maison-Blanche

Le chroniqueur conservateur Charles Krauthammer condamne vigoureusement la stratégie de lutte contre le terrorisme adoptée par Obama. L’usage massif des drones est en totale contradiction avec l’image de droiture morale que le président affiche, estime-t-il.

Charles Krauthammer

The Washington Post

04.06.2012

Foreign Policy a consacré la une de son numéro daté de mars-avril aux “guerres secrètes d’Obama”. Qui aurait pu croire il y a quatre ans que le nom de Barack Obama allait être associé aux drones et à la guerre secrète technologique ? s’étonne le magazine, qui souligne qu’Obama “est le président américain qui a approuvé le plus de frappes ciblées de toute l’histoire des Etats-Unis”.

La lecture d’un récent article du New York Times portant sur la « petite activité hebdomadaire » du président a de quoi laisser pantois. On y apprend que tous les mardis Obama étale devant lui des cartes d’un genre très particulier où figurent les photos et les notices biographiques de terroristes présumés pour choisir quelle sera la prochaine victime d’une attaque de drone. Et c’est à lui qu’il revient de trancher : la probabilité de tuer un proche de la cible ou des civils se trouvant à proximité mérite-t-elle ou non d’interrompre la procédure ?

Cet article aurait pu s’intituler : « Barack Obama, Seigneur des drones ». On y apprend avec force détails comment Obama gère personnellement la campagne d’assassinats téléguidés. Et l’article fourmille de citations officielles des plus grands noms du gouvernement. Contrairement à ce que l’on pourrait croire, il ne s’agit pas de fuites mais bien d’un véritable communiqué de presse de la Maison-Blanche.

L’objectif est de présenter Obama comme un dur à cuire. Pourquoi maintenant ? Parce que, ces derniers temps, le locataire de la Maison-Blanche apparaît singulièrement affaibli : il semble impuissant alors que des milliers de personnes se font massacrer en Syrie ; il se fait rouler dans la farine par l’Iran comme en témoigne l’échec des dernières négociations sur le nucléaire à Bagdad ; Vladimir Poutine le traite avec mépris en bloquant toute intervention dans ces deux pays et lui a même infligé un camouflet public, en décidant de se faire remplacer [par son Premier ministre Medvedev] lors des derniers sommets du G8 et de l’Otan.

Le camp Obama pensait que l’exécution d’Oussama Ben Laden réglerait tous ses problèmes de politique étrangère. Mais la tentative par le gouvernement d’exploiter politiquement le premier anniversaire du raid meurtrier contre le chef d’Al-Qaida n’a pas eu les effets escomptés, bien au contraire. Après avoir abattu sa meilleure carte (la mort de Ben Laden), il lui fallait donc en trouver une nouvelle, et c’est là qu’intervient le « Seigneur des drones », un justicier solitaire, sans pitié pour les membres d’Al-Qaida.

Qu’est donc devenu cet artisan de paix récompensé par un prix Nobel, ce président favorable au désarmement nucléaire, cet homme qui s’était excusé aux yeux du monde des agissements honteux de ces Etats-Unis qui infligeaient des interrogatoires musclés à ces mêmes personnes qu’il n’hésite pas aujourd’hui à liquider ? L’homme de paix a été remplacé – juste à temps pour la campagne électorale de 2012 – par une sorte de dieu vengeur, toujours prêt à déchaîner son courroux.

Quel sens de l’éthique étrange. Comment peut-on se pavaner en affirmant que les Etats-Unis ont choisi la droiture morale en portant au pouvoir un président profondément offensé par le bellicisme et la barbarie de George W. Bush et ensuite révéler publiquement que votre activité préférée consiste à être à la fois juge et bourreau de combattants que vous n’avez jamais vus et que peu vous importe si des innocents se trouvent en leur compagnie.

Il ne s’agit pas de condamner les attaques de drones. Sur le principe, elles sont complètement justifiées. Il n’y a aucune pitié à avoir à l’égard de terroristes qui s’habillent en civils, se cachent parmi les civils et n’hésitent pas à entraîner la mort de civils. Non, le plus répugnant, c’est sans doute cette amnésie morale qui frappe tous ceux dont la délicate sensibilité était mise à mal par les méthodes de Bush et qui aujourd’hui se montrent des plus compréhensifs à l’égard de la campagne d’assassinats téléguidés d’Obama.

En outre le Seigneur des drones est un piètre stratège, car les terroristes morts ne peuvent pas parler. Les frappes aériennes de drones ne coûtent pas cher, ce qui est une bonne chose. Mais aller à la facilité a un coût. Ces attaques ne nous offrent aucune information sur les réseaux terroristes ni sur leurs projets. Capturer un seul homme pourrait être plus utile qu’en tuer dix. Le gouvernement Obama a révélé publiquement son opposition aux tribunaux militaires, sa volonté de juger Khalid Cheik Mohammed [considéré comme le cerveau des attentats du 11 septembre 2001] à New York et d’essayer vigoureusement (mais sans succès puisque, ô surprise, il n’y a pas d’autres solutions) de fermer Guantanamo Bay. Et pourtant ces délicates attentions à l’égard des terroristes quand ils sont prisonniers coexistent avec une volonté de les tuer directement dans leur lit.

Les prisonniers ont des droits, alors ne faisons pas de prisonniers, il y a là une morale perverse. Nous n’hésitons pas à tuer des terroristes, mais nous renonçons délibérément à obtenir des informations qui pourraient sauver des vies. Mais cela nous y penserons plus tard. Pour l’instant, réjouissons-nous de la haute stature morale et de l’absence de complaisance de notre Seigneur des drones présidentiel.

Non, la raison d’Etat américaine ne justifie pas tout?

Pour le San Francisco Chronicle, Obama a tort de suivre la ligne de son prédécesseur George W. Bush.

San Francisco Chronicle

15.03.2012

Pour Eric Holder, notre ministre de la Justice, il est légal de tuer à l’étranger des Américains soupçonnés de terrorisme sans procéder à un contrôle de constitutionnalité ni en informer l’opinion. Voilà une étonnante affirmation et une position bien révoltante de la part du gouvernement Obama, arrivé au pouvoir avec la promesse de revenir sur ce genre d’excès qui mettent à mal la Constitution.

Dans un discours prononcé devant des étudiants de la faculté de droit de la Northwestern University de Chicago, Eric Holder s’est essentiellement retranché derrière l’argument du “Faites-nous confiance” pour défendre ces assassinats ciblés. Les directives sont pourtant bien troubles : l’armée établira une liste de dangereux terroristes, y compris américains, les traquera et, si le pays où se trouve le suspect ne peut pas ou ne veut pas s’en occuper, les Etats-Unis s’en chargeront. L’exemple de référence est celui d’Anwar Al-Awlaki, l’imam d’Al-Qaida natif de l’Etat du Nouveau-Mexique tué en septembre dernier au Yémen par une frappe de drone.

