Of course, fairy-stories are not the only means of recovery, or prophylactic against loss. Humility is enough. And there is (especially for the humble) Mooreeffoc, or Chestertonian Fantasy. Mooreeffoc is a fantastic word, but it could be seen written up in every town in this land. It is Coffee-room, viewed from the inside through a glass door, as it was seen by Dickens on a dark London day; and it was used by Chesterton to denote the queerness of things that have become trite, when they are seen suddenly from a new angle. That kind of “fantasy” most people would allow to be wholesome enough; and it can never lack for material. But it has, I think, only a limited power; for the reason that recovery of freshness of vision is its only virtue. The word Mooreeffoc may cause you suddenly to realize that England is an utterly alien land, lost either in some remote past age glimpsed by history, or in some strange dim future to be reached only by a time-machine; to see the amazing oddity and interest of its inhabitants and their customs and feeding-habits; but it cannot do more than that: act as a time-telescope focused on one spot. (…) I would venture to say that approaching the Christian story from this perspective, it has long been my feeling (a joyous feeling) that God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. …and among its marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. JRR Tolkien

Of course, fairy-stories are not the only means of recovery, or prophylactic against loss. Humility is enough. And there is (especially for the humble) Mooreeffoc, or Chestertonian Fantasy. Mooreeffoc is a fantastic word, but it could be seen written up in every town in this land. It is Coffee-room, viewed from the inside through a glass door, as it was seen by Dickens on a dark London day; and it was used by Chesterton to denote the queerness of things that have become trite, when they are seen suddenly from a new angle. That kind of “fantasy” most people would allow to be wholesome enough; and it can never lack for material. But it has, I think, only a limited power; for the reason that recovery of freshness of vision is its only virtue. The word Mooreeffoc may cause you suddenly to realize that England is an utterly alien land, lost either in some remote past age glimpsed by history, or in some strange dim future to be reached only by a time-machine; to see the amazing oddity and interest of its inhabitants and their customs and feeding-habits; but it cannot do more than that: act as a time-telescope focused on one spot. (…) I would venture to say that approaching the Christian story from this perspective, it has long been my feeling (a joyous feeling) that God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. …and among its marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. JRR Tolkien

Le monde moderne n’est pas mauvais : à certains égards, il est bien trop bon. Il est rempli de vertus féroces et gâchées. Lorsqu’un dispositif religieux est brisé (comme le fut le christianisme pendant la Réforme), ce ne sont pas seulement les vices qui sont libérés. Les vices sont en effet libérés, et ils errent de par le monde en faisant des ravages ; mais les vertus le sont aussi, et elles errent plus férocement encore en faisant des ravages plus terribles. Le monde moderne est saturé des vieilles vertus chrétiennes virant à la folie. Elles ont viré à la folie parce qu’on les a isolées les unes des autres et qu’elles errent indépendamment dans la solitude. Ainsi des scientifiques se passionnent-ils pour la vérité, et leur vérité est impitoyable. Ainsi des « humanitaires » ne se soucient-ils que de la pitié, mais leur pitié (je regrette de le dire) est souvent mensongère. G.K. Chesterton

Tous ces hommes éminents prophétisaient, avec toutes sortes d’ingéniosités différentes, ce qui allait bientôt se passer, et ils s’y prenaient au fond tous de la même manière, puisqu’ils choisissaient chacun quelque courant pour le prolonger aussi loin que le permettait l’imagination. (…) Que sera Londres d’ici cent ans? Y a-t-il quelque chose à quoi nous n’ayons pas pensé? Mettre les maisons- sens dessus dessous, plus hygiéniques, peut-être? Les hommes marchant sur leurs mains – en rendant aux pieds leur flexibilité? La lune? … Les autos? … sans tête? …. » Et c’est ainsi qu’ils déambulaient et divaguaient, puis ils mouraient et on les enterraient gentiment. Et puis on s’en alllait et les gens faisaient à leur guise. Ne cachons pas plus longtemps la pénible vérité. Le peuple avait démenti les prophètes du XXe siècle. Et au moment où le rideau se lève sur cette histoire, à quatre-vingts ans d’ici, Londres est à bien peu près ce qu’il est aujourd’hui. Chesterton

If you look back twenty years, you will find people like Ronald Knox, Cyril Alington, Chesterton himself and his many followers, talking as though such things as Socialism, Industrialism, the theory of evolution, psycho-therapy, universal compulsory education, radio, aeroplanes and what-not could be simply laughed out of existence. George Orwell

Le Napoléon de Notting Hill aurait pu s’intituler 1984. Publié en 1904, ce roman propose un tableau de Londres quatre-vingts ans plus tard. Mais au cauchemar futuriste de George Orwell, Chesterton préfère un rêve nostalgique. Pour fuir le monde moderne, ses personnages rétablissent les bonnes vieilles traditions du Moyen Age: corporations de métiers, hérauts, hallebardiers, bannières. Et puisque la féodalité redevient à la mode, le quartier de Notting Hill impose sa suzeraineté aux autres fiefs londoniens. Cette allégorie farfelue vaut surtout par les traits d’humour qui l’émaillent. L’Express

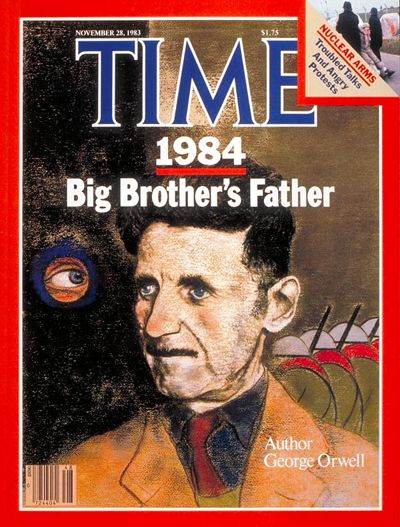

1984 était-il une réponse au défi de Chesterton?

Retour, en ce lendemain du 62e anniversaire de la publication de 1984, sur l’homme qui inspira son titre sinon son sujet au chef d’oeuvre d’Orwell …

Du moins si l’on en croit l’avocat et auteur britannique David Allen Green qui montre, contre les explications habituelles et jusqu’ici peu convaincantes d’un hypothétique renversement des deux derniers chiffres de la date de sa rédaction (1948) ou du 100e anniversaire de la Société fabienne, tant la fascination que l’hostilité d’un Orwell par ailleurs très remonté par le soutien de l’Eglise catholique au général Franco pour ce géant (dans tous les sens du terme… du haut de son 1 m 93!) qu’était alors Chesterton.

Et notammment comment, dans l’autre livre qui aurait pu lui ausssi s’intituler 1984 (Le Napoléon de Notting Hill, publié en 1904 et prétendant décrire le Londres de 80 ans plus tard) et sa fameuse préface qu’Orwell ne pouvait ne pas connaitre (Remarques préliminaires sur l’art de la prophétie), celui-ci ne se contentait pas de ridiculiser une à une, de Wells à Stead et de Tolstoy à Rhodes, chacune des options proposées par les « prophètes » de l’époque.

Mais allait, et avec quelle mordante ironie, jusqu’à mettre au défi ses contemporains comme ses successeurs que « lorsque le rideau se lève sur cette histoire, quatre-vingts ans après la date actuelle, Londres sera presque exactement comme ce qu’elle est aujourd’hui »…

Introductory Remarks on the Art of Prophecy

THE human race, to which so many of my readers belong, has been playing at children’s games from the beginning, and will probably do it till the end, which is a nuisance for the few people who grow up. And one of the games to which it is most attached is called, « Keep to-morrow dark, » and which is also named (by the rustics in Shropshire, I have no doubt) « Cheat the Prophet. » The players listen very carefully and respectfully to all that the clever men have to say about what is to happen in the next generation. The players then wait until all the clever men are dead, and bury them nicely. They then go and do something else. That is all. For a race of simple tastes, however, it is great fun.

For human beings, being children, have the childish wilfulness and the childish secrecy. And they never have from the beginning of the world done what the wise men have seen to be inevitable. They stoned the false prophets, it is said; but they could have stoned true prophets with a greater and juster enjoyment. Individually, men may present a more or less rational appearance, eating, sleeping, and scheming. But humanity as a whole is changeful, mystical, fickle, delightful. Men are men, but Man is a woman.

But in the beginning of the twentieth century the game of Cheat the Prophet was made far more difficult than it had ever been before. The reason was, that there were so many prophets and so many prophecies, that it was difficult to elude all their ingenuities. When a man did something free and frantic and entirely his own, a horrible thought struck him afterwards; it might have been predicted. Whenever a duke climbed a lamp-post, when a dean got drunk, he could not be really happy, he could not be certain that he was not fulfilling some prophecy. In the beginning of the twentieth century you could not see the ground for clever men. They were so common that a stupid man was quite exceptional, and when they found him, they followed him in crowds down the street and treasured him up and gave him some high post in the State. And all these clever men were at work giving accounts of what would happen in the next age, all quite clear, all quite keen-sighted and ruthless, and all quite different. And it seemed that the good old game of hoodwinking your ancestors could not really be managed this time, because the ancestors neglected meat and sleep and practical politics, so that they might meditate day and night on what their descendants would be likely to do.

