Nous avons fusillé, nous fusillons et nous continuerons à fusiller tant que cela sera nécessaire. Notre lutte est une lutte à mort. Ernesto Che Guevara (11 décembre 1964, en treillis militaire, Assemblée générale des Nations-Unies)

Toute notre action est un cri de guerre contre l’impérialisme et un appel vibrant à l’unité des peuples contre le grand ennemi du genre humain : les États-Unis d’Amérique du Nord. Guévara

Allumer deux, trois, plusieurs Vietnam. Guévara

La Corée du Nord est un modèle dont Cuba devrait s’inspirer. Guévara (Pyongyang, 1965)

Soyez réalistes : exigez l’impossible. Guévara

Dans une révolution, on doit triompher ou mourir. Guévara

Il faut mener la guerre jusqu’où l’ennemi la mène : chez lui, dans ses lieux d’amusement; il faut la faire totalement. (avril 1967) Guévara

In a way, 1968 began in 1967 with the murder of Che. His death meant a lot to me, and countless like me, at the time. He was a role model, albeit an impossible one for us bourgeois romantics insofar as he went and did what revolutionaries were meant to do – fought and died for his beliefs. (…) He belongs more to the romantic tradition than the revolutionary one. To endure as a romantic icon, one must not just die young, but die hopelessly. Che fulfils both criteria. When one thinks of Che as a hero, it is more in terms of Byron than Marx. (…) Che’s iconic status was assured because he failed. His story was one of defeat and isolation, and that’s why it is so seductive. Had he lived, the myth of Che would have long since died. Christopher Hitchens

Spilling blood was necessary for the cause. Within two years, he would order the death of several hundred Batista partisans at La Cabana, one of the mass killings of the Cuban Revolution. Andrew Sinclair

He had this Jack London-style attitude to revolution as one great big unending adventure, but none of the political maturity to deal with the practical realities of making the country work. He had this Castilian Spanish upper-class guilt about the working class and peasants that he never quite overcame. For all the noble impulses that drove him, and I think there were many, Che’s whole life could be read as a foredoomed attempt to leave his own class. Lawrence Osborne

One of Castro’s aides asked, “Is there an economist in the room?”, and, to everyone’s surprise, Che stuck up his hand. Because they were all in awe of him, they voted him governor of the bank. It turns out Che had misheard the question. He thought the guy had asked, “Is there a Communist in the room?” (…) Suddenly, he looked straight at me and said, “So, you are with Magnum. If I catch up with your friend Andy, I’ll cut his throat”, and he drew his finger slowly across his throat.’ Andy was Andrew St George, another Magnum photographer, who had travelled with Che in the Sierra Maestra, and then later filed reports for American intelligence. ‘Che was fired up that day’, and he was maybe a showman, but it scared the hell out of me. I knew then, this was a man who was not cut out to be a politician, he was a soldier and a killer. Rene Burri

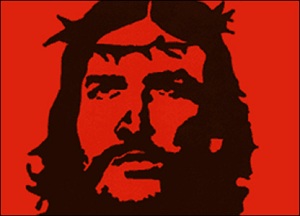

He was shot four times by a Bolivian volunteer called Mario Teran, who lives in hiding to this day.To leave the world in no doubt of his identity, his captors instructed some local nuns to wash his face, tidy his bedraggled hair and beard, then photographed his corpse. To their dismay, the image that was circulated throughout the world recalled countless Renaissance paintings of the dead Christ taken down from the cross – and so Che attained iconic status for the second time. Sean O’Hagan

Le statut d’icone historique du Che a été assuré parce qu’il a échoué. Son histoire est une histoire de défaite et d’isolement, et c’est pourquoi il est si séduisant. Aurait il vécu, et le mythe du Che serait mort depuis longtemps. Christopher Hitchens

Che was a totalitarian. He achieved nothing but disaster. Many of the early leaders of the Cuban Revolution favored a democratic-socialist direction for the new Cuba. But Che was a mainstay of the hardline pro-Soviet faction, and his faction won. Che presided over the Cuban Revolution’s first firing squads. He founded Cuba’s “labor camp” system — the system that was eventually employed to incarcerate gays, dissidents and AIDS victims. Paul Berman

Qui nous délivrera des cheguévaramanes ?

Dernier signe ostentatoire religieux autorisé dans les écoles de nos enfants, objet de culte et d’images pieuses déclinées à l’infini sous forme de T-shirts, bars, affiches, dessins, tableaux, films, hommages, chansons, poèmes, ouvrages en tous genres, tasses à café, casquettes, cartables et trousses d’école, tatouages …

Quel peut bien être ce héros et saint laïque qui a multiplié les tueries, les défaites et les échecs, fondé un système totalitaire et un goulag mais aussi détruit une économie à presque lui tout seul?

Invité à la table des plus grands (notre actuel ministre des Affaires étrangères lui dédiera même sa thèse), inspiré à des dizaines de milliers de jeunes le culte de la mort (son groupe de guerilla à Cuba était baptisé « peloton suicida »: « commando suicide ») pour plonger un continent entier dans la pire violence et causé des centaines de milliers de victimes, sans parler de ses innombrables émules jusqu’à nos actuels OLP, Hezbollah, Hamas ou al Qaeda?*

A l’heure où le monde s’apprête à fêter en grande pompe le 40e anniversaire de sa mort …

Et où un PCF bien moribond (jusqu’à la vente ou la location de ses bijoux de famille immobiliers) attend avec impatience les ventes de ses tee-shirts lors de sa Fête annuelle de l’Huma …

Petit retour, avec une critique du film « Carnets de voyage » (Walter Salles, 2004, produit par Redford) par l’excellent analyste du totalitarisme et de la violence terroriste Paul Berman, sur le dernier grand culte d’images de notre Histoire.

Et surtout, à l’instar de « ces idées chrétiennes devenues folles dont est rempli le monde moderne » (Chesterton), sur le mystère qui (dolorisme chrétien latino-américain oblige) transmuta « le petit boucher de la Cabana » en « être humain le plus complet de notre époque » (Sartre).

Autrement dit un maitre de l’échec politique et militaire ainsi que du totalitarisme en symbole universel et ultime de liberté et de justice sociale.

Pendant que les vrais dissidents et combattants de la liberté croupissent, eux, dans la prison à ciel ouvert plus connue sous le nom de Cuba …

*la seule révolution latino-américaine étant parvenue au pouvoir, les Sandinistes, n’y étant parvenue qu’en tournant le dos à la théorie guévariste du « foyer de guerilla » en s’alliant avec la bourgeoisie et l’Eglise (Gilles Bataillon)

The Cult of Che

Don’t applaud The Motorcycle Diaries.

Paul Berman

Slate

Sept. 24, 2004

The cult of Ernesto Che Guevara is an episode in the moral callousness of our time. Che was a totalitarian. He achieved nothing but disaster. Many of the early leaders of the Cuban Revolution favored a democratic or democratic-socialist direction for the new Cuba. But Che was a mainstay of the hardline pro-Soviet faction, and his faction won. Che presided over the Cuban Revolution’s first firing squads. He founded Cuba’s « labor camp » system—the system that was eventually employed to incarcerate gays, dissidents, and AIDS victims. To get himself killed, and to get a lot of other people killed, was central to Che’s imagination. In the famous essay in which he issued his ringing call for « two, three, many Vietnams, » he also spoke about martyrdom and managed to compose a number of chilling phrases: « Hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine. This is what our soldiers must become … »— and so on. He was killed in Bolivia in 1967, leading a guerrilla movement that had failed to enlist a single Bolivian peasant. And yet he succeeded in inspiring tens of thousands of middle class Latin-Americans to exit the universities and organize guerrilla insurgencies of their own. And these insurgencies likewise accomplished nothing, except to bring about the death of hundreds of thousands, and to set back the cause of Latin-American democracy—a tragedy on the hugest scale.