Dans le cadre fixé par le ministre de la Justice, il n’y a ni examen extérieur, ni décision de justice, ni information justifiant la présence de tel ou tel suspect sur cette liste noire. Aux esprits chagrins attachés au contrôle et au cadre légal Eric Holder a offert cet éclaircissement : “Il ne faut pas confondre ‘procès équitable et ‘procédure judiciaire’, surtout lorsqu’il est question de sécurité nationale. La Constitution garantit le droit à un procès équitable, pas à une procédure judiciaire.”

Contrairement à ce qu’il avait promis, Obama n’a toujours pas fermé le goulag de Guantanamo, et voilà aujourd’hui qu’il s’oppose à une vraie transparence à propos des assassinats ciblés. Ce mépris de l’Etat de droit de la part de l’exécutif était intolérable du temps de George W. Bush ; il ne l’est pas moins sous Barack Obama.

Charles Krauthammer

The Washington Post

June 1, 2012

A very strange story, that 6,000-word front-page New York Times piece on how, every Tuesday, Barack Obama shuffles “baseball cards” with the pictures and bios of suspected terrorists from around the world and chooses who shall die by drone strike. He even reserves for himself the decision of whether to proceed when the probability of killing family members or bystanders is significant.

The article could have been titled “Barack Obama: Drone Warrior.” Great detail on how Obama personally runs the assassination campaign. On-the-record quotes from the highest officials. This was no leak. This was a White House press release.

Why? To portray Obama as tough guy. And why now? Because in crisis after recent crisis, Obama has looked particularly weak: standing helplessly by as thousands are massacred in Syria; being played by Iran in nuclear negotiations, now reeling with the collapse of the latest round in Baghdad; being treated with contempt by Vladimir Putin, who blocks any action on Syria or Iran and adds personal insult by standing up Obama at the latter’s G-8 and NATO summits.

The Obama camp thought that any political problem with foreign policy would be cured by the Osama bin Laden operation. But the administration’s attempt to politically exploit the raid’s one-year anniversary backfired, earning ridicule and condemnation for its crude appropriation of the heroic acts of others.

A campaign ad had Bill Clinton praising Obama for the courage of ordering the raid because, had it failed and Americans been killed, “the downside would have been horrible for him. “ Outraged vets released a response ad, pointing out that it would have been considerably more horrible for the dead SEALs.

That ad also highlighted the many self-references Obama made in announcing the bin Laden raid: “I can report . . . I directed . . . I met repeatedly . . . I determined . . . at my direction . . . I, as commander in chief,” etc. ad nauseam. (Eisenhower’s announcement of the D-Day invasion made not a single mention of his role, whereas the alternate statement he’d prepared had the landing been repulsed was entirely about it being his failure.)

Obama only compounded the self-aggrandizement problem when he spoke a week later about the military “fighting on my behalf.”

The Osama-slayer card having been vastly overplayed, what to do? A new card: Obama, drone warrior, steely and solitary, delivering death with cool dispatch to the rest of the al-Qaeda depth chart.

So the peacemaker, Nobel laureate, nuclear disarmer, apologizer to the world for America having lost its moral way when it harshly interrogated the very people Obama now kills, has become — just in time for the 2012 campaign — Zeus the Avenger, smiting by lightning strike.

A rather strange ethics. You go around the world preening about how America has turned a new moral page by electing a president profoundly offended by George W. Bush’s belligerence and prisoner maltreatment, and now you’re ostentatiously telling the world that you personally play judge, jury and executioner to unseen combatants of your choosing and whatever innocents happen to be in their company.

This is not to argue against drone attacks. In principle, they are fully justified. No quarter need be given to terrorists who wear civilian clothes, hide among civilians and target civilians indiscriminately. But it is to question the moral amnesia of those whose delicate sensibilities were offended by the Bush methods that kept America safe for a decade — and who now embrace Obama’s campaign of assassination by remote control.

Moreover, there is an acute military problem. Dead terrorists can’t talk.

Drone attacks are cheap — which is good. But the path of least resistance has a cost. It yields no intelligence about terror networks or terror plans.

One capture could potentially make us safer than 10 killings. But because of the moral incoherence of Obama’s war on terror, there are practically no captures anymore. What would be the point? There’s nowhere for the CIA to interrogate. And what would they learn even if they did, Obama having decreed a new regime of kid-gloves, name-rank-and-serial-number interrogation?

This administration came out opposing military tribunals, wanting to try Khalid Sheik Mohammed in New York, reading the Christmas Day bomber his Miranda rights and trying mightily (and unsuccessfully, there being — surprise! — no plausible alternative) to close Guantanamo. Yet alongside this exquisite delicacy about the rights of terrorists is the campaign to kill them in their beds.

You festoon your prisoners with rights — but you take no prisoners. The morality is perverse. Which is why the results are so mixed. We do kill terror operatives, an important part of the war on terror, but we gratuitously forfeit potentially life-saving intelligence.

But that will cost us later. For now, we are to bask in the moral seriousness and cool purpose of our drone warrior president.

Obama loses veneer of deniabilty with intelligence leaks

Richard Cohen

The Washington Post

June 12, 2012

Pity the poor Obama administration leakers. They impart their much-cherished secrets to make their man look good and then, at the first chirp of criticism, are ordered to confess their (possible) crimes by the very same president they were seeking to please. In this, they are a bit like the male praying mantis. He does as asked, and then the female bites his head off.

What is remarkable about the recent leaks is the coincidence — it can only be that — that they all made the president look good, heroic, decisive, strong and even a touch cruel; born, as the birthers long suspected, not in Hawaii — but possibly on the lost planet Krypton. The leak that displayed all these Obamian attributes was the one that said the president personally approves the assassinations of terrorists abroad. He gives his okay, and the bad guys are dispatched via missiles from drones.

The New York Times, which broke this particular story, said it had interviewed “three dozen of [Obama’s] current and former advisers,” which suggests the sort of mass law-breaking not seen since Richard Nixon took out after commies, liberals, conservationists, antiwar protesters, Jews and, of course, leakers. The two U.S. attorneys assigned to finding the leakers may have to use the facilities at Guantanamo, which, as luck would have it, are somehow still open. Of course, the chances of a successful prosecution are slim, leak cases being hard to prove. Journalists, unlike the mob, still adhere to the Mafia code of silence, omertà. We are, at heart, traditionalists.