But the way the prophets of the twentieth century went to work was this. They took something or other that was certainly going on in their time, and then said that it would go on more and more until something extraordinary happened. And very often they added that in some odd place that extraordinary thing had happened, and that it showed the signs of the times.

Thus, for instance, there were Mr. H. G. Wells and others, who thought that science would take charge of the future; and just as the motor-car was quicker than the coach, so some lovely thing would be quicker than the motorcar; and so on for ever. And there arose from their ashes Dr. Quilp, who said that a man could be sent on his machine so fast round the world that he could keep up a long chatty conversation in some old-world village by saying a word of a sentence each time he came round. And it was said that the experiment had been tried on an apoplectic old major, who was sent round the world so fast that there seemed to be (to the inhabitants of some other star) a continuous band round the earth of white whiskers, red complexion and tweeds…a thing like the ring of Saturn.

Then there was the opposite school. There was Mr. Edward Carpenter, who thought we should in a very short time return to Nature, and live simply and slowly as the animals do. And Edward Carpenter was followed by James Pickie, D.D. (of Pocahontas College), who said that men were immensely improved by grazing, or taking their food slowly and continuously, alter the manner of cows. And he said that he had, with the most encouraging results, turned city men out on all fours in a field covered with veal cutlets. Then Tolstoy and the Humanitarians said that the world was growing more merciful, and therefore no one would ever desire to kill. And Mr. Mick not only became a vegetarian, but at length declared vegetarianism doomed (« shedding, » as he called it finely, « the green blood of the silent animals »), and predicted that men in a better age would live on nothing but salt. And then came the pamphlet from Oregon (where the thing was tried), the pamphlet called « Why should Salt suffer? » and there was more trouble.

And on the other hand, some people were predicting that the lines of kinship would become narrower and sterner. There was Mr. Cecil Rhodes, who thought that the one thing of the future was the British Empire, and that there would be a gulf between those who were of the Empire and those who were not, between the Chinaman in Hong-Kong and the Chinaman outside, between the Spaniard on the Rock of Gibraltar and the Spaniard off it, similar to the gulf between man and the lower animals. And in the same way his impetuous friend, Dr. Zoppi (« the Paul of Anglo-Saxonism »), carried it yet further, and held that, as a result of this view, cannibalism should be held to mean eating a member of the Empire, not eating one of the subject peoples, who should, he said, be killed without needless pain. His horror at the idea of eating a man in British Guiana showed how they misunderstood his stoicism who thought him devoid of feeling. He was, however, in a hard position; as it was said that he had attempted the experiment, and, living in London, had to subsist entirely on Italian organ-grinders. And his end was terrible, for just when he had begun, Sir Paul Swiller read his great paper at the Royal Society, proving that the savages were not only quite right in eating their enemies, but right on moral and hygienic grounds, since it was true that the qualities of the enemy, when eaten, passed into the eater. The notion that the nature of an Italian organ-man was irrevocably growing and burgeoning inside him was almost more than the kindly old professor could bear.

There was Mr. Benjamin Kidd, who said that the growing note of our race would be the care for and knowledge of the future. His idea was developed more powerfully by William Borker, who wrote that passage which every schoolboy knows by heart, about men in future ages weeping by the graves of their descendants, and tourists being shown over the scene of the historic battle which was to take place some centuries afterwards.

And Mr. Stead, too, was prominent, who thought that England would in the twentieth century be united to America; and his young lieutenant, Graham Podge, who included the states of France, Germany, and Russia in the American Union, the State of Russia being abbreviated to Ra.

There was Mr. Sidney Webb, also, who said that the future would see a continuously increasing order and neatness in the life of the people, and his poor friend Fipps, who went mad and ran about the country with an axe, hacking branches off the trees whenever there were not the same number on both sides.

All these clever men were prophesying with every variety of ingenuity what would happen soon, and they all did it in the same way, by taking something they saw ‘going strong,’ as the saying is, and carrying it as far as ever their imagination could stretch. This, they said, was the true and simple way of anticipating the future. « Just as, » said Dr. Pellkins, in a fine passage, « …just as when we see a pig in a litter larger than the other pigs, we know that by an unalterable law of the Inscrutable it will some day be larger than an elephant, just as we know, when we see weeds and dandelions growing more and more thickly in a garden, that they must, in spite of all our efforts, grow taller than the chimney-pots and swallow the house from sight, so we know and reverently acknowledge, that when any power in human politics has shown for any period of time any considerable activity, it will go on until it reaches to the sky. »

And it did certainly appear that the prophets had put the people (engaged in the old game of Cheat the Prophet) in a quite unprecedented difficulty. It seemed really hard to do anything without fulfilling some of their prophecies.

But there was, nevertheless, in the eyes of labourers in the streets, of peasants in the fields, of sailors and children, and especially women, a strange look that kept the wise men in a perfect fever of doubt. They could not fathom the motionless mirth in their eyes. They still had something up their sleeve; they were still playing the game of Cheat the Prophet.

Then the wise men grew like wild things, and swayed hither and thither, crying, « What can it be? What can it be? What will London be like a century hence? Is there anything we have not thought of? Houses upside down…more hygienic, perhaps? Men walking on hands…make feet flexible, don’t you know? Moon… motor-cars… no heads… » And so they swayed and wondered until they died and were buried nicely.

Then the people went and did what they liked. Let me no longer conceal the painful truth. The people had cheated the prophets of the twentieth century. When the curtain goes up on this story, eighty years after the present date, London is almost exactly like what it is now.

Remarques préliminaires sur l’art de la prophétie

L’espèce humaine, à laquelle appartiennent tant de mes lecteurs, a joué depuis le commencement, et continuera de le faire jusqu’à la fin, à des jeux d’enfants, ce qui est bien désagréable pour les quelques personnes qui sont devenues des grandes personnes. L’un de ces jeux favoris s’appelle « laissez le lendemain dans l’ombre », connu également (par les paysans du Shropshire, je n’en doute pas) sous le nom de « démentir le Prophète ». Les joueurs écoutent avec beaucoup de soin et de respect tout ce que les hommes intelligents ont à leur dire sur ce qui se passera à la génération suivante. Puis, les joueurs attendent que tous les hommes intelligents soient morts et ils les enterrent gentiment. Et puis, ils font le contraire de ce que les gens intelligents avaient prévu. Voilà tout. Mais, pour un peuple aux goûts simples, c’est très amusant.

Car les êtres humains, étant des enfants, ont la malice de l’enfant et son mystère. Et jamais depuis le commencement du monde ils n’ont fait ce que les sages ont considéré comme inévitable. Ils lapidaient les faux prophètes, dit-on, mais ils auraient lapidé les vrais prophètes avec plus de joie encore. Individuellement, les hommes peuvent bien offrir une apparence plus ou moins rationnelles, manger, dormir, intriguer. Mais l’humanité dans son ensemble est mystique et frivole. Les hommes sont les hommes, mais l’Homme est une femme.

Mais au début du XXe siècle le jeu de « démentir le Prophète » était devenu beaucoup plus difficile qu’auparavant. La raison en était qu’il y avait tant de prophètes et de prophéties qu’il était difficile d’échapper à toutes leurs ingéniosités. Quelqu’un se livrait-il à un acte parfaitement libre, excentrique et original qu’aussitôt une pensée horrible lui venait: peut-êre cet acte avait-il été prédit. Qu’un duc escaladât un réverbère, qu’un doyen s’enivrât, il ne pouvait pas être vraiment heureux, car il ne pouvait pas être certain qu’il n’accomplissait pas quelque prophétie. Au début du XXe siècle, il y avait tant d’hommes intelligents qu’on n’en pouvait voir le sol. Ils étaient si nombreux et communs qu’un homme stupide était devevu une rare exception, et quand on en trouvait un, des foules le suivaient dans les rues, s’en emparaient comme d’un trésor pour lui confier quelque haute fonction de l’État. Et tous ces gens d’esprit passaient leur temps à rendre compte de ce qui se passerait le siècle d’après et toutes keurs déductions étaient également claires, également pénétrantes, inflexibles, également différentes. Et il semblait bien que le bon vieux jeu de démentir vos ancêtres cette fois fut devenu impossible, parce que les ancêtres oubliaient de manger et de boire et négligeaient la politique courante pour méditer jour et nuit sur ce que leurs descendants seraient susceptibles de faire.

Mais voici comment s’y prenaient les prophètes du XXe siècle. Ils prenaient quelque chose qui se faisait de leur temps et il disaient que cela se ferait de plus en plus jusqu’à ce qu’il en résultât quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Et très souvent, ils ajoutaient que quelque part déjà ce résultat avait été atteint et qu’il portait les marques du temps.

Ainsi, par exemple, il y avait M. HG Wells et d’autres qui prétendaient que la science se chargerait de l’avenir, et tout comme l’automobile est plus rapide que la voiture, de même quelque nouvel appareil serait plus rapide que l’automobile, et ainsi de suite à l’infini. Et de leurs cendres s’éleva M. Quilp, qui disait qu’un homme pourrait être lancé sur sa machine à une telle vitesse autour du globe qu’il pourrait entretenir une conversation animée dans quelque village du vieux monde en ne disant qu’un mot d’une phrase à chaque tour. Et on disait même que l’expérience avait été tentée sur un vieux major au teint apoplectique, qui fut envoyé autour du monde à une telle vitesse qu’il semblait y avoir tout autour (pour les habitants d’autres planètes) une bande continue de favoris blancs, de teint écarlate et de tweed – quelque chose comme l’anneau de Saturne.