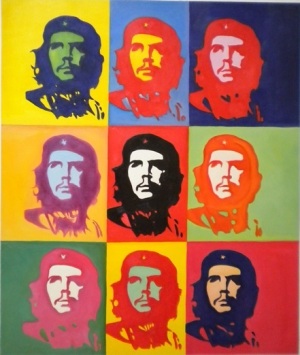

The present-day cult of Che—the T-shirts, the bars, the posters—has succeeded in obscuring this dreadful reality. And Walter Salles’ movie The Motorcycle Diaries will now take its place at the heart of this cult. It has already received a standing ovation at Robert Redford’s Sundance film festival (Redford is the executive producer of The Motorcycle Diaries) and glowing admiration in the press. Che was an enemy of freedom, and yet he has been erected into a symbol of freedom. He helped establish an unjust social system in Cuba and has been erected into a symbol of social justice. He stood for the ancient rigidities of Latin-American thought, in a Marxist-Leninist version, and he has been celebrated as a free-thinker and a rebel. And thus it is in Salles’ Motorcycle Diaries.

The film follows the young Che and his friend Alberto Granado on a vagabond tour of South America in 1951-52—which Che described in a book published under the title Motorcycle Diaries, and Granado in a book of his own. Che was a medical student in those days, and Granado a biochemist, and in real life, as in the movie, the two men spent a few weeks toiling as volunteers in a Peruvian leper colony. These weeks at the leper colony constitute the dramatic core of the movie. The colony is tyrannized by nuns, who maintain a cruel social hierarchy between the staff and the patients. The nuns refuse to feed people who fail to attend mass. Young Che, in his insistent honesty, rebels against these strictures, and his rebellion is bracing to witness. You think you are observing a noble protest against the oppressive customs and authoritarian habits of an obscurantist Catholic Church at its most reactionary.

Yet the entire movie, in its concept and tone, exudes a Christological cult of martyrdom, a cult of adoration for the spiritually superior person who is veering toward death—precisely the kind of adoration that Latin America’s Catholic Church promoted for several centuries, with miserable consequences. The rebellion against reactionary Catholicism in this movie is itself an expression of reactionary Catholicism. The traditional churches of Latin America are full of statues of gruesome bleeding saints. And the masochistic allure of those statues is precisely what you see in the movie’s many depictions of young Che coughing out his lungs from asthma and testing himself by swimming in cold water—all of which is rendered beautiful and alluring by a sensual backdrop of grays and browns and greens, and the lovely gaunt cheeks of one actor after another, and the violent Andean landscapes.

The movie in its story line sticks fairly close to Che’s diaries, with a few additions from other sources. The diaries tend to be haphazard and nonideological except for a very few passages. Che had not yet become an ideologue when he went on this trip. He reflected on the layered history of Latin America, and he expressed attitudes that managed to be pro-Indian and, at the same time, pro-conquistador. But the film is considerably more ideological, keen on expressing an « indigenist » attitude (to use the Latin-American Marxist term) of sympathy for the Indians and hostility to the conquistadors. Some Peruvian Marxist texts duly appear on the screen. I can imagine that Salles and his screenwriter, José Rivera, have been influenced more by Subcomandante Marcos and his « indigenist » rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico, than by Che.

And yet, for all the ostensible indigenism in this movie, the pathos here has very little to do with the Indian past, or even with the New World. The pathos is Spanish, in the most archaic fashion—a pathos that combines the Catholic martyrdom of the Christlike scenes with the on-the-road spirit not of Jack Kerouac (as some people may imagine) but of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, a tried-and-true formula in Spanish culture. (See Benito Pérez Galdós’ classic 19th-century novel Nazarín.) If you were to compare Salles’ The Motorcycle Diaries, with its pious tone, to the irrevent, humorous, ironic, libertarian films of Pedro Almodóvar, you could easily imagine that Salles’ film comes from the long-ago past, perhaps from the dark reactionary times of Franco—and Almodóvar’s movies come from the modern age that has rebelled against Franco.

The modern-day cult of Che blinds us not just to the past but also to the present. Right now a tremendous social struggle is taking place in Cuba. Dissident liberals have demanded fundamental human rights, and the dictatorship has rounded up all but one or two of the dissident leaders and sentenced them to many years in prison. Among those imprisoned leaders is an important Cuban poet and journalist, Raúl Rivero, who is serving a 20-year sentence. In the last couple of years the dissident movement has sprung up in yet another form in Cuba, as a campaign to establish independent libraries, free of state control; and state repression has fallen on this campaign, too.

These Cuban events have attracted the attention of a number of intellectuals and liberals around the world. Václav Havel has organized a campaign of solidarity with the Cuban dissidents and, together with Elena Bonner and other heroic liberals from the old Soviet bloc, has rushed to support the Cuban librarians. A group of American librarians has extended its solidarity to its Cuban colleagues, but, in order to do so, the American librarians have had to put up a fight within their own librarians’ organization, where the Castro dictatorship still has a number of sympathizers. And yet none of this has aroused much attention in the United States, apart from a newspaper column or two by Nat Hentoff and perhaps a few other journalists, and an occasional letter to the editor. The statements and manifestos that Havel has signed have been published in Le Monde in Paris, and in Letras Libres magazine in Mexico, but have remained practically invisible in the United States. The days when American intellectuals rallied in any significant way to the cause of liberal dissidents in other countries, the days when Havel’s statements were regarded by Americans as important calls for intellectual responsibility—those days appear to be over.

I wonder if people who stand up to cheer a hagiography of Che Guevara, as the Sundance audience did, will ever give a damn about the oppressed people of Cuba—will ever lift a finger on behalf of the Cuban liberals and dissidents. It’s easy in the world of film to make a movie about Che, but who among that cheering audience is going to make a movie about Raúl Rivero?

As a protest against the ovation at Sundance, I would like to append one of Rivero’s poems to my comment here. The police confiscated Rivero’s books and papers at the time of his arrest, but the poet’s wife, Blanca Reyes, was able to rescue the manuscript of a poem describing an earlier police raid on his home. Letras Libres published the poem in Mexico. I hope that Rivero will forgive me for my translation. I like this poem because it shows that the modern, Almodóvar-like qualities of impudence, wit, irreverence, irony, playfulness, and freedom, so badly missing from Salles’ pious work of cinematic genuflection, are fully alive in Latin America, and can be found right now in a Cuban prison.

Paul Berman is the author of Terror and Liberalism and The Passion of Joschka Fisch

Voir aussi la très complète critique de l’Observer (basée notamment sur des entretiens avec le journaliste anglo-américain Christopher Hitchens et les historiens anglais Andrew Sinclair et Lawrence Osborne ainsi qu’avec le photographe Rene Burri).

For 40 years he has been a sex symbol, heroic victim and the ultimate poster boy of revolutionary chic. But behind the myth of Che Guevara lie darker truths. On the eve of a new film, it is time to reassess the Sixties’ most enduring icon

Sean O’Hagan

July 11, 2004

The Observer

On the outskirts of Vallegrande, a mountain village in Bolivia, there is a single airstrip, little more than a long ribbon of rubble and dirt. It was there, seven years ago, that a team of forensic scientists from Argentina and Cuba began digging in search of the skeleton of a man with no hands. They found it after a few days, buried alongside the bones of six others.

Thirty years after his death, the remains of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, whose hands had been cut off following his execution by his Bolivian army captors, were finally returned to Cuba, the homeland he adopted and helped remake in his image. His final resting place is a mausoleum in the suburbs of the city of Santa Clara, a site of almost religious significance to Cubans who lived though the revolution of 1959. Vallegrande, where his corpse was put on public display following his execution, remains much as it was, a forlorn place with little trace of his presence save for the hawkers of cheap Che memorabilia who wait for the tourist buses. On the wall of the town’s public telephone office, someone has written, ‘Che – alive as they never wanted you to be’.