All administrations leak what they want when they want. Occasionally, some killjoy screams something about national security, but the republic somehow survives and the secret is usually only a secret to the American people, not to the enemy. This is undoubtedly the case with the recent disclosure regarding the use of a computer worm to wreak havoc with the Iranian nuclear program. The Iranians were onto it.

The leak that troubles me concerns the killing of suspected or actual terrorists. The triumphalist tone of the leaks — the Tarzan-like chest-beating of various leakers — not only is in poor taste but also shreds a long-standing convention that, in these matters, the president has deniability. The president of the United States is not the Godfather.

Of course, we have always known that the president, as commander in chief and all of that, is where the proverbial buck stops. But for the longest time, a polite fiction distanced the president from what, after all, is murder, and it helped somewhat in protecting him. Deniability is always a fiction, but it provides some space between the president and his orders, and does not plaster the presidential face on an act of extreme — and possibly illegal — violence. Presidents need protection from retaliation — not just in office, but for the rest of their lives. After all, the poor man’s drone is the suicide bomber.

The present and former government officials who leaked to the Times as well as to Newsweek’s Daniel Klaidman are forgiven if they thought they were doing the boss’ bidding. After all, the president was serenely mum when the stories first hit. The White House did not react until some pesky Republicans, the reliably outraged John McCain in particular, yelled bloody murder. The leakers had to have noted that a torrent of leaks followed the killing of Osama bin Laden, with Obama characterized as just this side of personally dispatching the man with a butter knife. The Times’ David Sanger reports that the bragging got to the point that then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates told national security adviser Tom Donilon to “shut the [expletive] up.” Pakistan, it turns out, did not want its nose rubbed in its failure to notice bin Laden living in Abbottabad — or, for that matter, the SEALs coming to get him.

Killing is a serious matter. The death of an American citizen (Anwar al-Awlaki) is deeply troubling (the government asked the government if it was legal, and the government said it was). For this as well as other assassinations, there could be blowback.

Assassination by drone has its charms — it has severely degraded al-Qaeda — and war, after all, is war. But I wonder if those presidents who knew war — a Truman, an Eisenhower, a Kennedy — would themselves boast about killing or let others do it for them. The leakers set out to blow a mighty trumpet for Obama. It came out, however, like a shrill penny whistle.

Secret ‘Kill List’ Proves a Test of Obama’s Principles and Will

Jo Becker and Scott Shane

The New York Times

May 29, 2012

WASHINGTON — This was the enemy, served up in the latest chart from the intelligence agencies: 15 Qaeda suspects in Yemen with Western ties. The mug shots and brief biographies resembled a high school yearbook layout. Several were Americans. Two were teenagers, including a girl who looked even younger than her 17 years.

President Obama, overseeing the regular Tuesday counterterrorism meeting of two dozen security officials in the White House Situation Room, took a moment to study the faces. It was Jan. 19, 2010, the end of a first year in office punctuated by terrorist plots and culminating in a brush with catastrophe over Detroit on Christmas Day, a reminder that a successful attack could derail his presidency. Yet he faced adversaries without uniforms, often indistinguishable from the civilians around them.

“How old are these people?” he asked, according to two officials present. “If they are starting to use children,” he said of Al Qaeda, “we are moving into a whole different phase.”

It was not a theoretical question: Mr. Obama has placed himself at the helm of a top secret “nominations” process to designate terrorists for kill or capture, of which the capture part has become largely theoretical. He had vowed to align the fight against Al Qaeda with American values; the chart, introducing people whose deaths he might soon be asked to order, underscored just what a moral and legal conundrum this could be.

Mr. Obama is the liberal law professor who campaigned against the Iraq war and torture, and then insisted on approving every new name on an expanding “kill list,” poring over terrorist suspects’ biographies on what one official calls the macabre “baseball cards” of an unconventional war. When a rare opportunity for a drone strike at a top terrorist arises — but his family is with him — it is the president who has reserved to himself the final moral calculation.

“He is determined that he will make these decisions about how far and wide these operations will go,” said Thomas E. Donilon, his national security adviser. “His view is that he’s responsible for the position of the United States in the world.” He added, “He’s determined to keep the tether pretty short.”

Nothing else in Mr. Obama’s first term has baffled liberal supporters and confounded conservative critics alike as his aggressive counterterrorism record. His actions have often remained inscrutable, obscured by awkward secrecy rules, polarized political commentary and the president’s own deep reserve.

In interviews with The New York Times, three dozen of his current and former advisers described Mr. Obama’s evolution since taking on the role, without precedent in presidential history, of personally overseeing the shadow war with Al Qaeda.

They describe a paradoxical leader who shunned the legislative deal-making required to close the detention facility at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, but approves lethal action without hand-wringing. While he was adamant about narrowing the fight and improving relations with the Muslim world, he has followed the metastasizing enemy into new and dangerous lands. When he applies his lawyering skills to counterterrorism, it is usually to enable, not constrain, his ferocious campaign against Al Qaeda — even when it comes to killing an American cleric in Yemen, a decision that Mr. Obama told colleagues was “an easy one.”

His first term has seen private warnings from top officials about a “Whac-A-Mole” approach to counterterrorism; the invention of a new category of aerial attack following complaints of careless targeting; and presidential acquiescence in a formula for counting civilian deaths that some officials think is skewed to produce low numbers.

The administration’s failure to forge a clear detention policy has created the impression among some members of Congress of a take-no-prisoners policy. And Mr. Obama’s ambassador to Pakistan, Cameron P. Munter, has complained to colleagues that the C.I.A.’s strikes drive American policy there, saying “he didn’t realize his main job was to kill people,” a colleague said.

Beside the president at every step is his counterterrorism adviser, John O. Brennan, who is variously compared by colleagues to a dogged police detective, tracking terrorists from his cavelike office in the White House basement, or a priest whose blessing has become indispensable to Mr. Obama, echoing the president’s attempt to apply the “just war” theories of Christian philosophers to a brutal modern conflict.

But the strikes that have eviscerated Al Qaeda — just since April, there have been 14 in Yemen, and 6 in Pakistan — have also tested both men’s commitment to the principles they have repeatedly said are necessary to defeat the enemy in the long term. Drones have replaced Guantánamo as the recruiting tool of choice for militants; in his 2010 guilty plea, Faisal Shahzad, who had tried to set off a car bomb in Times Square, justified targeting civilians by telling the judge, “When the drones hit, they don’t see children.”

Dennis C. Blair, director of national intelligence until he was fired in May 2010, said that discussions inside the White House of long-term strategy against Al Qaeda were sidelined by the intense focus on strikes. “The steady refrain in the White House was, ‘This is the only game in town’ — reminded me of body counts in Vietnam,” said Mr. Blair, a retired admiral who began his Navy service during that war.