Puis il y avait aussi l’école opposée. Il y avait M. Edward Carpenter qui pensait que bientôt nous retournerions à la nature pour vivre simplement et lentement comme les animaux. Et Edward Carpenter fut suivi par James Pickie, DD (du Pocohontas College), qui enseignait que les hommes avaient tout à gagner à brouter ou du moins à prendre leur nourriture lentement et sans interruption à la manière des vaches. Et il disait qu’il avait obtenu les résultats les plus encourageants en persuadant des hommes de la City à prendre leur nourriture à quatre pattes dans un champ couvert de côtelettes de veau. Puis, Tolstoï et les Humanitaires proclamèrent que le monde allait vers plus de bonté et qu’un jour viendrait où plus personne ne voudrait plus tuer. Et M. Mick non seulement se fit végétarien mais condamna le végétarianisme (qui , disait-il excellemment, « verse » le sang vert des animaux silencieux»), et que dans les temps à venir les hommes ne se nourriraient plus que de sel. Et puis vint la brochure de l’Oregon (où la chose a été essayée), qui demandait « Pourquoi le Sel souffrirait-il? » et les difficultés n’étaient pas près de finir.

Et d’autre part, il y avait des personnes qui avaient prédit que les liens de parenté se feraient de plus en plus étroits. M. Cecil Rhodes pensait qu’il n’y avait d’avenir que pour l’Empire britannique, et qu’un fossé de plus en plus profond se creuserait entre ceux qui en seraient et ceux qui n’en seraient pas, entre le Chinois de Hong Kong et le Chinois de l’extérieur, entre l’Espagnol du Rocher de Gibraltar et l’Espagnol du dehors, un abîme tout pareil à celui qui sépare l’homme et les animaux inférieurs. Et de même son fougueux ami, le Dr Zoppi (« le Paul de l’Anglo-Saxonisme »), poussant cette doctrine plus loin encore, proclama que cannibale serait celui qui mangerait un membre de l’Empire, mais qu’on ne serait pas réputé cannibale pour manger de l’un quelconque des peuples soumis, qu’il serait bon pourtant de ne tuer qu’en évitant toute inutile cruauté. L’horreur qu’il éprouvait à l’idée de manger un indigène de la Guyane britannique montrait assez qu’on calomniait son stoïcisme en l’accusant de manquer de coeur. Il était, cependant, dans une position difficile, car on disait qu’il avait tenté l’expérience, et, comme il vivait à Londres, il ne put se nourrir que d’Italiens joueurs d’orgue de Barbarie. Et sa fin fut terrible, car comme il veait de se mettre à ce régime, Sir Paul Swiller fit sa fameuse communication à la Royal Society, où il établissait que non seulement les sauvages avaient raison de manger leurs ennemis, mais qu’ils avaient pour le faire des raisons hygiéniques et morales, les qualités de l’ennemi une fois mangé passant, il est vrai, à celui qui l »avait mangé. L’idée qu’il était en train de devenir un Italien joueur d’orgue était presque plus que ce que le vieux et doux professeur pouvait supporter.

Il y avait M. Benjamin Kidd, qui enseignait que notre espèce se soucierait de plus ne plus de l’avenir. Son idée fut développée plus fortement par William Borker, qui écrit ce page que chaque écolier sait par cœur, sur les hommes qui dans les siècles futurs pleureront sur les tombes de leurs descendants, sur les touristes qui se feront conduire sur le champ de bataille de quelque lutte historique qui devait avoir lieu dans plusieurs siècles.

Et M. Stead, lui aussi, important, qui pensait que l’Angleterre du XXe siècle serait unie aux Etats-Unis d’Amérique, et son jeune lieutenant, Graham Podge, qui y ajoutait la France, l’Allemagne et la Russie, la Russie dont il faisait par abréviation Ra.

Et M. Sidney Webb enfin qui nous assurait que l’avenir serait témoin d’un ordre, d’une propreté sans cesse accrue dans la vie des gens, et son pauvre ami Fipps qui en devint fou et parcourait le pays une hache à la main, abattant les branches des arbres chaque fois qu’elles n’étaient pas en nombre égal des deux côtés.

Tous ces hommes éminents prophétisaient, avec toutes sortes d’ingéniosités différentes, ce qui allait bientôt se passer, et ils s’y prenaient au fond tous de la même manière, puisqu’ils choisissaient chacun quelque courant pour le prolonger aussi loin que le premettait l’imagination. Telle était, selon eux, la manière la plus simple et la plus sûre d’anticiper sur l’avenir. «Tout de même, » écrivait le Dr Pellkins, dans une superbe page, – «tout de même qu’en voyant un porc plus gros que les autres porcs dans une litière, nous savons que, par une loi immuable de l’Inconnaissable, qu’il sera un jour plus gros qu’un éléphant, – tout de même qu’en voyant des herbes et des pissenlits envahir un jardin, nous savons qu’en dépit de tous nos efforts, ils dépasseront les cheminées et recouvriront la maison, de sorte que savons et reconnaissons avec vénération, que si quelque puissance que ce soit s’est montrée active pendant une période donnée dans les affaires humaines, elle continuera à se développer jusqu’à ce qu’elle atteigne le ciel. «

Et il apparut certainement que les prophètes avaient mis le peuple (engagé dans le vieux jeu de démentir le Prophète) dans une difficulté sans précédent. Il semblait vraiment difficile de faire quoi que ce soit sans accomplir une de leurs prophéties.

Mais il y avait, néanmoins, dans les yeux des ouvriers dans la rue, des paysans aux champs, des marins et des enfants et surtout des femmes, une lueur étrange qui faisait que les sages restaient dans le doute et dans la fièvre de l’hésitation. Ils ne pouvaient pas imaginer la joie dans leurs yeux immobiles. Ils cachaient encore quelque chose, ils n’avaient pas cessé de jouer à démentir le Prophète.

Ensuite, les sages devenaient fous, ils déambulaient de ci de là, criant: «Qu’est-ce? Qu’est-ce que cela peut-être? Que sera Londres d’ici cent ans? Y a-t-il quelque chose à quoi nous n’ayons pas pensé? Mettre les maisons- sens dessus dessous, plus hygiéniques, peut-être? Les hommes marchant sur leurs mains – en rendant aux pieds leur flexibilité? La lune? … Les autos? … sans tête? …. » Et c’est ainsi qu’ils déambulaient et divaguaient, puis ils mouraient et on les enterraient gentiment.

Et puis on s’en alllait et les gens faisaient à leur guise. Ne cachons pas plus longtemps la pénible vérité. Le peuple avait démenti les prophètes du XXe siècle. Et au moment où le rideau se lève sur cette histoire, à quatre-vingts ans d’ici, Londres est à bien peu près ce qu’il est aujourd’hui.

Voir aussi:

Why did George Orwell call his novel « Nineteen Eighty-Four »?

David Allen Green

Jack of Kent

Saturday, 28 February 2009

The usual explanation for the choice of title of Nineteen Eighty-Four is that it was a play on the last two digits of 1948, the year the manuscript was finished.

This has never convinced me. I think there may be a better explanation, which comes from George Orwell’s intellectual hostility to the Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton.

This post sets out this alternative explanation as to why Orwell did give his novel the title Nineteen Eighty-Four. It is culled from work I did some time ago when I was considering a higher degree. Although the coincidence on which it is based has been noticed before, I am not aware of any other attempt to assess the alternative explanation that I offer.

A choice of title

In autumn 1948, Orwell is uncertain as to the title of his new novel. He has two titles in mind, and he asks at least two people for their view. In a letter dated 22 October 1948, Orwell explains the dilemma to his literary agent:

“…I have not definitely decided on the title. I am inclined to call it either NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR or THE LAST MAN IN EUROPE, but I might just possibly think of something else in the next week or two.”

On the same day he also writes to his new publisher and makes the same unsure admission:

“…I haven’t definitely fixed on the title but I am hesitating between NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR and THE LAST MAN IN EUROPE.”

However, within a month, the first of these two titles appears to have stuck. At least other people had taken it up. In December 1948, the publisher had compiled a report on the novel, calling it “1984”, as did one of the professional readers.

By 17 January 1949, Orwell himself has clearly made his choice of title and was now discussing whether it should be entitled “1984” or “Nineteen Eighty-Four”.

The book was published later that year.

The conventional explanation

The conventional account is now almost an urban myth. Everybody knows it, so to speak.

This 1948 explanation, although widely adopted, is actually not that well attested. For example, I have not found it stated anywhere by Orwell or by anyone with whom he conversed.

So far, I have only been able to trace the 1948 explanation to an American publisher called Robert Giroux, who saw Nineteen Eighty-Four through the press for the US edition.

However, Orwell was not particularly close to Giroux, and there is no reason to believe that Giroux was privy to any special information about Nineteen Eighty-Four. Although there is some correspondence between Orwell and Giroux, I have not seen any mention in that correspondence of why the book had this title.