In the tumultuous year that followed Guevara’s death, that sentiment was echoed in the slogan ‘Che lives!’ which appeared on walls in Paris, Prague, Berkeley and Belfast. During the political unrest of 1968, it became a clarion call for what seemed like a spontaneous global insurrection and, for a brief moment, it seemed like the old order – capitalism, the Cold War, conservatism, militarism – might actually be replaced by something (though what exactly was never defined) younger and freer. That something was symbolised by the doomed romantic figure of Che Guevara, whose short life ended in a kind of martyrdom in the mountains of Bolivia, where the CIA openly admitted their role in his capture.

‘In a way, 1968 began in 1967 with the murder of Che,’ says the author and political journalist, Christopher Hitchens, who describes himself as ‘a recovering Marxist, not ashamed, not unbowed, but thoughtful’. Like many who came of age politically in the late Sixties, Hitchens was in thrall to the personality cult that attended Che. ‘His death meant a lot to me, and countless like me, at the time. He was a role model, albeit an impossible one for us bourgeois romantics insofar as he went and did what revolutionaries were meant to do – fought and died for his beliefs.’

Almost 40 years on, the wave of romantic revolutionary idealism Che helped ignite seems as unreal as Alice’s wonderland, and the Communist ideology that inspired it dated and anachronistic. Che’s defiant image may still hang in the offices of Andy Gilchrist, leader of the Fire Brigades’ Union, and Bob Crow of the Rail, Maritime and Transport Union but, politically at least, it is a relic of a bygone era, as arcane in its way as as those old ornate union banners. Internationally, too, Guevara’s ideological legacy is in tatters, his memory kept alive only by the few remaining leftist guerrilla movements such as the Zapatistas in Mexico, or the recently established People’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, whose guerrilla leader Che trained back in the Sixties.

In Cuba, Guevara remains a quasi- saintly figure, as well as a symbol of what was, and what might have been, in Castro’s now faltering state. Though it has survived decades of sanctions and attempts to assassinate its leader, the socialist republic of Cuba is now under threat from within: sex tourism and Castro’s treatment of dissidents and gays have long since sullied the idea of equality that underpinned the revolution of 1959. And yet, the myth of Che endures.

That myth has long since floated free of Cuba and its revolution, becoming an amorphous entity that has little to do with Guevara’s politics or the historical context that produced him. In 1967, the same year that Che died, the radical French activist Guy Debord wrote The Society of the Spectacle which, among other things, predicted our current obsession with celebrity and event. ‘All that was once directly lived’, wrote Debord, ‘has become mere representation.’ Nowhere is this dictum more starkly illustrated than in the case of Che, who, in the four decades since his death, has been used to sell everything from china mugs to denim jeans, herbal tea to canned beer. There was, maybe still is, a brand of soap powder bearing his name, along with the slogan ‘Che washes whiter’. Today, Che lives! all right, but not in the way he or his fellow revolutionaries could ever have imagined in their worst nightmares. He has become a global brand.

The late Alberto Korda – whose iconic photograph of the bearded and long-haired Che wearing a beret with a red star may be the most appropriated image ever – won a moral victory of sorts when he successfully sued a British advertising agency for using it in an ad for Smirnoff vodka. The appropriation, though, is unstoppable, and radical chic was elevated to a new level of absurdity when Madonna recently dressed up as Che for the cover of her single ‘American Life’. As I write, Korda’s image is being debunked in the poster for Politics, Ricky Gervais’s stand-up show, which sees the creator of The Office sporting a beret, beard, fatigues and fake tan. Had he wanted a real one, he could have booked a holiday with ‘Che Trails’, which offers trips to Cuba where you can ‘follow in the footsteps of the famous revolutionary’.

‘Ironically, Che’s life has been emptied of the meaning he would have wanted it to have,’ asserts Jorge Castañeda, author of Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara . ‘Whatever the left might think, he has long since ceased to be an ideological and political figure.’ Castañeda insists, though, that Che still possesses ‘an extraordinary relevance. He’s a symbol of a time when people died heroically for what they believed in. People don’t do that any more.’

Hitchens, too, believes that Che endures not because of how he lived, but how he died. ‘He belongs more to the romantic tradition than the revolutionary one. To endure as a romantic icon, one must not just die young, but die hopelessly. Che fulfils both criteria. When one thinks of Che as a hero, it is more in terms of Byron than Marx.’

The myth of Che the romantic hero is about to enter a new phase with the release of The Motorcycle Diaries , a rose-tinted road movie based on the book the pre-revolutionary Ernesto Guevara wrote about his journey across Latin America in the company of his best friend, Alberto Granado. Directed by Walter Salles, who made Central Station and produced City of God, it comes trailing critical plaudits from this year’s Cannes film festival. If, as the historian Robert Conquest once claimed, the cult of Che among the young is based on ‘one of the unfortunate afflictions to which the human mind is prone… adolescent revolutionary romanticism’, Salles should have a sure-fire hit on his hands. The presence of Hollywood’s hippest heartthrob, Gael García Bernal – star of Amores Perros and Almodóvar’s Bad Education – in the lead role will ensure that an impressionable new generation will discover Che, albeit as a tousled, sun-kissed loveable rogue on a road trip to political epiphany.

‘The Che of The Motorcycle Diaries is more akin to Jack Kerouac or Neal Casady than Marx or Lenin,’ says the film’s producer, and former head of FilmFour, Paul Webster. ‘He was naturally drawn to the peripatetic lifestyle that defined the Fifties and Sixties, that sense of constant motion and adventure that began with the Beats. Walter’s film gives you a glimpse of the young, idealistic Ernesto Guevara before he became Che, the legend.’ Webster wouldn’t have been so keen to finance a film about the young Fidel Castro, then? ‘No. There is no myth around Castro. Che was young and beautiful, and that, as much as all that happened later, is what underpins the myth. Paul Newman once said, « If I’d been born with brown eyes, I wouldn’t be a film star. » Well, if Che hadn’t been born so good-looking, he wouldn’t be a mythical revolutionary.’

At least two other films about Guevara are currently in development, one directed by Steven Soderbergh, and rumoured to star Benicio del Toro, the other a vehicle for Antonio Banderas, who has already played Che in Evita. Hollywood has flirted with the notion of the romantic revolutionary before, most notably in Spike Lee’s flawed bio-pic Malcolm X and in Neil Jordan’s confused portrait of Irish Republican Michael Collins. The late Marlon Brando made a less than convincing Zapata in Viva Zapata! in 1952. More recently, Oliver Stone made a controversial hagiographic documentary about Fidel Castro. Its release was put on hold when, in April, Castro executed three Cubans who had hijacked the ferry, and sentenced 78 dissident writers to 28 years in prison.

Unlike Salles, Soderbergh will have to tackle the contradictions of Che’s revolutionary life, and show the ruthless guerrilla leader as well as the romantic pin-up. With all Hollywood’s powers of persuasion, it is difficult to see post-9/11 US audiences taking to a gun-toting Communist guerrilla fighter preaching anti-American, anti-capitalist rhetoric, and calling for ‘a dozen Vietnams’.

Hollywood’s sudden renewed interest in Che – he was lionised once before in a best-forgotten 1969 epic Che!, starring Omar Sharif opposite Jack Palance as a fiendish Fidel – backs up Hitchens’s view that while Guevara’s ideological cachet may be at an all time low, his status as both sex symbol and heroic victim is undiminished. Once dubbed ‘the poster boy for the revolution’ by the right, Che was transformed into a global pin-up at the very moment of his greatest triumph, when Korda, a fledgling fashion photographer, snapped him standing beside Castro on a balcony in Havana on 5 March 1960.

‘Finding Che in his lens,’ writes Jon Lee Anderson, in Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life , ‘Korda focused and was stunned by the expression on Che’s face. It was one of absolute implacability. He snapped and the photo soon went around the world, eventually becoming the famous poster that would adorn so many college bedrooms. In it, Che appears as the ultimate revolutionary icon, his eyes staring boldly into the future, his expression a virile embodiment of outrage at social injustice.’