Mr. Blair’s criticism, dismissed by White House officials as personal pique, nonetheless resonates inside the government.

William M. Daley, Mr. Obama’s chief of staff in 2011, said the president and his advisers understood that they could not keep adding new names to a kill list, from ever lower on the Qaeda totem pole. What remains unanswered is how much killing will be enough.

“One guy gets knocked off, and the guy’s driver, who’s No. 21, becomes 20?” Mr. Daley said, describing the internal discussion. “At what point are you just filling the bucket with numbers?”

‘Maintain My Options’

A phalanx of retired generals and admirals stood behind Mr. Obama on the second day of his presidency, providing martial cover as he signed several executive orders to make good on campaign pledges. Brutal interrogation techniques were banned, he declared. And the prison at Guantánamo Bay would be closed.

What the new president did not say was that the orders contained a few subtle loopholes. They reflected a still unfamiliar Barack Obama, a realist who, unlike some of his fervent supporters, was never carried away by his own rhetoric. Instead, he was already putting his lawyerly mind to carving out the maximum amount of maneuvering room to fight terrorism as he saw fit.

It was a pattern that would be seen repeatedly, from his response to Republican complaints that he wanted to read terrorists their rights, to his acceptance of the C.I.A.’s method for counting civilian casualties in drone strikes.

The day before the executive orders were issued, the C.I.A.’s top lawyer, John A. Rizzo, had called the White House in a panic. The order prohibited the agency from operating detention facilities, closing once and for all the secret overseas “black sites” where interrogators had brutalized terrorist suspects.

“The way this is written, you are going to take us out of the rendition business,” Mr. Rizzo told Gregory B. Craig, Mr. Obama’s White House counsel, referring to the much-criticized practice of grabbing a terrorist suspect abroad and delivering him to another country for interrogation or trial. The problem, Mr. Rizzo explained, was that the C.I.A. sometimes held such suspects for a day or two while awaiting a flight. The order appeared to outlaw that.

Mr. Craig assured him that the new president had no intention of ending rendition — only its abuse, which could lead to American complicity in torture abroad. So a new definition of “detention facility” was inserted, excluding places used to hold people “on a short-term, transitory basis.” Problem solved — and no messy public explanation damped Mr. Obama’s celebration.

“Pragmatism over ideology,” his campaign national security team had advised in a memo in March 2008. It was counsel that only reinforced the president’s instincts.

Even before he was sworn in, Mr. Obama’s advisers had warned him against taking a categorical position on what would be done with Guantánamo detainees. The deft insertion of some wiggle words in the president’s order showed that the advice was followed.

Some detainees would be transferred to prisons in other countries, or released, it said. Some would be prosecuted — if “feasible” — in criminal courts. Military commissions, which Mr. Obama had criticized, were not mentioned — and thus not ruled out.

As for those who could not be transferred or tried but were judged too dangerous for release? Their “disposition” would be handled by “lawful means, consistent with the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States and the interests of justice.”

A few sharp-eyed observers inside and outside the government understood what the public did not. Without showing his hand, Mr. Obama had preserved three major policies — rendition, military commissions and indefinite detention — that have been targets of human rights groups since the 2001 terrorist attacks.

But a year later, with Congress trying to force him to try all terrorism suspects using revamped military commissions, he deployed his legal skills differently — to preserve trials in civilian courts.

It was shortly after Dec. 25, 2009, following a close call in which a Qaeda-trained operative named Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab had boarded a Detroit-bound airliner with a bomb sewn into his underwear.

Mr. Obama was taking a drubbing from Republicans over the government’s decision to read the suspect his rights, a prerequisite for bringing criminal charges against him in civilian court.

The president “seems to think that if he gives terrorists the rights of Americans, lets them lawyer up and reads them their Miranda rights, we won’t be at war,” former Vice President Dick Cheney charged.

Sensing vulnerability on both a practical and political level, the president summoned his attorney general, Eric H. Holder Jr., to the White House.

F.B.I. agents had questioned Mr. Abdulmutallab for 50 minutes and gained valuable intelligence before giving him the warning. They had relied on a 1984 case called New York v. Quarles, in which the Supreme Court ruled that statements made by a suspect in response to urgent public safety questions — the case involved the location of a gun — could be introduced into evidence even if the suspect had not been advised of the right to remain silent.

Mr. Obama, who Mr. Holder said misses the legal profession, got into a colloquy with the attorney general. How far, he asked, could Quarles be stretched? Mr. Holder felt that in terrorism cases, the court would allow indefinite questioning on a fairly broad range of subjects.

Satisfied with the edgy new interpretation, Mr. Obama gave his blessing, Mr. Holder recalled.

“Barack Obama believes in options: ‘Maintain my options,’ “ said Jeh C. Johnson, a campaign adviser and now general counsel of the Defense Department.

‘They Must All Be Militants’

That same mind-set would be brought to bear as the president intensified what would become a withering campaign to use unmanned aircraft to kill Qaeda terrorists.

Just days after taking office, the president got word that the first strike under his administration had killed a number of innocent Pakistanis. “The president was very sharp on the thing, and said, ‘I want to know how this happened,’ “ a top White House adviser recounted.

In response to his concern, the C.I.A. downsized its munitions for more pinpoint strikes. In addition, the president tightened standards, aides say: If the agency did not have a “near certainty” that a strike would result in zero civilian deaths, Mr. Obama wanted to decide personally whether to go ahead.

The president’s directive reinforced the need for caution, counterterrorism officials said, but did not significantly change the program. In part, that is because “the protection of innocent life was always a critical consideration,” said Michael V. Hayden, the last C.I.A. director under President George W. Bush.

It is also because Mr. Obama embraced a disputed method for counting civilian casualties that did little to box him in. It in effect counts all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants, according to several administration officials, unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent.

Counterterrorism officials insist this approach is one of simple logic: people in an area of known terrorist activity, or found with a top Qaeda operative, are probably up to no good. “Al Qaeda is an insular, paranoid organization — innocent neighbors don’t hitchhike rides in the back of trucks headed for the border with guns and bombs,” said one official, who requested anonymity to speak about what is still a classified program.

This counting method may partly explain the official claims of extraordinarily low collateral deaths. In a speech last year Mr. Brennan, Mr. Obama’s trusted adviser, said that not a single noncombatant had been killed in a year of strikes. And in a recent interview, a senior administration official said that the number of civilians killed in drone strikes in Pakistan under Mr. Obama was in the “single digits” — and that independent counts of scores or hundreds of civilian deaths unwittingly draw on false propaganda claims by militants.