In passing, I note that Orwell complained that he did not like what Giroux was doing to the book in the US edition. Nor did he appreciate the unsolicited requests for writing blurbs.

An alternative explanation?

If the 1948 theory is possibly not correct, why did Orwell choose to set his dystopia in the year 1984? My alternative explanation brings us to G.K. Chesterton, an earlier and very different writer to Orwell.

Chesterton was, of course, the writer of the Father Brown stories, as well as a prolific poet and journalist. But it is one of his two famous novels (the other being The Man Who Was Thursday) with which I am concerned here: The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill is a fantasy set in a future London. (As a fantasy writer, Chesterton has the deserved admiration of modern fantasy writers such as Neil Gaiman.) The hero is Auberon Quin, a well-meaning eccentric who suddenly becomes King. The political context for all this is set out when the story begins:

VERY few words are needed to explain why London, a hundred years hence, will be very like it is now, or rather, since I must slip into a prophetic past, why London, when my story opens, was very like it was in those enviable days when I was still alive.

The reason can be stated in one sentence. The people had absolutely lost faith in revolutions. All revolutions are doctrinal…such as the French one, or the one that introduced Christianity.

For it stands to common sense that you cannot upset all existing things, customs, and compromises, unless you believe in something outside them, something positive and divine. Now, England, during this century, lost all belief in this. It believed in a thing called Evolution. And it said, « All theoretic changes have ended in blood and ennui. If w change, we must change slowly and safely, as the animals do. Nature’s revolutions are the only successful ones. There has been no conservative reaction in favour of tails.”

And some things did change. Things that were not much thought of dropped out of sight. Things that had not often happened did not happen at all. Thus, for instance, the actual physical force ruling the country, the soldiers and police, grew smaller and smaller, and at last vanished almost to a point. The people combined could have swept the few policemen away in ten minutes: they did not,because they did not believe it would do them the least good. They had lost faith in revolutions.

Democracy was dead; for no one minded the governing class governing. England was now practically a despotism, but not an hereditary one. Some one in the official class was made King. No one cared how; no one cared who. He was merely an universal secretary.

In this manner it happened that everything in London was very quiet. That vague and somewhat depressed reliance upon things happening as they have always happened, which is with all Londoners a mood, had become an assumed condition. There was really no reason for any man doing anything but the thing he had done the day before.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill is, however, now more famous for its preface, entitled Introductory Remarks on the Art of Prophecy. Only a few hundred words long, it is a much-quoted source of Chestertonian wit. (It begins wonderfully with “THE human race, to which so many of my readers belong…”.)

The preface is not used to introduce the story but to undermine both modernist pretensions and radical predictions. Chesterton ridicules in turn H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter (the early environmentalist), Leo Tolstoy, Cecil Rhodes, Benjamin Kidd ( a sociologist), W. T. Stead (a campaigning journalist), and Sidney Webb. In each instance their views are stated and then juxtaposed with an absurdly exaggerated view of an invented eccentric.

For example:

There was Mr. Sidney Webb, also, who said that the future would see a continuously increasing order and neatness in the life of the people, and his poor friend Fipps, who went mad and ran about the country with an axe, hacking branches off the trees whenever there were not the same number on both sides.

And so on. Chesterton then concludes the preface with a provocative challenge to every other forecaster or prophet. They would err as every such pundit had erred:

All these clever men were prophesying with every variety of ingenuity what would happen soon, and they all did it in the same way, by taking something they saw ‘going strong’, as the saying is, and carrying it as far as ever their imagination could stretch.

So:

When the curtain goes up on this story, eighty years after the present date, London is almost exactly like what it is now.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill was published in 1904; the curtain therefore goes up in 1984.

Orwell and Chesterton

Orwell intellectually loathed GK Chesterton and other Catholic conservative writers.

If this aspect of Orwell’s thought is less appreciated today, it is perhaps because the debates changed. However, Orwell’s criticism of the intellectual and moral dishonesty of Catholic conservatives was a common theme in Orwell’s journalism and other published writing, and he often bracketed Catholic conservatism and his other bugbear, Stalinism.

Indeed, one can often swap his comments on Stalinism and Catholic conservatism. They are almost invariably interchangeable.

Orwell wrote only one major political essay in 1945 (the year he started Nineteen Eighty-Four. This was Notes on Nationalism. This influential essay sets out how certain ideologies (or “nationalisms”) can undermine clear political and moral thinking. And only one writer or politician is examined in this context: Chesterton.

In the essay, Orwell introduces both Chesterton and his long held attitudes towards him:

Ten or twenty years ago, the form of nationalism most corresponding to Communism today was political Catholicism. Its most outstanding exponent – though he was perhaps an extreme case rather than a typical one – was G. K. Chesterton.

Orwell characterises Chesterton:

Chesterton was a master of considerable talent who chose to suppress both his sensibilities and his intellectual honesty in the cause of Roman Catholic propaganda.

And Chesterton’s method:

Every book that he wrote, every paragraph, every sentence, every incident in every story, every scrap of dialogue, had to demonstrate beyond possibility of mistake the superiority of the Catholic over the Protestant or the Pagan.

In a Tribune column in February 1944, Orwell specifically attacked Chesterton’s assertions about change over time:

It is not very difficult to see that this idea is rooted in the fear of progress. If there is nothing new under the sun, if the past in some shape or another always returns, then the future when it comes will be something familiar.

Orwell continues by contrasting Chesterton’s Catholic conservatism with his own democratic socialism:

At any rate what will never come – since it has never come before – is that hated, dreaded thing, a world of free and equal human beings.

Orwell and Catholic conservatism

Orwell’s hostility to Chesterton has to be seen in the context of his disdain for other Catholic conservative writers. In a book review as early as 1932, Orwell is dissing Catholic writers:

Our English Catholic apologists are unrivalled masters of debate, but they are on their guard against saying anything genuinely informative.

Later, a central theme of Orwell’s hostility towards ‘political Catholicism’ was its close relationship with Fascism. In 1944, he notes almost in passing,

Outside its own ranks, the Catholic Church is almost universally regarded as pro-Fascist, both objectively and subjectively.

And in a Tribune column of 1945,

The Catholics who said ‘Don’t offend Franco because it helps Hitler’ had more or less consciously helping Hitler for years beforehand.

Animosity towards ‘Catholic conservatism’ was perhaps most obvious in his weekly Tribune column. Fo example, two favourite straw-dollies were the right-wing, Roman Catholic journalists ‘Timothy Shy’ and

‘Beachcomber’. In 1944, Orwell warned readers that, their general ‘line’ will be familiar to anyone who has read Chesterton and kindred writers. Its essential note is denigration of England and of Protestant countries generally.

And therefore,

It is a mistake to regard these two as comics pure and simple. Every word they write is intended as Catholic propaganda.

In a Tribune column in October 1944, Orwell discussed the writing and broadcasting of C.S. Lewis :

[I was] reading, a week or two ago, Mr C. S. Lewis’s recently-published book, Beyond Personality…The idea, of course, is to persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time. I don’t imagine that the attempt would have much success…but Mr. Lewis’s vogue at this moment, the time allowed to him on the air and the exaggerated praise he has received, are bad symptoms and worth noticing…

A kind of book that has been endemic in England for quite sixty years is the silly-clever religious book, which goes on the principle not of threatening the unbeliever with Hell, but of showing him up as an illogical ass, incapable of clear thought and unaware that everything he says has been says has been refuted before. This school of literature started with W. H. Mallock’s New Republic, which must have been written about 1880, and it has a long line of practitioners – R. H. Benson, Chesterton, Father Knox, ‘Beachcomber’ and others, most of them Catholics, but some, like Dr Cyril Allington and (I suspect) Mr Lewis himself, Anglicans.

The line of attack is always the same. Every heresy has been uttered before (with the implication that it has been refuted before); and theology is only understood by theologians (with the implication that you should leave your thinking to the priests)…

One reason for the extravagant boosting that these people get in the press is that their political affiliations are invariably reactionary. Some of them were frank admirers of Fascism as long as it was safe to be so. That is why I draw attention to Mr C. S. Lewis and his chummy little wireless talks, of which no doubt there will be more. They are not really so unpolitical as they are meant to look

Most relevant for the purpose of connecting Orwell to The Napoleon of Notting Hill is his 1946 book review of The Democrat at the Supper Table, where Orwell forcefully attacks the author’s conservative politics and the sophistry of the novel’s central character:

Without actually imitating Chesterton, Mr. Brogan has obviously been influenced by him, and his central character has a Father Brown-like capacity for getting the better of an argument, and also for surrounding himself with fools and scoundrels whose function is to lead up to his wisecracks.

When a clergyman wrote to complain about the tone of Orwell’s review, the reply elaborated on the initial attack:

Ever since W. H. Mallock’s ‘New Republic’ there has been a continuous stream of what one might call ‘clever Conservative’ books, opposing the current trend without being able to offer any viable programme in its place.

Orwell continued, appearing to have in mind the Preface to The Napoleon of Notting Hill:

If you look back twenty years, you will find people like Ronald Knox, Cyril Alington, Chesterton himself and his many followers, talking as though such things as Socialism, Industrialism, the theory of evolution,

psycho-therapy, universal compulsory education, radio, aeroplanes and what-not could be simply laughed out of existence.