The die was cast. By 1970, that defiant image had become, as the British pop artist Peter Blake later put it, ‘one of the great icons of the 20th century’, appearing on T-shirts, badges and postcards, a secular version of the holy pictures and relics of Catholic saints. The same image was silk-screened by Andy Warhol, and took its place alongside Marilyn Monroe and James Dean in the iconography of Pop Art. The transformation from symbol of violent revolution to emblem of Sixties cool was complete, and Che has remained more Lennon than Lenin ever since.

‘The image of Che was just so right for the time,’ says liberal American writer Lawrence Osborne, whose critique of Guevara appeared recently in the New York Observer. ‘Che was the revolutionary as rock star. Korda, as a fashion photographer, sensed that instinctively, and caught it. Before then, the Nazis were the only political movement to understand the power of glamour and sexual charisma, and exploit it. The Communists never got it. Then you have the Cuban revolution, and into this void come these macho guys with their straggly hair and beards and big-dick glamour, and suddenly Norman Mailer and all the radi cal chic crowd are creaming their jeans. Che had them in the palm of his hand, and he knew it. What he didn’t know, of course, was how much that image would define him.’

Osborne sees Che’s iconographic status as being maintained in part by ‘the absence of questioning voices addressing the darker side of the man and his ideology’. In Guevara’s political writing he detects a ‘puritanical zeal and pure and undisguised hatred’ that, in places, becomes almost pathological. ‘This was a guy who preached hatred, who wrote speeches that were almost proto-fascist,’ he says, quoting a speech that ends, ‘Relentless hatred of the enemy impels us over and over, and transforms us into effective and selective violent cold killing machines.’

Osborne points to the contradiction between the Che who spouted such rhetoric, and the Che who has been elevated to the level of secular saint. ‘The right got it wrong when they called him a poster boy for the revolution. Che was much more than that – he was a steely, driven, ruthless leader. He may have been an idealist, but he was also someone unafraid to get his hands dirty in pursuit of an ideal. His contradictions define him more than anything else’.

From the start, Ernesto Guevara – the nickname Che came later from his habit of referring to everyone as che, or ‘pal’ – was a magnetic and strong-willed presence. Born in 1928, to aristocratic but radical parents in Rosaria, Argentina, he was the first of five children. His character was forged in part by the chronic asthma that would dog him until his death.

‘His battle with asthma had much to do with what he became,’ says Castañeda. ‘As a child he grew used to resisting and overcoming a terrible illness through sheer will, and came to the conclusion early on that every problem could be solved or defeated through sheer will, even America, even global capitalism. That, in a way, was his strength and his downfall.’

Che’s mother, Celia, from whom he inherited his indomitable spirit, and with whom he corresponded throughout his life, inculcated in him a free spirit and a passionate hatred of the Peronist right in Argentina. With her encouragement, he studied medicine in Buenos Aires, interrupting his education to undertake the motorcycle trip that politicised him.

In The Motorcycle Diaries, he describes the exploitation and poverty he sees everywhere, which he identifies as ‘the living representation of the proletariat in any part of the world’. By the book’s end, his anger has turned to hatred. ‘I feel my nostrils dilate,’ he writes, ‘savouring the acrid smell of gunpowder and blood, of the enemy’s death.’ Youthful posturing maybe but, as his later life showed, Che had a cold-blooded streak as well as a love of battle.

In 1954, having seen the CIA-backed coup overthrow the socialist government in Guatemala, Che fled to Mexico, where he met the exiled Fidel Castro, who was plotting revolution against the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Che immediately volunteered his services as a medical officer and, while training with Castro’s guerrillas in Mexico, married his first wife, Hilda Gadea. Their daughter, Hildita, was just one year old when Che set sail for Cuba with Castro and 80 other exiles, and began the guerrilla campaign against Batista.

Initially, the campaign was a catalogue of disasters but slowly the rebels gained local support, often from peasants who realised it was more dangerous to support Batista than Che. ‘Denouncing us put them in danger,’ he wrote in his Cuban war diaries, ‘since revolutionary justice was speedy.’ In 1958, in a battle that has now entered Cuban folklore, a few hundred rebels defeated 10,000 of Batista’s men in the Sierra Maestra mountains, and Castro and Che’s impossible adventure sud denly turned into a real revolution. By the time they took Havana in 1959, Che had taken up with the woman who would become his second wife, 24-year-old Aleida March de la Torre. Politically, Aleida and Che were incompatible as she belonged to an anti-Communist revolutionary faction that he hated. But, as Jon Lee Anderson notes, ‘When it came to women, especially attractive women, Che tended to put his political philosophies on hold.’

In truth, though, the same kind of contradictions attended those politic philosophies. Che was an inspiring leader but also a harsh and unbending taskmaster, who meted out stern punishment. On his orders, several peasants were executed for disloyalty, as were local bandits who preyed on the poor. Others, often no more than boys, underwent mock executions. ‘We blindfolded them,’ he wrote later, ‘and subjected them to the anguish of a simulated firing squad.’

In his trenchant short study, Che Guevara, the British historian Andrew Sinclair concludes that, during the guerrilla war, Che ‘discovered a cold ruthlessness in his nature. Spilling blood was necessary for the cause. Within two years, he would order the death of several hundred Batista partisans at La Cabana, one of the mass killings of the Cuban Revolution.’ Later too, after the botched Bay of Pigs invasion by anti-Communist Cuban exiles, all the survivors were summarily shot.

In the halcyon post-revolution days, Che was made Governor of the National Bank, his face appearing on the two peso note. Magnum photographer Rene Burri – he took another defining photograph of Che, eyes blazing, cigar clamped in the side of his mouth – tells this story about the haphazard creation of Castro’s first cabinet. ‘One of Castro’s aides asked, « Is there an economist in the room? », and, to everyone’s surprise, Che stuck up his hand. Because they were all in awe of him, they voted him governor of the bank. It turns out Che had misheard the question. He thought the guy had asked, « Is there a Communist in the room? »‘

Che did not last long in the post, and was soon made Minister for Industry, a job that made him a nomadic ambassador for the revolution. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 Che was more bullish even than Castro or Khrushchev, seemingly unconcerned that the whole world was holding its breath over the outcome. ‘The worst thing I heard about him,’ says Hitchens, ‘is that he was in favour of launching the missiles. That, for me, is a contradiction too far. You can’t be a great revolutionary who wants to free the world and be a guy who wants to push the button. You can only be one or the other.’

Rene Burri photographed Che in Havana in 1963, just months after the Cuban missile crisis. Che was being interviewed by an American woman from Look magazine. ‘I was in his tiny office for three hours, the blinds closed throughout, and Che was pacing the room like a caged tiger. The interview was like a cockfight between Communism and capitalism, and he was strutting and angry, hectoring this woman, and chomping on his cigar. Suddenly, he looked straight at me and said, « So, you are with Magnum. If I catch up with your friend Andy, I’ll cut his throat », and he drew his finger slowly across his throat.’ Andy was Andrew St George, another Magnum photographer, who had travelled with Che in the Sierra Maestra, and then later filed reports for American intelligence. ‘Che was fired up that day’ says Burri, ‘and he was maybe a showman, but it scared the hell out of me. I knew then, this was a man who was not cut out to be a politician, he was a soldier and a killer.’

By 1965, Burri had been proven right, and Che, fed up with the difficulties of trying to make post-revolutionary Cuba work, left the island to pursue armed struggle elsewhere, convinced that he could be the catalyst for countless revolutions in Africa and Latin America.

‘There is a sense, seldom articulated, that Che, for all his heroism and romance, was a wild card, and that even Castro realised this relatively early on,’ says Lawrence Osborne. ‘He had this Jack London-style attitude to revolution as one great big unending adventure, but none of the political maturity to deal with the practical realities of making the country work. He had this Castilian Spanish upper-class guilt about the working class and peasants that he never quite overcame. For all the noble impulses that drove him, and I think there were many, Che’s whole life could be read as a foredoomed attempt to leave his own class.’