But in interviews, three former senior intelligence officials expressed disbelief that the number could be so low. The C.I.A. accounting has so troubled some administration officials outside the agency that they have brought their concerns to the White House. One called it “guilt by association” that has led to “deceptive” estimates of civilian casualties.

“It bothers me when they say there were seven guys, so they must all be militants,” the official said. “They count the corpses and they’re not really sure who they are.”

‘A No-Brainer’

About four months into his presidency, as Republicans accused him of reckless naïveté on terrorism, Mr. Obama quickly pulled together a speech defending his policies. Standing before the Constitution at the National Archives in Washington, he mentioned Guantánamo 28 times, repeating his campaign pledge to close the prison.

But it was too late, and his defensive tone suggested that Mr. Obama knew it. Though President George W. Bush and Senator John McCain, the 2008 Republican candidate, had supported closing the Guantánamo prison, Republicans in Congress had reversed course and discovered they could use the issue to portray Mr. Obama as soft on terrorism.

Walking out of the Archives, the president turned to his national security adviser at the time, Gen. James L. Jones, and admitted that he had never devised a plan to persuade Congress to shut down the prison.

“We’re never going to make that mistake again,” Mr. Obama told the retired Marine general.

General Jones said the president and his aides had assumed that closing the prison was “a no-brainer — the United States will look good around the world.” The trouble was, he added, “nobody asked, ‘O.K., let’s assume it’s a good idea, how are you going to do this?’ “

It was not only Mr. Obama’s distaste for legislative backslapping and arm-twisting, but also part of a deeper pattern, said an administration official who has watched him closely: the president seemed to have “a sense that if he sketches a vision, it will happen — without his really having thought through the mechanism by which it will happen.”

In fact, both Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and the attorney general, Mr. Holder, had warned that the plan to close the Guantánamo prison was in peril, and they volunteered to fight for it on Capitol Hill, according to officials. But with Mr. Obama’s backing, his chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, blocked them, saying health care reform had to go first.

When the administration floated a plan to transfer from Guantánamo to Northern Virginia two Uighurs, members of a largely Muslim ethnic minority from China who are considered no threat to the United States, Virginia Republicans led by Representative Frank R. Wolf denounced the idea. The administration backed down.

That show of weakness doomed the effort to close Guantánamo, the same administration official said. “Lyndon Johnson would have steamrolled the guy,” he said. “That’s not what happened. It’s like a boxing match where a cut opens over a guy’s eye.”

The Use of Force

It is the strangest of bureaucratic rituals: Every week or so, more than 100 members of the government’s sprawling national security apparatus gather, by secure video teleconference, to pore over terrorist suspects’ biographies and recommend to the president who should be the next to die.

This secret “nominations” process is an invention of the Obama administration, a grim debating society that vets the PowerPoint slides bearing the names, aliases and life stories of suspected members of Al Qaeda’s branch in Yemen or its allies in Somalia’s Shabab militia.

The video conferences are run by the Pentagon, which oversees strikes in those countries, and participants do not hesitate to call out a challenge, pressing for the evidence behind accusations of ties to Al Qaeda.

“What’s a Qaeda facilitator?” asked one participant, illustrating the spirit of the exchanges. “If I open a gate and you drive through it, am I a facilitator?” Given the contentious discussions, it can take five or six sessions for a name to be approved, and names go off the list if a suspect no longer appears to pose an imminent threat, the official said. A parallel, more cloistered selection process at the C.I.A. focuses largely on Pakistan, where that agency conducts strikes.

The nominations go to the White House, where by his own insistence and guided by Mr. Brennan, Mr. Obama must approve any name. He signs off on every strike in Yemen and Somalia and also on the more complex and risky strikes in Pakistan — about a third of the total.

Aides say Mr. Obama has several reasons for becoming so immersed in lethal counterterrorism operations. A student of writings on war by Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, he believes that he should take moral responsibility for such actions. And he knows that bad strikes can tarnish America’s image and derail diplomacy.

“He realizes this isn’t science, this is judgments made off of, most of the time, human intelligence,” said Mr. Daley, the former chief of staff. “The president accepts as a fact that a certain amount of screw-ups are going to happen, and to him, that calls for a more judicious process.”

But the control he exercises also appears to reflect Mr. Obama’s striking self-confidence: he believes, according to several people who have worked closely with him, that his own judgment should be brought to bear on strikes.

Asked what surprised him most about Mr. Obama, Mr. Donilon, the national security adviser, answered immediately: “He’s a president who is quite comfortable with the use of force on behalf of the United States.”

In fact, in a 2007 campaign speech in which he vowed to pull the United States out of Iraq and refocus on Al Qaeda, Mr. Obama had trumpeted his plan to go after terrorist bases in Pakistan — even if Pakistani leaders objected. His rivals at the time, including Mitt Romney, Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Mrs. Clinton, had all pounced on what they considered a greenhorn’s campaign bluster. (Mr. Romney said Mr. Obama had become “Dr. Strangelove.”)

In office, however, Mr. Obama has done exactly what he had promised, coming quickly to rely on the judgment of Mr. Brennan.

Mr. Brennan, a son of Irish immigrants, is a grizzled 25-year veteran of the C.I.A. whose work as a top agency official during the brutal interrogations of the Bush administration made him a target of fierce criticism from the left. He had been forced, under fire, to withdraw his name from consideration to lead the C.I.A. under Mr. Obama, becoming counterterrorism chief instead.

Some critics of the drone strategy still vilify Mr. Brennan, suggesting that he is the C.I.A.’s agent in the White House, steering Mr. Obama to a targeted killing strategy. But in office, Mr. Brennan has surprised many former detractors by speaking forcefully for closing Guantánamo and respecting civil liberties.

Harold H. Koh, for instance, as dean of Yale Law School was a leading liberal critic of the Bush administration’s counterterrorism policies. But since becoming the State Department’s top lawyer, Mr. Koh said, he has found in Mr. Brennan a principled ally.

“If John Brennan is the last guy in the room with the president, I’m comfortable, because Brennan is a person of genuine moral rectitude,” Mr. Koh said. “It’s as though you had a priest with extremely strong moral values who was suddenly charged with leading a war.”

The president values Mr. Brennan’s experience in assessing intelligence, from his own agency or others, and for the sobriety with which he approaches lethal operations, other aides say.

“The purpose of these actions is to mitigate threats to U.S. persons’ lives,” Mr. Brennan said in an interview. “It is the option of last recourse. So the president, and I think all of us here, don’t like the fact that people have to die. And so he wants to make sure that we go through a rigorous checklist: The infeasibility of capture, the certainty of the intelligence base, the imminence of the threat, all of these things.”