So did Orwell take the year 1984 from The Napoleon of Notting Hill?

Taking the stories as a whole it is not too much of a strain to see Nineteen Eighty-Four as a riposte to The Napoleon of Notting Hill. There are many points of comparison. Both books show that a belief in revolution that appears to have gone wrong, and both focus on the frustrations of a sympathetic central character as he attempts to challenge the prevailing system. Both are utopian/dystopian visions, containing prophecies extrapolated from current trends.

There are also many telling contrasts. The Napoleon of Notting Hill is written from the point of view of a Catholic populist and Nineteen Eighty-Four is by an almost secular social democrat.

It is, in many ways, a plausible explanation.

However, this alternative explanation has gaps.

For example, even though Orwell has a clear disdain for Chesterton and is antipathetic to the prophetic pretensions of Chesterton and other religious conservative writers, there is actually no direct evidence that Orwell either had

read or even possessed The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

One feels he « must have done » as it is one of Chesteron’s three best-known works and probably his most quoted, but one cannot invent convenient evidence. The best I can say is that it difficult to imagine Orwell

committing his attacks in Notes on Nationalism without being aware of Chesterton’s clearest and best known statement against « progress ».

Subject to further research, the final position on the question must be inconclusive though fascinating.

However, the possibility that the title of Nineteen Eighty-Four was derived from The Napoleon of Notting Hill does allows us to explore an often overlooked part of Orwell’s political outlook: the deep hostility of a decent and progressive liberal to the intellectual and moral dishonesty of religious conservatives.

FOOTNOTE

Below is the (rather laboured) conclusion to my original academic draft paper with the same title. So much work went into it, I think it surely deserves the light of day! :-) :

It is demonstrable that a literary preoccupation of Orwell in the mid-1940s becomes G. K. Chesterton, a writer whom he had always found fascinating and repulsive, and also associated writers. The relationship between Orwell and Chesterton has been often overlooked (and is sometimes – bizarrely – completely neglected); and there appears to still be no systematic study of Orwell’s attitudes towards writers, such as Chesterton, that he identified as being on the political Right. During this later period, Orwell’s journalism and private writing demonstrated a deep and informed hostility towards the ‘Catholic conservatism’ of Chesterton and related writers. The failure by scholars to explore the possible significance of Chesterton’s earlier use of that year is only partly because there is no major work on Orwell’s relations with the Right.

It cannot however be conclusively proved that the duplication of the date was deliberate, as Chesterton’s novel is not amongst those known to be possessed or read by Orwell, even during the period of preoccupation with Chesterton’s thinking and prophecies.

On the balance of probability, Orwell at least read the Preface. Orwell often generalises confidently about Chesterton’s (lack of) prophetic prowess and, in a 1944 Tribune column, there is perhaps a near paraphrase of Chesterton’s famous preface to the novel. Moreover, Chesterton is often attacked, criticised, quoted and mentioned in passing, as well as being the main subject of the major 1945 essay.

Chesterton was for Orwell a powerful (if negative) influence. It is therefore arguable that Orwell at least read the famous Preface outlining Chesterton’s prophetic claims. Even if this duplication of date (and setting) was a mere coincidence, it is nonetheless clear that Orwell was preoccupied with the figure of Chesterton as the exemplar of intellectual dishonesty during the conception and writing.

Indeed from around 1944 onwards, a clear theme in Orwell’s writing is the re-emergence of his earlier opposition to the politics of Chesterton and related writers: the very array of attitudes that had helped Orwell towards a form of socialism in the early to mid 1930s.

POSTSCRIPT

References and citations available on request. I acknowedge use of copyrighted material. If such quotations are actually a substantial part of the original works, they are used for the non-commercial purpose of criticism of Orwell and Chesterton’s works. Other exemptions may also apply.

Please contact me at jackofkent [at] gmail.com.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton – Le Napoléon de Notting Hill

Editeur

L’imaginaire Gallimard

Bernard Quiriny

Chronic art

A lire aussi : « Le Nommé jeudi », « La Sagesse du père Brown » (Folio) et « Le Poète et les lunatiques » (L’imaginaire, n°92). Sur le Net : le site très complet des inconditionnels de Chesterton,

sous une devise de circonstance -« a common sense for the world’s uncommon nonsense.

Ses inconditionnels disent de lui qu’il fut le plus grand écrivain du vingtième siècle, sans même prendre la peine de limiter la portée de leur compliment aux seules lettres britanniques : Gilbert Keith Chesterton, ajoutent-ils volontiers, avait une opinion sur tout et l’exprimait mieux que quiconque. L’homme s’en est d’ailleurs donné les moyens : outre trente ans de chroniques hebdomadaires dans l’Illustrated London News et treize dans le Daily News, on lui doit un nombre incalculable de romans, nouvelles, recueils de poèmes, essais, biographies, pamphlets et textes en tous genres, sur tous les tons, dans tous les domaines. De sa production invraisemblablement abondante (existe-t-il seulement une bibliographie complète de son oeuvre ?), on retient souvent les plaisantes aventures du Père Brown, prêtre détective astucieux et personnage principal d’une série de nouvelles particulièrement populaires à l’époque, c’est-à-dire au début du siècle. Cigare soudé aux lèvres et canne à la main, Chesterton aurait, dit-on, composé la meilleure partie de son œuvre dans les halls de gare londoniens, dans l’attente d’un de ces trains qu’il n’a jamais su prendre à temps. Publié en 1904 après un recueil de poèmes et une biographie de Robert Browning, le Napoléon de Notting Hill illustre avec à-propos la fantaisie et le goût de l’absurde de cet encyclopédant excentrique dont les portraits valent presque les livres.

C’est encore un iconoclaste que l’on rencontre en ouvrant ce premier roman burlesque et non-sensique où Chesterton renverse avec méthode les fondements de la civilisation britannique : Auberon Quin fait le pitre dans Westminster Garden en compagnie de quelques amis lorsqu’un couple d’officiers interrompt ses acrobaties pour lui annoncer qu’on vient de le proclamer roi d’Angleterre. L’occasion pour lui d’ériger la déraison en principe de société et de réorganiser le pays au gré de son bon plaisir, avec la loufoquerie et le refus de toute chose sérieuse comme uniques exigences. « L’humour, mes amis, c’est la seule chose sacrée qui nous reste. C’est la seule chose qui vous fasse vraiment peur ». Le roi Auberon bute cependant un jour sur plus dingue que lui : un certain Wayne, prévôt de Notting Hill, se présente à la cour pour lui présenter une bien curieuse requête. L’homme revendique l’indépendance de Pump Street et jure de la conquérir à coups d’épée si besoin est -un peu comme si les commerçants de Montmartre décidaient soudainement de faire sécession et de s’affranchir de la tutelle parisienne. Fantaisie politique à bâtons rompus, ce roman hilarant et débridé donne toute la mesure de l’imagination d’un Chesterton qui n’était alors pas encore l’intellectuel populaire connu d’un bout à l’autre de l’Angleterre et prisé par les universités du monde entier. De cette pochade géopolitique, ses admirateurs n’hésitent pas à soutenir qu’elle inspira Michael Collins dans sa conduite du mouvement pour l’indépendance irlandaise (ils racontent aussi que l’un de ses articles dans l’Illustrated London Weekly poussera Gandhi à se lancer dans la lutte contre la colonisation britannique en Inde). Admiré à plus d’un titre par Kingsley Amis, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Burgess et Graham Greene, Chesterton reste bien, entre H.G. Wells et George Bernard Shaw, l’une des plus grandes figures de la littérature édouardienne. Trente ou quarante pages de ce roman loufoque qui cache sa philosophie hautement subversive sous une intrigue rien moins que crédible en convaincront tout un chacun. « C’est clair, à moins que nous soyons tous fous ».

Écrivain et journaliste

anglais (1874-1936)

Il est impossible de comparer cet écrivain à qui que ce soit. Si comme journaliste, il a signé des milliers d’articles dans les journaux de Londres, ipoésie que le théâtre, le roman, la critique littéraire, la sociologie, l’économique, l’histoire, la philosophie et la religion. Sans oublier ses romans policiers. Cette vaste production repose sur une pensée cohérente et claire, et sur une vision telle que tous les thèmes traités sont liés entre eux. À chaque paragraphe ou presque, surgit un aphorisme qui coupe le souffle, ou un lumineux paradoxe qui laisse le lecteur pantois d’admiration.

Chesterton ne s’est pas contenté de créer des caractères, il a lui-même été un caractère au sens le plus fort du mot. Lorsqu’il apparaissait quelque part, brandissant une canne en forme d’épée, sa silhouette corpulente (300 livres) enveloppée d’une cape, coiffé d’un chapeau bosselé et portant de minuscules lunettes lui tombant sur le bout du nez, sa présence provoquait l’amusement des spectateurs. Ce qui ne l’empêcha pas d’être l’un des hommes les plus aimés de son temps. Même ses adversaires lui vouaient une grande affection. Son humilité, son émerveillement devant la vie, sa bonté gracieuse et sa joie de vivre le mettaient à part non seulement des artistes et des célébrités mais de tout être humain.