In 1965, Che’s adventurism and ideological zealotry led him him to Africa, and an unsuccessful attempt at revolution in the Congo. From there, he returned briefly to Cuba, whence, increasingly estranged from Castro, he set off for Bolivia to begin his last and final guerrilla war. Of all the books written by Guevara, The Bolivian Diaries are the most powerful and affecting, not least because the ideological demagoguery of old has disappeared, replaced by a more stoical voice. It is a diary of struggle and hardship, of dismay and defeat, the antithesis of The Motorcycle Diaries, and, of course, not a story that Hollywood will ever tell.

He was captured at the Yuro Ravine in 1967 by troops loyal to military President Barrientos. Over the phone from Mexico, Castañeda tells me that he is certain Castro had a troop of men ready to go to Bolivia as soon as he heard that Che was in danger, but that the Soviet deputy, Kosygin, just returned from conciliatory talks with US President Johnson, overruled such an action. ‘Johnson made it clear to Kosygin that the Americans would countenance no attempts to save Che.’

Could Castro have saved Che, but chose not to? ‘I don’t think it’s that simple. Real politics had intervened.But Castro always had the option to mount a rescue mission even if it was by no way assured. Put it this way: there had been a time, not long before, when he would have done it without question.’

The day after his capture, bedraggled and exhausted, Che was trussed up and taken to a thatched school house in La Higuera, where he was shot four times by a Bolivian volunteer called Mario Teran, who lives in hiding to this day. Che was 39. His last words were, ‘I know you have come to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man.’

But even his enemies knew that Che Guevara’s legend would not die with him. To leave the world in no doubt of his identity, his captors instructed some local nuns to wash his face, tidy his bedraggled hair and beard, then photographed his corpse. To their dismay, the image that was circulated throughout the world recalled countless Renaissance paintings of the dead Christ taken down from the cross – and so Che attained iconic status for the second time.

‘The Christ-like image prevailed’, wrote Jorge Castañeda in Compañero. ‘It’s as if the dead Guevara looks on his killers and forgives them, and upon the world, proclaiming that he who dies for an idea is beyond suffering.’

Of course it is this ultimate sacrifice that defines the romantic myth of Che Guevara as much as his good looks or his revolutionary life. In death, he was frozen forever, and spared the ignominy of a long decline. ‘Che’s iconic status was assured because he failed,’ says Hitchens, ‘His story was one of defeat and isolation, and that’s why it is so seductive. Had he lived, the myth of Che would have long since died.’

Jorge Castañeda agrees: ‘What he shows us is that myths are bigger than mere politics or ideology, are bigger even than the cruel drift of history.’ Che lives, then, and, as long as we do not look at his life too closely, will live on as long as we need him to, and in whatever way we want him to. For him, one suspects, that would have been the cruellest fate imaginable.

· The Motorcycle Diaries is released on 27 August.

[…] avec un postier communiste-révolutionnaire (hagiographe patenté lui aussi de l’homme de main préféré du patron de la dernière prison à ciel ouvert tropicale) et d’anciens […]

J’aimeJ’aime

[…] Apologie de l’ex-homme de main de Castro par un certain facteur de Neuilly … […]

J’aimeJ’aime

[…] l’ennemi la mène: chez lui, dans ses lieux d’amusement; il faut la faire totalement. Ernesto Guevara (avril […]

J’aimeJ’aime

Il faut pourtant se rendre à l’évidence. La belle révolution de 1959 contre la dictature de Batista, celle qui avait fait lever tant d’espérance au-delà même de l’Amérique latine, celle qui avait inspiré tant de rêve et de générosité partout dans le monde, s’est transformée en cauchemar politique : pouvoir personnel, voire familial, refus d’élections libres, censure, répression policière, enfermement des dissidents, camps de travail, peine de mort, bref, l’arsenal complet d’une dictature.Certes, nous n’ignorons rien de la responsabilité américaine, avec la prolongation d’un embargo qui asphyxie un peuple et sert de prétexte à ses dirigeants pour refuser toute ouverture politique. Nous savons combien les tentatives de déstabilisation politique ont pu, dans un passé plus ou moins lointain, donner argument au régime pour consolider coûte que coûte son pouvoir et créer un climat d’état de siège. Mais la démocratie ne peut en être le prix. Et le silence des amis de Cuba serait une forme de complicité à l’égard d’un système que nous dénoncerions partout ailleurs. Aussi faut-il, de la même manière et avec la même force, demander la levée de l’embargo américain et la tenue de véritables élections libres à Cuba. Au nom même des idéaux de la gauche et au nom de notre attachement comme de notre solidarité à l’égard de la révolution cubaine, nous devons exiger la libération de tous les prisonniers politiques et l’abolition de la censure. C’est pourquoi je veux manifester mon soutien, avec d’autres socialistes qui en ont pris l’initiative, à tous ceux qui, de l’intérieur ou en exil, luttent pacifiquement et à visage découvert pour les libertés fondamentales à Cuba. Je pense en particulier au dissident social-démocrate Vladimiro Roca, qui vient de passer quatre années en prison pour avoir publié un texte demandant un peu d’ouverture au Parti communiste cubain. Je pense aussi, bien sûr, à Oswaldo Paya, instigateur courageux d’un projet de réfé-rendum sur l’avenir des institutions cubaines. La contestation de la mondialisation libérale, la dénonciation de l’impérialisme, la solidarité à l’égard des peuples opprimés par un ordre injuste sont inséparables de la lutte pour les droits de l’homme. Le rôle des progressistes, partout, c’est de faire avancer la démocratie et de ne jamais en excuser la ‘suspension’ au nom d’intérêts supérieurs, de conditions historiques ou d’étapes de développement. Cet argument a fait tant de tort au communisme. Et il a servi d’alibi à tant de glissements, de dérives, d’abandons que nous ne pouvons l’admettre à Cuba. Nous souhaitons, de tout notre coeur, une évolution. Nous appelons ceux qui peuvent avoir encore une influence à l’exercer. Nous voulons agir en amis car nous n’oublions rien de ce qu’a incarné Cuba dans notre histoire récente et dans l’engagement d’une génération : la dignité d’un peuple, la fierté de la résistance, l’émancipation par rapport au puissant voisin. Rien ne peut excuser les dérives du régime castriste. Ni la figure emblématique de Fidel Castro, ni la persistance scandaleuse de la pression américaine, ni le symbole de la lutte pour la libération nationale. Il faut donc soutenir le peuple cubain jusqu’au bout et dire la vérité sur l’inhumanité de l’embargo comme sur le régime de Cuba. Les deux sont injustifiables. »

François Hollande (Le Nouvel obs, 2003)

J’aimeJ’aime

Le mythe cubain a effectivement existé en France: les intellectuels de gauche avaient l’impression que Cuba offrait une solution à l’épineuse équation entre le socialisme et la liberté. La fascination exercée par ce régime en France a duré jusqu’à 68 et, au-delà de la gauche, a également touché une partie de la droite. Celle-ci avait trouvé son compte en applaudissant un chef révolutionnaire, Fidel Castro qui faisait un pied de nez aux Etats-Unis, une attitude qui a toujours plu en France.

Mais l’enthousiasme a fini par retomber, notamment face au soutien de Fidel Castro envers l’invasion de la Tchécoslovaquie par les troupes soviétiques en 1968 et à la répression menée contre les intellectuels et les homosexuels cubains. Le chef révolutionnaire a également envoyé des dizaines de milliers de soldats combattre en Afrique pour soutenir des guérillas favorables au socialisme soviétique, ce qui a incité la gauche à abandonner cette idée de rapprochement du socialisme et de la liberté.

La fascination envers ce régime n’est donc plus de mise depuis un certain temps. Le rêve de révolution qui ferait changer l’Amérique latine par la lutte armée n’est désormais plus partagé par grand monde: on s’est rendu compte dans ce continent qu’un certain nombre de pays qui ont une politique un peu plus nationaliste et plus ferme vis-à-vis des compagnies pétrolières, ainsi que des réformes, ont gagné bien plus que ce qu’elles ne pouvaient espérer obtenir via une révolution armée.