Yet the administration’s very success at killing terrorism suspects has been shadowed by a suspicion: that Mr. Obama has avoided the complications of detention by deciding, in effect, to take no prisoners alive. While scores of suspects have been killed under Mr. Obama, only one has been taken into American custody, and the president has balked at adding new prisoners to Guantánamo.

“Their policy is to take out high-value targets, versus capturing high-value targets,” said Senator Saxby Chambliss of Georgia, the top Republican on the intelligence committee. “They are not going to advertise that, but that’s what they are doing.”

Mr. Obama’s aides deny such a policy, arguing that capture is often impossible in the rugged tribal areas of Pakistan and Yemen and that many terrorist suspects are in foreign prisons because of American tips. Still, senior officials at the Justice Department and the Pentagon acknowledge that they worry about the public perception.

“We have to be vigilant to avoid a no-quarter, or take-no-prisoners policy,” said Mr. Johnson, the Pentagon’s chief lawyer.

Trade-Offs

The care that Mr. Obama and his counterterrorism chief take in choosing targets, and their reliance on a precision weapon, the drone, reflect his pledge at the outset of his presidency to reject what he called the Bush administration’s “false choice between our safety and our ideals.”

But he has found that war is a messy business, and his actions show that pursuing an enemy unbound by rules has required moral, legal and practical trade-offs that his speeches did not envision.

One early test involved Baitullah Mehsud, the leader of the Pakistani Taliban. The case was problematic on two fronts, according to interviews with both administration and Pakistani sources.

The C.I.A. worried that Mr. Mehsud, whose group then mainly targeted the Pakistan government, did not meet the Obama administration’s criteria for targeted killing: he was not an imminent threat to the United States. But Pakistani officials wanted him dead, and the American drone program rested on their tacit approval. The issue was resolved after the president and his advisers found that he represented a threat, if not to the homeland, to American personnel in Pakistan.

Then, in August 2009, the C.I.A. director, Leon E. Panetta, told Mr. Brennan that the agency had Mr. Mehsud in its sights. But taking out the Pakistani Taliban leader, Mr. Panetta warned, did not meet Mr. Obama’s standard of “near certainty” of no innocents being killed. In fact, a strike would certainly result in such deaths: he was with his wife at his in-laws’ home.

“Many times,” General Jones said, in similar circumstances, “at the 11th hour we waved off a mission simply because the target had people around them and we were able to loiter on station until they didn’t.”

But not this time. Mr. Obama, through Mr. Brennan, told the C.I.A. to take the shot, and Mr. Mehsud was killed, along with his wife and, by some reports, other family members as well, said a senior intelligence official.

The attempted bombing of an airliner a few months later, on Dec. 25, stiffened the president’s resolve, aides say. It was the culmination of a series of plots, including the killing of 13 people at Fort Hood, Tex. by an Army psychiatrist who had embraced radical Islam.

Mr. Obama is a good poker player, but he has a tell when he is angry. His questions become rapid-fire, said his attorney general, Mr. Holder. “He’ll inject the phrase, ‘I just want to make sure you understand that.’ “ And it was clear to everyone, Mr. Holder said, that he was simmering about how a 23-year-old bomber had penetrated billions of dollars worth of American security measures.

When a few officials tentatively offered a defense, noting that the attack had failed because the terrorists were forced to rely on a novice bomber and an untested formula because of stepped-up airport security, Mr. Obama cut them short.

“Well, he could have gotten it right and we’d all be sitting here with an airplane that blew up and killed over a hundred people,” he said, according to a participant. He asked them to use the close call to imagine in detail the consequences if the bomb had detonated. In characteristic fashion, he went around the room, asking each official to explain what had gone wrong and what needed to be done about it.

“After that, as president, it seemed like he felt in his gut the threat to the United States,” said Michael E. Leiter, then director of the National Counterterrorism Center. “Even John Brennan, someone who was already a hardened veteran of counterterrorism, tightened the straps on his rucksack after that.”

David Axelrod, the president’s closest political adviser, began showing up at the “Terror Tuesday” meetings, his unspeaking presence a visible reminder of what everyone understood: a successful attack would overwhelm the president’s other aspirations and achievements.

In the most dramatic possible way, the Fort Hood shootings in November and the attempted Christmas Day bombing had shown the new danger from Yemen. Mr. Obama, who had rejected the Bush-era concept of a global war on terrorism and had promised to narrow the American focus to Al Qaeda’s core, suddenly found himself directing strikes in another complicated Muslim country.

The very first strike under his watch in Yemen, on Dec. 17, 2009, offered a stark example of the difficulties of operating in what General Jones described as an “embryonic theater that we weren’t really familiar with.”

It killed not only its intended target, but also two neighboring families, and left behind a trail of cluster bombs that subsequently killed more innocents. It was hardly the kind of precise operation that Mr. Obama favored. Videos of children’s bodies and angry tribesmen holding up American missile parts flooded You Tube, fueling a ferocious backlash that Yemeni officials said bolstered Al Qaeda.

The sloppy strike shook Mr. Obama and Mr. Brennan, officials said, and once again they tried to impose some discipline.

In Pakistan, Mr. Obama had approved not only “personality” strikes aimed at named, high-value terrorists, but “signature” strikes that targeted training camps and suspicious compounds in areas controlled by militants.

But some State Department officials have complained to the White House that the criteria used by the C.I.A. for identifying a terrorist “signature” were too lax. The joke was that when the C.I.A. sees “three guys doing jumping jacks,” the agency thinks it is a terrorist training camp, said one senior official. Men loading a truck with fertilizer could be bombmakers — but they might also be farmers, skeptics argued.

Now, in the wake of the bad first strike in Yemen, Mr. Obama overruled military and intelligence commanders who were pushing to use signature strikes there as well.

“We are not going to war with Yemen,” he admonished in one meeting, according to participants.

His guidance was formalized in a memo by General Jones, who called it a “governor, if you will, on the throttle,” intended to remind everyone that “one should not assume that it’s just O.K. to do these things because we spot a bad guy somewhere in the world.”

Mr. Obama had drawn a line. But within two years, he stepped across it. Signature strikes in Pakistan were killing a large number of terrorist suspects, even when C.I.A. analysts were not certain beforehand of their presence. And in Yemen, roiled by the Arab Spring unrest, the Qaeda affiliate was seizing territory.

Today, the Defense Department can target suspects in Yemen whose names they do not know. Officials say the criteria are tighter than those for signature strikes, requiring evidence of a threat to the United States, and they have even given them a new name — TADS, for Terrorist Attack Disruption Strikes. But the details are a closely guarded secret — part of a pattern for a president who came into office promising transparency.