Gigantesque par le corps, vaste par l’esprit, Chesterton fut un géant à tous égards. Ce géant, même s’il est encore de nos jours souvent cité, est pourtant méconnu en raison même de son envergure: nous avons sans doute intérêt à nous dissimuler à quel point il avait vu clair lorsqu’il dénonçait l’envahissement de la pensée et de la vie par le matérialisme, le relativisme de la morale, le rejet de la religion, la censure exercée par la presse (par opposition à celle exercée contre la presse), l’enlaidissement des arts, la montée de ces deux maux si liés l’un à l’autre que sont les grandes entreprises et les gouvernements mondiaux avec leurs conséquences: la dépendance à l’égard du revenu et la perte de la libertéindividuelle. Les mots de Chesterton sonnent plus vrais encore de nos jours que lorsqu’ils furent écrits, il y a plus de soixante ans. Et malgré le sérieux des sujets qu’il a traités, il ne manque jamais de le faire avec un humour, un esprit et une gaieté débordante. Ses éclats de rire nous sont plus nécessaires que jamais!

N’est-ce pas de lui-même qu’il parle quand il écrit: « He is a [sane] man who can have tragedy in his heart and comedy in his head. » [L’homme sain est celui qui a un coeur tragique et une tête comique.]

À rapprocher de cet aphorisme espagnol :

« El mundo es una tragedia para los que sienten y una comedia para los que piensan. » [Le monde est une tragédie pour ceux qui sentent et une comédiepour ceux qui pensent.]

Chesterton disait aussi:

« The mad man is the one who has lost everything but his reason. »

[Le fou est celui qui a tout perdu sauf la raison.]

Biographie

«Comme la plupart de ceux qui eurent vingt-cinq ans vers 1895, Chesterton, élevé dans l’incroyance, avait adopté successivement toutes les doctrines de son temps: il avait été, tour à tour, évolutionniste en philosophie, anarchiste en politique, ibsénien en morale. Mais sa vie intellectuelle ne devait pas tarder à s’élargir, à devenir plus vigoureuse. Doué d’une intuition merveilleuse, d’une étonnante jeunesse de regard, il allait bientôt découvrir, dans la riche substance de la réalité, ces accords admirables, ces correspondances mystérieusement apparentées qui nous relient au monde et que ceux qu’il appelle les «vagues esprits modernes» ne savent plus reconnaître. Bien décidé à jeter bas le mur maussade qui cache la splendeur de l’univers créé, Chesterton se fit aussitôt une belle réputation d’anarchiste et de démolisseur.»

HENRI MASSIS, De l’homme

à Dieu. Paris, Nouvelles Éditions Latines, 1959, 480 p.

«Philippe Maxence analyse bien le point de départ de la pensée de Chesterton : « En tombant d’une vision théocentrique à une vision uniquement anthropocentrique, l’homme n’a pas seulement perdu ou faussé sa relation à Dieu. Il n’a pas seulement perdu ou faussé sa perception et sa relation à Dieu. Il n’a pas seulement perdu ou faussé sa perception de l’homme. Il a perdu la compréhension de l’univers. La modernité n’a pas rendu l’homme aveugle. Elle a rendu son regard opaque, embué, flou, morne, voilé. Elle l’a libéré de tout lien. Mais en le libérant, elle l’a emprisonné dans une vision inversée « .

Partant de là, Chesterton sera le trublion de l’intelligentsia anglaise au début du vingtième siècle. Il vitupérera, pourfendra, laminera tout l’orgueil de la philosophie moderne qui nie non seulement toute consistance à la Vérité mais aussi la possibilité de la Vérité. Il constatera avec un amusement attristé que » Plus le temps avance, plus les hommes reculent « , par bégaiements successifs, et que les clercs qui devaient rechercher la Vérité ont conduit le monde sur la voie sans issue du désenchantement. Chesterton n’aura donc comme mission que de » ruer dans les brancards » à l’aide d’une plume acerbe, leste, caustique, emportée, qui défendra sans cesse l’imagination comme reine tout en la refusant comme tyran. Il dira donc adieu au négationnisme moderne qui récuse les sens et l’imagination, atrophiant ainsi l’intelligence et nous rendant orphelin du dessein initial du Créateur.»

Philippe Maxence,

Réenchantement du monde: une introduction à Chesterton, Editions Ad

solem, 2004.

Le distributisme

Dévelopée par Hilaire Belloc et Chesterton, au carrefour de pensées issues du monde rural, de certains socialistes et de la doctrine sociale de l’Eglise catholique, cette théorie est centrée sur l’hypothèse suivante : une société stable et bien ordonnée repose sur une distribution correcte de la propriété. Etant donné que la propriété est la base même de laquelle découlent tous les autres droits (qui ne servent à rien si l’on est trop pauvre ou dépendant pour les exercer), il s’ensuit qu’une société démocratique et ordonnée doit à la fois empêcher la concentration de trop de propriété entre les mains de quelques uns et empêcher la création de larges franges de citoyens pauvres (ou dépendant de l’Etat).

Oeuvres

Oeuvres traduites en français (date de la première parution en langue anglaise)

1903. — La vie de Robert Browning (Robert Browning)

1904. — Le Napoléon de Notting Hill (The Napoleon of Nothing Hill)

1905. — Le club des métiers bizarres (The Club of Queer Trades)

1905. — Hérétiques (Heretics)

1907. — Le nommé Jeudi (The Man who was Thursday)

1908. — Orthodoxie (Orthodoxy)

1911. — L’innocence du Père Brown (The Innocence of Father Brown)

1914. — La clairvoyance du Père Brown (The Wisdom of Father Brown)

1914. — L’auberge volante (The Flying Inn)

1914. — La barbarie de Berlin (The Barbarism of Berlin)

1915. — Les crimes de l’Angleterre (The Crimes of England)

1923. —Saint François d’Assise (Saint Francis of Assisi)

1925. — L’homme éternel(The Everlasting Man)

1926. — L’Église catholique et la conversion (The Catholic Church and Conversion)

1927. —Le retour de Don Quichotte (The Return of Don Quixote)

1927. —Le secret du Père Brown (The Secret of Father Brown)

1929. —Le poète et les lunatiques (The Poet and the Lunatics)

1932. —Chaucer (Chaucer. A Study)

1933. —Saint Thomas d’Aquin (St. Thomas Aquinas)

Oeuvres posthumes

1936. — L’homme à la clef d’or (Autobiography)

Textes en ligne

Antichrist, or the Reunion of Christendom: An Ode

The Ballad of the White Horse

The Battle of Lepanto

By the Babe Unborn

Chesterton Day by Day:

Selections from the Writings in Prose and Verse of G. K. Chesterton, with an Extract for every Day of the Year and for each of the Moveable Feasts

A Christmas Carol

The Club of Queer Trades

For the Creche

Greybeards at Play:

Literature and Art for Old Gentlemen

Heretics

How I Found the Superman

The Innocence of Father

Brown

The Man Who Was Thursday

The Man Who Was

Thursday: A Nightmare

Manalive

A Miscellany of Men

On American Morals

The Oracle of the Dog

Orthodoxy

A Prayer in Darkness

Selected Quotes

Tales of the Long Bow

Utopia of Usurers, and

Other Essas

The Wisdom of Father Brown

G.K. Chesterton

Concordance – « A searchable concordance for Heretics and Orthodoxy »

Documentation

En français

DE TONQUÉDEC, Joseph.

G.K. Chesterton, ses idées et son caractère. Paris, Gabriel

Beauchesne Éditeur, 1920, 116 p.

MASSIS, Henri. De l’homme à Dieu. Paris, Nouvelles Éditions Latines, 1959, 480 p. Coll.

«Itinéraires». Il s’agit d’une série de monographies sur tous les auteurs que Massis a connus et fréquentés: depuis Chesterton jusqu’à Bergson, Maritain, Claudel, Péguy, Thibon (qui signe la préface de ce livre). Le livre de Chesterton Orthodoxie avait été traduit en français et suscité l’attention et l’admiration des intellectuels de cette époque, de Claudel en particulier.

En anglais

BELLOC, Hilaire. The Place of Chesterton in English Literature.

Chesterton, Cecil. G.K.

Chesterton, a Criticism.

FFINCH, Michael. G. K.

Chesterton. London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986.

SCHALL, James V. « »Haloes even in Hell »: Chesterton’s Own Private « Heresy »».

New Blackfriars, vol. 84, no 988, juin 2003, pp. 281-292.

WARD, Maisie. Gilbert

Keith Chesterton. New York, Sheed and Ward, 1943.

Textes en ligne

Chesterton and Anti-Semitism, par Ian Boyd C.S.B., S. Caldecott et A. Mackey,G.K.