La visite de François Hollande à Cuba rappelle très certainement leur jeunesse à une partie de ceux qui font l’actualité. Plus que d’enthousiasme ou de fascination, on peut parler de nostalgie.

Je parlerais de dictature totalitaire. Il ne s’agit pas simplement d’un dictateur de pays du Tiers-Monde qui s’enrichit et combat ses opposants mais d’un véritable projet totalitaire d’ordre communiste: collectivisation des biens, parti unique avec un chef unique et incontesté ainsi qu’une idéologie unique et obligatoire. Dans les années 70-80, les Cubains n’avaient pas intérêt à dévier de la ligne officielle.

Ce caractère totalitaire s’illustre particulièrement bien dans le domaine de l’éducation. Les jeunes Cubains n’ont pas été élevés de façon neutre: ils ont été formés pour être de bons révolutionnaires. Tous les matins, devant le drapeau national, ils déclaraient ainsi: «nous serons comme le Che». Dans les années 80, outre les notes en mathématiques ou en physique, une attention particulière était portée aux «performances idéologiques». Un cubain n’avait pas intérêt à manquer une seule manifestation dans la rue sous peine de voir sa carrière stagner.

Il y a donc eu la mise en place d’un système totalitaire dans lequel les opposants sont envoyés en prison ou dans des camps -créés dans les années 60, ces camps ont disparu aux débuts des années 80.

Le régime cubain est épuisé et à genoux. Il a pu survivre ces dernières années grâce aux pétrodollars du Venezuela, sans lesquels l’économie cubaine ne s’en serait probablement pas sorti. Les régimes cubains et vénézuéliens sont, en effet, très proches: ils se réclament tous deux d’un socialisme qui ne ressemblent pas au socialisme européen mais se rapproche de ce qu’était nos partis communistes il y a quelques années.

Si Raul Castro ouvre actuellement son pays, c’est qu’il sent bien que les mois du Venezuela sont comptés, à cause de la baisse des prix du pétrole et d’une absence totale de réussite économique de ce pays d’Amérique latine. Cuba a donc besoin d’investissements, en particulier occidentaux, pour se sortir de cette mauvaise passe. Cette ouverture ne signifie cependant pas que les dirigeants cubains vont lâcher le pouvoir, bien au contraire. Ils estiment en effet que s’ils parviennent à redresser la situation économique -un petit peu comme à la chinoise- ils en seront remerciés et pourront par conséquent renforcer la direction du pays par le parti communiste. Raul Castro fait ainsi un pari. Je ne pense pas qu’il se soit converti lorsqu’il est allé voir le Pape! Cette visite était un message pour les Occidentaux afin de leur montrer qu’il avait changé.

Cette situation rappelle le passage de Staline à Khrouchtchev. Celui-ci, en reniant Staline, voulait à la fois renforcer l’URSS et se rapprocher de l’Occident. D’une part l’URSS changeait -l’état était moins policier- mais de l’autre son parti communiste ne voulait nullement abandonner le pouvoir. De la même façon, Raul Castro a fait évoluer un certain de choses à Cuba ces derniers temps: il avait notamment le projet de pousser deux millions (sur treize millions d’habitants) de fonctionnaires dans le secteur privé. Et il est évident que si les Occidentaux investissent, il y aura davantage de travail dans le secteur privé. Cuba n’est d’ailleurs pas la Corée du Nord: il y a la possibilité d’avoir quelques idées sur ce qui se passe à l’extérieur, même si la presse est extrêmement limitée.

Cependant, je ne pense pas que la visite de François Hollande soit d’un grand poids. Les pays occidentaux ne peuvent taper du poing sur la table en exigeant que Cuba devienne une démocratie libérale. Ce qui semble compter c’est d’être «bien placé» au cas où Cuba, un peu à la manière de la Chine ou du Vietnam, se transforme en un état au régime fort dirigé par un parti communiste avec, dans le même temps, une plus grande liberté pour la population.

http://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/monde/2015/05/11/31002-20150511ARTFIG00374-cuba-derriere-la-fascination-de-francois-hollande-la-realite-d-une-dictature.php

J’aimeJ’aime

La tactique des autorités cubaines a changé mais la situation de la liberté d’expression à Cuba n’a pas évolué d’un iota ces dernières années.

Depuis plusieurs années, il y a une volonté d’avoir moins de prisonniers politiques dans les prisons car il y a eu une prise de conscience que la communauté internationale les acceptait de moins en moins. Il y a cinq ans, Amnesty recensait une quarantaine de prisonniers d’opinion dans les prisons cubaines. Aujourd’hui, et notamment après la libération de 53 prisonniers politiques en janvier suite à la décision des Etats-Unis et de Cuba de normaliser leurs relations, il ne reste plus qu’un prisonnier politique reconnu par Amnesty International. Il y a donc une évolution positive. Mais, en fait, au lieu d’envoyer les gens en prison pour plusieurs années, le gouvernement cubain multiplie les arrestations de courte durée, le harcèlement constant des dissidents. Au lieu d’avoir 40 prisonniers d’opinion condamnés à 25 ans de prison, on a des militants des droits de l‘Homme qui sont constamment arrêtés entre 2 heures et jusqu’à 48 heures. Au lieu d’être condamné à 25 ans, ils vont être arrêtés cinq fois par mois.

Amnesty accueille positivement la volonté de normaliser les relations avec Washington. Mais cette normalisation et ces réformes économiques en cours doivent s’accompagner de réformes civiles et politiques car le système continue d’être répressif. Les tribunaux sont aux ordres du pouvoir exécutif et législatif. C’est l’Assemblée nationale qui désigne les juges et les membres de la Haute Cour. La constitution cubaine continue de garantir la liberté d’expression à la condition qu’elle ne soit pas contre le processus révolutionnaire. Il y a donc une nécessité de faire évoluer le modèle cubain d’un point de vue des droits humains. Il y a une réussite certaine du gouvernement cubain sur certains droits économiques, sociaux et culturels, notamment le droit à la santé, à l’éducation et le droit à l’alimentation mais, pour Amnesty International, les droits humains sont indivisibles.

La difficulté des opposants cubains, c’est que la liberté d’expression n’est pas garantie dans le pays. Il n’y a pas de médias indépendants à Cuba. Tout le système médiatique est aux mains du pouvoir. Il est donc compliqué pour un opposant de diffuser ses idées. On ne peut pas savoir si les positions des dissidents ont un écho dans l’opinion publique cubaine. Ces gens-là sont extrêmement isolés et n’ont pas d’accès à des canaux de communication …

Robin Guittard (Amnesty international)

J’aimeJ’aime

Il n’y a pas pire aveugle que celui qui ne veut pas voir, et cette volonté s’enracine dans des mécanismes idéologiques et de croyance dont on n’a pas forcément tiré toutes les leçons. Le communisme s’est greffé sur le mouvement ouvrier et les luttes de libération nationale, il les a instrumentalisés et pervertis de l’intérieur. Les «fronts de libération nationale» que les partis communistes ont mis en place en Indochine ont joué le même rôle de leurre que le front uni antifasciste mis en place en Europe. Par leur tactique d’alliance avec les «forces progressistes», par les sacrifices de leurs militants aux côtés des peuples dans les luttes de libération nationale, les partis communistes ont réussi à apparaître comme les partisans de la paix et de la liberté. Une fois arrivés au pouvoir, ils ont fait disparaître leurs alliés d’hier, pratiqué la terreur et développé leur emprise totalitaire sur la société. Les régimes communistes ont pratiqué le «mensonge déconcertant» qui renverse les critères du réel et de la raison, affirme que le «noir est blanc», que l’agresseur est l’agressé, que la dictature est démocratique, produisant des effets de déstabilisation et de sidération du sens commun qui a du mal à admettre qu’il soit possible de dénier la réalité à ce point.