The Ultimate Test

On that front, perhaps no case would test Mr. Obama’s principles as starkly as that of Anwar al-Awlaki, an American-born cleric and Qaeda propagandist hiding in Yemen, who had recently risen to prominence and had taunted the president by name in some of his online screeds.

The president “was very interested in obviously trying to understand how a guy like Awlaki developed,” said General Jones. The cleric’s fiery sermons had helped inspire a dozen plots, including the shootings at Fort Hood. Then he had gone “operational,” plotting with Mr. Abdulmutallab and coaching him to ignite his explosives only after the airliner was over the United States.

That record, and Mr. Awlaki’s calls for more attacks, presented Mr. Obama with an urgent question: Could he order the targeted killing of an American citizen, in a country with which the United States was not at war, in secret and without the benefit of a trial?

The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel prepared a lengthy memo justifying that extraordinary step, asserting that while the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of due process applied, it could be satisfied by internal deliberations in the executive branch.

Mr. Obama gave his approval, and Mr. Awlaki was killed in September 2011, along with a fellow propagandist, Samir Khan, an American citizen who was not on the target list but was traveling with him.

If the president had qualms about this momentous step, aides said he did not share them. Mr. Obama focused instead on the weight of the evidence showing that the cleric had joined the enemy and was plotting more terrorist attacks.

“This is an easy one,” Mr. Daley recalled him saying, though the president warned that in future cases, the evidence might well not be so clear.

In the wake of Mr. Awlaki’s death, some administration officials, including the attorney general, argued that the Justice Department’s legal memo should be made public. In 2009, after all, Mr. Obama had released Bush administration legal opinions on interrogation over the vociferous objections of six former C.I.A. directors.

This time, contemplating his own secrets, he chose to keep the Awlaki opinion secret.

“Once it’s your pop stand, you look at things a little differently,” said Mr. Rizzo, the C.I.A.’s former general counsel.

Mr. Hayden, the former C.I.A. director and now an adviser to Mr. Obama’s Republican challenger, Mr. Romney, commended the president’s aggressive counterterrorism record, which he said had a “Nixon to China” quality. But, he said, “secrecy has its costs” and Mr. Obama should open the strike strategy up to public scrutiny.

“This program rests on the personal legitimacy of the president, and that’s not sustainable,” Mr. Hayden said. “I have lived the life of someone taking action on the basis of secret O.L.C. memos, and it ain’t a good life. Democracies do not make war on the basis of legal memos locked in a D.O.J. safe.”

Tactics Over Strategy

In his June 2009 speech in Cairo, aimed at resetting relations with the Muslim world, Mr. Obama had spoken eloquently of his childhood years in Indonesia, hearing the call to prayer “at the break of dawn and the fall of dusk.”

“The United States is not — and never will be — at war with Islam,” he declared.

But in the months that followed, some officials felt the urgency of counterterrorism strikes was crowding out consideration of a broader strategy against radicalization. Though Mrs. Clinton strongly supported the strikes, she complained to colleagues about the drones-only approach at Situation Room meetings, in which discussion would focus exclusively on the pros, cons and timing of particular strikes.

At their weekly lunch, Mrs. Clinton told the president she thought there should be more attention paid to the root causes of radicalization, and Mr. Obama agreed. But it was September 2011 before he issued an executive order setting up a sophisticated, interagency war room at the State Department to counter the jihadi narrative on an hour-by-hour basis, posting messages and video online and providing talking points to embassies.

Mr. Obama was heartened, aides say, by a letter discovered in the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan. It complained that the American president had undermined Al Qaeda’s support by repeatedly declaring that the United States was at war not with Islam, but with the terrorist network. “We must be doing a good job,” Mr. Obama told his secretary of state.

Moreover, Mr. Obama’s record has not drawn anything like the sweeping criticism from allies that his predecessor faced. John B. Bellinger III, a top national security lawyer under the Bush administration, said that was because Mr. Obama’s liberal reputation and “softer packaging” have protected him. “After the global outrage over Guantánamo, it’s remarkable that the rest of the world has looked the other way while the Obama administration has conducted hundreds of drone strikes in several different countries, including killing at least some civilians,” said Mr. Bellinger, who supports the strikes.

By withdrawing from Iraq and preparing to withdraw from Afghanistan, Mr. Obama has refocused the fight on Al Qaeda and hugely reduced the death toll both of American soldiers and Muslim civilians. But in moments of reflection, Mr. Obama may have reason to wonder about unfinished business and unintended consequences.

His focus on strikes has made it impossible to forge, for now, the new relationship with the Muslim world that he had envisioned. Both Pakistan and Yemen are arguably less stable and more hostile to the United States than when Mr. Obama became president.

Justly or not, drones have become a provocative symbol of American power, running roughshod over national sovereignty and killing innocents. With China and Russia watching, the United States has set an international precedent for sending drones over borders to kill enemies.

Mr. Blair, the former director of national intelligence, said the strike campaign was dangerously seductive. “It is the politically advantageous thing to do — low cost, no U.S. casualties, gives the appearance of toughness,” he said. “It plays well domestically, and it is unpopular only in other countries. Any damage it does to the national interest only shows up over the long term.”

But Mr. Blair’s dissent puts him in a small minority of security experts. Mr. Obama’s record has eroded the political perception that Democrats are weak on national security. No one would have imagined four years ago that his counterterrorism policies would come under far more fierce attack from the American Civil Liberties Union than from Mr. Romney.

Aides say that Mr. Obama’s choices, though, are not surprising. The president’s reliance on strikes, said Mr. Leiter, the former head of the National Counterterrorism Center, “is far from a lurid fascination with covert action and special forces. It’s much more practical. He’s the president. He faces a post-Abdulmutallab situation, where he’s being told people might attack the United States tomorrow.”

“You can pass a lot of laws,” Mr. Leiter said, “Those laws are not going to get Bin Laden dead.”

Obama’s Drone Wars strain the liberal principles he espoused in 2008

Clara Cullen

The Independent

8 June 2012

The recent New York Times article on Obama’s use of drones has reverberated across the internet. The fractured lives and fractured diplomacy these attacks have left in their wake has become the subject of articles, blogs and television segments. While drone warfare is nothing new, the article revealed that the technology has become increasingly advanced and drones are now the go-to weapon for Obama’s ‘War on Terror’. Indeed, this lurch towards more hawkish right-wing policiess has some suggesting that the President has become “George W. Bush on steroids”. I believe Obama’s drone strategy is a betrayal of all who supported him. In turn, the silence of all those who voted for “hope” and “change” is worrying; it suggests that the US liberal electorate would rather support Obama, who they perceive as a lesser political evil than his Republican adversaries, than actually questioning the political hypocrisy his foreign policy entails.