Chesterton Institute

On the Place of Gilbert Chesterton in English Letters, par Hilaire Belloc. [full entry]

The Essential Chesterton, par David W. Fagerberg, First Things, mars 2000, p. 23-26

The Case of the Forgotten Detectives: The Unknown Crime Fiction of G.K. Chesterton,

par John C. Tibbetts

Chesterton Reformed: A Protestant Interpretation, par James Sauer

Voir enfin:

REMARQUES PRÉLIMINAIRES SUR L’IMPORTANCE DE L’ORTHODOXIE

Rien ne trahit plus singulièrement un mal profond et sourd de la Société moderne, que l’emploi extraordinaire que l’on fait aujourd’hui du mot « orthodoxe ». Jadis l’hérétique se flattait de n’être pas hérétique. C’étaient les royaumes de la terre, la police et les juges qui étaient hérétiques. Lui il était orthodoxe. Il ne se glorifiait pas de s’être révolté contre eux ; c’était eux qui s’étaient révoltés contre lui.

Les armées avec leur sécurité cruelle, les rois aux visages effrontés, l’État aux procédés pompeux, la Loi aux procédés raisonnables, tous comme des moutons s’étaient égarés. L’hérétique était fier d’être orthodoxe, fier d’être dans le vrai. Seul dans un désert affreux, il était plus qu’un homme : il était une Église. Il était le centre de l’univers ; les astres gravitaient autour de lui. Toutes les tortures arrachées aux enfers oubliés n’auraient pu lui faire admettre qu il était hérétique. Or il a suffit de quelques phrases modernes pour l’en faire tirer vanité. Il dit avec un sourire satisfait : « Je crois bien que je suis hérétique », et il regarde autour de lui pour recueillir les applaudissements. Non seulement le mot « hérésie » ne signifie plus être dans l’erreur, il signifie, en fait, être clairvoyant et courageux. Non seulement le mot « orthodoxie » ne signifie plus qu’on est dans le vrai ; il signifie qu’on est dans l’erreur. Tout cela ne peut

vouloir dire qu’une chose, une seule : c’est que l’on ne s’inquiète plus autant de savoir si l’on est philosophiquement dans la vérité. Car il est bien évident qu’un homme devrait se déclarer fou plutôt que de se déclarer hérétique. Le bohème, avec sa cravate rouge, devrait se piquer d’orthodoxie. Le dynamiteur, lorsqu’il dépose une bombe, devrait sentir que, quoi qu’il puisse être par ailleurs, il est du moins orthodoxe.

Il est absurde, en général, pour un philosophe, d’en brûler un autre sur le marché de Smithfield parce qu’ils ne s’accordent pas sur la théorie cosmique. Cela se fit très fréquemment pendant la décadence du moyen âge, sans jamais atteindre son objet. Mais il est une chose infiniment plus absurde et bien moins pratique que de brûler un homme pour sa philosophie, c’est l’habitude de dire que sa philosophie n’a pas d’importance. C’est là une habitude universelle au vingtième siècle, c’est-à-dire pendant la décadence de la grande période révolutionnaire.

Les théories générales sont partout méprisées ; la doctrine des Droits de l’Homme est répudiée, d même que celle de la Chute de l’Homme. L’athéisme lui-même est trop théologique pour nous ; la révolution ressemble trop à un système et la liberté à une contrainte. Nous ne voulons pas de généralisations. M. Bernard Shaw a exprimé cette opinion dans une épigramme parfaite : « La règle d’or, c’est qu’il n’y a pas de règle d’or. » Nous sommes de plus en plus disposés à discuter des détails en

art, en politique et en littérature. Les opinions d’un homme sur les tramways nous importent, ses idées sur Botticelli nous importent. Sur l’ensemble des choses, ses opinions ne nous importent pas. Il peut aborder et explorer un million de sujets, mais il ne doit pas toucher à cet objet étrange : l’univers, car, s’il le faisait, il aurait une religion, il serait perdu. Tout importe, excepté Tout. Il est à peine nécessaire de citer des exemples de la légèreté absolue avec laquelle on traite la philosophie cosmique. Il n’en est pas besoin pour démontrer que, quelle que soit la chose que nous croyons susceptible d’influencer les affaires pratiques, nous ne pensons jamais qu’il importe qu’un homme soit pessimiste ou optimiste, cartésien ou hégélien, matérialiste ou spiritualiste. Laissez-moi cependant prendre un exemple au hasard.

Autour de la plus innocente table à thé nous entendons dire couramment que « la vie ne vaut pas d’être vécue ». Nous écoutons émettre cette opinion comme si on disait que la journée est belle. Personne ne songe que cela puisse avoir le moindre effet sur les hommes ou sur le monde. Et pourtant, si cette parole était réellement crue, le monde se trouverait renversé. Les meurtriers se verraient attribuer des médailles pour avoir sauvé des hommes de la vie ; les pompiers seraient dénoncés pour avoir arraché des hommes à la mort ; les poisons remplaceraient les remèdes ; les médecins seraient appelés auprès des personnes bien portantes et la Royal

Humane Society serait exterminée comme une horde d’assassins.

Cependant nous ne nous demandons jamais si le causeur pessimiste fortifie ou désorganise la Société, parce que nous sommes convaincus que les théories sont sans importance.

Ce n’était certes pas l’idée des initiateurs de notre liberté. Quand les vieux libéraux

arrachèrent le bâillon à toutes les hérésies, leur idée était de faciliter les découvertes religieuses et philosophiques. La vérité cosmique leur paraissait si importante, que chacun était mis en demeure d’apporter un témoignage indépendant. L’idée moderne est que la vérité cosmique est si dénuée d’intérêt que tout ce qu’on en peut dire est sans valeur. Les premiers libérèrent la recherche comme on lâche un beau dogue, les derniers comme on rejette à la mer un poisson qui ne vaut pas la peine d’être mangé. Jamais les discussions sur la nature de l’homme ne furent aussi rares qu’à présent, alors que, pour la première fois, tout le monde peut en discuter. La restriction ancienne signifiait que les orthodoxes seuls étaient admis à discuter de la religion. La liberté moderne signifie que plus personne n’est autorisé à en discuter. Le bon goût, la dernière et la plus vile des superstitions humaines, a réussi à nous imposer le silence, là où tout le reste avait échoué.

Il y a soixante ans, il était de mauvais goût d’être un athée avoué. Alors apparurent

les disciples de Bradlaugh, les derniers croyants, les derniers qui aimèrent Dieu, mais ils n’y purent rien changer. Il est toujours de mauvais goût d’être un athée,

néanmoins leurs souffrances ont gagné ceci : c’est qu’aujourd’hui il est d’aussi mauvais goût d’être un fervent chrétien.

L’émancipation n’a fait qu’ enfermer le saint dans la même tour de silence que l’hérésiarque. Et nous parlons de lord Anglesey, du beau temps, et nous appelons cela l’entière liberté de toutes les croyances. Il est cependant des gens qui pensent, et moi-même, que ce qu’il y a de plus important chez un homme, c’est tout de même sa conception de l’univers. Nous pensons qu’il est très important pour un propriétaire de connaître les revenus de son locataire, mais plus important encore de connaître sa philosophie. Nous pensons que, pour un général qui se prépare à combattre un ennemi, il est important de connaître les effectifs de l’ennemi, mais plus important encore de connaître sa philosophie. Nous pensons que la question n’est pas de savoir si la théorie cosmique influe sur les choses, mais si, dans le cours des temps, il est rien d’autre qui influe sur elles. Au quinzième siècle, on mettait un homme à la question parce qu’il prêchait une doctrine immorale ; au dix-neuvième siècle, nous avons fêté et adulé Oscar Wilde parce qu’il prêchait une doctrine semblable, et puis nous lui avons brisé le cœur aux travaux forcés parce qu’il la mettait en pratique. On peut se demander laquelle des deux méthodes était la plus cruelle, mais il ne peut y avoir de doute sur celle qui est la plus ridicule. Du moins

l’époque de l’Inquisition ne connut-elle pas la disgrâce d’avoir produit une Société susceptible de faire d’un homme une idole lorsqu’il enseigne les doctrines qui font du même homme un forçat dès qu’il les met en pratique.

Aujourd’hui, la philosophie et la religion, c’est-à-dire notre doctrine des causes finales, ont été bannies presque simultanément des deux sphères où s’exerçait leur influence. Les idées générales dominaient la littérature, elles ont été exclues au cri de « l’art pour l’art ». Les idées générales dominaient la politique, elles ont été rejetées au cri d’« efficacité », ce qui peut se traduire, à peu près, par « la politique pour la politique ».

D’une façon continue, pendant ces vingt dernières années, les idées d’ordre et de liberté se sont effacées de nos livres, les soucis d’esprit et d’éloquence ont disparu de nos parlements. La littérature est devenue volontairement moins politique, la politique moins littéraire. Les théories générales sur les relations des choses se sont ainsi trouvées exclues de toutes deux et nous pouvons nous demander : Avons-nous gagné ou perdu à cette exclusion ? La littérature et la politique sont-elles meilleures pour avoir écarté le moraliste et le philosophe ?