Jean-Pierre Le Goff (ancien mao lui aussi)

J’aimeJ’aime

DANCE AVEC LES DICTATEURS (De Mélenchon à Guetta: Hollande sort son gratin pour célébrer le geolier cubain)

C’est la première fois depuis 21 ans (François Mitterrand avait reçu Fidel Castro en mars 1995) qu’un président cubain effectue une visite officielle en France. A cette occasion, François Hollande et Raul Castro signeront plusieurs accords notamment sur la dette cubaine, la France ayant accepté d’annuler progressivement le versement des intérêts de retard accumulés depuis 30 ans par la petite île. Un cadeau à plusieurs centaines de millions de dollars bienvenu pour Cuba soumis à un embargo américain depuis plus d’un demi siècle… Et pour sceller cette amitié entre les deux pays, rien ne vaut un diner d’Etat avec son lot de «people» incarnant les relations entre les deux pays. Parmi les invités on trouve, outre Jean Luc Mélenchon, le roi des DJ… David Guetta qui préparerait un grand concert à Cuba et à qui l’on prête une liaison amoureuse avec une mannequin cubaine de 22 ans Jessica Ledon.

Pas sûr pour autant que le célèbre roi de la nuit utilise ses platines ce soir. La chanteuse Nathalie Cardone est également annoncée avec son célèbre «Hasta siempre», tube de l’année 1997 en hommage au commandant Che Guevara alors que la cantatrice Barbara Hendricks est aussi prévue. Dans le domaine culturel, les personnalités du cinéma auront également lors de ce dîner une place de choix : Virginie Efira, Christophe Barratier et le célèbre Costa Gavras, tous très actifs dans le festival du film français de la Havane, ont été invités. Tandis que le boxeur et champion du monde de boxe Jean-Marc Mormeck est censé donner un peu de punch à une soirée à laquelle participeront les ministres Laurent Fabius (Affaires étrangères), Ségolène Royal (Ecologie), Marisol Touraine (Affaires sociales) et le secrétaire d’Etat Matthias Fekl (Commerce extérieur).

http://www.leparisien.fr/politique/castro-reunit-hollande-melenchon-et-david-guetta-31-01-2016-5502403.php#xtor=AD-1481423553

http://www.france24.com/fr/20160131-france-cuba-visite-officielle-raul-castro-business-economie-diplomatie-etats-unis

J’aimeJ’aime

Danse avec les dictateurs: Après le pape et Obama, les Stones au Karl Marx theater !

And moss grows fat on a rolling stone, but that’s not how it used to be …

Don McLean

Un grand moment de l’histoire du rock.

Philippe Manoeuvre

J’aimeJ’aime

A QUAND UN HOMMAGE A POL POT ?

« Avec l’exposition « Le Che à Paris », la capitale rend hommage à une figure de la révolution devenue une icône militante et romantique. »

Anne Hidalgo

https://francais.rt.com/france/46958-hommage-pol-pot-luc-ferry-furieux-hommage-anne-hidalgo-che-guevara

J’aimeJ’aime

« Plus de 200 morts de ses mains, 1700 fusillés, 4000 internés la première année de la prise de La Havane. Hidalgo ose toutes les indignités… c’est aussi à ça qu’on la reconnaît. »

Valérie Boyer

http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2017/12/30/tueur-boucher-lexpo-en-hommage-a-che-guevara-organisee-a-la-mairie-de-paris-passe-mal_a_23320063/

J’aimeJ’aime

APRES LES FAKE NEWS LA FAKE EXHIBITION!

« Fidel Castro était une figure du XXe siècle. Il avait incarné la révolution cubaine, dans les espoirs qu’elle avait suscités puis dans les désillusions qu’elle avait provoquées. Acteur de la guerre froide, il correspondait à une époque qui s’était achevée avec l’effondrement de l’Union soviétique. Il avait su représenter pour les Cubains la fierté du rejet de la domination extérieure. »

François Hollande

Che Guevara participe aussi à la création de la police secrète du régime, la tristement célèbre Seguridad del Estado, dont l’agence d’espionnage G-2, et prend lui-même la direction des tribunaux révolutionnaires. La froide machine à tuer est mise en place par Guevara qui la contrôle personnellement et qui la fait tourner!

Il devient le principal procureur révolutionnaire, quand il ne procède pas lui-même aux exécutions. Des dizaines, puis des centaines d’hommes sont fusillés. Parmi eux, des criminels du régime de Batista, bien sûr, mais aussi de simples soldats, des déserteurs et, bientôt, d’authentiques démocrates qui ont juste le malheur de ne pas approuver le régime autoritaire mis en place par Fidel Castro. Ils sont tous accusés d’être des contre-révolutionnaires et exécutés sans procès équitable, sans défense, sans justice aucune.

Pendant ce temps, Raúl Castro, plus barbare encore, procède lui-même à des exécutions de masse de soldats capturés. Bientôt la loi est aggravée: toute action «contre-révolutionnaire» est passible de la peine de mort.

Jour après jour, et sans aucun état d’âme donc, Che Guevara est le co-fondateur d’une des plus endurantes dictatures du XXe siècle. Selon Jon Lee Anderson, au moins 550 personnes ont été exécutées dans les seuls premiers mois de 1959.

Mais Che Guevara en veut plus. Lorsque Fidel Castro suggère, face aux premières critiques internationales, de ralentir les procès et de diminuer le nombre de fusillés, Che Guevara fait connaître son désaccord. Il réclame plus de pelotons d’exécutions.

Au-delà des crimes de Guevara et du nouveau régime –qui commencent à inquiéter à l’étranger et contribuent à la rupture avec Washington–, l’autre grand échec du Che concerne l’économie. Ce qui renvoie nécessairement à la question de l’exercice du pouvoir.

Le bilan est ici, si l’on ose écrire, plus désastreux encore. Les belles idées guevaristes se sont en effet fracassées sur les réalités au ministère de l’Industrie, à la tête de la banque nationale de Cuba ou comme ministre des Finances. Le Che devient le véritable tsar de l’économie cubaine.

Guevara crée de toute pièce une industrie centralisée autour de grandes unités modernes. Le résultat est vite décevant, aux yeux même du Che, et surtout calamiteux pour les Cubains, leurs conditions et leur niveau de vie. D’abord, la production du sucre chute considérablement; ensuite l’économie cubaine est peu à peu paralysée par une bureaucratisation terrible; enfin, le système encourage inévitablement le marché noir et la corruption généralisée. Bientôt, et alors que Cuba en était l’un des principaux producteurs, il faut importer du sucre!

Au lieu de redistribution, il y a nationalisation: on crée des coopératives collectives d’État pour «mieux nourrir le pays». Le Che est plus radical encore que Fidel, toujours hésitant, souvent prêt aux compromis, sur la nécessité de collectiviser l’agriculture. En moins d’une année pourtant, la recette fait long feu: les coopératives accompagnent la forte décroissance cubaine.

C’est à peu près ce qu’il demeure aujourd’hui de l’économie de Cuba, plus de cinquante ans après, dans l’état, figé, où Guevara l’a laissée.

L’obstination sans bornes

Ce qui est étrange dans cette dérive, c’est l’obstination de Guevara, son absence d’autocritique. Dès 1962, le Che se rend compte de son échec mais, en bon dogmatique, il croit que ses idées n’ont simplement pas été appliquées et respectées dans leur pureté. Au lieu d’adapter l’économie aux circonstances, d’expérimenter avant d’approfondir, de prendre acte des expériences décevantes, il persiste et signe. C’est cette obstination, déconnectée des réalités, qui a condamné le régime castriste.

On connaît la suite: peu à peu, l’économie cubaine s’effondre, le peuple est oublié, comme l’attestent encore aujourd’hui l’état calamiteux des transports publics cubains, les pénuries alimentaires, le rationnement et, même, l’échec maintenant avéré du système de santé et du modèle éducatif –en dépit de statistiques éhontément falsifiées.