The New York Times’ article is disturbing because it explains how Obama has instituted a command structure in which he authorises each drone strike. The now infamous ‘Kill list’ demonstrates Obama’s dramatic political shift. Indeed, he has adopted policies that, as Jack Goldsmith (Bush’s Assistant Attorney General) highlighted in 2009, have “copied most of the Bush programme” and have even “expanded some of it”.

It is understandable that some are finding it hard to reconcile this ‘Call of Duty’ strategy with the poetic election campaigner of 2008. Prior to being elected, Obama was consistently wary of how the ‘War on Terror’ was being conducted. He notably proclaimed in a 2002 speech : “What I am opposed to is a dumb war. What I am opposed to is a rash war”. And though he did take cover by stating that he does not oppose all forms of war, arguably engaging in drone warfare is “dumb” and “rash”.

The fallout from Obama’s warfaring is especially embarrassing in the light of his Nobel Peace Prize award in 2009 for his “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and co-operation between peoples”. By awarding the honour to Obama, more on the basis of his anticipated achievements than actual evidence, an uncomfortable contradiction has developed: here is a man who is noted for talking peace while becoming ever more embroiled in the brutality of war.

Obama’s use of drones is only one element in his transformation from liberal to quasi-conservative. And there are commentators who believe he has always been a pragmatist and that his political record has shown him to be less idealistic than his rhetoric suggests. But even for the less cynically inclined, Obama’s continuation and extension of neo-conservative policy should be a numbing disappointment for liberals.

No doubt, US government officials will argue that Obama is engaging in the reality of modern warfare and that drones are a safer way of executing terrorists than employing ground troops. White House Counter Terrorism advisor John Brennan stated that civilian causalities are “exceedingly rare”. Well yes, they are “exceedingly rare”, but only because the CIA’s definition of a “combatant” is so broad that it effectively means anyone killed in a drone strike, as long as they are “military-age males” can be classified as a “combatant”. Such callousness damns not only those who were enamoured by Obama’s rhetoric of “hope” and “change”, but also anyone who believes civil liberties should not be eroded out of fear of the unknown.

This military policy also inadvertently undermines the US’s relations with countries crucial to its ‘War on Terror’. Diplomacy, particularly with Pakistan, has become increasingly strained following recent attacks, while Sudarsan Raghavan in The Washington Post suggested the use of drones is actually doing more damage than good to the US’s war effort.

Will such evidence against drone warfare impact on Obama’s re-election hopes? Anti-war sentiment was a large factor in catalysing the Republican Party’s electoral demise in 2008. Will it do the same for Obama? Perhaps not; Obama’s poll ratings were highest in the days following Osama bin Laden’s assassination, possibly indicating that an aggressive foreign policy is not always unwelcome. Yet a more probable explanation lies in the transitory upsurge of US patriotism following Osama bin Laden’s death. Tellingly, Obama’s poll figures quickly trailed off suggesting the latter, and indicating that a continuation of this foreign policy may not be a fast track to electoral success.

There has been a disconcerting lack of demonstrations opposing the use of drones. A few dedicated anti-war stalwarts in the Occupy movement spoke out, but they have had scant impact on public opinion. Young progressives, who were so pivotal in getting Obama elected, so fuelled by the optimism of the 2008 election campaign and so vocal in their disapproval of Bush’s war policies have all but disappeared; their voices are silent at a time when the Obama Administration is not just continuing similar policies but actually extending them. Any debate about the morality of drone warfare has not been undertaken en masse but has remained confined to academic discussions and broadsheet column inches. However, it is clear that America’s optimism has faded, and Obama’s failure to deliver on much of his inspiring rhetoric has intensified a climate of apathy. Actor Matt Damon, summed this up on CNN’s Piers Morgan Show when he stated scathingly: “I no longer hope for audacity”.

Drone strikes symbolise Obama’s transformation from a candidate who espoused change to an Imperial president very much in the mould of his predecessor. As Penn and Teller have said, the Obama Administration is “spending money America doesn’t have, to kill people they don’t know, for reasons no one understands”. His use of drone warfare is yet another test of principle for those who ever had the audacity to hope.

Obama’s ‘kill list’ is unchecked presidential power

Katrina vanden Heuvel

The Washington Post

June 12

A stunning report in the New York Times depicted President Obama poring over the equivalent of terrorist baseball cards, deciding who on a “kill list” would be targeted for elimination by drone attack. The revelations — as well as those in Daniel Klaidman’s recent book — sparked public outrage and calls for congressional inquiry.

Yet bizarrely, the fury is targeted at the messengers, not the message. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) expressed dismay that presidential aides were leaking national security information to bolster the president’s foreign policy credentials. (Shocking? Think gambling, Casablanca). Republican and Democratic senators joined in condemning the leaks. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. — AWOL in the prosecution of rampant bank fraud — roused himself to name two prosecutors to track down the leakers.

Please. Al-Qaeda knows that U.S. drones are hunting them. The Pakistanis, Yemenis, Somalis, Afghanis and others know the U.S. is behind the drones that strike suddenly from above. The only people aided by these revelations are the American people who have an overriding right and need to know.

The problem isn’t the leaks, it’s the policy. It’s the assertion of a presidential prerogative that the administration can target for death people it decides are terrorists — even American citizens — anywhere in the world, at any time, on secret evidence with no review.

It is a policy driven largely by the new technological capacity of pilotless aircraft. Drone strikes have rapidly expanded, becoming a centerpiece of the Obama strategy. Over the last three years, the Obama administration has carried out at least 239 covert drone strikes, more than five times the 44 approved under George W. Bush.

Drones are enormously seductive and widely popular. Video games made real, they are relatively cheap, risk no U.S. casualties, claim to be exactly targeted and, according to the administration, have been lethal in eliminating al-Qaeda’s operatives. As Adm. Dennis Blair, former director of national intelligence for the Obama administration before being pushed out, notes, “It plays well domestically and it is unpopular only in other countries. Any damage it does to the national interest only shows up over the long term.”

Drones are also alarming. As a recent congressional letter of inquiry notes, “They are faceless ambassadors that cause civilian deaths . . . They can generate powerful and enduring anti-American sentiment.” The drone attacks may generate as many terrorists as they dispatch. They seduce the U.S. into literally policing the world, an intrusive presence that surely will generate hostility and retribution.

Moreover, the president’s claim offends the spirit and letter of the Constitution and shreds the global laws of war. Our founders were eager to curb the prerogative of kings to wage war and foreign adventures. That is why the Constitution gave Congress the power to declare war. Yet the president now claims the right to attack anywhere in the world in an apparently endless war against terrorism.