Quand tout s’affaiblit et se ralentit dans la vie d’un peuple, il commence à parler

d’efficacité. Il en va de même de l’homme lorsqu’il sent son corps délabré, il commence alors pour la première fois à parler de santé. Les organismes vigoureux ne parlent pas de leurs fonctions, mais de leurs fins. Un homme ne saurait donner de meilleure preuve de son efficacité physique que lorsqu’il parle gaiement d’aller au bout du monde. Et il ne peut y avoir de meilleure preuve de l’efficacité matérielle d’une nation que lorsqu’elle parle constamment d’un voyage au bout du monde, d’un voyage au Jugement dernier, à la Nouvelle Jérusalem. Il ne peut y avoir de signe plus sûr d’une santé morale robuste que la recherche des idéaux romanesques, c’est dans la première ardeur de l’enfance que nous pleurons pour avoir la lune. Aucun des hommes forts des âges forts n’eût compris ce que nous entendons par « résultat pratique ». Hildebrand nous eût dit qu’il ne travaillait pas pour l’efficacité, mais pour l’Église Catholique ; Danton, qu’il travaillait non pour

l’efficacité, mais pour la liberté, l’égalité et la fraternité. Quand bien même l’idéal de ces hommes eût été simplement d’en jeter un autre du haut de l’escalier, ils songeaient au but, comme des hommes, non aux procédés, comme des paralytiques. Ils ne disaient pas : « En levant efficacement la jambe droite, en me servant, vous pourrez le remarquer, des muscles de la cuisse et du jarret, qui sont en excellent état, je… » Leur sentiment était tout différent. Ils étaient si pénétrés de la belle vision d’un homme étendu au pied de l’escalier que, dans leur extase, l’action suivait comme l’éclair. Dans la pratique, l’habitude de généraliser et d’idéaliser ne signifiait, en aucune manière, la faiblesse. L’âge des grandes théories fut celui des grands résultats. L’ère du sentiment et du beau parler, à la fin du dix-huitième siècle, fut celle d’hommes vraiment robustes et efficaces. Les sentimentalistes vainquirent Napoléon.

Les cyniques ne réussirent pas à capturer De Wet. Il y a un siècle, nos affaires, pour le bien ou pour le mal, furent triomphalement menées par les rhétoriciens. Aujourd’hui, elles sont déplorablement brouillées par des hommes forts et silencieux. Et de même que cette répudiation des grands mots et des grandes visions a produit une race de petits hommes dans la politique, elle a produit une race de petits hommes dans les arts.

Nos politiciens modernes réclament la licence colossale de César et du Surhomme, prétendent qu’ils sont trop pratiques pour être intègres et trop patriotes pour être moraux, mais la conclusion de tout cela, c’est qu’une médiocrité est Chancelier de l’Échiquier. Nos nouveaux philosophes esthétiques réclament la même licence morale, une liberté qui permette à leur énergie de renverser le ciel et la terre et, la conclusion, c’est qu’une médiocrité est Poète Lauréat. Je ne dis pas qu’il n’y ait pas d’hommes plus forts que ceux-là, mais se trouvera-t-il quelqu’un pour prétendre qu’il y eut des hommes plus forts que les Anciens qui étaient dominés par leur philosophie et imprégnés de leur religion ? Que l’asservissement soit supérieur à la liberté, cela peut se discuter, mais que leur asservissement fût plus fécond que notre liberté, nul ne saurait le nier.

La théorie de l’amoralité de l’art s’est fermement établie dans les milieux purement artistiques. Les artistes sont libres de produire ce qu’ils veulent ; ils sont libres d’écrire un Paradis Perdu dans lequel Satan aurait vaincu Dieu ; ils sont libres d’écrire une Divine Comédie dans laquelle le Ciel serait situé au-dessous de l’Enfer. Et qu’ont-ils fait ? Ont-ils produit dans leur universalité rien de plus grand et de plus beau que les paroles proférées par le farouche catholique gibelin ou par l’austère maître d’école puritain ?

Nous savons qu’ils n’ont produit quelques rondels. Milton ne les surpasse pas seulement par sa piété, il les surpasse jusque leur irrévérence. Dans toutes leurs petites plaquettes, vous ne trouverez pas de plus beau défi à Dieu que celui de Satan. Vous n’y trouverez pas non plus un sentiment de la grandeur du paganisme pareil à celui qu’éprouvait ce fervent chrétien qui décrivit Faranata relevantla tête comme s’il méprisait l’enfer. Et la raison en est bien évidente : le blasphème est en effet artistique, parce que le blasphème dépend d’une conviction philosophique. Le blasphème dépend de la croyance et disparaît avec elle. Si quelqu’un pouvait en douter, qu’il se mette sérieusement au travail, et qu’il essaie de trouver des idées blasphématoires contre Thor. Je crois bien que sa famille le retrouvera au bout de la journée dans un état voisin de l’épuisement.

Il s’ensuit donc que, ni dans le monde de la politique ni dans celui de la littérature, le rejet des théories générales n’a été un succès. Il se peut que beaucoup d’idéaux erronés et insensés aient de temps à autre troublé l’humanité, mais, assurément, il n’y a pas eu d’idéal qui dans l’application ait été aussi insensé et aussi erroné que l’idéal pratique. Il n’est rien qui ait manqué tant de bonnes occasions que l’opportunisme de lord Rosebery. Il est vraiment le symbole vivant de son époque : l’homme qui théoriquement est un homme pratique, et, dans la pratique, moins

pratique que n’importe quel théoricien. Dans tout l’univers, il n’est rien de moins sage que cette espèce de culte de la sagesse.

L’homme qui se demande perpétuellement si telle ou telle race est forte, si telle ou telle cause promet bien, est celui qui ne croira jamais assez longtemps à quoi que ce soit pour en assurer la réussite.

Le politicien opportuniste ressemble à un homme qui abandonnerait le billard parce qu’il a été battu au billard, ou le golf parce qu’il a été battu au golf. Il n’est rien de plus nuisible à la réalisation des projets que cette importance démesurée que l’on attache à la victoire immédiate. Rien n’échoue comme le succès. Après avoir découvert que l’opportunisme échouait j’ai été amené à le considérer d’une façon plus générale et en conséquence à voir qu’il doit échouer. Je m’aperçois qu’il est beaucoup plus pratique de commencer par le commencement et de discuter les

théories. Je vois que les hommes qui s’entretuèrent pour l’orthodoxie de la Consubstantialité étaient beaucoup plus sensés que ceux qui se disputent à propos de la loi sur l’Enseignement.

Car les dogmatistes chrétiens, afin d’établir le règne de la sainteté, essayaient tout d’abord de définir ce qui était réellement saint. Nos théoriciens modernes essaient d’instituer la liberté religieuse sans se soucier d’établir ce qu’est la religion et ce qu’est la liberté. Si les prêtres d’autrefois imposaient une opinion aux humains, tout au moins avaient-ils pris quelque peine pour la rendre lucide. Il a été laissé aux foules modernes des anglicans et des non-conformistes de persécuter au nom d’une doctrine qu’elles n’ont pas même énoncée.

Pour ces raisons et pour beaucoup d’autres, moi, du moins, j’en suis arrivé à croire à la nécessité de retourner aux fondements. Telle est l’idée générale de ce livre. Je désire m’y entretenir des plus distingués de mes contemporains, non pas à un point de vue personnel ou simplement littéraire, mais par rapport aux doctrines qu’ils enseignent. Je ne m’occupe pas de M. Rudyard Kipling comme d’un grand artiste ou d’une personnalité vigoureuse, je m’intéresse à lui en tant qu’hérétique, c’est-à-dire en tant que son opinion sur les choses a la hardiesse de différer de la mienne. Je ne m’intéresse pas à M. Bernard Shaw comme à l’un des hommes les plus brillants et les plus honnêtes qui soient, je m’intéresse à lui comme à un hérétique

dont la philosophie est parfaitement solide, parfaitement cohérente, et parfaitement fausse. J’en reviens aux méthodes doctrinales du treizième siècle, dans l’espoir d’aboutir à quelque chose.

Supposons qu’un grand mouvement se produise dans la rue à propos de n’importe quoi, disons, par exemple, d’un réverbère que plusieurs personnes influentes désirent voir démolir. Un moine, vêtu de gris, qui représente l’esprit du moyen âge, est consulté sur la question et commence par dire, dans la forme aride des scolastiques : « Considérons tout d’abord, mes Frères, la valeur de la lumière. Si, prise en soi, la lumière est bonne… » A ce moment il est culbuté, ce qui est presque excusable. Tous les hommes présents se précipitent sur le réverbère qui se trouve démoli en l’espace de dix minutes, et ils s’en vont se congratulant mutuellement de leur sens pratique si peu médiéval. Mais du train où elles vont, les choses ne se règlent pas aussi facilement.

Parmi les démolisseurs du réverbère, les uns ont agi parce qu’ils désiraient la lumière électrique, d’autres parce qu’ils désiraient du vieux fer, d’autres encore parce qu’ils désiraient l’obscurité propice à leurs actes répréhensibles. D’aucuns

trouvaient qu’un réverbère ne suffisait pas, d’autres qu’il était de trop, certains avaient été guidés par le désir de démolir le matériel municipal, d’autres par le désir de détruire quelque chose. Et l’on se bat dans la nuit, sans que personne sache qui il frappe.

Ainsi graduellement et inévitablement, aujourd’hui, demain ou le jour qui suivra, la conviction nou viendra que le moine avait raison après tout, et que tout dépend de la philosophie de la lumière. Seulement, ce dont nous pouvions discuter sous le réverbère, nous devons maintenant en discuter dans les ténèbres.