Il y a plus: comme en URSS, une nouvelle classe apparaît, faite d’apparatchiks et de profiteurs castristes, les seuls à avoir accès aux produits de consommation courante et à bénéficier de la révolution.

Dans sa biographie, Jon Lee Anderson décrit maintenant un Che Guevara méconnaissable. Borné, sectaire, le communiste n’écoute plus aucun de ses conseillers, qui, parfois, tirent pourtant la sonnette d’alarme économique.

Les biographies de Jon Lee Anderson, nourries des archives de la CIA et du KGB, et dans une moindre mesure celle de Pierre Kalfon, dissipent nos derniers doutes. Dès l’origine, Che Guevara fut plus communiste que Fidel Castro, il a été très tôt fasciné par Staline et il fut pro-soviétique, avant même que Fidel ne fasse ouvertement le choix du camp socialiste (vers janvier 1960). À Cuba, Che est l’homme de la ligne dure, sans concession, le stalinien, quand Fidel est roublard, menteur, et d’abord castriste. Le Che n’est ni un guevariste, ni un communiste «soft», c’est un dogmatique «hard».

C’est donc aussi un intellectuel. On peut tout reprocher au Che sauf de n’avoir pas toujours agi au nom et pour des idées. C’est sa force, dans le grand procès de l’histoire, par rapport à un Staline, à un Mao, ou aux Castro –des intellectuels qui ne pensaient pas. Che, lui, tombera toujours du côté des idées. On garde d’ailleurs de lui l’image d’un homme avec un livre à la main et dont les sacs de voyage étaient plus lourds que ceux de ses compagnons, du fait des livres qu’il transportait. Che a constamment intellectualisé son action et pensé son combat, même s’il l’a fait dans un cadre étroit dont il n’est jamais sorti, celui d’un marxisme orthodoxe, quasi léniniste et bientôt maoïste.

En fait, Guevara est un orthodoxe qui revient à la pureté léniniste originale lorsqu’il s’éloigne des Soviétiques. Il critique l’URSS sur sa gauche! Et devient potentiellement maoiste! Le «guevarisme» a plu à travers le monde dans les années 1960 parce qu’il est apparu comme un anti-stalinisme, alors qu’il était en fait un néo-léninisme.

Le rebelle, l’iconoclaste, le franc-tireur ont fait florès –alors que l’homme était droit dans ses bottes. Lorsque Fidel obtempère, diffère, Che Guevara menace de démissionner si on n’érige pas la société socialiste tout de suite. Et si on ne crée pas l’«homme nouveau» qu’il appelle de ses vœux.

Je ne sais pas si Ernesto Guevara a lu Nietzsche et son biographe Jon Lee Anderson est silencieux sur ce point. En revanche, il révèle que le Che trouve ses premières citations de Marx… dans le Mein Kampf d’Hitler. Plus tard, Guevara développera ses idées sur l’«homme nouveau» dans ses carnets et ses discours.

«Un nouveau type d’homme doit être créé», affirme-t-il dans un discours de 1960, devant les étudiants communistes cubains. Ce qui est sûr, c’est que le Che a voulu construire une «société de guérilla», faisant du combattant téméraire de la Sierra Maestra la matrice de régénération de l’espèce humaine. Son modèle, à partir de 1960, c’est la révolution culturelle chinoise, non plus l’URSS. Il est fasciné par le Grand bond en avant de Mao et la collectivisation forcée.

Après avoir multiplié les assassinats politiques sur l’île, anéanti l’économie cubaine et contribué méthodiquement à la construction de la dictature castriste, Che Guevara se découvre au début des années 1960 une nouvelle mission: celle d’exporter et d’internationaliser la révolution cubaine. Une autre page sombre du guevarisme s’ouvre.

Dès lors, la vie du Che devient une géographie de l’extrême gauche en mouvement en Amérique latine et sa pensée va durablement nourrir toutes les dictatures d’extrême gauche, depuis les sandinistes au Nicaragua, jusqu’aux guérillas maoïstes et narcotrafiquantes FARC, au sous-commandant Marcos ou à l’autoritarisme néo-guevariste d’Hugo Chàvez au Venezuela.

Certes, Che Guevara se bat souvent contre des caudillos d’extrême gauche (au Guatemala d’abord, en Argentine ensuite, où il envoie ses hommes se faire tuer sans y aller lui-même, en Bolivie enfin). Mais à chaque fois, le Che se bat aussi contre tous les régimes «sociaux-démocrates» d’Amérique latine, contre tous les modérés, traités avec un mépris et une condescendance affligeantes (Che aurait été l’ennemi du Brésil de Lula, de l’Argentine de Cristina Kirchner comme du Chili de Michelle Bachelet).

Sur ce guevarisme mondialisé, Jon Lee Anderson apporte des informations aussi nouvelles que précieuses quant aux liens entre Che Guevara et le FLN algérien (il forme ou entraîne à Cuba des soldats et aide militairement les militants qui multiplient les opérations visant à tuer des Français en 1962). On apprend aussi les liens précoces entre le Che et les mouvements de libération nationale palestiniens (il visite dès 1959 la bande de Gaza, alors sous contrôle égyptien, et est acclamé par la foule). Bientôt, Che Guevara dénoncera le sionisme comme «réactionnaire» (anticipant même sur l’URSS qui défendra plus tard l’OLP de Yasser Arafat). Il finance et organise de très nombreuses guérillas d’extrême gauche en Amérique latine, puis en Afrique, mais sans jamais connaître un véritable succès.

Il y a plus. Che Guevara s’est mis à théoriser le «terrorisme». Dans ses écrits, ses lettres, et à travers des témoignages, on découvre un homme qui fait du sabotage la base de la guérilla et du «terrorisme» –il emploie le mot– une technique parmi d’autres.

L’extrême gauche a souvent affirmé que «Che Guevara condamnait de manière explicite le terrorisme». La réalité est donc bien différente. Pour le Che, la fin, on l’a vu, justifie les moyens. La question de la violence comme arme politique, dans la pensée du Che, ne peut pas être passée sous silence: elle est centrale. Le terrorisme, «technique» qui, à cette époque, n’a pas encore connu les développements contemporains que l’on sait, peut être choisi parmi les armes offertes dans le petit manuel du parfait guevariste. Le terrorisme est pensé, anticipé, théorisé au point où l’on peut affirmer que Che Guevara est l’un des parrains du terrorisme moderne.

Alors: faut-il rendre hommage à Che Guevara? Certains l’ont fait, comme François Hollande lors de sa visite à Cuba en 2015 ou Anne Hidaldo en organisant récemment cette fameuse exposition.

Durant trois précédents voyages récents à Cuba, j’ai discuté avec des dizaines d’étudiants qui n’ont que deux rêves aujourd’hui dans leur vie. Le premier consiste à fuir le pays pour rejoindre les États-Unis: des milliers de Cubains, opprimés par La Havane, sont prêts à mourir chaque année pour échapper à la dictature castriste et rejoindre Key West –un démenti cinglant à l’anti-américanisme du Che et à toute son idéologie. Le second est plus simple encore: il s’agit tout bêtement de déboulonner les statues de Castro et d’effacer les portraits de Che Guevara en jetant aux orties leurs beaux slogans de dictateurs. C’est ce qui va bien finir par arriver.

Ce jour-là, lorsque les jeunes cubains qui sont restés emprisonnés sur l’île, faute de pouvoir émigrer, brûleront les portraits de Che Guevara et le dénonceront comme un simple «hijo de puta», toute la jeunesse aisée occidentale, tous les touristes qui portent ample les tee-shirts du Che, comprendront leur erreur. Ceux qui le commémorent aujourd’hui aussi.

http://www.slate.fr/story/155873/exposition-paris-hommage-che-guevara-anne-hidalgo

J’aimeJ’aime

That is really attention-grabbing, You’re an overly

skilled blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and look forward to

in quest of more of your magnificent post.

Also, I have shared your site in my social networks

J’aimeJ’aime